Penetrating trauma

Blunt traumatic rupture of the duodenum

Pelvic trauma with perforation of the rectum

Postoperative

Post-diagnostic procedure

Spontaneous colon perforation

Extension from pneumomediastinum

Gas-containing retroperitoneal abscess

Duodenal perforation is an acute illness whose major causes are peptic ulcer disease, endoscopic complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or sphincterotomy, and blunt abdominal trauma [2].

Perforation of the duodenum caused by blunt trauma to the abdomen is now being encountered as an automobile lap belt deceleration injury. In duodenal injuries, mural hematoma, laceration, or complete transection of the duodenum is usually encountered, attributable to the following mechanisms: (1) tearing during deceleration, (2) crushing between the abdominal wall and the spine, and (3) blowout [3].

Rupture usually occurs at the junction of the second and third portions, which are retroperitoneal, resulting in a local accumulation of gas in the right perirenal or anterior pararenal space; multiple perforations are possible, and there may be accompanying traumatic pancreatitis. Duodenal perforation may also be secondary to leukemia and penetrating foreign body. Severe pelvic fractures, dislodging bony fragments, can perforate the rectum, allowing intestinal gas to migrate into the retroperitoneal spaces. Rectal perforations can also result from iatrogenic procedures, infection, or colorectal cancer. Self-induced colorectal perforations are rare and can result from foreign body or accidental impalement. Distinction between injuries to the intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal segments of the rectum is an important consideration in patients with rectal injury given the differences in their subsequent management. The anterior and lateral sidewalls of the upper two-thirds of the rectum are covered with peritoneum, and injuries to these segments are considered intraperitoneal. The distal one-third of the rectum circumferentially and the upper two-thirds of the rectum posteriorly are not covered with peritoneum and are considered extraperitoneal [4].

Spontaneous pneumoretroperitoneum is commonly a consequence of perforations of colonic diverticula or carcinomas. The thorax and the extraperitoneal spaces communicate directly through the mediastinum posteriorly and, to a lesser extent, across small midline openings in the diaphragm anteriorly. Thus, any cause of pneumomediastinum may also determine the presence of pneumoretroperitoneum.

Other causes of pneumoretroperitoneum include superinfected necrotizing pancreatitis, necrotizing fasciitis, abscess formation, percutaneous biopsy, epidural anesthesia, extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy, and hydrogen peroxide wound irrigation [1].

Pneumoretroperitoneum following endoscopic procedures is extensive, however, because of the high pressure gradient generated and the large volume of air insufflated; it is thus sometimes associated with pneumoperitoneum and pneumothorax [5]. Pneumoretroperitoneum can be also a possible finding of bowel infarction [6].

12.3 Pneumoretroperitoneum: Plain Abdominal Film and CT Findings

Conventional radiography is commonly the initial imaging examination performed in the diagnostic workup of patients who present with acute abdominal pain to the emergency department.

Conventional radiography includes supine and upright conventional abdominal radiography and upright chest radiography [7]. On plain film, beneath the diaphragm, it is often difficult to differentiate retroperitoneal from intraperitoneal air: retroperitoneal air is usually crescentic, with curvilinear upper and lower borders. Free air rises to the peak of the diaphragmatic dome, whereas retroperitoneal air is usually positioned more inferiorly. Retroperitoneal air generally accumulates either medially or laterally rather than directly beneath the apex of the diaphragmatic leaf [8].

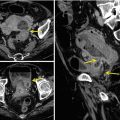

Supine abdominal radiographs can show areas of mottled air or collection of air in the left or right upper quadrant (Fig. 12.1), indicating pneumoretroperitoneum, with lack of left psoas muscle shadow, suggesting potentially retroperitoneal illness [9]. Similar findings can be observed on scout CT images (Fig. 12.2).

Fig. 12.1

Supine abdominal radiography showing retroperitoneal air (arrow) dissecting around the right kidney

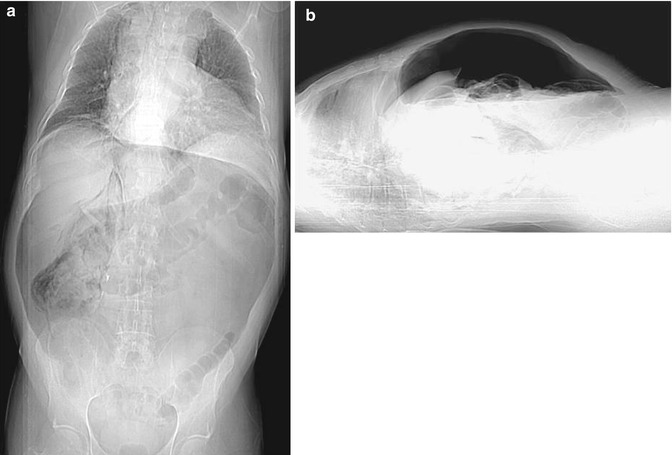

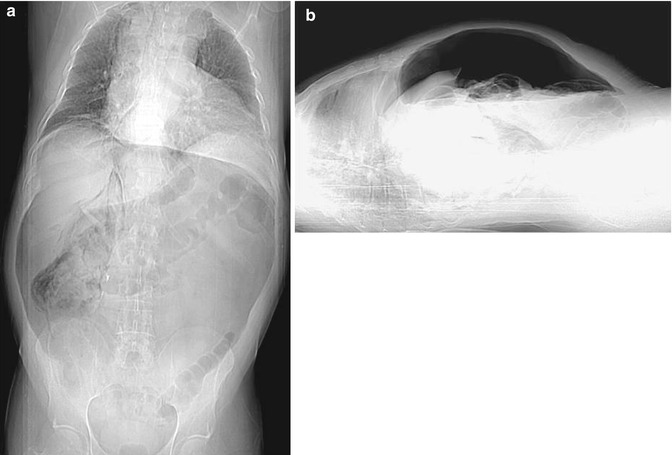

Fig. 12.2

Scout CT images (a, AP view; b, lateral view) demonstrating the presence of pneumoperitoneum and retropneumoperitoneum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree