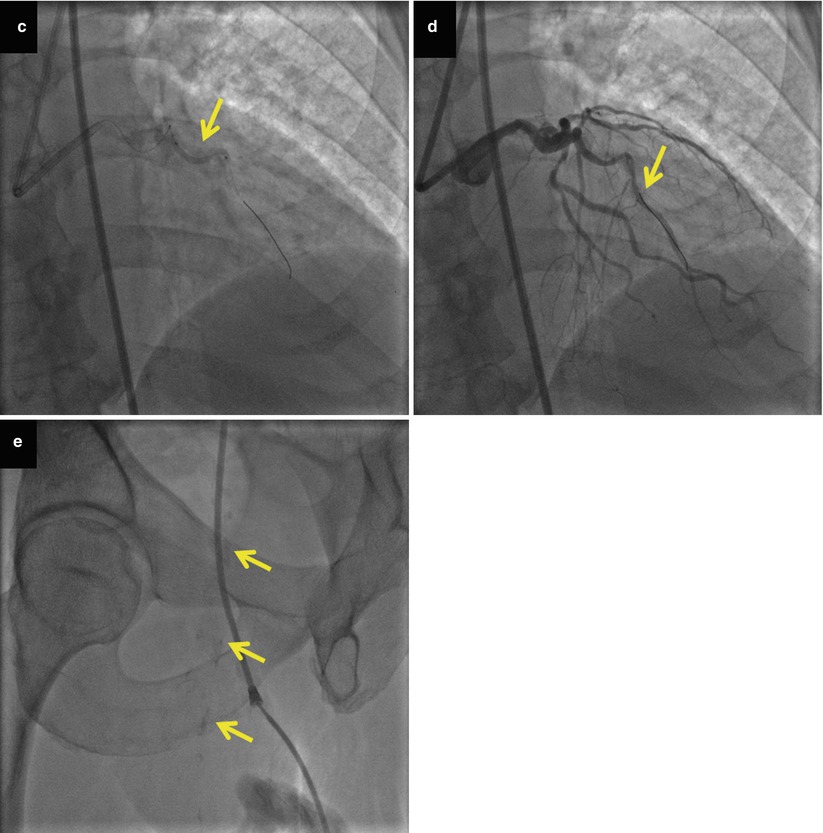

Fig. 19.1

Illustrative case of multivessel disease, calcification, and tortuosity in an 83-year-old man presenting with acute ST segment elevation anterior myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography demonstrating 100 % occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery (arrow, panel a) and of the mid-left anterior descending artery (arrow, panel b), as well as diffuse disease in the circumflex artery (panel b). The left anterior descending artery was wired with difficulty due to marked tortuosity and calcification, and balloon angioplasty was performed (arrow, panel c), resulting in restoration of antegrade flow (panel d). Severe calcification was also presenting the right common femoral artery (arrows, panel e)

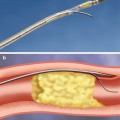

More extensive and complex coronary artery disease: elderly patients often have multivessel disease, multiple lesions, tortuosity and calcification (Fig. 19.2), and chronic total occlusions and often have had prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery [8].

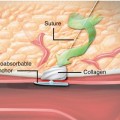

Fig. 19.2

Pathophysiology of increased risk associated with percutaneous coronary interventions in elderly patients

Vascular endothelial changes, with reduced nitric oxide production and prostacyclin synthesis.

Decrease in circulating endothelial progenitor cells [13].

High frequency of myocardial disease, due prior myocardial infarction, hypertension, or other causes.

Multiple comorbidities, such as peripheral arterial disease, renal disease, chronic lung disease, anemia, and frailty. Frailty is characterized by vulnerability to acute stressors and is a consequence of decline in overall function and physiologic reserves and is estimated to be present in 30 % of octogenarians [14].

Altered hemostasis: elderly patients have increased coagulation factors levels and increased platelet reactivity [15].

Decrease in lean body mass and increase in adipose tissue.

Impaired drug metabolism that may frequently lead to medication overdosing. Among non-ST segment elevation ACS patients in the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines), National Quality Improvement Initiative Registry patients aged ≥75 years or older were more likely to receive excess doses of antithrombotic agents compared with patients younger than 65 years (16.5 % vs. 12.5 % for low molecular weight heparin, 38.4 % vs. 28.7 % for unfractionated heparin, and 64.5 % vs. 8.5 % for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) [16]. Those receiving excess doses had higher risk for bleeding (15 % of all bleeding events were attributed to excess dosing) [16].

Careful attention to modifiable risk factors, such as polypharmacy medication dosage adjustment based on the patients’ renal function and comorbidities, is important for optimizing the PCI outcomes in elderly patients.

Technical Aspects

Vascular Access

Older patients are more likely to develop vascular complications for various reasons [19]. First, female gender is the predominant gender among older age groups, and women are known to have higher risk for vascular access complications. Second, peripheral vasculature is thickened and has increased stiffness, in part due to chronic hypertension, which is also very prevalent in this age group. Third, peripheral vessels are often calcified, predisposing to dissection, and fourth there is reduced nitric oxide production predisposing patients to vasoconstriction.

A major advantage of the radial over the femoral access is the very low risk of bleeding and vascular access complications, which is particularly important among elderly patients. In a series of 323 patients aged ≥70 years, radial access was successful in 98.8 % of the patients, and the cannulation and total procedural time were similar to those of patients <70 years old. Only one access bleeding (0.4 %) occurred in the elderly patient group [20]. Similar results were observed in a series of 103 octogenarians undergoing left main PCI [21]. In the largest transradial vs. transfemoral comparative trial performed to date, the RadIal Vs femorAL access for coronary intervention (RIVAL) trial, patients aged ≥75 years with acute coronary syndromes had similarly favorable outcomes using the radial approach with patients <75 years old [1]. The radial approach may also be used for performing coronary angiography and angiography in anticoagulated patients safely, without needing to discontinue warfarin [22].

Use of the radial artery in the elderly also has limitations: (1) advancing the catheters to the coronary ostia may be challenging due to subclavian artery tortuosity [20] but may be assisted by use of hydrophilic 0.035 in. guidewires and having the patient take deep breaths during wire and catheter advancement; (2) guide catheter support is less than that offered by the femoral approach, especially in patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery who need saphenous vein graft interventions [23]; (3) similarly large (such as 8 French) guide catheter may not be used with the radial approach, providing fewer options for treating complex lesions, such as bifurcations; and (4) there is more radiation exposure for the patient and the operator, although the patients may not have long enough life expectancy to manifest complications (such as cancer) due to radiation exposure.

In summary, the radial approach is appealing for PCI in elderly patients due to improved safety profile. Using the left radial artery may be advantageous compared to the right radial artery in the elderly: in a recent randomized trial, the left radial approach was associated with shorter procedural and fluoroscopy times in patients ≥70 years old [24].

Elective PCI

Elective PCI is one of the few areas in which a dedicated study involving the elderly has been performed. In the Trial of Invasive versus Medical Therapy in the Elderly (TIME), an invasive strategy was compared with an optimized medical strategy among 305 patients aged ≥75 years. All patients had Canadian Cardiac Society (CCS) class II or greater angina, despite being medicated with at least 2 antianginal drugs. Coronary revascularization was performed in 74 % of the invasive group patients vs. 37 % of the optimized medical strategy group patients. Six months post enrollment angina severity decreased and measures of quality of life increased in both treatment groups, but these improvements were significantly greater in the revascularization group [25]. Major adverse cardiac events occurred in 72 (49 %) of patients in the medical group and 29 (19 %) in the invasive group (p < 0.0001) [25]. The benefit with the invasive strategy persisted after 4 years of follow-up [26].

In the Alberta Provincial Project for Outcomes Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease (APPROACH) cohort, adjusted 4-year mortality rates for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), PCI, and medical therapy in patients 70–79 years of age ranged between 13 and 21 % and in patients ≥80 years of age, from 23 % for CABG surgery, to 28 % for PCI, and to 40 % for medical therapy [27]. More importantly, quality of life improved to a similar or higher extent with coronary revascularization among patients aged 70–79 years and ≥80 years compared to patients aged <70 years [28].

The more contemporary Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial proved that PCI did not reduce the risk of death, nonfatal MI, and hospitalization for ACS in patients with stable angina compared to optimal medical therapy alone, in patients <65 years old or in patients ≥65 years old [29]. However PCI improved the quality of life more than medical therapy [30], which may be the more important than prolongation of life for elderly patients, especially for the “old old” (>80 years old) patients [1]. In a study of 624 ACS patients undergoing PCI, elderly patients experienced the most improvement in physical health compared to younger patients [31].

Given the complex coronary anatomy often found in elderly patients, PCI of the most important culprit lesion rather than complete revascularization may provide the most favorable risk/benefit ratio.

PCI in Acute Coronary Syndromes

Primary PCI is preferred to thrombolytic administration in elderly patients presenting with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction, in part because of the high intracranial hemorrhage rates with thrombolytic administration in elderly patients [32]. The largest prospective trial of primary PCI vs. thrombolytics is the Senior Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI) study (presented at the 2005 Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics conference, Washington DC), enrolled 481 patients aged ≥70 years. The composite endpoint of death, reinfarction, and stroke was reduced by 55 % (p = 0.009), but no difference was observed among patients aged ≥80 years. In the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE), a 38 % relative decrease in adjusted mortality (p = 0.03) was observed with primary PCI among patients ≥70 years old, although most elderly patients did not receive any reperfusion therapy [33]. In a meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials comparing primary PCI with fibrinolysis, a similar relative mortality reduction favoring primary PCI was observed in all age strata (except in patients ≤50 years of age) [34]. Moreover, due to higher risk of older patients, the absolute risk reduction was strongly and positively associated with age: at age 60 years, primary PCI was associated with 1.4 fewer deaths/100 patients treated compared with fibrinolytic therapy, whereas the risk reduction amounted to 5.1/100 patients at age 80 years [34]. In the Thrombolysis Versus Primary Angioplasty for AMI in Elderly Patients (TRIANA) trial (NCT00257309), primary PCI reduced recurrent ischemia compared to thrombolysis (0.8 % vs. 9.7 %, p < 0.001) in patients over 75 years of age.

Elderly patients presenting with non-ST segment elevation ACS appear to have improved outcomes with an early invasive approach. In the Treat Angina with Aggrastat and Determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TACTICS–TIMI) 18 trial compared to an early conservative strategy, an early invasive strategy provided greater absolute reduction in the composite of death or myocardial infarction with increasing age: 1.5 % among patients 55–65 years old, 2.5 % among patients >65–75 years old, and 10.8 % among patients >75 years old [10]. However, major bleeding rates were higher with an early invasive strategy in patients older than 75 years of age (16.6 % vs. 6.5 %, p = 0.009) [10]. Similar results were seen in the German Acute Coronary Syndromes Registry [35].

In summary primary PCI is the preferred mode of reperfusion for elderly STEMI patients, and an early invasive strategy is preferred for elderly with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes, with careful attention to antithrombotic regimens utilized to minimize the risk of bleeding (discussed in the Adjunctive Pharmacotherapy section below).

Multivessel Disease, Tortuosity, and Calcification

Elderly are more likely to have multivessel disease, which increases the complexity of coronary revascularization. Moreover, their coronary vessels are more likely to have tortuosity and calcification.

Calcification and tortuosity (Fig. 19.2) are associated with significantly increased technical difficulty and risk, related to equipment delivery to the target lesion and to optimal stent expansion. Careful lesion preparation by predilation and/or use of rotational atherectomy may be needed to facilitate stent delivery [36] and minimize the risk for stent loss [37]. Post-stenting invasive imaging with intravascular ultrasonography or optical coherence tomography is also important to ascertain adequate procedural result and minimize the risk for subsequent complications.

Drug-Eluting vs. Bare-Metal Stents

Although there are no randomized controlled trials comparing bare-metal stents (BMS) with drug-eluting stents (DES) specifically in elderly patients, observational studies have shown encouraging results with lower mortality and repeat revascularization rates with DES [38, 39]. A meta-analysis of five randomized trials of paclitaxel-eluting stents showed that compared to patients receiving BMS, patients receiving paclitaxel DES aged >70 years had comparable rates of death, myocardial infarction, and stent thrombosis but a significantly lower target lesion revascularization rate (22.2 vs. 10.2, P < 0.001) [40]. Moreover, although the mortality rate of patients aged >70 years was higher than those of younger patients, it was comparable with age- and gender-matched norms in the general population [40]. Therefore, DES can be utilized in older patients, provided they can receive at least 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Prior Coronary Bypass Graft Surgery

Elderly patients in need for PCI are more likely to have prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, which increases their risk for subsequent events [41]. Although most PCIs are still performed on native coronary artery lesions in prior CABG patients, the proportion of interventions performed in saphenous vein grafts increases with increasing time interval from CABG [42]. Saphenous vein graft PCI carries high risk for periprocedural myocardial infarction (usually due to distal embolization) and in-stent restenosis. The risk of myocardial infarction can be reduced by using embolic protection devices (EPDs), which have a class I indication for use in SVGs “when technically feasible” in both American [43] and European [6] guidelines. However, EPDs are currently used in only 22–23 % of SVG interventions in the USA [44, 45]. Although there have been conflicting results on the benefit of DES in SVG lesions in early studies [46–49], in the largest trial performed to date (ISAR-CABG [50]), DES use was associated with lower need for repeat revascularization with similar incidence of death and myocardial infarction compared to BMS. DES are currently utilized in the majority of SVG PCI in the USA [45].

Left Main

Treatment of left main disease remains controversial with CABG recommended for most patients in the USA. However, based on the promising results of the Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial that showed similar outcomes at 1 year post PCI or CABG for left main disease [51], in the European coronary revascularization guidelines, left main PCI carries a class IIa indication for isolated left main or left main and one-vessel disease, IIb indication for left main with 2- or 3-vessel disease, and SYNTAX score ≤32 but class III indication for left main with 2- or 3-vessel disease and SYNTAX score ≥33 [6]. Considering the potentially higher rate of perioperative complications with CABG in elderly patients, PCI may be particularly useful in elderly patients with left main disease and high surgical risk. A retrospective analysis of 259 elderly patients (≥75 years old) with unprotected left main coronary artery disease demonstrated similar incidence of death and myocardial infarction but higher need for repeat revascularization among patients treated with DES compared to those treated with CABG [52]. However, more studies such as the ongoing Evaluation of Xience Prime versus Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery for Effectiveness of Left Main Revascularization trial (EXCEL, NCT01205776), in which the outcomes of PCI with a second-generation drug-eluting stent are compared with those of CABG in patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis, are needed to allow for better decisions on the risks and benefits associated with left main stenting.

Adjunctive Pharmacotherapy

Periprocedural Antithrombotic Therapy

Elderly patients have higher risk of bleeding compared to younger patients. This is related to several factors, such as decreased drug metabolism, overdosing, and higher susceptibility to bleeding for anatomic reasons, such as peripheral arterial tortuosity and calcification.

Apart from use of the radial access, bleeding may be reduced by use of less aggressive anticoagulant and antiplatelet regimens. In the Randomized Evaluation in PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events (REPLACE) 2 trial, patients >75 years old had lower mortality with bivalirudin compared to heparin + glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors [53]. Similarly, in the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy (ACUITY) trial, non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients aged ≥75 years undergoing PCI had similar incidence of ischemic events but higher risk of bleeding compared to younger patients. The risk of non-CABG-related bleeding was 6.1 % with bivalirudin vs. 12.3 % with heparin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (number needed to treat = 16) [54].

Compared to younger patients, the administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in elderly patients carries decreased efficacy and increased bleeding risk: in a meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors that included 31,402 patients, those who were ≥70 years old (35 % of the overall patient population) had a nonsignificant 4 % relative reduction in the 30-day risk of death or myocardial infarction but had 62 % increase in major bleeding [55].

In summary, bivalirudin use may reduce the bleeding risk among elderly patients undergoing PCI without decreased efficacy in preventing ischemic events. When more aggressive antiplatelet therapy is needed, such as administration of glycoprotein IIb/inhibitors for cases of large coronary thrombus, careful attention should be paid to avoid overdosing (by careful measurement of patient’s weight and creatinine clearance) and minimize the risk for bleeding [16].

Post-procedural Antithrombotic Therapy

The preferred antiplatelet therapy post PCI in elderly patients is low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1

Outcomes among elderly patients in contemporary studies of antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes

Study | Description | Elderly patients | Efficacy endpoint for elderly | Bleeding overall/elderly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ISAR-REACT-2 [55] | Non-ST segment elevation ACS | 40 % > 70 year | Abciximab 10.9 % UFH 9.9 % | 1.4 % vs. 1.4 %/2.7 % vs. 1.9 % |

Early ACS [56] | Non-ST segment elevation ACS | 25 % > 75 year | Eptifibatide Early 11.4 % Late 11.4 % | 2.6 % vs. 1.8 %/not reported |

ACUITY [53] | Non-ST segment elevation ACS | 18 % > 75 year | Bivalidurin 11.7 % UFH/GPI 9.6 % | 3.0 % vs. 5.7 %/5.8 % vs. 10.1 % |

CURE [57] | Non-ST segment elevation ACS | 49 % > 65 year | Clopidogrel 13.3 % Placebo 15.3 % | 3.7 % vs. 2.7 %/not reported |

TRITON-TIMI 38 [58

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|