Keigo Osuga

Pushable coils have been widely used for mechanical occlusion of peripheral and visceral vessels because they are relatively inexpensive, easily available, and simple to handle. Since the original stainless steel coils were developed in the mid-1970s,1 refinements have been made in the materials and designs used for pushable coils, including the recent addition of hydrogel coating technology.2 Similarly, detachable microcoils, although they are expensive, have been also increasingly indicated in peripheral vessels because they can be repositioned and offer more precise coil deployment. However, pushable coils still remain the standard tool for indications requiring mechanical embolic agents and can save both cost and procedure time.

DEVICE DESCRIPTION

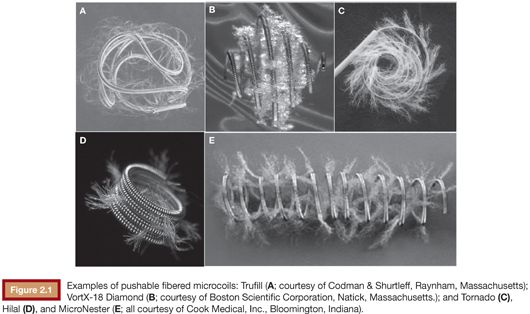

Pushable fibered coils are composed of metallic springs with inert synthetic fibers, such as polyester or nylon, attached to the spring to induce thrombosis around the coil. Pushable coils are supplied in a straight cartridge and are typically loaded into the catheter using a guidewire or the provided mandrel. The loop sizes, lengths, thickness, and configurations vary among pushable coil designs (Fig. 2.1). Two major options are 0.035-in coils for delivery through 4-Fr to 5-Fr catheters and 0.018-in microcoils for delivery through microcatheters for more selective embolization.3 Platinum coils are softer and more radiopaque than stainless steel or Inconel alloy coils. Because stainless steel is responsible for severe local artifacts on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, MR conditional coils made of platinum and Inconel alloy are currently preferred. Long pushable platinum coils or microcoils with an extended lengths are pliable and pack easily into a dense coil mass.4 Most recently, hydrogel-coated pushable coils (AZUR Pushable 35 and 18; Terumo Medical Corporation, Somerset, New Jersey) have become available, and they have the advantage of greater filling volume, independent of thrombus formation.2

TECHNIQUE

As a rule, the coil delivery process should be carefully monitored under fluoroscopy. The coil should be appropriately sized according to the vessel size and anatomy. The first coil should be approximately 20% larger in size than the vessel diameter to minimize the risk of coil migration. The delivery catheter should be accurately positioned within the target vessel. The coaxial technique, using a guide catheter and a coaxial delivery catheter, gives stability and control for coil deployment. A standard catheter can also serve as a guide catheter to deploy microcoils through a microcatheter. There are two methods for delivery of pushable coils. The first method is the “push” technique, in which the coil is pushed by a floppy guidewire or designated pusher wire. The other method is the “flush” technique, in which the coil is forced out of the catheter by saline flush. Although this technique can speed up the delivery process, it should be avoided when precise coil placement is critical and when coil dislodgement is a concern, especially for the first or last coil.

Clinical Application

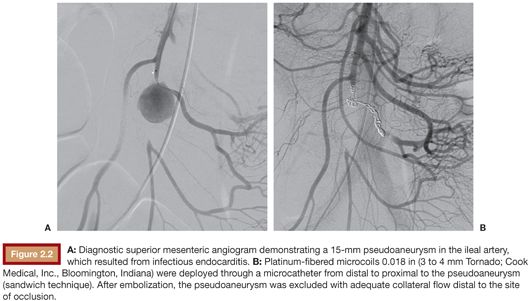

Pushable coils are mechanical embolic agents used both in arteries and veins for various indications: to control bleeding; to occlude vascular lesions such as aneurysms, varices, and arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs); and to redistribute blood flow to protect nontarget vessels. The details for each indication will be described in later chapters. In general, to occlude a terminal artery that is unlikely to have associated collateral circulation, coils are simply pushed out at, or just before, the site to be occluded. In a larger vessel, proximal coil occlusion may allow persistent flow distal to the site of occlusion via collaterals but at a lower pressure than before embolization. For example, proximal splenic artery embolization is an accepted technique in the setting of traumatic splenic injury to control bleeding. If significant retrograde filling of an embolized vessel(s) is likely via collaterals, the sandwich technique is effective; that is, coils should be placed both proximal and distal to arterial pathology such as a wide-necked aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 2.2). Proximal coil embolization is not effective for arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), as it not only results in persistent flow to the nidus of the AVM via collaterals but also sacrifices the main arterial access for subsequent interventions. For pulmonary AVMs, pushable coils are often used to occlude the distal feeding artery as close to the venous sac as possible.5 Finally, for the purpose of protective embolization, the right gastric and gastroduodenal arteries are often occluded with coils before liver-directed therapy such as arterial infusion chemotherapy or radioembolization for liver tumors.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree