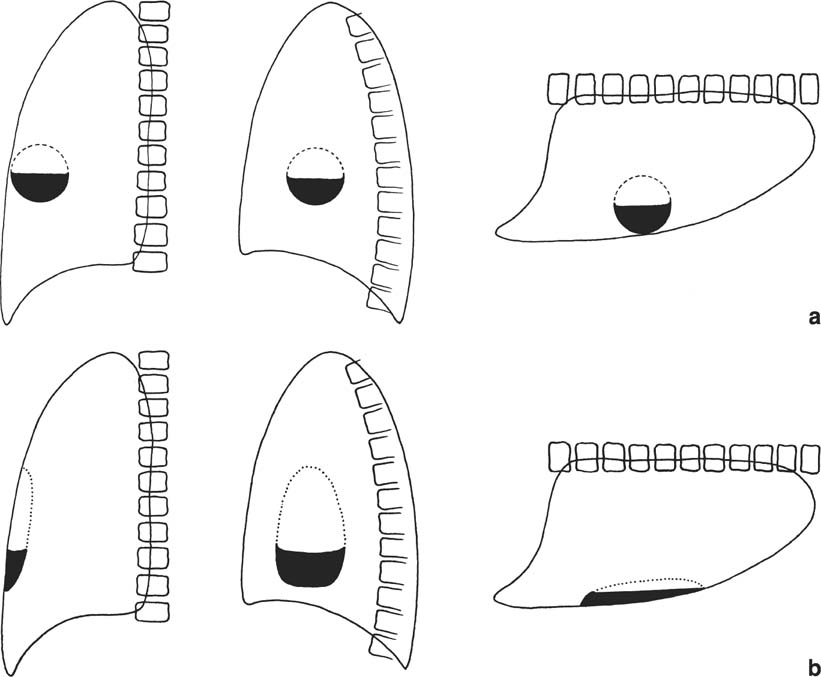

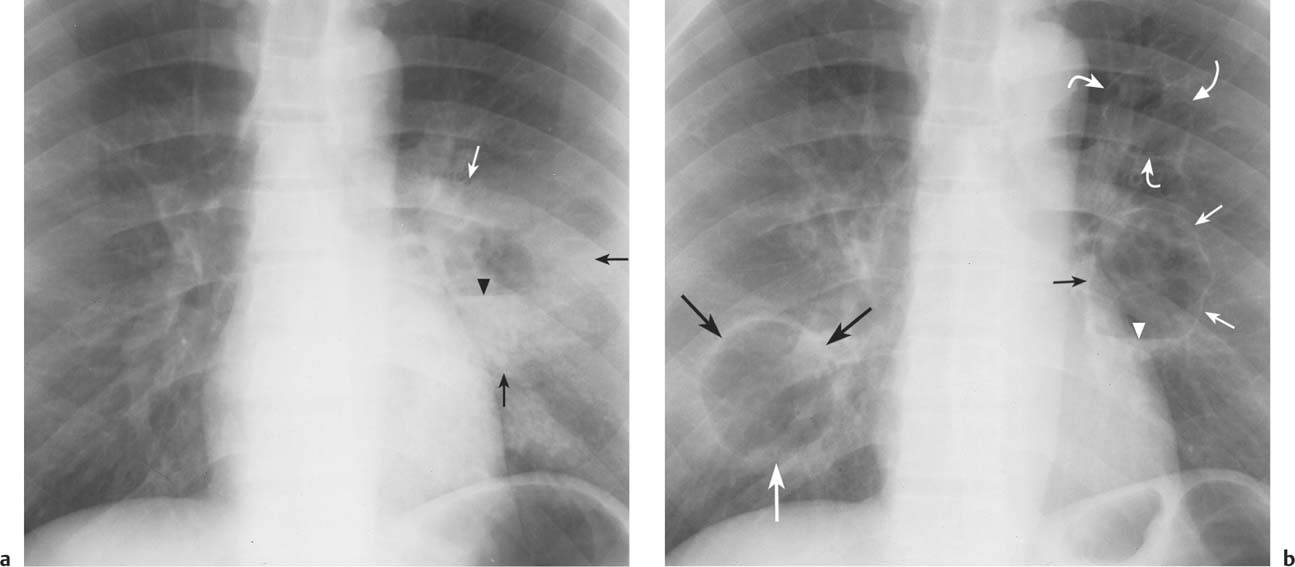

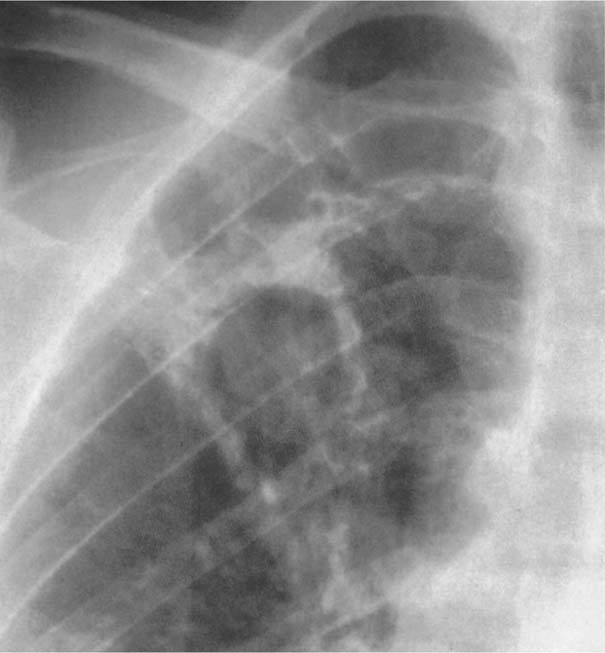

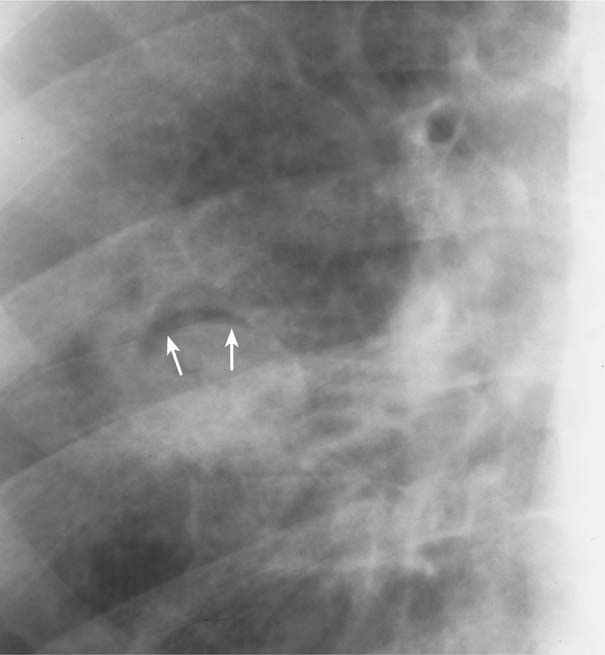

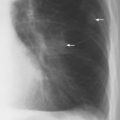

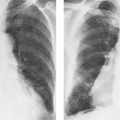

9 Pulmonary Cavitary and Cystic Lesions Pulmonary cavitary and cystic lesions are characterized by their central air content. Cavities usually result from central necrosis within a lesion and the subsequent expulsion of the necrotic material into the bronchial system. Rupture of a fluid-filled cyst or infection of a bulla may produce a similar radiographic appearance. Cavities often contain fluid that appears as an air-fluid level on radiographs performed with horizontal beam. Air-fluid levels occur when a lesion with a liquid content ruptures into the tracheobronchial system and part of its content is expelled, or when both gas and pus are produced by bacteria. A cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level is, however, not pathognomonic of a pulmonary lesion (e.g., a lung abscess), but also can be encountered in the event of a loculated hydropneumothorax (e.g., loculated empyema secondary to the bronchopleural fistula). Radiologic differentiation of these two entities is, however, made possible by the fact that a pulmonary cavity tends to be spherical and, consequently, the length of the air-fluid level is very similar on frontal, lateral, and decubitus films. A loculated hydropneumothorax, however, is virtually never spherical, since it must conform in shape to the adjacent chest wall and, consequently, the length of the air-fluid level varies widely between different projections (Fig. 9.1). Cystic lesions can be mimicked by plastic (radiolucent) spheres inserted in the past into the extrapleural space to collapse the adjacent lung for the treatment of tuberculosis. Since these spheres were often not water-tight, small amounts of fluid could collect in them, mimicking small air-fluid levels on upright films. Nowadays, cystic lesions with or without air-fluid levels can be simulated by both hiatal and diaphragmatic hernias (congenital or posttraumatic), when they contain the stomach or loops of bowel. Characteristic of these hernias is, however, a considerable change in the size and shape of the lesions between subsequent radiographs. Cavitary lesions can be differentiated from each other by their size, location, wall thickness, number and by the nature of both their inner lining (smooth or irregular) and content (fluid versus mass). The cavity wall thickness can be described as hairline (1 mm or less), thin (2 to 4 mm) and thick (5 mm and more) (Fig. 9.2). Hairline cavities are invariably associated with benign conditions such as bullae, blebs and pneumatoceles. The vast majority of thin-walled cavities are also found with a variety of benign lesions including chronic infections such as coccidiodomycosis, whereas thick-walled cavities are equally divided between benign and malignant conditions such as lung abscess, primary and metastatic carcinoma, and Wegener’s granulomatosis. However an extremely thick cavity wall exceeding 15 mm is highly suspicious of a malignant neoplasm. A solitary cavitary lung lesion is frequently found in a pulmonary abscess, a malignant neoplasm or a lung cyst (congenital or posttraumatic). Multiple cavitary lung lesions suggest Wegener’s granulomatosis and septic emboli or metastatic disease. The inner lining of a cavity is usually nodular in a bronchogenic carcinoma, shaggy in an acute lung abscess and smooth in most other lesions. Fluid in the presence of gas can be diagnosed in a cavitary lesion by the demonstration of an air-fluid level on radiographs taken with horizontal beam. The intracavitary fluid may be serous or sanguinous or represent pus or liquefied necrotic tissue. Besides fluid, a mass can also be found within a cavitary lesion. With regard to the size of the cavity, the mass can be quite small or occupy most of the cavitary space. In the latter case, the mass is only separated from the wall of the cavity by a crescent-shaped air space. Most commonly, intracavitary mass lesions represent mycetomas, especially aspergillomas (Figs. 9.3 and 9.4). They can be found in infectious (particularly tuberculous), tumoral, bronchiectatic, and cystic cavities that do not contain any fluid. Similar intracavitary masses can be produced by necrotic tumor fragments in carcinomas, sequestered necrotic lung tissue in klebsiella or, rarely, in pneumococcal pneumonias, a blood clot, or by the collapsed membrane of a ruptured echinococcal cyst floating on top of the fluid (“water-lily” or “camelot” sign). Fig. 9.1 a, b Differentiation between air-fluid levels, a in a peripheral pulmonary cavity and b in a loculated hydropneumothorax. a A pulmonary cavity tends to be spherical and therefore an air-fluid level in such a lesion has the same length in anteroposterior, lateral, and decubitus films. b A loculated hydropneumothorax must conform to the chest wall and is therefore never spherical. The length of the air-fluid level varies considerably between different projections as shown here in the anteroposterior, lateral, and decubitus films. Fig. 9.2 Cavitary lesions with variable wall thickness. a A lung abscess (arrows) presenting as poorly defined thick-walled cavitary lesion with air-fluid (pus) level (arrowhead) is seen in the left lower lobe. b Four years later a pneumatocele with hairline wall (small arrows) and tiny fluid level (arrowhead) has replaced the abscess. A second pneumatocele (curved arrows) is seen more cephalad. A thin-walled cyst (large arrows) representing another healing abscess is now seen in the right lower lobe. Fig. 9.3 Aspergilloma in a tuberculous cavity. A right upper lobe cavity is seen containing a mass lesion. Note also the pericavitary infiltrates indicating still-active tuberculosis. Fig. 9.4 Aspergilloma in old abscess cavity. The aspergilloma is separated from the wall of the cavity by a crescent-shaped air space (arrows). The differential diagnosis of various cavitary and cystic lesions measuring 1 cm or more in diameter is given in Table 9.1.

Disease | Radiographic Findings | Comments |

Bronchogenic cyst (congenital or traumatic) | Solitary thin-walled lesion with or without air-fluid level. | Congenital cysts are characteristically located in medial third of the lungs with lower lobe predilection. |

Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration (Fig. 9.5) | Solitary, unilocular, or multilocular cystic mass that may or may not contain air-fluid levels. Cyst walls are thick or thin. | Lesion is usually contiguous with the diaphragm and characteristically located in a posterobasal segment of a lower lobe (left to right ratio 3:1). Masking of lesion by surrounding pneumonia is possible. |

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (Fig. 9.6 and 24.7) | Multilocular cystic mass with or without air-fluid levels, similar to bronchopulmonary sequestration, but involves at least an entire lobe without predilection. The volume of the affected lung is usually increased or, less commonly, decreased. Three types are differentiated. Type I: Single or multiple large cysts exceeding 20 mm in diameter. DD: Congenital lobar emphysema involving LUL (40%), RML (35%), RUL (20%), or two lobes (5%). Type II: Multiple cysts measuring 5 to 12 mm in diameter. Type III: Solitary large bulky mass with 3 to 5 mm small microcysts. | Involves characteristically one lobe, but occasionally two lobes or both lungs are affected. Usually diagnosed in infancy, but may occasionally be diagnosed first in older children or adolescents. May be part of a wider spectrum that includes also bronchogenic cysts and sequestrations. DD: Diaphragmetic hernia containing bowel loops (Fig. 9.8) and extensive cystic bronchiectases (Fig. 9.9). |

Pulmonary papillomatosis | Multiple, well-defined nodules that frequently cavitate and then resemble cystic bronchiectases. | Most common laryngeal tumor in children, but rare in adults. Pulmonary papillomas seldom develop in the absence of laryngeal or tracheal lesions. |

Bronchogenic carcinoma (Fig. 9.10) | Solitary, usually thick-walled cavity with irregular inner lining. A smooth, thin-walled cavity is a rare presentation. Necrotic tumor tissue may simulate mycetoma. Air-fluid levels are uncommon. | Cavitation occurs in up to 10% of cases of bronchogenic carcinoma, most commonly in squamous cell carcinomas, especially in the upper lobes, and undifferentiated large cell carcinomas, rarely in adenocarcinomas, and never in small cell carcinomas |

Metastases, hematogenous (Fig. 9.11) | Multiple nodules of different sizes with thin or thick-walled cavities developing in a varying percentages of lesions (few to almost all). | Cavitation less common than in bronchogenic carcinoma. Metastases frequently originate from squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (thin-walled cavities), or gynecologic tumors and sarcomas (thick-walled cavities). |

Lymphoma (Fig. 9.12) | One or more consolidations with usually thick-walled cavities that have an irregular inner lining and may contain an air-fluid level. |