CHAPTER 41 Pyogens, Mycobacteria, and Fungus

SYPHILIS AND NOCARDIA INFECTIONS

Neurosyphilis

Epidemiology

After infection with T. pallidum about one third of patients with syphilis develop tertiary syphilis. One to 3 percent of AIDS patients present with neurosyphilis.1

Clinical Presentation

Neurosyphilis can occur weeks to decades after the initial infection. Most often it is asymptomatic. Symptomatic neurosyphilis may present in four forms: (1) meningovascular syphilis, (2) gummatous neurosyphilis, (3) paretic neurosyphilis, and (4) tabes dorsalis. Headache and focal neurologic deficits are characteristics of meningovascular neurosyphilis complicated by cerebral infarction. Personality changes, psychiatric symptoms, memory loss, and speech disturbances are typical for general paresis and diffuse parenchymal involvement. Neurosyphilis has an accelerated course in the AIDS population.1

Pathophysiology

In meningovascular syphilis the leptomeninges show thickening and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates. The intracranial vessels show evidence of vasculitis that leads to stenoses and occlusions with ischemia and infarction. In one series, 23% of patients with syphilis showed evidence of cerebral infarctions.2 In a second series, 43% of patients had cerebral infarction.3 The infarctions primarily involved the basal ganglia, the middle cerebral artery territory, and branches of the basilar artery.4 Large arteries show concentric or asymmetric stenoses. These may manifest as segmental constriction and occlusion of the supraclinoid carotid arteries.5 Small arteries show focal stenosis and aneurysmal dilatations.

Pathology

Microscopic features of parenchymatous neurosyphilis include degenerative neuronal changes, gliosis, and scattered microglia.6 Gummas are well-defined masses of granulation tissue surrounded by mononuclear epithelial and fibroblastic cells.

The arteries most commonly affected by meningovascular neurolues are the middle cerebral artery and branches of the basilar artery.5

Imaging

MRI

Meningovascular syphilis causes cerebral infarctions in 43% of patients.3 Acute infarctions appear as zones of restricted diffusion with high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values. Subacute and chronic infarctions appear as high signal lesions on T2-weighted (T2W) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. MR angiography shows the narrowing or occlusions of the vessels. Nonspecific focal or diffuse enhancement observed on enhanced MR images cannot distinguish meningovascular syphilis from meningitis of other origin.

In gummatous neurolues, gummas are usually hyperdense on CT and hyperintense on T2W MR images. On contrast-enhanced MRI, cortically located ring- or nodular-enhancing lesions with adjacent meningeal enhancement should raise suspicion of a possible syphilitic gumma.7

Nocardiosis

Nocardiosis is a bacterial infection caused by weakly grampositive, filamentous Nocardia species.

Epidemiology

Most cases of nocardiosis occur as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients. Nocardial infection is seen in less than 5% of renal transplant recipients. Fewer than 2% (0.3%-1.8%) of all infections in AIDS patients are due to Nocardia.8 Fifty percent of patients with systemic nocardiosis have central nervous system (CNS) involvement.

Pathophysiology

Nocardia is a genus of gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria. N. asteroides is responsible for approximately 80% of CNS nocardial infections.9 Other pathogenic species include N. farcinica, N. brasiliensis, N. transvalensis, and N. otitidis-caviarum. Nocardia usually establishes a primary infection in the lung and spreads hematogenously to the CNS in 15% to 44% of cases. In one study of 30 Nocardia infections in HIV-positive patients, 73% of patients had pulmonary disease.8 Solitary brain abscess is the most common form of CNS infection with Nocardia, but multiple lesions are found in about 38% of cases.

Imaging

CT

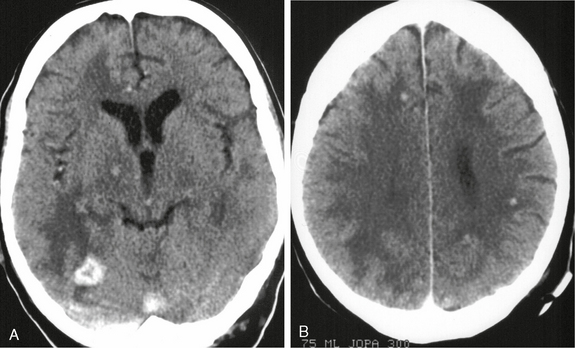

Contrast-enhanced CT usually shows multiple or multiloculated ring-enhancing lesions with perifocal edema and mass effect (Fig. 41-1).11

MRI

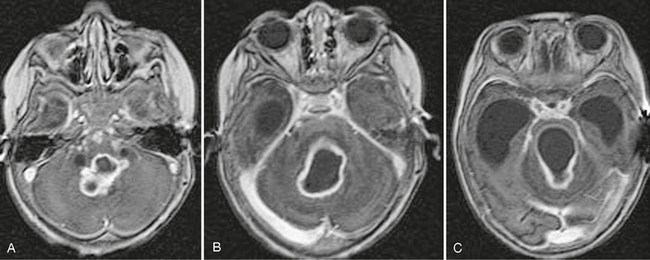

The MR appearance of a nocardial abscess is similar to that of other pyogenic brain abscesses. The necrotic center is hyperintense on T2W imaging and hypointense on T1-weighted (T1W) imaging. The capsule has high T1 signal and low T2 signal and shows smooth peripheral enhancement on contrast-enhanced images. Nocardial CNS infection may also manifest as subependymal nodules and meningitis.11 In one study, 92% of AIDS patients with nocardial CNS infection had imaging evidence of associated meningeal disease.11 Of the nine patients, hydrocephalus was present in five, subependymal nodules were evident in five, and clinical evidence of meningitis occurred in three. Histologic examination of the small subependymal nodules revealed inflammatory cells consistent with ventriculitis/ependymitis and developing subependymal abscesses.11 Nocardial abscesses may assume a characteristic “budding” appearance in which multiple, closely spaced, hematogenously disseminated abscesses conglomerate to create a budding appearance as they enlarge.12 Diffusion-weighted images can show homogeneous hyperintensity within the lesion (Fig. 41-2). In limited case material of active nocardiosis, MR spectroscopy showed a rise in the mean choline/creatine ratio and a slight reduction in the mean Nacetyl-aspartate (NAA)/creatine ratio, with lactate and amino acid peaks consistent with bacterial abscess.13

FIGURE 41-2 Nocardia brain abscess in an immunocompetent woman. A, Axial FLAIR-TSE MRI (TR/TE/TI 7385/130/2100) shows a high signal intensity lesion in the left occipital cortex. B and C, High signal on DWI and low ADC value suggested a bacterial abscess. Biopsy, aspiration of the lesion cavity, and isolation of the organism confirmed the infection with Nocardia.

CNS TUBERCULOSIS

Epidemiology

AIDS is considered the main risk factor for the development of tuberculosis.14 In 2006 the percentage of tuberculosis cases known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was 12.4% and the percentage of cases of tuberculosis with unknown HIV status was 31.7%. CNS involvement occurs in 2% to 5% of all tuberculosis patients and in up to 15% of AIDS patients.15 It is known that tuberculosis may appear in the early stages of immunodeficiency and that the clinical manifestations, management, and epidemiology are altered in AIDS patients.

Clinical Presentation

Calvarial Tuberculosis

Calvarial tuberculosis usually presents as a painless scalp swelling (Pott’s puffy tumor). Involvement of the outer table and scalp may lead to a draining sinus. Neurologic deficits are uncommon. In one series of 42 cases of calvarial tuberculosis, the average duration of symptoms was 2.5 months.16

Pathophysiology

1. Initially small tuberculous lesions (Rich’s foci) develop in the meninges, the subpial or the subependymal surfaces of the brain or the spinal cord. These may remain dormant for years after initial infection.

2. Subsequent growth or rupture of one or more of these small tuberculous lesions causes the diverse forms of CNS tuberculosis. Rupture into the subarachnoid space or into the ventricular system results in meningitis.

Tuberculous meningitis is characterized by thick gelatinous exudates, which favor the meninges at the base of the brain. Tuberculous inflammation (vasculitis) of the vessels that traverse the subarachnoid space causes narrowing, occlusions of the vessels, and subsequent infarctions, usually affecting the middle cerebral artery territory and the small perforating arteries that supply the basal ganglia.17 The meningeal involvement impairs cerebrospinal fluid flow and resorption, so communicating hydrocephalus is the most common complication of meningeal tuberculosis.18 Villoria and colleagues report hydrocephalus in 51% of 35 patients with AIDS-related CNS tuberculosis.19

Tuberculous granulomas (tuberculomas) result from the hematogenous spread of infection or from the extension of meningitis into the parenchyma. Tuberculomas may be solitary or multiple, can occur anywhere in the brain, but are found predominantly in the supratentorial compartment.19

Tuberculous abscess is a true pyogenic lesion.

Focal tuberculous cerebritis is a rare form of tuberculosis.

Pathology

In tuberculosis, thick, gelatinous exudates will be present in the basal cisterns. Tuberculomas are firm, avascular, spherical granulomatous masses measuring 2 to 8 cm in diameter. They are well demarcated from the surrounding brain tissue, which is compressed around the lesion and shows edema and gliosis.

Imaging

Tuberculous Meningitis

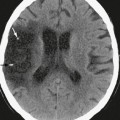

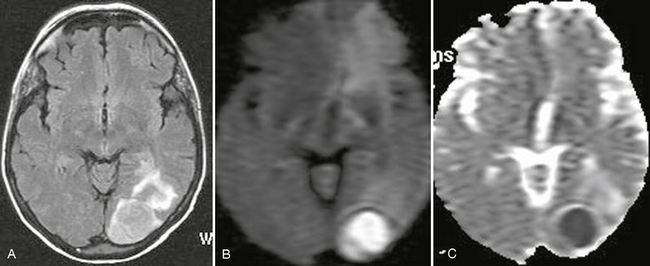

Contrast-enhanced CT typically shows thick intensely enhancing basilar exudates. MRI shows such exudates at the base and over the convexity in 36% to 61% of cases (Fig. 41-3).19–21 CT demonstrates infarcts in 20.5% to 38% of cases (Fig. 41-4), but MRI shows a significantly higher incidence. DWI helps to detect early infarcts. MR angiography helps to show tuberculous vascular pathology (see Fig. 41-4).17 In the majority of patients, CT and MRI both show hydrocephalus as ventricular enlargement and ependymitis with abnormal enhancement of the ventricular ependyma (see Fig. 41-3). Enhancement of nerves indicates their involvement by tuberculosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree