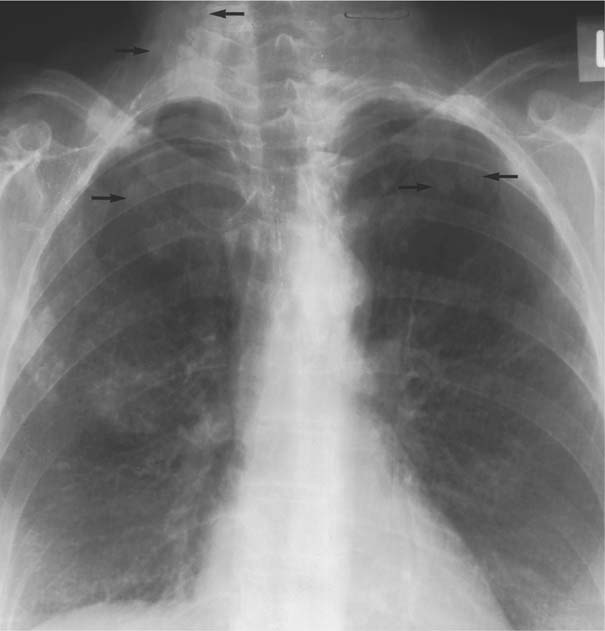

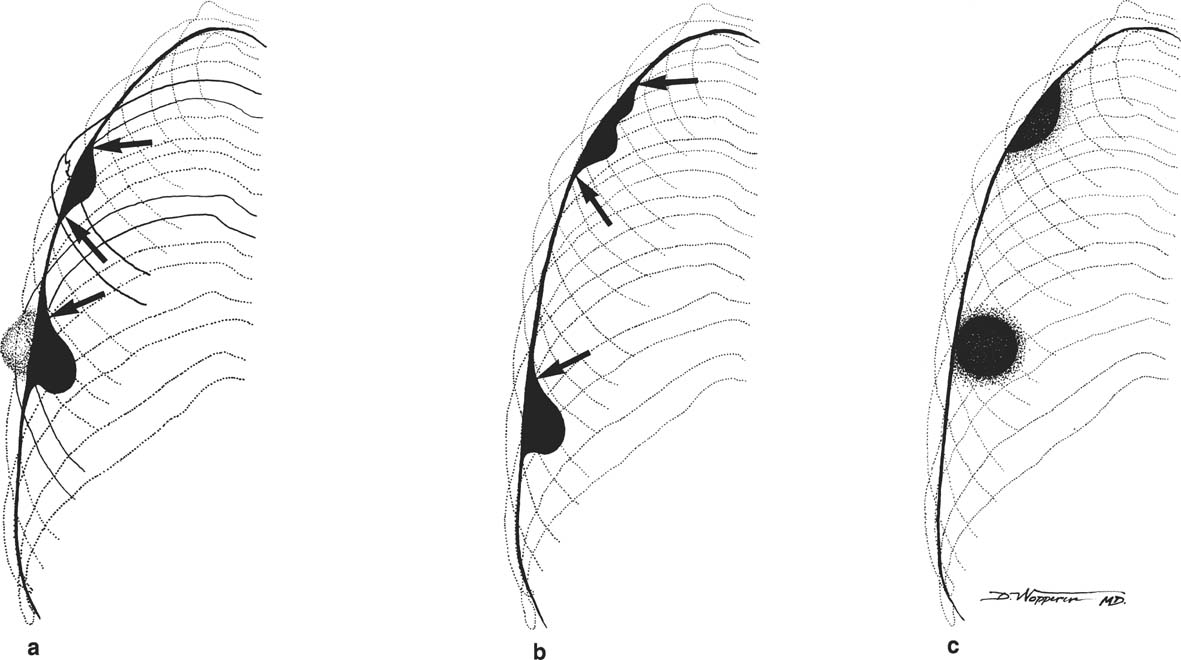

8 Pulmonary Nodules and Mass Lesions A variety of lesions located outside the lung parenchyma can simulate pulmonary nodules and mass lesions. Extrapulmonary lesions projecting into the lung fields and simulating intrapulmonary conditions are either surrounded by air (e.g., skin lesions) or have a density that is significantly greater than that of the surrounding soft tissue. The latter is the case, for example, in calcified and ossified lesions. Nipple shadows frequently simulate pulmonary coin lesions on the frontal chest radiograph but can be differentiated from them easily by repeating the chest radiograph with arms elevated over the head. With the latter technique, it is possible to separate a nipple shadow that by chance was superimposed on a true intrapulmonary nodule. Similarly, skin tumors (e.g., neurofibromas) must be differentiated from intrapulmonary mass lesions (Fig. 8.1 and 8.2). When skin tumors are multiple, some of them are likely to project outside the lung fields, thus facilitating the correct diagnosis. Focal rib lesions can be diagnosed by confirming with oblique views that the lesion cannot be seen separately from the bone in different projections. Cloth and film artifacts must also be excluded. Pleural and extrapleural mass lesions protruding into the lung can be difficult to differentiate from a pulmonary lesion abutting the visceral pleura. When the lesions are seen tangentially, both pleural and extrapleural lesions are said to form an obtuse angle with the chest wall. However, pulmonary mass lesions abutting the pleural surface (e.g., “Hampton’s hump” in pulmonary infarction) may also form an obtuse angle. Furthermore, larger pleural and extrapleural lesions often resemble the shape of a female breast when viewed in profile. In these cases an obtuse angle with the chest wall is found only on the upper margin of the lesion, whereas it becomes acute on its lower end. Pleural and extrapleural lesions, therefore, can be more reliably differentiated from pulmonary lesions by demonstrating a triangular soft-tissue density at the side where the lesion blends into the chest wall (Fig. 8.3). This triangular soft-tissue density is caused by gradual separation of the pleura from the chest wall by the mass lesion. Demonstration of this sign requires viewing the lesion in profile. It cannot be seen when a tumor originates from the visceral pleura and grows exclusively into the lung parenchyma. It might be hidden at the inferior margin of the breast-shaped pleural or extrapleural lesion. Pleural and extrapleural lesions usually have a well-demarcated surface when projected in profile, since they are covered with pleura, whereas pulmonary lesions may have smooth or shaggy margins. Since pleural and extrapleural lesions often have a long, flat appearance, they may only produce a vague and indistinct increase in the lung density when seen en face. Pleural lesions are often lobulated or multiple, whereas extrapleural lesions are often associated with a rib fracture or rib destruction. Mass lesions and loculated pleural effusions within the interlobar fissures must also be differentiated from parenchymal lung lesions. This is usually possible because of the characteristic anatomic location, oblong shape, and well-defined margins of such pleural lesions. When viewed tangentially their ends blend imperceptibly with the corresponding interlobar fissure. Fig. 8.1 Multiple skin nodules in neurofibromatosis simulating intrapulmonary nodules. Multiple nodular lesions (arrows) are seen. Some of them are projecting into the lung fields, while others are clearly outside the lungs. Fig. 8.2 Skin lesion mimicking intrapulmonary nodule. An ovoid density projects into the left lower lung field. Fig. 8.3 Differential diagnosis of a extrapleural, b pleural, and c pulmonary lesions, when seen in profile. a Extrapleural lesions are often associated with rib lesions (fracture or destruction) and lift up the parietal and visceral pleurae from the chest wall, which is evident as a triangular density at the upper and lower margin of the lesion (arrows). b Pleural lesions are often lobulated and also demonstrate the “pleural lift-up sign” at their margins (arrows), unless they originate from the visceral pleura and grow primarily into the lung parenchyma, c Pulmonary lesions abutting the pleural surface do not separate the pleura from the chest wall and may be well or poorly demarcated. An acute angle between a lesion and the chest wall at both its superior and inferior margins is also characteristic of a pulmonary mass. See text for more detailed discussion. The margins of true pulmonary nodules may be smooth, lobulated or spiculated. In general, smooth margins suggest benignity and spiculation malignancy, whereas lobulation is found with approximately equal frequency in benign and malignant lesions. Satellite lesions are defined as small nodular opacities in close proximity to a larger, usually solitary lesion. They usually indicate an infectious etiology such as a tuberculoma. The differential diagnosis of solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules and masses is summarized in Table 8.1, while the differential diagnosis of disseminated pulmonary nodules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter has already been summarized in Table 6.1 of Chapter 6.

Disease | Radiographic Findings | Comments |

Bronchogenic cyst (Fig. 8.4) | Solitary, sharply circumscribed, round mass measuring up to several centimeters in diameter, most commonly in the medial third of the lungs with predilection for lower lobes. Cavitation occurs with infection, resulting in communication with the bronchial system. Calcification of cyst wall and cyst content is very rare. | Approximately two-thirds of bronchogenic cysts are pulmonary and the rest mediastinal in origin. Congenital and acquired (e.g., following lung abscess or trauma) cysts are radiographically indistinguishable from each other. Acquired cysts have no site predilection. |

Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration (Fig. 8.5) | Well-defined, homogeneous mass usually contiguous with the diaphragm and characteristically located in the posterobasal segment of a lower lobe (left to right ratio, 3:1), whereas the upper lobes are rarely affected. Air-fluid levels are seen within the lesion when communication with the bronchial system occurs, usually because of infection. Angiographically, large feeding arteries from the thoracic and/or abdominal aorta are characteristic. Drains to pulmonary veins. | Asymptomatic until sequestered tissue becomes infected. This often occurs only in adulthood, when the anomaly is usually first recognized. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (type III) may also present as large bulky mass (see Fig. 9.7). |

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration (Fig. 8.6) | Well-defined homogeneous mass that is related to the left diaphragm (above or below) in 90% of patients, and in the remaining cases related to the right diaphragm or the mediastinum. Cavitation is rare, since the lesion is enclosed by its own visceral pleura. Blood supply derives from a systemic artery (usually from the abdominal aorta or one of its branches) and drainage occurs via the inferior vena cava, the azygos or hemiazygos system, or the portal vein. | Frequently associated with other more severe congenital anomalies (e.g. diaphragmatic hernias, eventrations and foregut communications), which may result in death during infancy. |

Arteriovenous fistulas (Fig. 8.7) | Solitary or less common, multiple, well-defined round or slightly lobulated lesion(s) measuring up to several centimeters. Change in size and shape with Vasalva and Mueller maneuvers. Predilection for medial third of lungs and lower lobes. Feeding artery and/or draining vein can often be identified as band-like density extending from hilum to lesion. Calcifications (phleboliths) are rarely seen. | Approximately half of the cases are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber disease) with arteriovenous fistulas in the skin, mucous membranes, and other organs. A pulmonary artery branch aneurysm (Fig. 8.8) can also present as a central pulmonary nodular lesion. |

Pulmonary vein varicosity | One to several round, well-defined densities measuring up to a few centimeters in diameter. Characteristic central location, best seen on lateral radiograph projecting posterior and inferior to the hilar structures. Change shape and size with Valsalva and Mueller maneuvers (similar to arteriovenous fistulas). | Congenital or acquired tortuosity and dilatation of a pulmonary vein just before its entrance into the left atrium. |

Twenty percent present as solitary, well-circumscribed and often slightly lobulated peripheral lung lesions measuring usually 1 to 3 cm (occasionally up to 10 cm) in diameter. Calcifications/ossifications are rarely visible on chest radiographs, but may be identified on CT in about 30% of cases. Eighty percent are centrally located in the bronchial lumen presenting with segmental or lobar atelectasis and obstructive pneumonia. Cavitation is extremely rare. Hilar, mediastinal and bony metastases (lytic and/or blastic) are occasionally associated. | Locally invasive, low-grade malignant tumors with tendency for recurrence and occasional metastases to extrathoracic sites. Four types: carcinoid (90%), cylindroma (6%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (3%) and pleomorphic adenoma (1%). Age ranges from 12 to 60 years (mean age 35 to 45 years) without sex predilection, but very rare in blacks. Clinical manifestations include hemoptysis (50%), atypical asthma, persistent cough and recurrent obstructive pneumonia. | |

Solitary, well-circumscribed, and often lobulated lesion in the lung periphery measuring up to 4 cm in diameter. Calcifications occur in less than 10% of cases and are virtually diagnostic when they resemble popcorn (multiple punctate calcifications throughout the lesion). Rarely, radiolucent areas (fat) can be seen within the lesion. | Peak incidence in the sixth decade (similar to bronchogenic carcinoma) with only 6% occurring in patients under 30. “Multiple pulmonary fibroleiomyomatous hamartomas” can be considered a related condition that is extremely rare. | |

Papilloma | Solitary, or more commonly multiple, well-defined nodules that frequently cavitate. When they are centrally located in the bronchial lumen, they may present as segmental atelectatis and obstructive pneumonitis. | Most common laryngeal tumor in children, but rare in adults. Bronchopulmonary papillomas develop only rarely in the absence of laryngeal or tracheal lesions. |

Mesenchymal tumors (e.g., leiomyoma, lipoma, hemangioma, teratoma, chemodectoma, and neurogenic tumors) | Rare, usually solitary, well-defined lesions. | Except for hemoptysis in hemangiomas, these lesions are in the majority of cases asymptomatic. Malignant counterparts of these mesenchymal tumors may very rarely also originate in the lung, but represent usually hematogenous metastases from a sarcoma located in another organ. |

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (alveolar cell carcinoma) (Fig. 8.13) | Local form (75%). Well-circumscribed focal mass in peripheral/subpleural location, often associated with linear strands (“rabbit ears” or “tail sign”) extending from the lesion to the pleura (desmoplastic reaction). Larger lesions (> 4 cm) may become ill-defined with spiculated margins (“sunburst” appearance). Tumor may surround aerated bronchus (“open bronchus sign”). The earliest stage may present with ground-glass haziness and bubble-like hyperlucencies (pseudocavitation) caused by dilatation of intact airspace from desmoplastic reaction. Diffuse form (25%) presents as airspace consolidation with air bronchograms and poorly marginated borders or multiple bilateral poorly or well-defined nodules. Pleural effusions are associated in 10% of cases. | Considered to be a variant of bronchogenic adenocarcinoma with mucinous (80%) and nonmucinous (20%) subtypes. Occurs in patients between 40 and 70 years of age without sex predilection. May be asymptomatic or presenting with cough (50%), shortness of breath (15%), weight loss (12%), hemoptysis (10%) and/or fever (8%). Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|