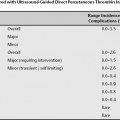

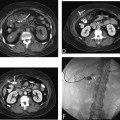

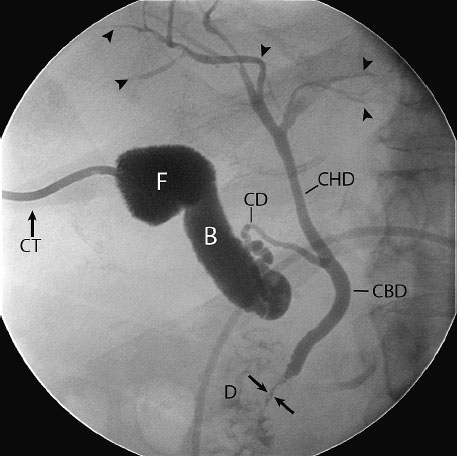

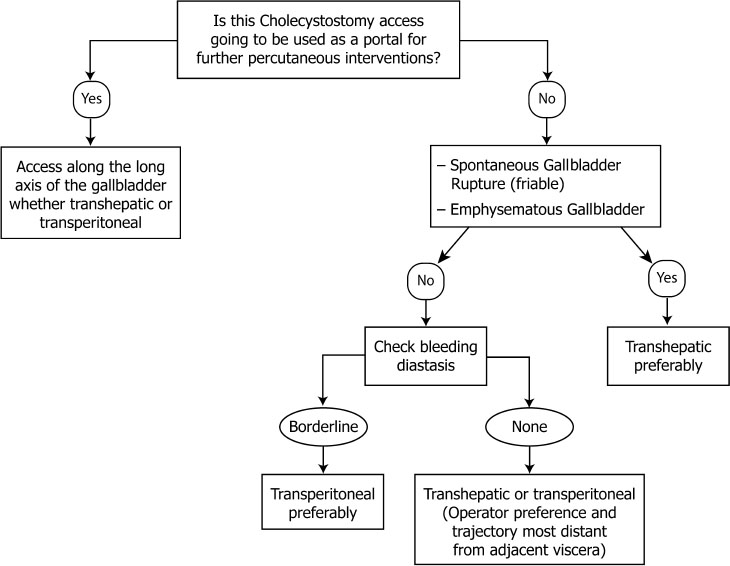

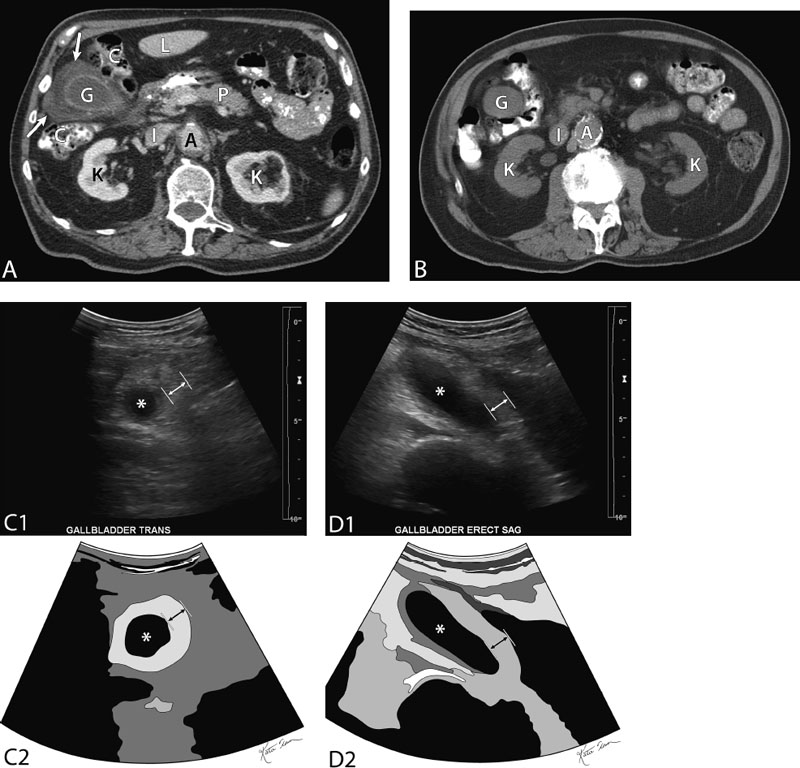

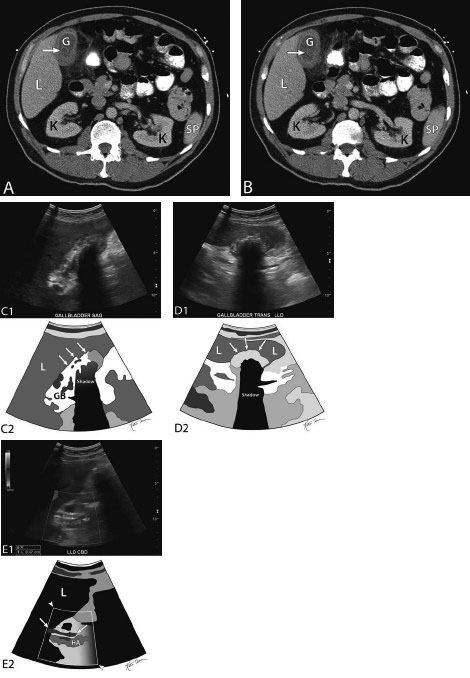

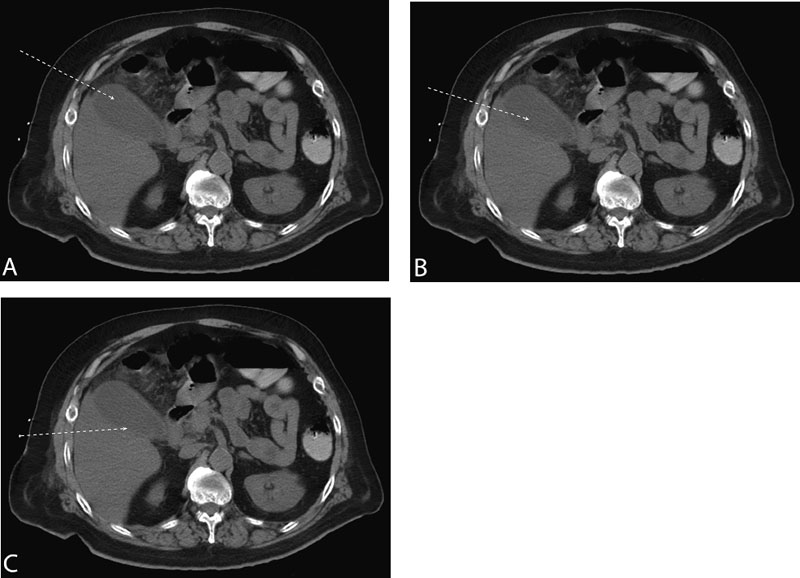

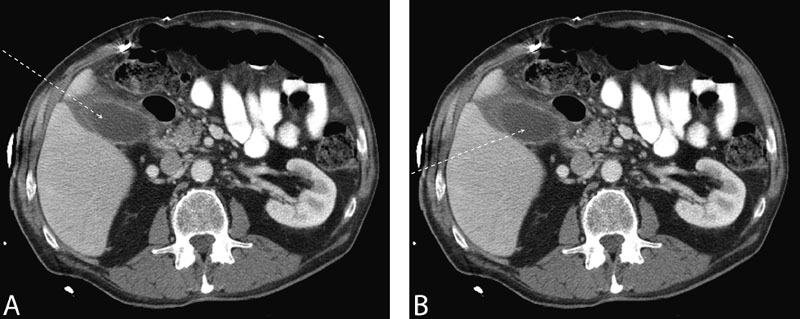

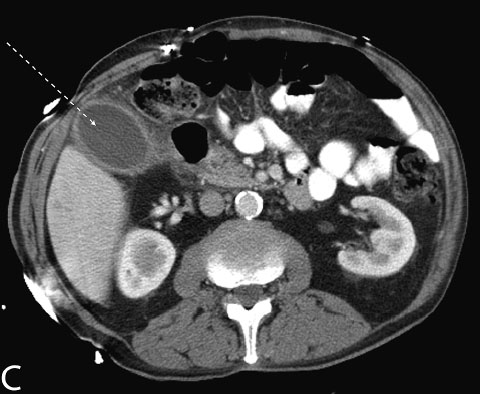

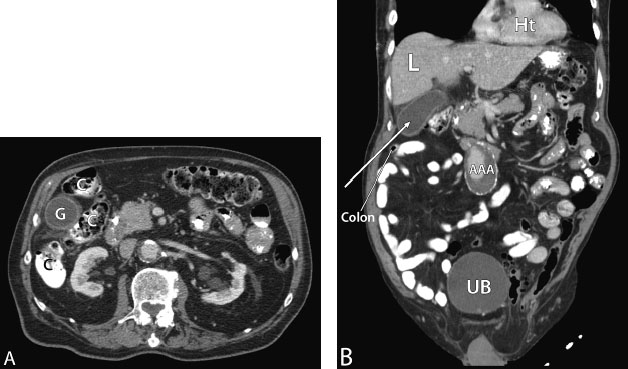

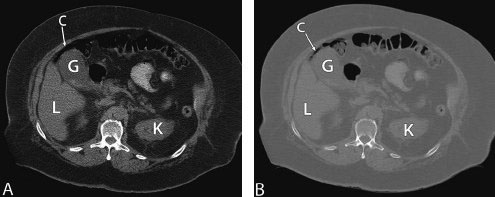

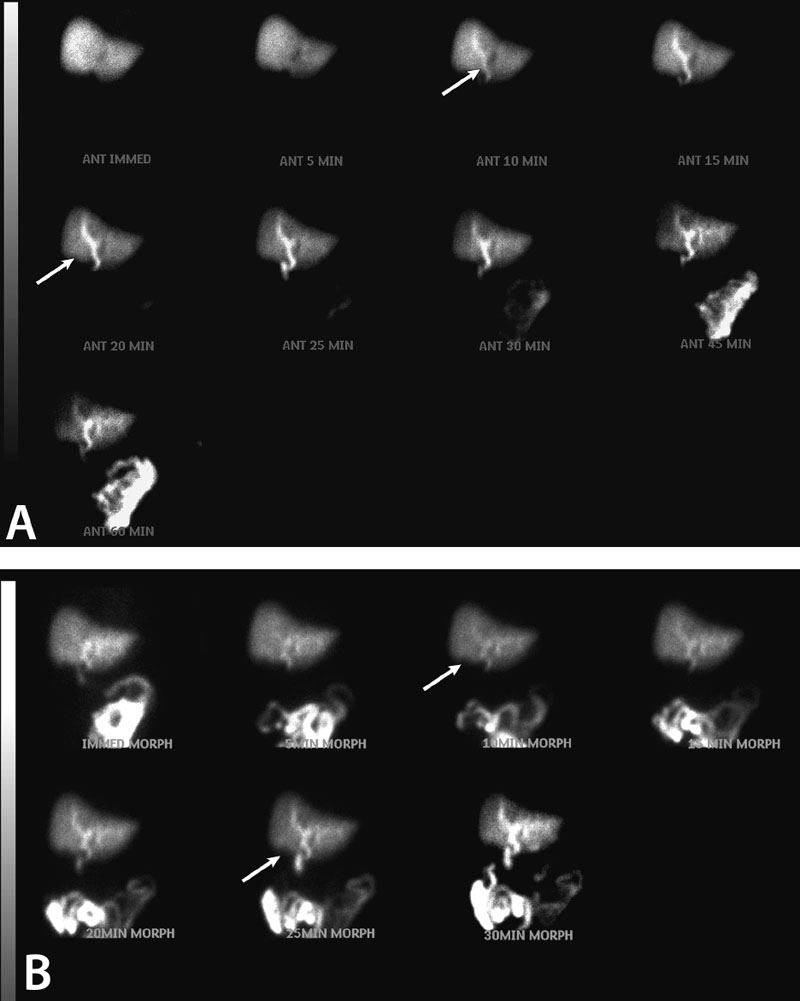

13 Percutaneous Cholecystostomy Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cholecystostomy was described first in 1979. It is a management alternative to cholecystectomy, mostly for nonsurgical candidates. Overall, cholecystectomy is the first-line treatment and percutaneous cholecystostomy is the second-line treatment. As a result, a contraindication to cholecystectomy (poor surgical candidate) should accompany the indications listed below for percutaneous cholecystectomy to be indicated fully. A soft indication is a patient who is a borderline nonsurgical candidate, who in the acute setting has high surgical morbidity. In this setting, cholecystostomy may be contemplated to resolve the acute situation (cholecystitis among other possible acute medical conditions) and plan for a subsequent elective procedure (cholecystectomy) under stable conditions. The following are indications of percutaneous cholecystostomy. Fig. 13.1 Transcholecystic cholangiogram. Fluoroscopic image demonstrating a cholangiogram through a cholecystostomy tube and a patent cystic duct. Details of the biliary tract including peripheral/intrahepatic bile ducts are seen (arrowheads). Notice the mamillated appearance of the fundus of the gallbladder (F, fundus of gallbladder; B, body of gallbladder; CD, cystic duct; CT, cholecystostomy tube; CHD, common hepatic duct; CBD, common bile duct; D, duodenum). (Arrows, level of sphincter of Oddi). The gallbladder can be accessed percutaneously from a strict transperitoneal approach or from a transhepatic approach (crossing a segment of liver to the gallbladder). The details of which and when an approach is better will be discussed in detail in the Technique section below ( Fig. 13.2 ). Fig. 13.2 Flowchart illustrating thought process of choosing transhepatic versus transperitoneal access to the gallbladder. Further transcholecystic percutaneous interventions include gallbladder stone extraction (transhepatic choledoscopy, or fluoroscopy), choledocholithiasis stone extraction (transhepatic choledoscopy, or fluoroscopy), and transcholecystic biliary drainage. Look for collaborative evidence of cholecystitis such as a thick gallbladder wall (>3 mm) or gallbladder stones (cholelithiasis) (Figs. 13.3 and 13.4). Fig. 13.3 Collaborative evidence of cholecystitis. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen just below the liver demonstrating a very thick gallbladder wall (arrows). Compare with the unenhanced CT of the same patient 3 months earlier in Fig. 13.3B (K, kidneys; L, liver; C, colon; P, pancreas; A, aorta; I, inferior vena cava [IVC]; G, gallbladder). (B) Nonenhanced axial CT image of the abdomen just below the liver of the same patient as Fig. 13.3A, however, 3 months earlier demonstrating a gallbladder with imperceptible walls (G). Compare with the contrast-enhanced CT of the same patient 3 months later (K, kidneys; A, aorta; I, IVC; G, gallbladder). (C) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the gallbladder (transverse on gallbladder) of the patient with the thick gallbladder wall in Figs. 13.3A and 13.3B (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). Again, noted is the thick gallbladder wall (two-way arrow) surrounding the gallbladder lumen (*). (D) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the gallbladder (long on gallbladder) of the patient with the thick gallbladder wall in Figs. 13.3A, 13.3B, and 13.3C (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). Again, noted is the thick gallbladder wall (two-way arrow) surrounding the gallbladder lumen (*). Fig. 13.4 Collaborative evidence of cholecystitis: cholelithiasis. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver demonstrating a thick gallbladder wall and what appears to be one or two stones (arrow) within the gallbladder (K, kidneys; L, kiver; G, gallbladder; Sp, spleen). (B) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image (adjacent to the slice of Fig. 13.4A) of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver demonstrating a thick gallbladder wall and what appears to be one or two stones (arrow) within the gallbladder (K, kidneys; L, liver; G, gallbladder; Sp, spleen). (C) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the gallbladder (long on gallbladder) of the patient with the gallbladder stones in Figs. 13.4A and 13.4B (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). The ultrasound image (ultrasound is more sensitive at detecting stones than CT) demonstrates numerous stones filling the gallbladder (arrows), which cause shadowing. The CT has underestimated the amount of stones, which in this case are numerous and are impacting the gallbladder (L, liver; GB, gallbladder). (D) Grayscale ultrasound image of the gallbladder (transverse on gallbladder) of the patient with the gallbladder stones in Figs. 13.4A, 13.4B, and 13.4C (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). The ultrasound image (ultrasound is more sensitive at detecting stones than CT) demonstrates numerous stones filling the gallbladder (arrows), which cause shadowing. The CT has underestimated the amount of stones, which in this case are numerous and are impacting the gallbladder (L, Liver). (E) Doppler ultrasound image of the hepatic hilum of the patient in Figs. 13.4A–13.4D (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). The ultrasound image demonstrate the common bile duct (between arrows), which measures 4.7 mm in diameter anterior to the hepatic artery (HA). The Doppler “box” is between the arrowheads (L, liver). Look for access routes (access planning) (Figs. 13.5, 13.6, 13.7, and 13.8) Fig. 13.5 Transperitoneal and transhepatic accesses into the gallbladder. (A) Unenhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver. The dashed line indicates the access trajectory going along the long axis of the gallbladder through a direct transperitoneal approach, through the gallbladder fundus, and without transgressing the liver. (B) Unenhanced axial CT image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver. The dashed line indicates the access trajectory transgressing a small part of the liver and entering the gallbladder at the lateral one-third of its wall. This access is transhepatic; however, it most likely is also transperitoneal because it does not pass through the bare area of the gallbladder. (C) Unenhanced axial CT image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver. The dashed line indicates the transhepatic access trajectory transgressing the liver and entering the gallbladder at the medial one-third of its wall. This access is transhepatic, and most likely (but not definitely) passes through the bare area of the gallbladder. Fig. 13.6 (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver. The dashed line indicates the access trajectory going along the long axis of the gallbladder through a transperitoneal approach, through the gallbladder fundus, and possibly “grazing” the liver. (B) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver. The dashed line indicates the transhepatic access trajectory transgressing the liver and entering the gallbladder at the medial one-third of its wall. This access is transhepatic, and most likely (but not definitely) passes through the bare area of the gallbladder. (C) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image of the abdomen at the lower aspect of the liver. The dashed line indicates the access trajectory to the gallbladder through a direct transperitoneal approach, through the gallbladder fundus, and without transgressing the liver. Fig. 13.7 Computed tomography (CT) images demonstrating proximity of structures to the gallbladder fundus. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image of the abdomen below the liver. The fundus of the gallbladder (G) is surrounded by colon (C). Whenever contemplating transperitoneal gallbladder fundus access, the colon is usually in close proximity. (B) Contrast-enhanced coronal CT reconstruction of the patient in Fig. 13.7A. The solid line indicates the transperitoneal access trajectory entering the gallbladder along its long axis. Again, noted is the close proximity of bowel to the gallbladder fundus (Ht, heart; L, liver; AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; UB, urinary bladder). (C) Contrast-enhanced sagittal CT reconstruction of the patient in Fig. 13.7A. Again, noted is the close proximity of bowel to the gallbladder fundus (G; L, liver; C, colon). Fig. 13.8 (A) Unenhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen below the liver (soft tissue window). The fundus of the gallbladder (G) is surrounded by colon (C). Whenever contemplating transperitoneal gallbladder fundus access, the colon is usually in close proximity (L, liver; K, kidney). (B) Unenhanced axial CT image of the abdomen below the liver (bone window). The fundus of the gallbladder (G) is surrounded by colon (C). Whenever contemplating transperitoneal gallbladder fundus access, the colon is usually in close proximity (L, liver; K, kidney). Look for adjacent organs that can be inadvertently traversed (Figs. 13.7 and 13.8) Fig. 13.9 (A) Hepatobiliary scan over 60 minutes without morphine administration. There is prompt uptake of the radiotracer at time-zero. At 10 minutes, radiotracer is excreted into the intrahepatic biliary tract. Radiotracer is seen in the small bowel from 25–60 minutes. The gallbladder is not visualized in the entire series (arrows). (B) Hepatobiliary scan after administering morphine. Again, the gallbladder is not visualized in the entire series (arrows). These findings are consistent with cholecystitis.

Indications

Gallbladder Indications (More Common Indications)

Bile Duct Indications (Less Common Indications)

Contraindications

Relative Contraindication

Preprocedural Evaluation

Evaluate Prior Cross-Sectional Imaging

Evaluate Prior Hepatobiliary Nuclear Scan

Evaluate Preprocedure Laboratory Values

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree