CHAPTER 29 Overview of Adult Primary Neoplasms and Metastatic Disease

The overwhelming majority of intracranial neoplasms are metastatic to the central nervous system (CNS). In a 2005 article, Nathoo, Chalavi, Barnett, and Toms wrote: “The incidence of metastases to the brain is estimated to be about 170,000/year in the USA, an incidence 10 times higher than that of primary malignant brain tumors.”1 However, the source that they quote in their review article, as the reference for this information, does not even mention the words “metastasis,” “metastases,” or “metastatic.”1–3

Another article that is commonly quoted is a 2005 review by Gavrilovic and Posner, who wrote: “Thus, from epidemiologic studies, the incidence of brain metastases seems equal to or no more than twice that of gliomas. These data almost certainly underestimate the true incidence of brain metastases because some metastases are asymptomatic.”4

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Gavrilovic and Posner reviewed metastatic disease and reported that metastases are up to 10 times more common than primary brain tumors.4 Nathoo and associates estimated an incidence of 170,000 patients with metastatic disease per year.5 However, the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) reported, in 2010, that the incidence of primary brain tumors is 18.71 cases/100,000/yr (7.19 malignant and 11.52 nonmalignant). This report predicts 62,930 new primary brain tumors occurring in the United States during 2010.6 This would calculate to a primary to secondary tumor ratio of 3:5—certainly more metastasis, almost twice, but not overwhelmingly more, and obviously not a factor of 10.

The Swedish epidemiology study of hospital admissions showed a doubling of brain metastasis from 7 to 14/100,000 during the 2 decades from 1987 to 2006.7 Again, compared with the CBTRUS data, this would be a primary to secondary ratio (at present) of 14/18.71, with primary tumors being more common. However, this is not a fair comparison, because the data come from two different populations: Sweden and the United States.

Materljan and colleagues reported a small population-based study (from Croatia) of 175 CNS tumors, showing primary neoplasms to be more common (11.8/100,000/yr) than metastases (9.9/100,000/yr).8 Another population-based study from Croatia showed that 88% of intracranial tumors were primary, with an incidence rate of primary tumors of 11.8/100,000/yr.9

A study of asymptomatic human subject volunteers provides yet another potential surveillance mechanism. In several large studies, including a meta-analysis of 16 projects with 19,559 subjects studied, the prevalence of unsuspected primary brain tumors was 0.7% (135 patients) but there were no cases of metastatic disease.10 In a recent population-based study from Rotterdam, 2000 adults (aged 45 to 96 years, mean 63 years) were scanned with high-quality MRI at 1.5 Tesla.11 There was one incidental metastasis, 1 incidental malignant primary brain tumor, and 31 (1.6%) incidental primary benign tumors (18 meningioma, 4 schwannoma, 6 pituitary adenoma). If we were to use this study, we could “prove” that primary tumors are 32 times more common than metastatic disease! So, if metastatic deposits are symptomatic, we find them when evaluating the symptoms. If a patient has certain cancers, we find the lesions with a staging examination. If the patient is asymptomatic, we will not find the metastasis, and the prevalence of these asymptomatic metastatic lesions is probably very low, unlike the prevalence of asymptomatic primary tumors.

CASCADE THEORY

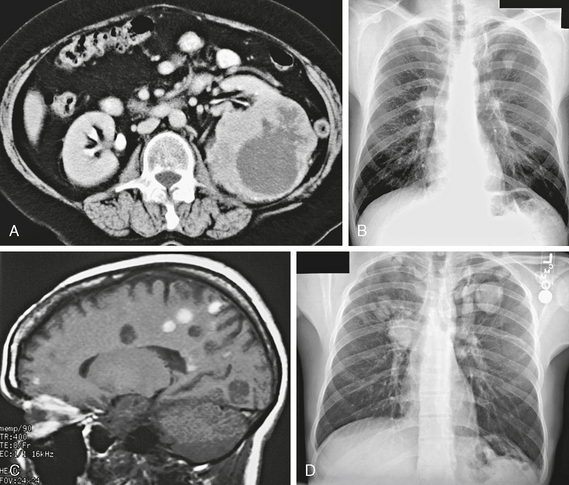

How do extraneural malignancies reach the CNS? The “cascade theory” describes the sequence of events required for parenchymal CNS metastasis. Viable tumor cells must enter the systemic circulation to reach the brain. For example, a testicular tumor can spread into the venous system as well as the lymphatics. The sequence begins with passage of cells into the perinephric and para-aortic area—the normal venous and lymphatic drainage for the testis. From there, tumor cells travel through the inferior vena cava or the lymphatic drainage to the thoracic duct and then pass through the right side of the heart into the pulmonary circulation. The capillary bed in the lung will “trap” the tumor cells. However, some may become locally invasive in the lung (a lung metastasis) and then travel through the pulmonary veins into the left side of the heart and then enter the systemic circulation. Alternately, tumor cells may bypass the “filtration bed” of the lung, through a right-to-left shunt or a patent foramen ovale. For gastrointestinal primary neoplasms, the sequence is one step more complicated. The portal venous blood drains into the liver, which is also a “filtration bed.”1 The case of renal cell carcinoma in Figure 29-1 shows a typical course of disease progression from primary tumor to lung to brain.

FIGURE 29-1 A, Contrast-enhanced axial CT image shows a large irregular mass in the left kidney, which is the primary renal cell carcinoma (RCC). B, Frontal posteroanterior radiograph. There is an irregular left upper lobe mass, which is a pulmonary metastasis from the RCC. C, Sagittal T1W MR image. Many of the multiple small nodular lesions show T1 shortening from blood products. These are hemorrhagic metastases. D, Frontal posteroanterior radiograph. Follow-up study shows progression of the lung metastases with growth and newly visible lesions.

RATE, DELAY, SURVIVAL

Metastatic disease from non–small cell lung cancer and breast cancer occurs in 8% to 20% of patients. Metastases from lung cancer tend to occur earlier, with a median of 3 months, whereas breast cancer metastasis is found at a median of 42 months.7 After the first hospitalization for brain metastasis, the median survival is only 3 months, and only 13% of patients will survive for a year.7

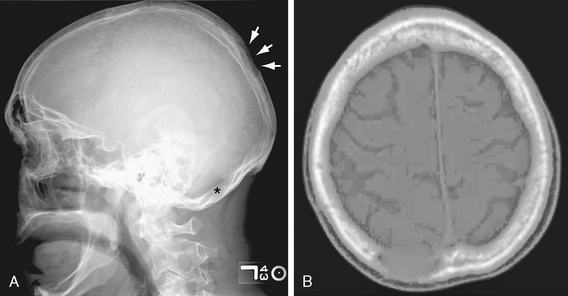

SCALP AND SKULL

Primary tumors of the skull vault are uncommon and include hemangioma, osteoma, Paget disease of bone, and fibrous dysplasia. Calvarial metastasis, as in other bones, may be lytic (e.g., Langerhans’ histiocytosis, breast, lung) or blastic (e.g., breast, prostate, lymphoma, pancreas, carcinoid). Metastatic lesions to bone do not create or destroy bone directly. Instead, the metastasis may stimulate osteoclastic reabsorption, producing lytic lesions; or, there may be a desmoplastic tissue reaction in the bone, creating a dense “blastic” metastasis. Skull metastasis may be symptomatic or can produce painless swelling or deformity (Fig. 29-2).

FIGURE 29-2 A, Lateral skull radiograph. There are two lytic lesions: one is in the parietal region (arrows) and a second lesion is barely visible in the occipital bone (asterisk). B, Axial CT image. The parietal lytic lesion is just to the right of midline.

In the skull base, primary tumors may arise from the nerves (schwannoma, neurofibroma) meninges (meningioma, hemangiopericytoma), pituitary gland (invasive adenoma), or the paranasal sinuses (inverting papilloma, squamous cell carcinoma, esthesioneuroblastoma). Clival neoplasms are only uncommonly metastatic, especially when that is the only bone involved, accounting for only 15% of cases.12 Chordomas are the most common primary tumors of the clivus and probably the most common neoplasm overall in this bone. Primary chondrosarcomas arise most often from the synchondroses (e.g., the foramen lacerum region).

EXTRA-AXIAL METASTASIS

Dural metastases are found in almost 10% of patients dying with cancer.13 In some cases, only dural metastases are present and they may mimic meningioma, hemangiopericytoma, or solitary fibrous tumor.14 In men, dural metastases are mostly likely to be from prostate cancer; whereas in women, most dural metastasis arises from a breast tumor. Dural metastases may present years after the primary tumor; however, most often they are seen in the context of known extracranial cancers. Dural and/or calvarial bone metastasis are often compartmentalized by the tough dural membrane and may present as a biconvex or lenticular “epidural” lesion or a concavoconvex “subdural” lesion or involve only the skull and scalp (Figs. 29-3 and 29-4).15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree