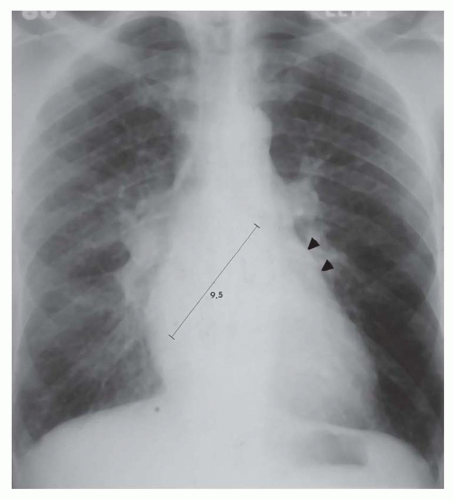

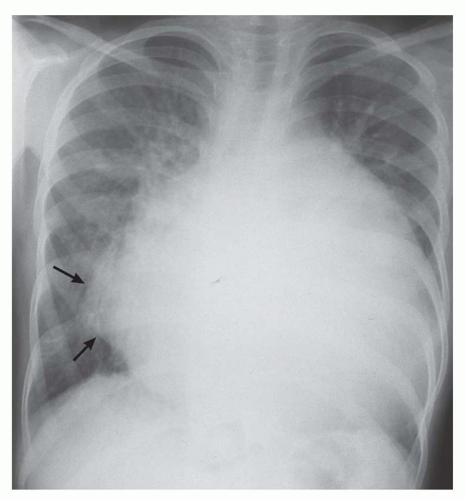

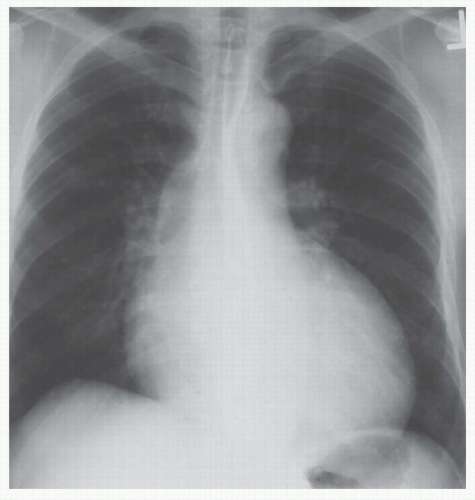

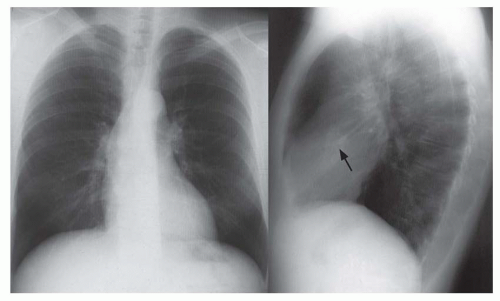

of abnormality is usually PVH. The major signs of PVH are equalization or larger diameter of the upper compared to the lower lobe vessels; loss of prominence or clear visualization of the right lower lobe pulmonary artery; prominence of the interstitial markings, especially the appearance of Kerley A and B lines; indistinctness of the pulmonary vascular margins and/or hilar vessels; loss of the right hilar angle; and alveolar filling (Figs. 30-3,30-4,3-5 and 30-6). After repeated episodes of pulmonary edema in longstanding cases of mitral valve disease, permanent interstitial lines or ossific nodules may appear. Ossific nodules are small foci of bony metaplasia that appear in the lungs only after multiple episodes of edema and chronic PVH. Foci of hemosiderin may form fibrotic nodules in patients with multiple episodes of edema as well as after multiple episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage.

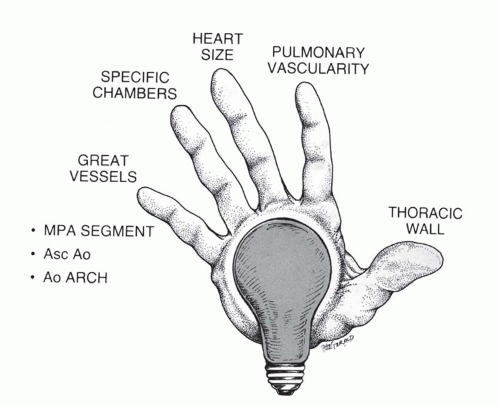

FIG. 30.2. Diagnostic pathway for the identification of the hemodynamically predominant cardiac lesion. Signposts gleaned from the thoracic radiograph guide the analysis. |

TABLE 30.1 Radiographic Classification of Acquired Heart Disease | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

pulmonary edema; Table 30-2). The pulmonary venous pressure (or mean left atrial wedge pressure) associated with edema varies depending on whether the cardiac dysfunction is acute or chronic (Table 30-3). The venous pressure in chronic disease is approximately 5 mm Hg greater for each grade of PVH compared to that in acute disease.

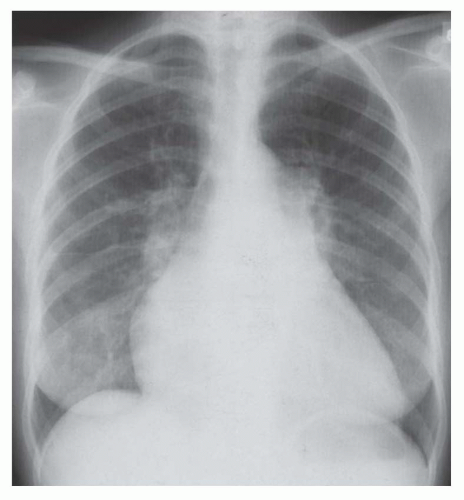

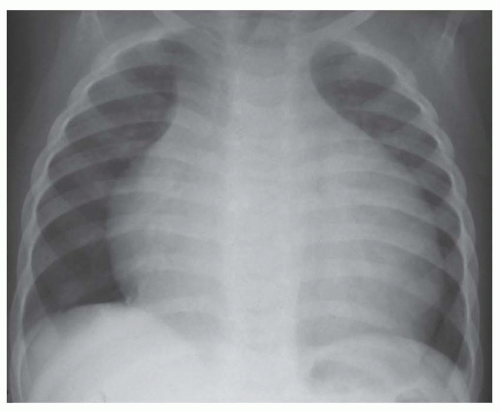

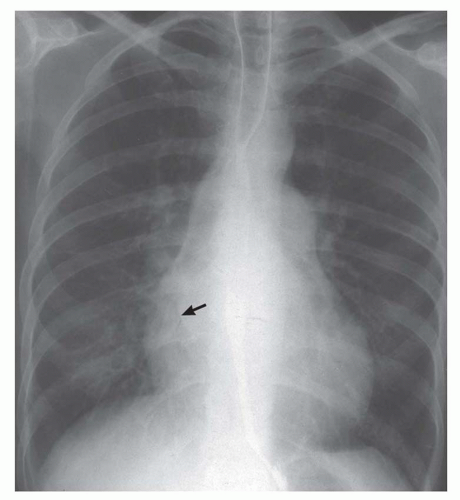

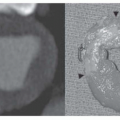

FIG. 30.5. Noncardiac pulmonary edema. Alveolar pulmonary edema with normal heart size in a child after drowning. |

secondary tumors of the heart and pericardium, mediastinal fibrosis, and complications of the Mustard procedure and other procedures used in congenital heart disease. Finally, pulmonary edema induced by reinflation of a collapsed lung or after thoracentesis must be considered.

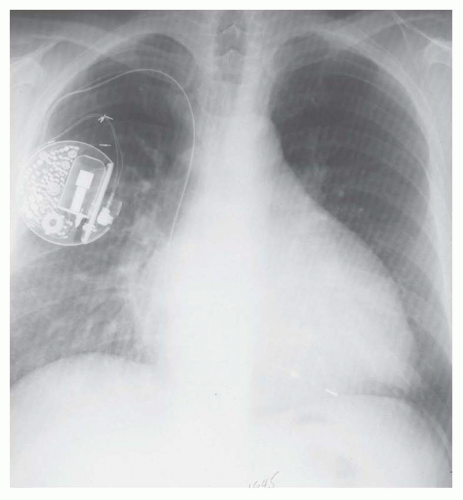

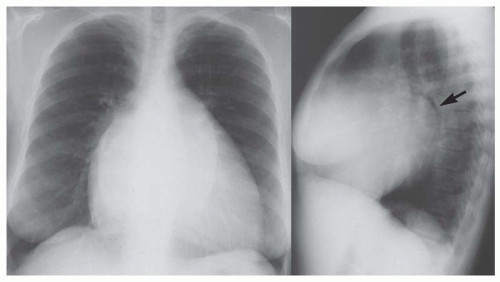

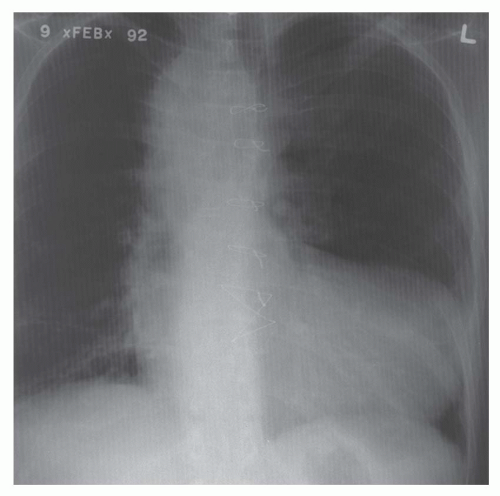

FIG. 30.6. Alveolar pulmonary edema with normal heart size in a patient with left atrial myxoma obstructing the mitral valve. |

TABLE 30.2 Signs of Pulmonary Ventricular Hypertension by Grade of Severity | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 30.4 Unilateral Pulmonary Edema | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 30.5 Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ventricles are enlarged. It is sometimes not possible to clearly determine the type of ventricular enlargement on the thoracic radiograph. The radiographic signs observed with enlargement of each of the cardiac chambers are given below.

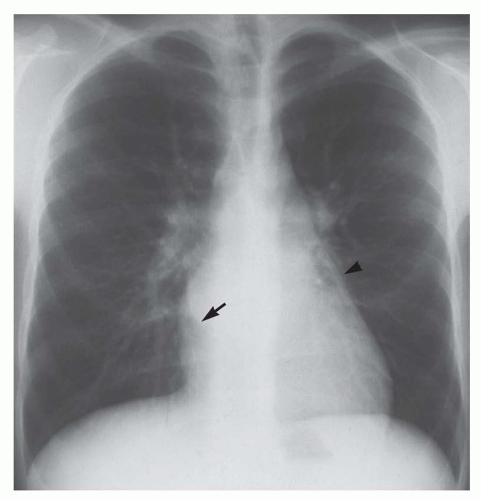

Right retrocardiac double density. Distance from the middle of the double density (lateral border of left atrium) to the middle of the left bronchus is less than 7 cm in greater than 90% of normal subjects and greater than 7 cm in 90% of patients with left atrial enlargement, proven by echocardiography (Figs. 30-8 and 30-9). In cases of severe left atrial enlargement, the right atrial border may extend further to the right than the right atrial border (Fig. 30-10).

Enlargement of the left atrial appendage. This is seen as a bulge along the left cardiac border just beneath the main pulmonary artery segment (see Figs. 30-8,30-9 and 30-10). Using the left bronchus as an orientation point, the bulge above it is the main pulmonary artery segment, while the bulge at the level of and/or just below the left bronchus is the left atrial appendage.

Splaying of the carina and/or elevation of the left bronchus (see Figs. 30-10 and 30-11)

Horizontal orientation of the distal portion of the left bronchus

Posterior displacement of the left upper lobe bronchus (see Fig. 30-11). On the lateral radiograph, the circular shadow of the right upper lobe and left bronchi is located within the tracheal air column. Left atrial enlargement causes displacement of the left bronchus posterior to this level and beyond the plane of the trachea.

Lateral bulging of the right heart border on the posteroanterior radiograph (see Fig. 30-11)

Elongation of the right heart border on the posteroanterior view. A rough rule is that a right atrial border exceeding 60% in length of the mediastinal cardiovascular shadow is a sign of substantial right atrial enlargement (Fig. 30-12).

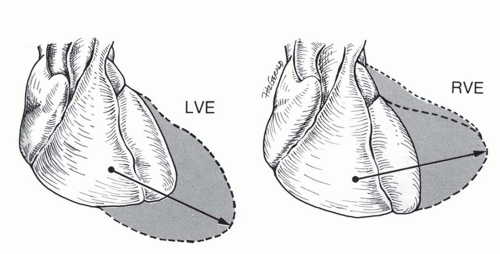

On the posteroanterior view, leftward and downward displacement of the cardiac apex. The vector of enlargement of the LV is leftward and downward compared with the vector of right ventricular enlargement, which is leftward only or perhaps leftward plus upward (Figs. 30-13 and 30-14).

On the lateral view, the posterior border of the heart is displaced posteriorly. The Hoffman-Rigler sign is measured 2.0 cm above the intersection of the diaphragm and the inferior vena cava. A positive measurement for LV enlargement is a posterior border of the heart extending more than 1.8 cm behind the inferior vena caval shadow at this level.

On the posteroanterior view, the left border of the heart is enlarged directly laterally or laterally and slightly superiorly (see Fig. 30-13). In some instances, this causes the apex to be displaced superiorly (“upward tipped apex”; Fig. 30-15); in the extreme form this causes a “boot shape” (Fig. 30-16).

On the lateral view, the retrosternal space is encroached upon by the enlarged right ventricle. Right ventricular enlargement is inferred by contact of the right heart border over greater than one third of the sternal length. A prominent convexity to the anterior border rather than the usual straight surface is an early sign of right ventricular enlargement.

Left atrial enlargement

Ascending aortic enlargement

Right atrial enlargement

Mitral valve (left atrium)

Aortic valve (ascending aorta)

Tricuspid valve (right atrium)

for diseases causing typical alterations in the chest x-ray. Of course, a specific cardiac lesion does not always cause typical features because of other associated abnormalities or because the lesion is very mild or has been present for insufficient time to alter the cardiac morphology to a degree discernible on the thoracic radiograph.

disease, then this signpost points to aortic regurgitation (see Fig. 30-14). If the right atrium is enlarged, then this signpost points to tricuspid regurgitation (see Fig. 30-11). Acquired pulmonic regurgitation is rare, except as a consequence of operation for right ventricular outflow obstruction, and is not considered in this schema. If no signposts are present, then the favored diagnostic considerations are congestive (dilated) cardiomyopathy or pericardial effusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree