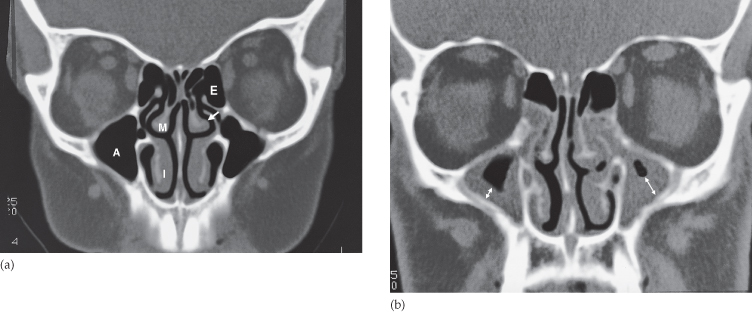

Fig. 16.2 Coronal CT scan. (a) Normal sinuses. Note the excellent demonstration of the bony margins. The arrow points to the middle meatus into which the maxillary antrum and frontal, anterior and middle ethmoid sinuses drain. The region where all these sinuses drain is known as the osteomeatal complex. A, maxillary antrum; E, ethmoid sinus; I, inferior turbinate; M, middle turbinate. (b) Sinusitis. Mucosal thickening prevents drainage of the sinuses. Both antra are almost opaque. The arrows indicate mucosal thickening in the antra.

Allergy and infection both cause mucosal thickening and it is often impossible to say radiologically which condition is responsible. Such changes are often seen in asymptomatic people.

Acute sinusitis is usually diagnosed and treated clinically, but CT is recommended if symptoms persist. Both CT and MRI can elegantly demonstrate mucosal thickening and fluid levels as well as displaying the bony walls of the sinuses. Sinus anatomy is ideally demonstrated with multiplanar reformatted CT in order to assess the drainage sites of the frontal, ethmoid and maxillary sinuses and is a great aid for the surgeon planning endoscopic sinus surgery (Fig. 16.2).

Opaque Sinus

The sinus becomes opaque when all the air is replaced. The causes of an opaque sinus (Box 16.1) are:

- Infection or allergy. The air in the sinus is replaced by fluid, or a grossly thickened mucosa, or a combination of the two.

- Mucocele. Mucoceles are obstructed sinuses. Secretions accumulate and the sinus becomes expanded. A frontal sinus mucocele may erode the roof of the orbit and cause exophthalmos. CT clearly shows the size and extent of a mucocele.

- Antrochoanal polyp. These typically arise from the maxillary antrum mucosa and prolapse through an ostium in the medial antral wall into the nasal cavity and sometimes back into the nasopharynx. This results in unilateral opacification of the maxillary antrum and the frontal and anterior ethmoid sinuses due to obstruction of their drainage pathways.

- Trauma. A fracture of the sinus wall may result in haemorrhage and opacification of the sinus.

- Carcinoma of the sinus or nasal cavity. In all opaque sinuses, particularly the antra, special attention should be paid to the bony margins on CT, because if these are destroyed a diagnosis of carcinoma needs exclusion (Fig. 16.3). CT is superb at visualizing bone destruction, but MRI is preferred for demonstrating tumour invasion by showing the extent of any soft tissue mass beyond the sinus cavity. Both CT and MRI have an important role in treatment planning and in assessing response to treatment.

- Infection

- Allergy

- Mucocele

- Antrochoanal polyp

- Trauma with haemorrhage

- Carcinoma of the sinus or nasal cavity

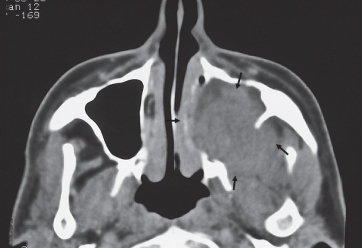

Fig. 16.3 Carcinoma of the antrum. CT scan showing a large mass arising from the left antrum destroying its bony walls and extending into the adjacent soft tissues. The arrows point to the extent of the tumour. The opposite antrum is normal.

Nasopharynx

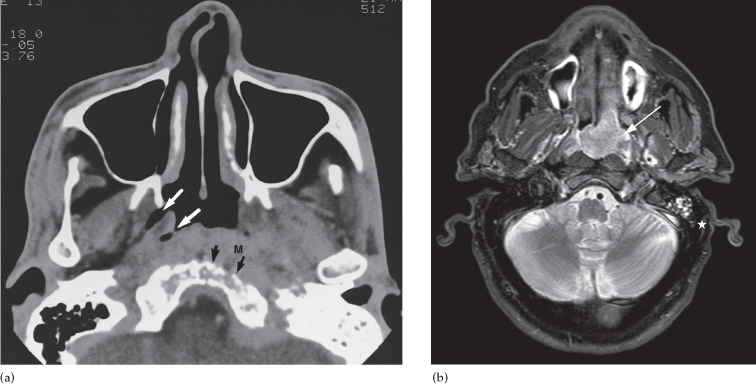

Computed tomography and especially MRI give excellent visualization of the nasopharynx and can demonstrate the presence of tumour as a mass disrupting the symmetry of the nasopharynx. The most common type of tumour is nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Fig. 16.4), a type of squamous cell carcinoma that usually presents late with local invasion and necrotic lymph node metastases. Imaging is required to detect spread into the skull base, perineural extension and lymphadenopathy in the neck (see Fig. 16.13).

Fig. 16.4 Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. (a) CT scan showing a mass (M) in the nasopharynx on the left extending into the soft tissues of the postnasal space and eroding the skull base (black arrows). Note how the tumour obliterates the fossa of Rosenmuller and eustachian recess, which are shown on the normal right side (white arrows). (b) MRI scan in another patient clearly showing the extent of the tumour (arrow). The tumour is blocking the left eustachian tube and fluid is accumulating in the mastoid (*).

Orbits

Computed tomography and MRI clearly demonstrate the anatomy of the orbits. Imaging is indicated in all patients with exophthalmos because it is important to distinguish between masses arising within the orbit, masses arising outside the orbit and thyroid eye disease. With an intra-orbital mass, its relationship to the optic nerve can be determined.

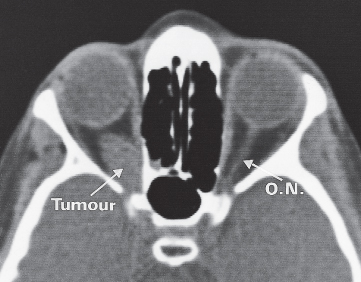

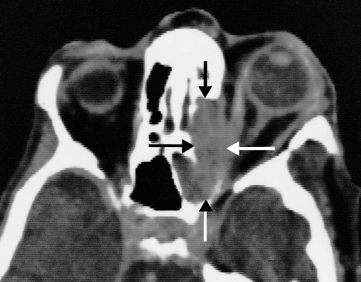

The main causes of intra-orbital masses include various tumours, such as lymphoma and optic nerve tumours (Fig. 16.5), and vascular malformations. The most common orbital masses originating outside the orbit, which often present with exophthalmos, are infection secondary to sinusitis, mucoceles of the frontal or ethmoid sinuses, tumours (Fig. 16.6) and a meningioma arising from the sphenoid ridge.

Fig. 16.5 Optic nerve glioma. CT scan showing a soft tissue mass arising from the optic nerve (O.N.). The opposite orbit demonstrates the normal anatomy.

Fig. 16.6 Carcinoma of the ethmoid sinus invading the orbit and causing proptosis. The tumour is arrowed.

In thyroid eye disease, there is enlargement of the extraocular muscles (Fig. 16.7) which is frequently bilateral and may affect one, several or all the eye muscles. There is also hypertrophy and oedema of the fat behind the eye which adds to the exophthalmos. When severe, these changes can lead to compression of the optic nerve in the apex of the orbit.