Part 1 Preprocedural Cases

Case 1

Clinical History

Shortness of breath ( Fig. 1‑1 ).

Key Finding

Preprocedure management with a low risk of perioperative bleeding.

Top 3 Issues of Management

Procedure types. The image-guided procedures categorized as “low risk of bleeding that is easily detectable and controllable” are generally venous cases, tube exchanges, and superficial percutaneous nonvascular interventions. Vascular cases include dialysis access interventions, venography, central line removal, inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement, and peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement. Nonvascular cases include drainage catheter exchanges (e.g., biliary, urinary, abscess drains), thoracentesis, paracentesis, superficial biopsies, and superficial drains.

Laboratory testing. No routine laboratory testing is necessary prior to these procedures, except in the setting of warfarin anticoagulation or suspected liver disease. In these situations, international normalized ratio (INR) should be checked. Review of any laboratory results previously accomplished for the patient is also recommended.

Management of medications and blood products. Treatment with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or vitamin K is recommended if INR is greater than 2. Platelet transfusion is recommended for counts less than 50,000/µL. There is no specific threshold recommendation for red blood cell transfusion in the setting of anemia (although beware of patients who are below your typical threshold for transfusions in severe anemia whether a procedure is needed or not). Regarding medicines affecting coagulation, most adhere to the following consensus recommendations from the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR):

Warfarin: Target INR less than or equal to 2.

Low-molecular-weight heparin: Hold one dose (12 hours) prior to the procedure.

Clopidogrel: Hold for 5 days.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): No need to hold.

Long-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (e.g., abciximab [ReoPro]): Hold for 12 to 24 hours (with a target activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) ≤ 50 seconds or activated clotting time (ACT) ≤ 150 seconds).

Short-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (e.g., tirofiban (Aggrastat) or eptifibatide [Integrilin]): Hold immediately before the procedure.

Direct thrombin inhibitors (bivalirudin [Angiomax], dabigatran [Pradaxa], or argatroban): No recommendation made by the SIR.

Diagnosis

Symptomatic pleural effusion with INR 1.77; proceed with thoracentesis.

Pearls

These guidelines represent a threshold 80% consensus from experienced proceduralists.

Management recommendations assume no other coagulation deficits are present.

Non-proceduralists will try to get you to perform procedures outside these parameters, assuming that image guidance will mitigate bleeding risk. Do not thoughtlessly fall for this line of thinking.

Suggested Readings

Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, et al; Standards of Practice Committee, with Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Endorsement. Consensus guidelines for periprocedural management of coagulation status and hemostasis risk in percutaneous image-guided interventions. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23(6):727–736 Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, et al; Standards of Practice Committee, with Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Endorsement. Standards of Practice Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Addendum of newer anticoagulants to the SIR consensus guideline. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24(5):641–645Case 2

Clinical History

Solitary 2.5 cm hepatocellular carcinoma, status postconventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) 1 month previous, for CT-guided focal tissue ablation. Normal complete blood count and coagulation panel (Fig. 2‑1).

Key Finding

Preprocedure management with a high risk of perioperative bleeding.

Top 3 Issues of Management

Procedure types. The list of image-guided procedures categorized as “procedures with significant bleeding risk that are difficult to control or detect” are generally cases with large-diameter needles or probes that create new pathways through solid, vascular organs. Vascular cases include transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) creation. Nonvascular cases include renal biopsy, new tract biliary interventions (e.g., percutaneous biliary drain), new transrenal urinary tubes (e.g., percutaneous nephrostomy tubes), and complex ablations (e.g., renal mass ablation).

Laboratory testing. Prior to these procedures, current laboratory testing should include INR, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (if the patient is on unfractionated heparin), hematocrit, and platelet count.

Management of medications and blood products. Treatment with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or vitamin K is recommended if INR greater than 1.5. Heparin cessation or reversal should occur if aPTT is greater than 1.5 times control. Platelet transfusion is recommended for counts less than 50,000/µL. There is no specific threshold recommendation for red blood cell transfusion in the setting of anemia (some use a hematocrit of 28). Regarding medicines affecting coagulation, the following guidelines should be considered:

Warfarin: Hold for 5 days before the procedure; goal INR less than or equal to 1.5.

Aspirin: Hold for 5 days.

Unfractionated heparin: Hold for 2 to 4 hours (goal aPTT ≤ 1.5 times control).

Low-molecular-weight heparin: Hold two doses or 24 hours before procedure.

Thienopyridine, clopidogrel (Plavix): Hold for 5 days (ticlopidine [Ticlid] hold for 7 days).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Short- acting (e.g., ibuprofen) 1 day; intermediate-acting (e.g., naproxen) 2 to 3 days; long-acting (e.g., meloxicam) 10 days.

Long-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: Hold for 24 hours (target aPTT ≤ 50 seconds; activated clotting time [ACT] ≤ 150 seconds).

Short-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: Hold for 4 hours.

Direct thrombin inhibitors: Hold off on procedure unless emergent.

Direct thrombin inhibitors (emergent case): Argatroban hold for 4 hours; bivalirudin (Angiomax) hold for 2 to 3 hours (3–5 hours if creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≤ 50 mL/min); dabigatran (Pradaxa) hold for 2 to 3 days (3–5 days if CrCl ≤ 50 mL/min).

Fondaparinux (Arixtra): Withhold 2 to 3 days (3–5 days if CrCl ≤ 50 mL/min).

Diagnosis

Solitary hepatocellular carcinoma for focal tissue ablation, which is a high risk of bleeding procedure. Screening parameters were normal, and the patient was not on any coagulation altering medications. Nonetheless, he still experienced a significant bleed. Fortunately, this was able to be managed without open surgery.

Pearls

A time lapse of 5 half-lives for a particular agent leaves about 3% residual drug activity and is frequently used as a means of normalizing a patient’s bleeding risk.

These are consensus guidelines. The risk of cardiovascular or thromboembolic events must weigh in on the complex decision to withhold certain pharmacologic agents versus the risk of bleeding and managing periprocedural bleeding.

Suggested Readings

Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, et al; Standards of Practice Committee, with Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Endorsement. Consensus guidelines for periprocedural management of coagulation status and hemostasis risk in percutaneous image-guided interventions. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23(6):727–736 Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, et al; Standards of Practice Committee, with Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Endorsement. Standards of Practice Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Addendum of newer anticoagulants to the SIR consensus guideline. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24(5):641–645Case 3

Clinical History

Patient with history of hepatitis C liver failure presents with new right mandibular pain and swelling. The patient’s inpatient care team is requesting gastrostomy tube placement (Fig. 3‑1).

Key Finding

Preprocedure management with a moderate risk of perioperative bleeding.

Top 3 Issues of Management

Procedure types. Vascular cases considered “moderate risk of bleeding” include arteriography with or without arterial intervention (up to 7-F devices), venous intervention, transjugular liver biopsy, and tunneled central venous catheter placement with or without a subcutaneous pocket. Nonvascular cases include deep abscess drainage or biopsy (e.g., lung or liver biopsy), percutaneous cholecystostomy, new gastrostomy, simple radiofrequency ablation (e.g., ablation of a superficial osteoid osteoma), and spine intervention (e.g., vertebroplasty, lumbar puncture, epidural injection).

Laboratory testing. Prior to these procedures, coagulation parameters should be checked. Review any other laboratory results already accessioned, but routine complete blood counts are not required.

Management of medications and blood products. Treatment with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or vitamin K is recommended if international normalized ratio (INR) is greater than 1.5. Heparin cessation or reversal should be considered if activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is greater than 1.5 times control. Platelet transfusion is recommended for counts less than 50,000/µL. There is no specific threshold recommendation for red blood cell transfusion in the setting of anemia. Regarding medicines affecting coagulation, the following guidelines should be considered:

Warfarin: Hold for 5 days; goal INR ≤ 1.5.

Aspirin: Do not withhold.

Unfractionated heparin: No consensus (trend toward goal aPTT ≤ 1.5 times control).

Low-molecular-weight heparin: Hold one dose or 12 hours before procedure.

Thienopyridine, clopidogrel (Plavix): Hold for 5 days (ticlopidine [Ticlid] hold for 7 days).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Do not withhold.

Long-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: Hold for 24 hours (target aPTT ≤ 50 seconds; activated clotting time [ACT] ≤ 150 seconds).

Short-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: Hold for 4 hours.

Direct thrombin inhibitors: Hold off on procedure unless emergent.

Direct thrombin inhibitors (emergent case): Argatroban hold for 4 hours; bivalirudin (Angiomax) hold for 2 to 3 hours (3–5 hours if creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≤ 50 mL/min); dabigatran (Pradaxa) hold for 2 to 3 days (3–5 days if CrCl ≤ 50 mL/min).

Fondaparinux (Arixtra): Withhold 2 to 3 days (3–5 days if CrCl ≤ 50 mL/min).

Diagnosis

Patient with indication for gastrostomy tube placement, but significant coagulopathy. Proceduralist should transfuse FFP, or administer vitamin K, with a target INR less than or equal to 1.5.

Pearls

If a procedure is not in the high- or low-risk category (shorter lists to understand and memorize), it is in the moderate list. However, lists are not absolute. Other patient factors may take a “moderate” case and alter it to a “high-risk” case (e.g., patient comorbidities, presence of multiple coagulation abnormalities, anatomy/adjacent vasculature).

Recommendations for warfarin, fondaparinux, thienopyridines, long-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and direct thrombin inhibitors are the same for “moderate-” and “high-risk” procedures.

Emergent cases may necessitate accomplishing the procedure prior to full work-up and management of bleeding risk, as delay could be more dangerous than proceeding in this manner. Judgment is necessary.

Suggested Readings

Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, et al; Standards of Practice Committee, with Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Endorsement. Consensus guidelines for periprocedural management of coagulation status and hemostasis risk in percutaneous image-guided interventions. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23(6):727–736 Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, et al; Standards of Practice Committee, with Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE) Endorsement. Standards of Practice Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Addendum of newer anticoagulants to the SIR consensus guideline. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24(5):641–645Case 4

Clinical History

A 75-year-old man with recently diagnosed pulmonary embolus, with new left flank pain and falling hematocrit while on anticoagulation (Fig. 4‑1).

Key Finding

Indications for IVC filter placement.

Top 3 Indications

Indications are per the evidence-based clinical practice guidelines provided by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP).

Acute proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT). When anticoagulant therapy is not possible due to the risk of bleeding (i.e., contraindicated or complications due to anticoagulation).

Acute pulmonary embolus (PE). When anticoagulant therapy is not possible due to the risk of bleeding (i.e., contraindicated or complications due to anticoagulation).

Chronic pulmonary emboli. Leading to pulmonary hypertension when undergoing pulmonary thromboendarterectomy.

Additional Considerations

Indications per the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR)

The SIR lists additional reasons to consider IVC filtration. For completeness sake, the following is their list of indications (nonevidence based):

PE/DVT with contraindications to anticoagulation.

PE/DVT with complications of anticoagulation.

PE/DVT with failure of anticoagulation (e.g., recurrent PE with adequate anticoagulation by laboratory values).

PE/DVT with inability to achieve adequate anticoagulation.

Propagation of DVT while on anticoagulation.

Massive PE with residual DVT in patient at further cardiopulmonary risk.

Free-floating iliocaval thrombus.

DVT/PE with severe cardiopulmonary disease (i.e., poor reserve).

Severe trauma without DVT/PE documented.

Closed head injury, spinal cord injury, multiple long bone fractures without DVT/PE documented.

Medical conditions at high risk of PE/DVT.

Diagnosis

Pulmonary embolus with complication due to anticoagulation; IVC filter indicated.

Pearls

Retrospective studies show that ACCP guidelines are followed for filter placement in only 43.5% of cases done by interventional radiologist (39.9% by vascular surgeons; 33.3% by cardiologists).

“If you place them (IVC filters), you must take them out!”

U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends that implanting physicians and clinicians responsible for the ongoing care of patients with retrievable IVC filters consider removing the filter as soon as protection from PE is no longer needed.

Suggested Readings

Baadh A, Zikria JF, Rivoli S, Graham RE, Javit D, Ansell JE. Indications for inferior vena cava filter placement: do physicians comply with guidelines? J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23(8):989–995 http://www.jvir.org/retrieve/pii/S1051044312003910. Accessed May 30, 2018 Caplin DM, Nikolic B, Kalva SP, Ganguli S, Saad WE, Zuckerman DA. Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for the performance of inferior vena cava filter placement for the prevention of pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22(11):1499–1506Case 5

Clinical History

Cirrhosis with recurrent symptomatic right pleural effusions ( Fig. 5‑1 ).

Key Finding

Indications for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement.

Top 3 Indications

Refractory variceal bleeding from gastroesophageal varices. This is a common indication for TIPS but should generally not be used as the primary treatment option. TIPS should be reserved for the treatment of bleeding varices refractory to medicinal and endoscopic management only.

Recurrent ascites. TIPS is effective in ascites management. Control of ascites by TIPS is achieved in just over half of patients at 1 year, versus 20% in those receiving medical management with large-volume paracentesis. However, rates of encephalopathy are higher post TIPS than in the medical management with large-volume paracentesis group (55 vs. 39%). One-year survival between the two groups is not statistically different.

Hepatic hydrothorax. Liver transplantation is the best solution for patients suffering from hepatic hydrothorax. These individuals tend to have advanced liver disease with significant complications related to portal hypertension. In those who are not transplant candidates, TIPS has a role in refractory disease (continued effusion accumulation despite sodium restriction, diuretics, and repeated thoracentesis). If unable to perform TIPS, patients are relegated to frequent, repeated thoracentesis or surgical attempts to close defects in the diaphragm.

Additional Considerations

Additional indications per the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR): The SIR lists the following clinical situations where TIPS can be beneficial:

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (or other “intestine-opathy”).

Budd–Chiari syndrome.

Diagnosis

Hepatic hydrothorax as an indication for TIPS.

Pearls

Although controversial, some physicians advocate for TIPS creation in the setting of hepatorenal or hepatopulmonary syndromes.

Some surgeons consider TIPS to decompress large abdominal portosystemic collaterals prior to abdominal surgery.

Suggested Readings

Deltenre P, Mathurin P, Dharancy S, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in refractory ascites: a meta-analysis. Liver Int 2005;25(2):349–356 Haskal ZJ, Martin L, Cardella JF, et al; Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003; 14(9 Pt 2):S265-S270 Krok KL, Cárdenas A. Hepatic hydrothorax. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2012;33(1):3–10Case 6

Clinical History

A 45-year-old woman with alcoholic liver failure presenting with refractory ascites. No history of encephalopathy. Consult placed for interventional radiology (IR) team to consider patient for creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) (Fig. 6‑1).

Key Finding

Contraindications to TIPS creation.

Top 3 Contraindications

Hepatic failure. Rapidly progressive or severe liver failure makes TIPS dangerous, as TIPS will likely lead to exacerbation of said fulminant liver failure. With a Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of greater than 15 to 18, or a total bilirubin (Tbili) of greater than 4 (both indicating high 30-day mortality in addition to the risk of the procedure), TIPS should only be performed in the absence of any other option. TIPS is dangerous when done for ascites in a Child–Pugh C alcoholic cirrhotic, with ongoing alcohol use, and should be discouraged.

Extrahepatic physiology. Nonhepatic factors that can prevent safe TIPS creation include significant heart failure or valvular insufficiency, elevated heart pressures (especially right heart pressures), severe or uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy, sepsis, and severe or uncontrolled coagulopathy.

Anatomical considerations. Generally, a suitable hepatic vein and portal vein are required to create a TIPS (intuitively, patent vessels would seem to increase technical success rates). Masses or cysts in the liver may complicate placement. Generally, there are ways to manage these anatomical issues. However, these factors make an already technically demanding procedure, more dangerous and complex.

Additional Consideration

American Association for the Study of Liver Disease

(AASLD) breaks down contraindications that are absolute versus relative: Absolute contraindications include primary prevention of variceal bleeding (should only be done after failure of medical and endoscopic management), congestive heart failure, multiple hepatic cysts, uncontrolled infection or sepsis, unrelieved biliary obstruction, and severe pulmonary hypertension. Relative contraindications include hepatoma (especially centrally located), complete obstruction of all hepatic veins, portal vein thrombosis, severe coagulopathy (international normalized ratio [INR] > 5), thrombocytopenia (platelets < 20,000/cm3), and moderate pulmonary hypertension.

Diagnosis

Hepatic failure as contraindication to TIPS (Tbili >4; alcoholic Child-Pugh C; MELD 21).

Pearls

In the setting of urgent TIPS creation, a patient not being able to consent for him or herself is a negative predictive factor for a successful outcome.

The decision to place a TIPS is complex, and should involve an experienced gastroenterologist or hepatologist, an interventional radiologist, and, where available, a transplant physician.

Prior to TIPS, bleeding risk factors should be checked, along with liver and renal function tests. It is prudent to perform cross-sectional imaging looking for vessel anatomy, vessel patency, liver masses, and biliary obstruction.

Suggested Readings

Boyer T, Haskal Z. AASLD Practice Guidelines: the role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (tips) in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology 2010;51(1):1–16 Haskal ZJ, Martin L, Cardella JF, et al; Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14(9 Pt 2):S265-S270Case 7

Clinical History

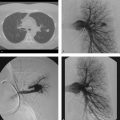

A 55-year-old man with acute shortness of breath and hypotension (Fig. 7‑1).

Key Finding

Relative contraindications to pulmonary angiography.

Top 3 Considerations

Severe pulmonary hypertension. Although somewhat controversial, many studies have pointed to pulmonary artery pressures and elevated right ventricular end-diastolic pressures, as risk factors for complications in pulmonary angiography. In studies where patients have elevated pressures, but do not suffer deleterious effects, the technique is changed to include reduction in flow rate and total volume of contrast, with selective angiograms of the left and right pulmonary arteries, instead of a main pulmonary artery injection. Despite alterations in technique, absolute safety is not guaranteed, as case reports exist of periprocedural mortality with even a 10-mL hand injection of contrast material. One study estimates a 2% procedural mortality in patients with right ventricular end-diastolic pressures of 20 mm Hg (normal, 0–8 mm Hg) and pulmonary artery systolic pressures of 70 mm Hg (normal, 15–25 mm Hg). Another study reports a mean pulmonary artery systolic pressure of greater than or equal to 58 mm Hg in those patients suffering major complications. The type of contrast used may also play a role in periprocedural complications, with the use of nonionic, iso-osmolar contrast preferred.

Left bundle branch block (LBBB). Presence of LBBB necessitates additional precautions during pulmonary angiography. Catheter passage through the right heart chambers can induce a right bundle branch block (RBBB). Therefore, preexisting LBBB, and induced RBBB, can lead to a complete heart block. Prophylactic temporary pacemaker insertion is recommended in this clinical scenario.

Amiodarone use. Although an effective antiarrhythmic drug, amiodarone has a few serious side effects. There are a series of case reports linking amiodarone use, and pulmonary angiography, to severe periprocedural respiratory distress that progresses to cardiopulmonary arrest and death, usually within 30 minutes. The mechanism of respiratory distress is unknown but suspected to be an acute exacerbation of amiodarone toxicity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree