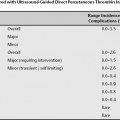

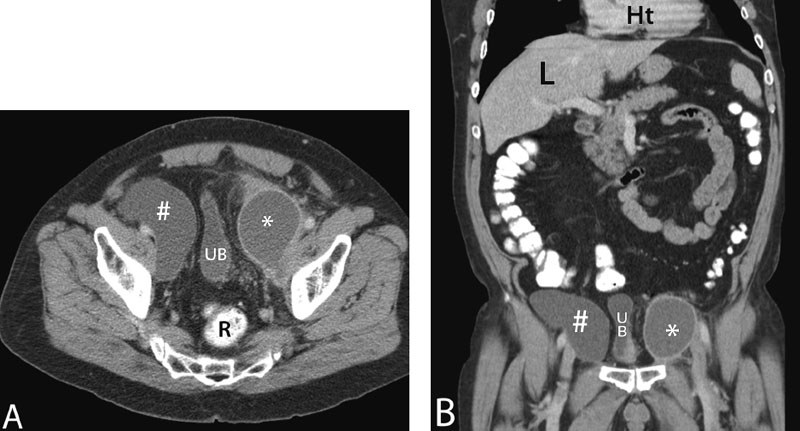

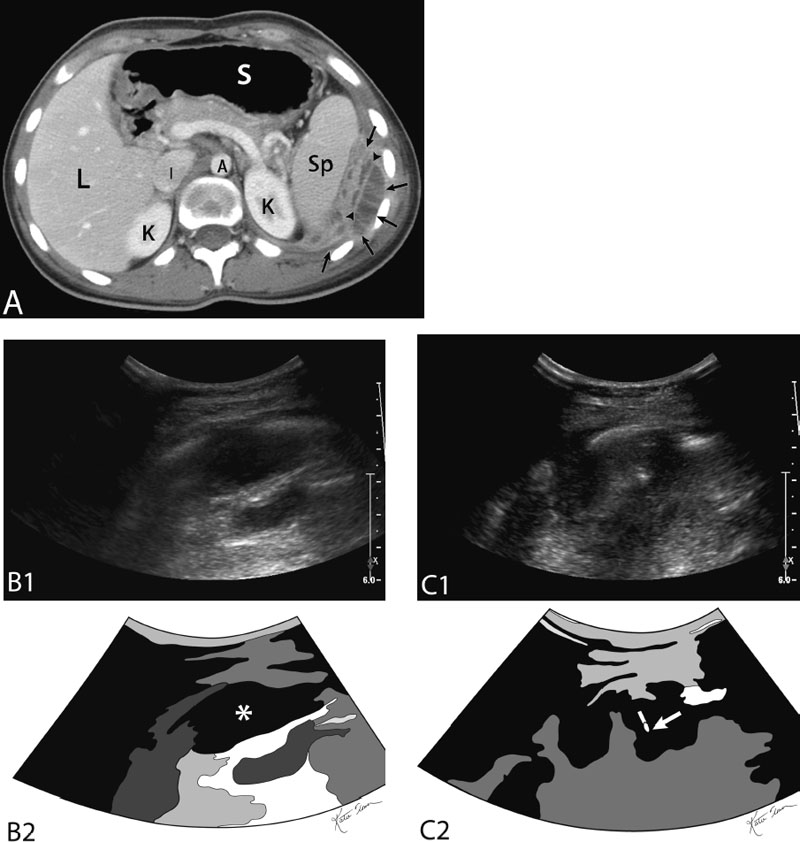

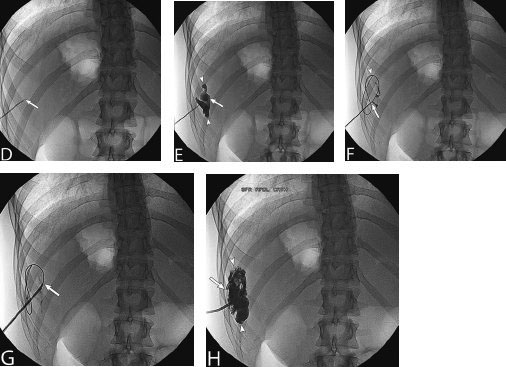

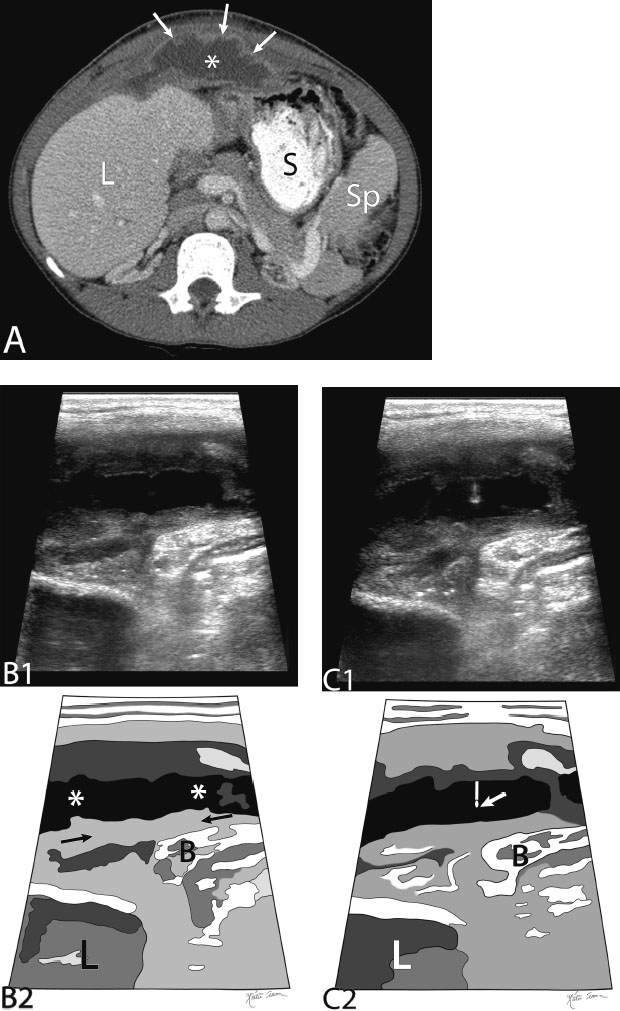

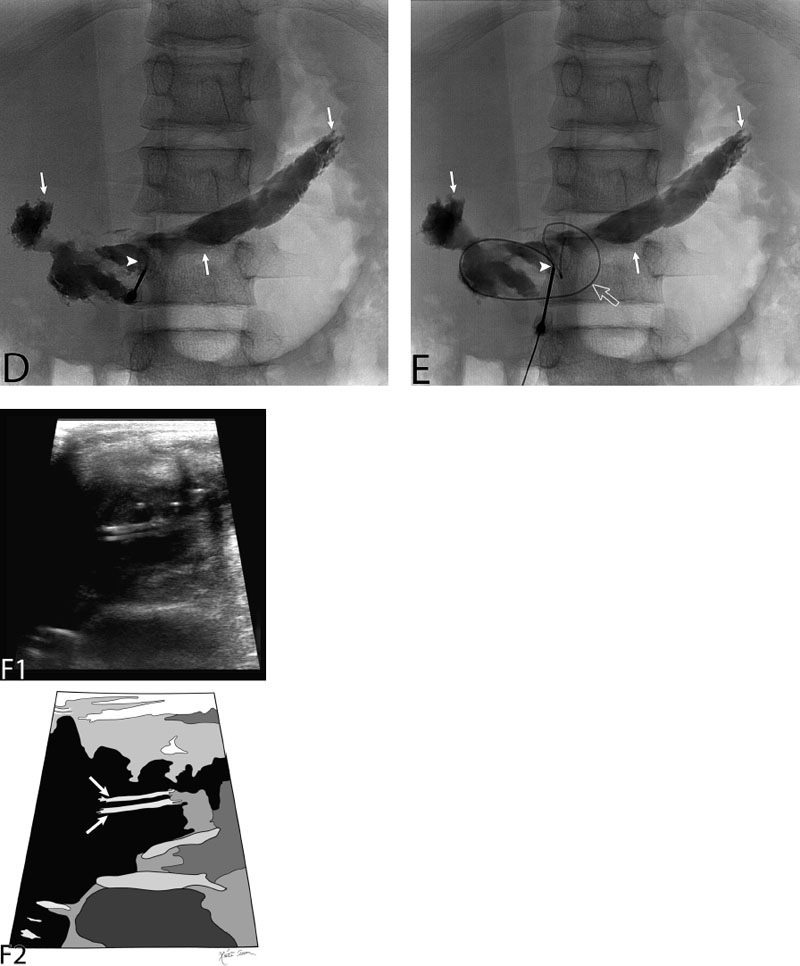

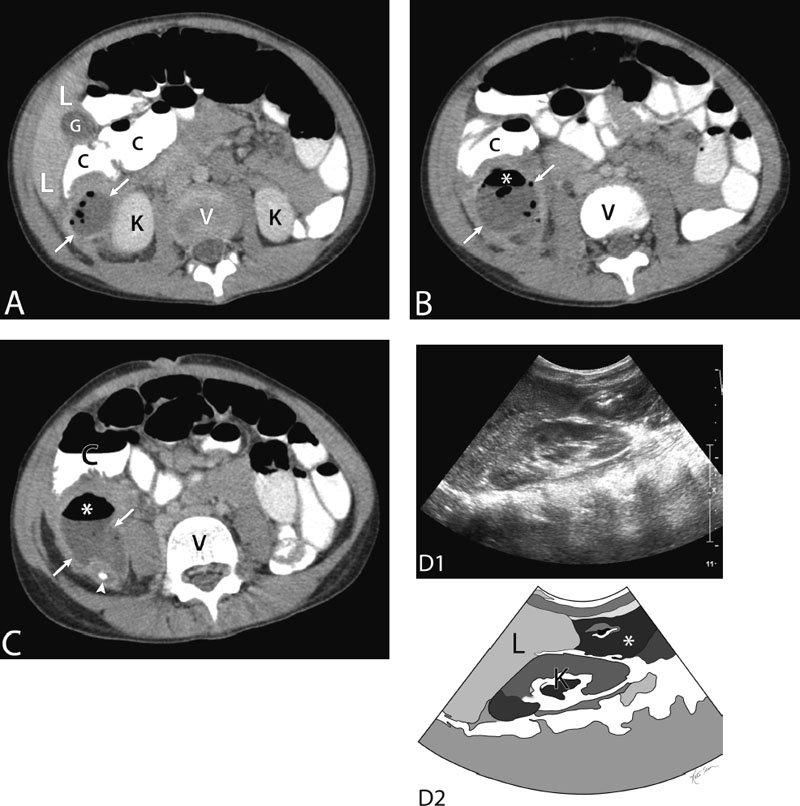

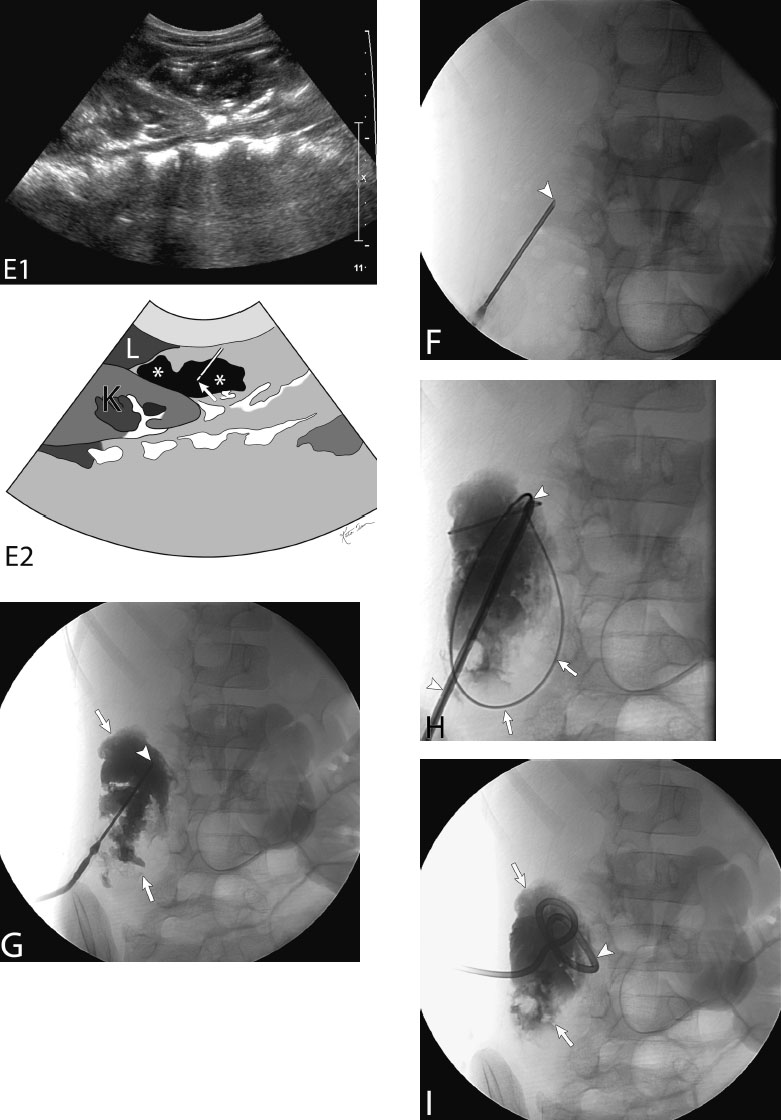

15 Percutaneous Drainage of Fluid Collection Fluid collections can be classified in many ways. Extravisceral abdominal fluid collection drainage is the primary focus in this chapter. There are minor variations to what is described here when it comes to other types of fluid collections. The following are indications of percutaneous drainage of fluid collections: Fig. 15.1 Bilateral pelvic lymphoceles with pressure symptoms on the urinary bladder. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the midpelvis of a patient status postradical prostatectomy demonstrating bilateral pelvic fluid collections (* and #). These collections compress the centrally located urinary bladder (UB). The patient was complaining of urgency and frequency in micturating. No compression is appreciated on the rectum (R). These collections, given the clinical history and location, are most likely postoperative lymphoceles as a result of pelvic lymphatic injury and postoperative lymph leakage collecting as lymphoceles. Of note, the right-sided collection (#) has less of a perceptible wall with less stranding around it. The left-sided collection (*) has a thicker enhancing wall with stranding of the surrounding pelvic fat. If one of these lymphoceles is infected the likelihood is that the left-sided collection (lymphocele) is more likely to be infected. (B) Coronal reconstruction of the contrast-enhanced CT study of Fig. 15.1A. Again noted are the bilateral pelvic fluid collections (* and #) which are most likely lymphoceles. These collections compress the centrally located urinary bladder (UB). The patient was complaining of urgency and frequency in micturating. The left-sided collection (*) has a thicker enhancing wall with stranding of the surrounding pelvic fat. If one of these lymphoceles is infected the likelihood is that the left-sided collection (lymphocele) is more likely to be infected. Remember that thick enhancing walls are not definite evidence of infection especially in the setting of postoperative collections such as hematomas or lymphoceles (L, liver; Ht, heart). When consulting to drain postoperative or posttraumatic hematomas, one must use caution. The clinical indication (symptomatology) directs whether to place a drain or not. This is because solid hematomas do not drain well and require large drains that dwell for extended periods. In addition, a hematoma may not be infected; however, the indwelling drain may introduce an infection (skin or nosocomial fungal and/or bacterial seeding) and convert a benign hematoma into an abscess. The indications for percutaneously accessing (aspiration or drain placement) a hematoma are as follows: Fig. 15.2 Drain placement of a left-sided chest wall abscess. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen demonstrating a thick enhancing walled abscess (arrows). The abscess is multiloculated and septated. A clear septum is seen (between arrowheads). The abscess is extrapleural and extraperitoneal (K, kidney; L, liver; A, aorta; I, IVC; S, stomach). (B) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess in the patient depicted in Fig. 15.2A (top) and a schematic sketch of it (bottom). The abscess is seen (* in epicenter of abscess). The collection is not clearly hypoechoic because of the thick pus and turbid nature of its contents and the numerous fibrin septations with it. (C) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess in the patient despicted in Figs. 15.2A and 15.2B (top) and a schematic sketch of it (bottom). An 18-gauge needle has been passed into it (arrow at needle tip). (D) Fluoroscopic image with the 18-gauge access needle (arrow at needle tip) in position within the main locule of the abscess. This was confirmed by ultrasound (Fig. 15.2C). (E) Fluoroscopic image after injecting contrast through the 18-gauge access needle (arrow at needle tip). Contrast is seen to fill the abscess (between arrowheads). This confirms the findings by CT. The operator should correlate the size, orientation, and location of what is seen by fluoroscopy with the collection on the preprocedural CT. This confirms adequate placement of the collection. (F) Fluoroscopic image after passing a 0.035-inch wire (arrowhead) through the 18-gauge access needle (arrow at needle tip) and coiling it inside the collection (arrowhead). Injecting contrast and coiling a wire inside the abscess helps break locules and ultimately helps drainage of the fluid collection/abscess. (G) Fluoroscopic image after passing an 8-French drain over the 0.035-inch wire. The drain has an inner metal stiffener, which supports the drain as it is passed through the tissues. The drain is passed over the wire and beyond the metal stiffener just beyond the point marked by the arrow. (H) Fluoroscopic image after injecting contrast through the 8-French drain, which has been coiled in the collection (arrow at tip of drain). The contrast fills the collection (between the arrowheads). Fig. 15.3 Drain placement of a central anterior abdominal wall abscess. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen demonstrating a thick irregular enhancing walled abscess (arrows). The center of the abscess is marked by the asterisk (L, liver; Sp, spleen; S, stomach). (B) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess in the patient depicted in Fig. 15.3A (top) and a schematic sketch of it (bottom). The abscess is seen (* in abscess) superficial to the peritoneum (between arrows). Just deep to the peritoneal plane is echogenic gas-filled bowel (B) and deeper yet the liver (L). (C) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess in the patient depicted in Figs. 15.3A and 15.3B (top) and a schematic sketch of it (bottom). An 18-gauge access needle has been passed into the collection (arrow at needle tip). At this time in the procedure, the procedure is converted to real-time fluoroscopic guidance (B, bowel; L, liver). (D) Fluoroscopic image after injecting contrast through the 18-gauge access needle (arrowhead at needle tip). Contrast is seen to fill the abscess (arrows). This confirms the findings by CT. The operator should correlate the size, orientation, and location of what is seen by fluoroscopy with the collection on the preprocedural CT (Fig. 15.3A). This confirms adequate placement of the collection. (E) Fluoroscopic image after passing a 0.035-inch wire (hollow arrow) through the 18-gauge access needle (arrowhead at needle tip) and coiling it inside the collection (arrows). Injecting contrast and coiling a wire inside the abscess helps break locules and ultimately helps drainage of the fluid collection/abscess. (F) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess after a 10-French drain was placed (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). The tubular structure between the arrows is the 10-French drain. This image is not necessary for the procedure. Confirmation of drain placement should have been already confirmed by fluoroscopy. Fig. 15.4 Drain placement of a right paracolic appendiceal abscess. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography (CT) image of the lower abdomen of a child demonstrating a right paracolic abscess (between arrows) with air within it. The abscess is due to a ruptured appendix (L, liver; G, gallbladder; C, colon; K, kidney; V, vertebra [intervertebral disk]). (B) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image of the lower abdomen demonstrating a right paracolic abscess (between arrows) with air within it (*) (C, colon; V, vertebra). (C) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image of the lower abdomen demonstrating a right paracolic abscess (between arrows) with air within it (*). An appendicolith is seen adjacent to the abscess (C, colon; V, vertebra). (D) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess in the patient depicted in Figs. 15.4A–15.4C (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). The abscess is seen (* in abscess) superficial to the kidney (K) and inferior to the right hepatic lobe (L, liver). (E) Gray-scale ultrasound image of the abscess (*) in the patient depicted in Figs. 15.4A–15.4D (top) and schematic sketch of it (bottom). An 18-gauge access needle has been passed into the collection (arrow at needle tip). At this point in the procedure, the procedure is converted into fluoroscopic guidance (K, kidney; L, liver). (F) Fluoroscopic image with the 18-gauge access needle (arrowhead at needle tip) in the collection. This is confirmed by ultrasound in Fig.15.4E and by injecting contrast under fluoroscopy. (G) Fluoroscopic image after injecting contrast through the 18-gauge access needle (arrowhead at needle tip). Contrast is seen to fill the abscess (arrows). This confirms the findings by CT. The operator should correlate the size, orientation, and location of what is seen by fluoroscopy with the collection on the preprocedural CT (Figs. 15.4A–15.4C). This confirms adequate placement of the collection. (H) Fluoroscopic image after passing a 0.035-inch wire (arrows) through the 18-gauge access needle and coiling it inside the collection (arrows). A 10-French drain (between arrowheads) with an inner metal stiffener is being advanced over the wire. (I) Fluoroscopic image after injecting contrast through the 10-French drain, which has been coiled in the collection (arrowhead). The contrast fills the collection (between the arrows).

Classification

Indications

Contraindications

Relative Contraindication

Absolute Contraindication

Preprocedural Evaluation

Evaluate Prior Cross-Sectional Imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree