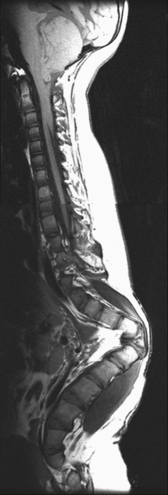

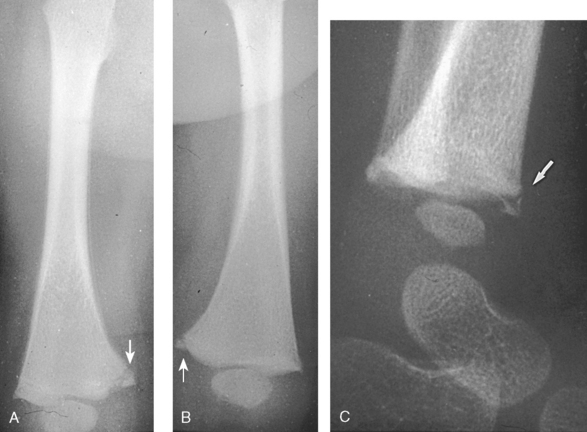

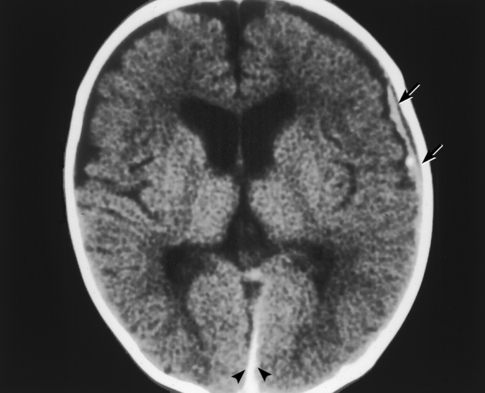

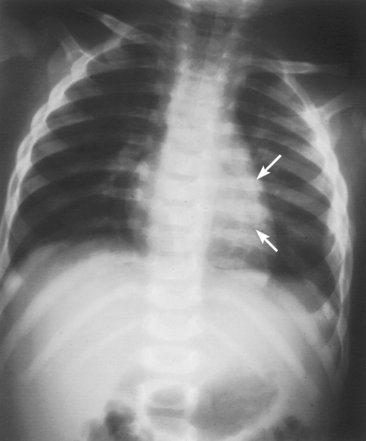

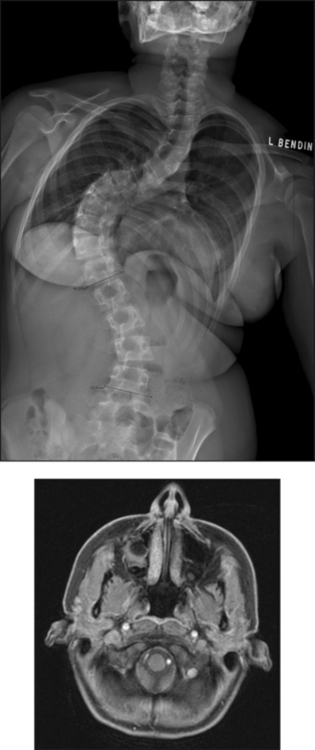

26 The environment in which patients are treated and recover plays a significant role in the recovery process. Research studies have compared the recovery course of patients whose hospital rooms looked out over parks with the recovery course of patients whose view was a brick wall. The patients who faced the park had a much shorter hospital stay than the other patients, and they required considerably less pain medication. With these differences in mind, the patient care center at SickKids (Toronto) was designed and built as an atrium (Fig. 26-1). Each patient room receives natural light, either by facing outside or overlooking the atrium, which receives natural light from the glass roof. Although it is easy to see how children can be amused by Miss Piggy and the barnyard animals that fly across the atrium, the environment does not have to be this elaborate to be appreciated by children. Small measures can be taken at relatively little cost to make a child’s hospital stay more comfortable. Gender-neutral toys or activities such as a small table and chairs with crayons and coloring pages are most appropriate. (Children should be supervised to prevent them from putting the crayons in their mouths.) Books or magazines for older children are also good investments. The child life department of the hospital can provide advice and the most appropriate recommendations (Fig. 26-2). • If the child is capable of understanding, direct the explanation to the child and use age-appropriate language (discussed later). The parents will listen and consequently understand what is expected. Communicating in this way puts the parents more at ease and increases their confidence in the radiographer’s skills. They appreciate the fact that their child has been made the focus of attention. • If the child is too young to comprehend, direct the explanation to the parent, explaining in simple sentences what is going to happen and what is expected of the parent. The importance and value of simple sentences cannot be overemphasized. People in stress-filled situations do not think as clearly as they normally do, and many parents in this setting are under stress. Successful communication involves the use of short sentences repeated once or twice in a soothing tone. When approaching an agitated parent, the radiographer should observe the following guidelines: • Remain calm and speak in an even tone, remembering that fear and frustration may be the cause of the agitation. • Use phrases such as “My name is …. I can identify with how you must be feeling and can appreciate your concern,” followed by “Let me explain to you what is happening.” • If possible, escort the parent to a nearby room to continue the explanation and listen to the parent’s concerns without interruption; this can avoid an unwanted scene in the waiting room. The degree of parent participation depends on the following factors: 1. The general philosophy of the department 2. The wishes of the parent and patient 3. The laws of the state or province regarding radiation protection 1. The parent can watch the child if the attention of the radiographer or radiologist is directed to the equipment or the fluoroscopic monitor. 2. The radiographer may need to leave the room. 3. The parent can assist with immobilization if needed (where permitted). 4. The parent who witnesses an entire procedure has little room for doubt about professional conduct. • Greet the patient and parent in the waiting area with a smile. • Bend down to talk to the child at the child’s eye level. • Take a moment to introduce yourself and ensure that you identify the correct patient; then state briefly what you are going to do. • Suggest, rather than ask, the child to come and help you with some pictures. This firm, yet gentle approach avoids creating the idea that the child has a choice. After all, the patient may be tempted to be emphatic and say “no.” • Use sincere praise. This is a powerful motivator, no matter what the age of the patient. Praise for young children (3 to 7 years old) should be immediate. Children have short attention spans and often expect to receive rewards immediately. The reward should be linked directly to the task that has been well done. Use phrases such as “You sat very still for me, thank you” or “You took a nice, big breath in for that picture, and I am going to ask you to do it again for the next one.” • When the outcome will be the same, give children an option: “Would you like Mom to help lift you up on the table, or may I help you?” or “We have two pictures to do. Which would you like first—the one with you sitting down or the one with you lying down?” • Employ distraction techniques. As radiographers develop confidence in basic radiography skills and adapting these skills for children, they find themselves able to engage in chatter and distraction techniques, making the experience as pleasant as possible for the child. Ask the child about brothers, sisters, pets, school, or friends—the topics are limitless. As homework, watch a few popular children’s cartoons. Communication is improved when the radiographer can build rapport with a child, and learning a few more distraction techniques is helpful. • Answer all questions truthfully— regardless of their nature. Maintaining honesty is crucial in all communications with children. Confidence and credibility built by the previous strategies can be lost if the truth is withheld. The secret is to not volunteer information too early or dwell on unpleasantness. • Give explanations at the child’s eye level by bending down or by sitting the child on the radiographic or scanner table. • Use the camera analogy to describe the x-ray tube, taking care to explain that the tube may move sideways but will never come down and touch the child. • Avoid any unnecessary equipment manipulation. • Encourage the child gently as the child attempts to cooperate—then praise the cooperation. A 5-year-old child has typically reached a time that is rich in new experiences. Reactions can differ widely, depending on how at ease the child feels with a given environment. Children in this age group generally want to perform tasks correctly, and they enjoy mimicking adults. When a 5-year-old feels confident, that child will act like a 6-, 7-, or 8-year-old; however, when afraid or worried, that same child may cling to parents and become reticent and uncooperative. Constant reassurance and simple explanations help in such moments. Take a moment to show the child how the collimator light works and let the child turn it on—for a child, this is as much fun as pressing the buttons in an elevator (Fig. 26-3). For a radiographer who is not accustomed to working with children, the perfect group to start with is 6- to 8-year-olds. These children are generally accommodating and eager to please. They are modest and embarrass easily, so their privacy should be protected. These children are the easiest age group with which to communicate; they appreciate being talked through the procedure, which gives them less time to worry about their surroundings or the procedure itself. Anatomic landmarks are easy to locate for positioning, and body habitus evens out nicely—the “big belly” of the toddler disappears. From an imaging standpoint, the bones are maturing, with the increased calcium content enhancing subject contrast (Fig. 26-4). Image is important to preteens and adolescents. Although they are better able to understand the need for hospitalization, they are upset by interference in their social and school activities. They are particularly concerned that as a result of the injury they may not be able to return to their preinjury state. These patients require, and often demand, clear explanations. Health care workers should not be surprised by the frankness of their questions and should be prepared for some discussion.1 Adolescents want to be treated as adults, and the radiographer must exercise judgment in assessing the patient’s degree of maturity. The radiographer should become familiar with the local statutes regarding consent to understand when children are deemed to be responsible for themselves.2 • Preface the questioning by stating that information of a sensitive nature needs to be obtained for radiation safety. • Ask a 10-, 11-, 12-, or 13-year-old girl if she has started menstruating. If the response is affirmative, continue by saying that a slightly more sensitive question needs to be asked. Then ask if there is any possibility of pregnancy. • Simply but tactfully ask girls 14 years and older if there is any chance of pregnancy. Judging from the patient’s expression and response, decide how to continue. • Differing levels of maturity call for different explanations. If necessary, apologize for the need to ask sensitive questions and assure the patient that the same questions are asked of all girls of this age. • Follow the questioning with an explanation that it is unsafe for unborn babies to receive radiation. Children with physical and mental disabilities • Direct communication toward the child first. All children appreciate being given the opportunity to listen and respond. Similar to all patients, these children also want to be talked to rather than talked about. • If this approach proves ineffective, turn to the parents. Generally, the parents of these patients are present and can be very helpful. In strange environments, younger children may trust only one person—the parent. In that case, the medical team can gain cooperation from the child by communicating through the parent. Parents often know the best way to lift and transfer the child from the wheelchair or stretcher to the table. Children with physical disabilities often have a fear of falling and may want only a parent’s assistance. • After introducing yourself, briefly explain the procedure to the child. • Place the wheelchair or stretcher parallel to the imaging table, taking care to explain that you have locked the wheelchair or stretcher and will be getting help for the transfer. These children often know the way they should be lifted—ask them. They can tell you which areas to support and which actions they prefer to do themselves. • Greet the patient and parents, and then describe the procedure using short, simple, and often-repeated sentences. • When patients and parents speak with a tone of urgency and frustration, this usually stems from fear; maintain a calm perspective in these situations to ensure a smooth examination. • Increase the level of confidence the parents and child have in your abilities with frequent reassurance presented in a calming tone. (The reassurance referred to here is reassurance that the radiographer knows how to approach the situation, not reassurance that all will be well with respect to the injury.) • In emergency examinations, as with any other examination, ensure that only one caregiver is giving the child instructions and explanations. (Caregivers include parents, nurses, physicians, and radiographers, all of whom may be present.) Much greater success is achieved when only one person speaks to the child. • After completing the procedure, ensure that you have the parents’ attention. Speaking slowly, give clear instructions about where to wait and what to expect. Depending on the level of care being provided, children may arrive in the imaging department with chest tubes, intravenous (IV) infusions (including central venous lines), colostomies, ileostomies, or urine collection systems. Usually these children are inpatients, but in many instances outpatients (particularly in interventional cases) arrive in the department with various tubes in situ (e.g., gastrostomy or gastrojejunostomy tube placements). The radiographer must be aware of the purpose and significance of these medical adjuncts and know the ways to care for a patient with them (see Figs. 26-46 and 26-47). A competent and caring radiographer takes note of the following: 1. What are the specific instructions regarding the care and management of the child during the child’s stay in the department? 2. Will a nurse or another health care professional accompany the child? 3. Will physical limitations influence the way the examination is performed? Hospital policy and the availability of nursing staff within the imaging department determine the amount of involvement the radiographer has with the management of IV lines. The radiographer must be able to assess the integrity of the line and must know the measures to take in the event of problems.1 The radiographer should follow all precautions outlined by the physician and nursing unit responsible for the child. Respiratory, enteric, or wound precautions for handling a patient are usually instituted to protect staff members and other patients. Isolation procedures are instituted to protect a patient from infection. Protective isolation is used with burn victims and patients with immunologic disorders. The protective clothing worn by staff members may be the same in either situation, but the method of discarding the clothing would be different.1 To avoid hypothermia, premature infants should be examined within the infant warmer or isolette whenever possible. General radiography must be performed with a portable or mobile unit. (See Chapter 28 for a discussion of mobile radiography.) The radiographer should take great care to prevent the infant’s skin from coming in contact with IRs. Covering the IR with one or two layers of a cloth diaper (or equivalent) works well; however, the material should be free of creases because these produce significant artifacts on neonatal radiographs. • Elevate the temperature in the room 20 to 30 minutes before the arrival of the infant. The ambient temperature of the imaging room is usually cool compared with the temperature of the neonatal nursery. • When increasing the temperature is impossible, prepare the infant for the procedure while the infant is still in the isolette and remove the infant for as brief a period as possible. • Use heating pads and radiant heaters to help maintain the infant’s body temperature; however, these adjuncts are often of limited usefulness because of necessary obstructions such as the image intensifier. If heaters are used, position them at least 3 ft (1 m) from the infant. • Place large bags of IV solutions, prewarmed by soaking in a sink of warm water, beside the infant to serve as small hot water bottles. • Monitor the infant’s temperature throughout the procedure, and keep the isolette plugged in to maintain the appropriate temperature. Patients with myelomeningoceles are cared for in the prone position. Whenever possible, radiographic examinations of these patients should be performed using the prone position until the defect has been surgically repaired and the wound healed. The primary imaging modalities used in the investigation and follow-up care of myelomeningoceles include ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 26-5). • Insist that the patient be accompanied by and transported into the radiographic room with the responsible physician. The patient must be supported in the upright position with an emergency physician monitoring the airway at all times. • Do not proceed with the necessary lateral radiograph of the nasopharynx or soft tissues of the neck without the presence of the physician. • Perform the single upright lateral image without moving the patient’s head or neck (Fig. 26-6). • Take extreme care to ensure the child does not panic, cry, or become agitated. Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a disease characterized by brittle bones. The approach and management need to be altered significantly in the imaging department to accommodate patients with OI. Children with OI are prone to spontaneous fractures or fractures that occur with minimal trauma. Although OI can vary in severity, patients with this disease need to be handled with extreme care by an experienced radiographer (Fig. 26-7). • Constantly reassure the parent and patient that every part of the procedure will be explained before it is attempted. • For the best results, explain the desired position to the parent in simple terms—for example, “the knee needs to point to the side” for a lateral image. Allow the parent to do the positioning. • Ask an older child for advice on the way the child should be moved or lifted. • If possible, take the radiographs with the child in the bed or on the stretcher. This is often possible, given the patient’s small physical stature. Although no universal agreement exists on the definition of child abuse, the radiographer should have an appreciation of the all-encompassing nature of this problem. Child abuse has been described as “the involvement of physical injury, sexual abuse or deprivation of nutrition, care or affection in circumstances, which indicate that injury or deprivation may not be accidental or may have occurred through neglect.”1 Although diagnostic imaging staff members are usually involved only in cases in which physical abuse is a possibility, they should realize that sexual abuse and nutritional neglect are also prevalent. It is mandatory in all states and provinces in North America for health care professionals to report suspected cases of abuse or neglect. The radiographer, while preparing or positioning the patient, may be the first person to suspect abuse or neglect (Fig. 26-8). The first course of action for the radiographer should be to consult a radiologist (when available) or the attending physician. After this consultation, the radiographer may no longer have cause for suspicion because some naturally occurring skin markings mimic bruising. If the radiographer’s doubts persist, the suspicions must be reported to the proper authority, regardless of the physician’s opinion. Recognizing the complexity of child abuse issues, many health care facilities have developed a multidisciplinary team of health care workers to respond to these issues. Radiographers working in hospitals have access to this team of physicians, social workers, and psychologists for the purposes of reporting their concerns; others are advised to work through their local Children’s Aid Society or appropriate organization. Plain image radiography, often the initial imaging tool, can reveal characteristic radiologic patterns of skeletal injury. Clear evidence of posterior rib fractures, corner fractures, and bucket-handle fractures of limbs are considered classic indicators of physical abuse (Fig. 26-9). All imaging modalities play a role in the investigation of suspected child abuse. After plain radiography, nuclear medicine is often the next investigative tool of choice (Fig. 26-10). CT with three-dimensional reconstruction has contributed to differentiating cases of actual abuse from accidental trauma (Fig. 26-11). The presence of numerous fracture sites at varied or multiple stages of healing can also indicate long-term or ongoing abuse. These cases are often viewed by nonradiologic staff members (e.g., lawyers) and imaging professionals. Evidence of injury must be readily apparent, especially because pediatric fractures at an early age can remodel totally over time, providing no clear evidence of earlier fractures. The radiographer’s role is to provide physicians with diagnostic radiographs that show bone and soft tissue equally well. Referring physicians depend on the expertise of the diagnostic imaging service for the detection of physical abuse, and radiologists are able to estimate the date of the injury based on the degree of callus formation or the amount of healing. The radiographer observes the following guidelines when dealing with a case of possible child abuse: • Give careful attention to exposure factors and the recorded detail shown for limb radiography. Imaging systems yielding high detail are recommended for cases of suspected child abuse because the associated skeletal injuries are often very subtle (Fig. 26-12).

PEDIATRIC IMAGING

Atmosphere

WAITING ROOM

Approach

Dealing with an agitated parent

Parent participation

APPROACHING THE CHILD

Children 2 to 4 years old

Children 5 years old

School-age children 6 to 8 years old

Adolescents

APPROACHING PATIENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Patient Care: Psychological Considerations

EMERGENCY PATIENT

Patient Care: Physical Considerations

ISOLATION PROTOCOLS AND STANDARD BLOOD AND BODY FLUID PRECAUTIONS

Patient Care: Special Concerns

PREMATURE INFANT

MYELOMENINGOCELE

EPIGLOTTITIS

OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA

SUSPECTED CHILD ABUSE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

PEDIATRIC IMAGING