13 Pediatric IR Generally speaking, treatment used in adult IR can be applied to most pathology seen in the pediatric population. There are some differences, however, in the more extensive involvement of the anesthesia team, the increased attention to minimizing radiation exposure, and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to treating pediatric patients. Procedures that would generally require minimal sedation or local anesthesia for adults often require deep sedation or general anesthesia for pediatric patients. Neonates and infants can often have minor procedures such as lumbar puncture or peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion with the use of oral sucrose for mild analgesia. Distraction techniques (toys, music, etc.) can be provided by child life experts during the procedure. Older children, on the other hand, may require sedation or general anesthesia even for minor procedures. The developmental stage of the child also should be considered in planning the procedure. As such, anesthesiologists are far more involved in pediatric IR than in adult IR. There are two types of vascular anomalies: vascular tumors and vascular malformations (▸Table 13.1). The most common type of vascular tumor in the pediatric world is the benign infantile hemangioma. Infantile hemangiomas show up in the first year of life, commonly on the skin, in the liver, or within the GI tract. Most infantile hemangiomas proliferate in the initial few months of life then regress. Infantile hemangiomas generally do not cause issues, and are managed medically with β-blockers. IR rarely plays a role in the management of vascular tumors, and is usually only involved when the hemangioma results in a large vascular shunt. If large enough (typically a liver hemangioma), shunting can potentially lead to high-output cardiac failure. Another indication for intervention is if the hemangioma is in a sensitive location, near the airway, eye, etc. In contrast, vascular malformations are a relatively much more common source of referrals for pediatric IR. Vascular malformations are due to errors in vascular morphogenesis rather than proliferation of the endothelial cells. Vascular malformations are classified as either low-flow or high-flow lesions, referring to the movement of blood through the malformation. From an IR standpoint, it’s helpful to maintain this organization in your head since it reflects the significant difference in how these types of malformations are treated. Table 13.1 Vascular anomalies seen in children

13.1 Vascular Anomalies

Vascular tumors | Vascular malformations |

Infantile hemangiomas | High-flow malformations: |

Capillary hemangiomas | Low-flow malformations: |

Low-Flow Vascular Malformations

Low-flow malformations include capillary, venous, and lymphatic malformations. While capillary malformations are generally treated by dermatologists and plastic surgeons, venous and lymphatic malformations are seen by pediatric IR.

Venous malformations (VMs) are the most common vascular malformation. They can occur anywhere in the body, but most commonly in the head/neck or extremities. VMs arise due to a deficiency of smooth muscle cells lining the vessel wall, which consequently causes the vein to dilate and form vascular lakes. The malformations are present at birth, but are typically not detected until they grow (often during puberty).

A VM can present in a number of different ways. Once big enough, the patient or a parent might see the lesion underneath the skin. Superficial VMs look like soft blueish masses, and can sometimes bleed. They tend not to be as well-circumscribed as vascular tumors. Deeper VMs within intramuscular, intraosseous, or even intracranial compartments may not be directly visible. As these deeper malformations grow, they can lead to pain and swelling. There is also a predisposition for thrombus formation since blood can be stagnant within VMs.

Lymphatic malformations (LMs), in contrast, are usually detected at birth as soft, compressible masses in the head/neck area or sometimes in the limbs. The most common type of LM is a cystic collection of lymph that is caused by obstruction of the lymphatic channels. The natural course of lymphatic malformations is one of expansion and contraction. Expansion is often the result of a certain stimuli (bleeding or infection of the lesion), while contraction can occur spontaneously as lymph drains out of the lesion.

Diagnosis of the low-flow malformations is predominantly clinical. Physical exam of a patient presenting with the symptoms described above is often enough to make the diagnosis in the hands of an experienced clinician. Key exam findings can differentiate a VM from an LM. When VMs are compressed and released, they refill with blood quickly. They also tend to get bigger if the involved body part is placed in a dependent position. Differentiating between them is not always clear-cut, as certain malformations have components of both.

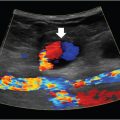

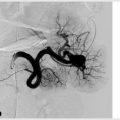

Imaging is performed when the diagnosis needs confirmation or for treatment planning. Imaging characteristics can sometimes help differentiate between VMs and LMs. The tendency for thrombus formation with VMs sometimes leads to formation of intralesional phleboliths, which may be a clue on plain films or cross-sectional studies. Ultrasound of a venous malformation most commonly shows a heterogeneous, but mostly hypoechoic compressible mass, with little or no Doppler flow. Lymphatic malformations are similar, but can be unilocular and may have internal septations. MRI is required to fully delineate the extent of tissue involvement for both VMs and LMs, and is done after an initial ultrasound (▸Fig. 13.1). A venous malformation will appear on MRI as cyst-like vascular channels that are hyperintense on T2-weighted images. LMs that have had prior hemorrhage may show a fluid–fluid level. MRA or conventional angiography of low-flow malformations in most cases will look relatively normal, so these are not very useful for diagnosis. Direct puncture and contrast administration will define the lesion during IR treatment.

Both lymphatic and venous malformations may become problematic due to their location. They can be cosmetically displeasing if superficial, or compress nearby vital structures. Each also has its own unique complications. Lymphatic malformations carry a risk of infection, while venous malformations are prone to thrombose and become painful. Any of these issues are considered indication for treatment.

Since vascular malformations are relatively rare, most cases will be sent to a regional referral center and approached by a multidisciplinary team to determine a treatment plan. This often includes pediatrics, plastic surgery, orthopedics, and IR. Referrals for vascular malformation treatment not uncommonly are sent to us with an incorrect diagnosis, so the first step is reviewing the outside studies to confirm the identity of the lesion and determine if there is an indication for treatment. Conservative measures and reassurance are reasonable for many of these patients.

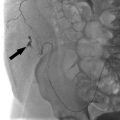

Low-flow malformations that require intervention can be treated with surgery, IR sclerotherapy, or a combination of both. The basic concept behind sclerotherapy for low-flow malformations is to inject an irritant substance into the malformation (▸Fig. 13.2). This causes injury to the endothelial cells, inducing fibrosis and involution. The procedure is ultrasound-guided, fluoroscopy-guided, or occasionally CT-guided. For VMs, the sclerosing agent used is either ethanol or sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS). Ethanol is the more effective of the two, but is associated with worse side effects and is rather painful for conscious sedation patients. The same can be used for LMs, as well as a doxycycline-based sclerosant. Usually patients are brought back for multiple sclerotherapy sessions to achieve symptomatic relief.