and Siddharth P. Jadhav2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch Pediatric Radiology, Galveston, TX, USA

(2)

The Edward B. Singleton Department of Pediatric Radiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract

This chapter deals with injuries of the pelvis and sacrum. Various types of fractures and other injuries are presented. MR is discussed where it significantly adds to evaluation of these injuries.

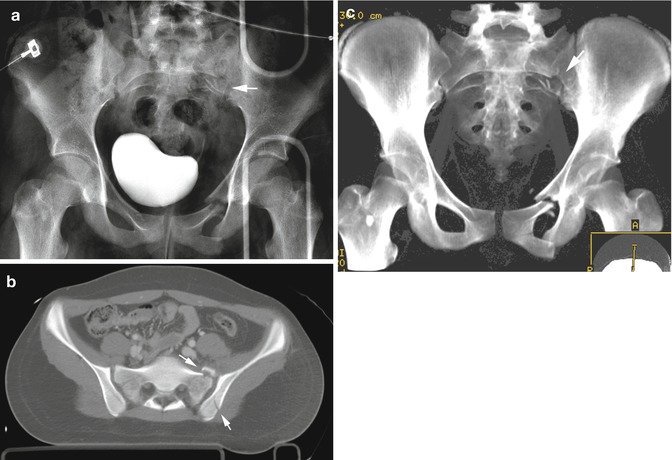

Fractures of the Sacrum

Sacral fractures usually are associated with pelvic injuries and overall may be difficult to detect. However, if one systematically compares the cortical margins of the sacral ala on one side to those on the other, disruption of their margins/accurate lines [1] provides a clue to the presence of a fracture (Fig. 8.1a). In addition to sacral fractures, many of these patients demonstrate associated sacroiliac joint separation and pelvic fractures. In this regard, CT scanning is more specific in confirming or initially detecting these injuries (Fig. 8.1b, c).

Fig. 8.1

Sacral fracture. (a) Note the distorted sacral ala on the left (arrow). Also note fractures through the pelvis on the same side. A minimal buckle fracture through the pubic bone is present on the right. (b) CT study demonstrates the sacral fracture (upper arrow) but also demonstrates an iliac wing fracture (lower arrow). In addition the sacroiliac joint on the left also is a little widened suggesting separation. (c) Reconstructed CT study more clearly demonstrates the sacral fractures (arrow)

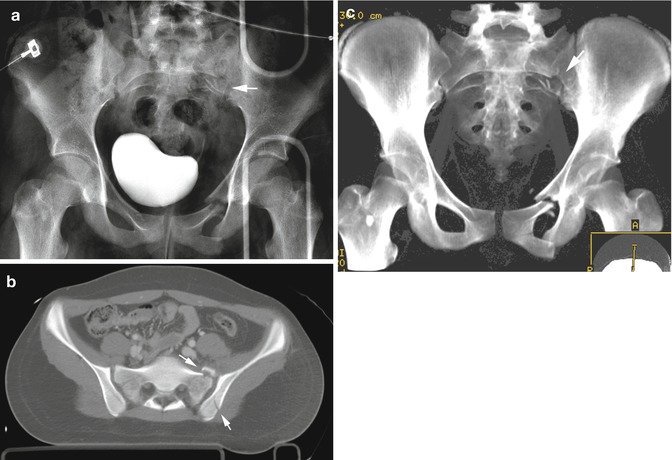

Fractures of the Pelvis

Pelvic fractures frequently are multiple and can range from simple buckle fractures to extensive fracture dislocations associated with internal organ or vascular injury. Most often these latter fractures are sustained in automobile accidents and of these fractures, fractures resulting in separation of the symphysis pubis, fractures through the acetabulum, and the so-called diametric (ring) fractures of the pelvis are considered unstable. These usually are finally imaged with CT and more often are seen in older children and adolescents.

Isolated pelvic fracture most commonly occur through the pubic bone or iliac wing. These can be overt or subtle and in infants and young children may manifest as simple buckle fractures (Fig. 8.2a). Multiple fractures are more common in older children (Fig. 8.2b–d). Acetabular [2] and acetabular rim fractures are not particularly common in childhood but can be seen in older children in association with posterior hip dislocations. They may be difficult to detect on plain films and in infants and young children, these fractures tend to occur through the triradiate cartilage.

Fig. 8.2

Pelvic fractures. (a) In this young child a buckle fracture through the pubic bone (arrow) is seen. (b) In this adolescent bilateral pelvic fractures are obvious (arrows). (c) CT study demonstrates the same comminuted fractures (arrows). (d) CT study through the upper pelvis demonstrates fractures through the iliac bones and sacrum. In addition there is widening of the sacral iliac joint (arrow)

Avulsion fractures of the pelvic bones commonly occur in children and the sites are shown in Fig. 8.3. In a study of 203 avulsion injuries in young athletes, the most common avulsion injury of the pelvic girdle involved the ischial tuberosity [3]. However, in our practice we have found that most often they are seen along the outer aspect of the iliac wing as anterior inferior or superior iliac spine fractures [4]. Thereafter, the next most common place is over the inferior aspect of the ischium. Less commonly they occur over the iliac crest and then off of the greater and lesser trochanters.

Fig. 8.3

Pelvis and upper femoral avulsion fracture sites. (1) Iliac crest, (2) anterior superior iliac spine, (3) anterior inferior iliac spine, (4) greater trochanter, (5) lesser trochanter, and (6) ischium. Most commonly these fractures occur at sites 2, 3, and 6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree