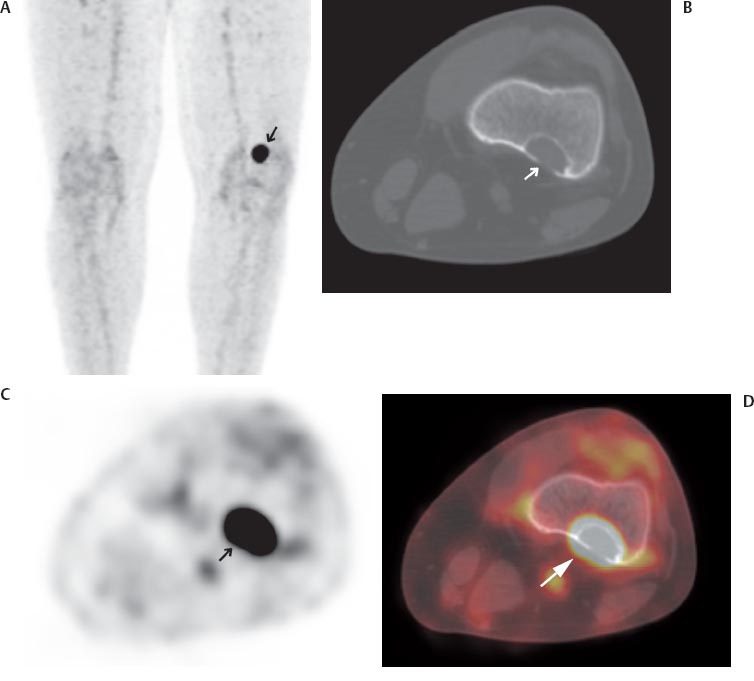

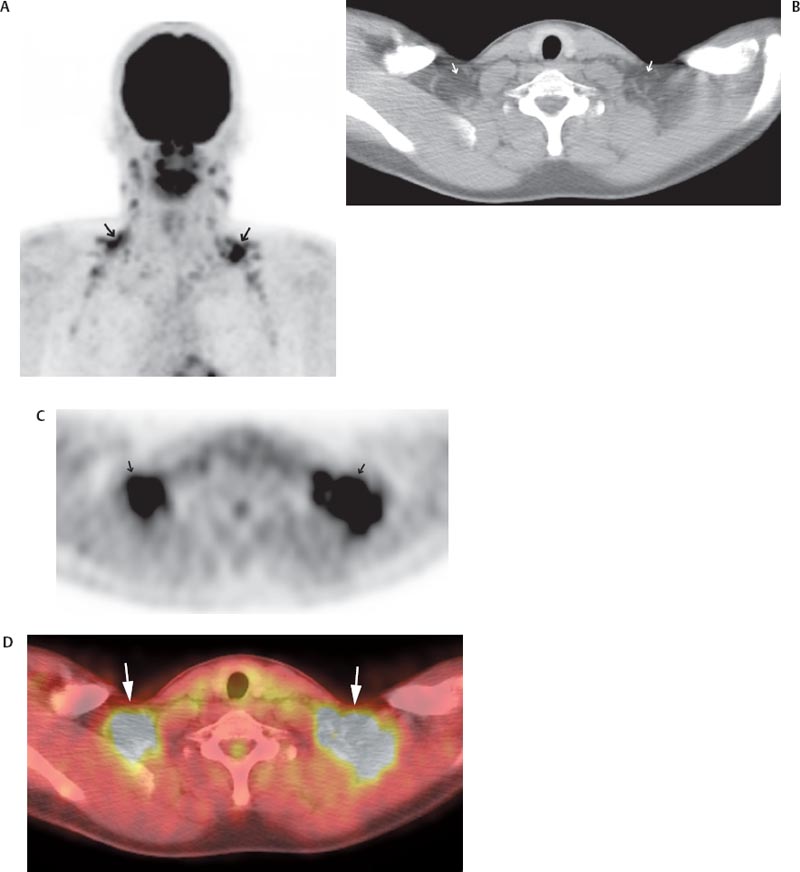

IV The use of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in children requires consideration of several unique technical and logistic issues. Young children often require sedation for PET/CT, and personnel trained in the management of children are vital to patient safety. Pregnant guardians of young patients should not be allowed in the fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake room, and arrangements must be made for the supervision of such patients. Before administration of the radioisotope, young female patients themselves must be questioned regarding their childbearing potential. This delicate subject is best handled by a technologist with experience working with young girls. Additionally, interpretation of pediatric PET/CT imaging requires familiarity with pediatric anatomy and physiology because, compared with adults, children have more metabolically active brown fat and less retroperitoneal fat (Fig. 26.1).1 PET/CT is becoming an increasingly important adjunct to the care of the pediatric oncology patient. Several indications for its use in children are discussed herein. Fig. 26.1 A 16-year-old boy previously treated for Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) Maximum intensity projection positron emission tomography (MIP PET) image showing intense fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity in the supraclavicular areas (arrows) that is difficult to accurately localize by positron emission tomography (PET) alone. (B) This is coregistered axial computed tomography (CT). Coregistered axial (B) computed tomography (CT), (C) PET, and (D) fused PET/CT images allow confident localization of FDG activity to brown fat (arrows). Children often have abundant metabolically active brown fat, such as shown here. PET/CT has shown value in detecting bone metastases from primary Ewing sarcoma of bone and in the response evaluation of primary Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma. In children with soft tissue malignancies, PET/CT has shown value in identifying the site of an unknown primary tumor, staging, monitoring response to therapy, and detecting recurrence.

Nononcologic Applications

26

Pediatric PET/CT

M. Beth McCarville

Bone Tumors

Bone Tumors

Clinical Indication

Accuracy

Pearls

Pitfalls

Soft Tissue Tumors

Soft Tissue Tumors

Clinical Indication

Accuracy

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine