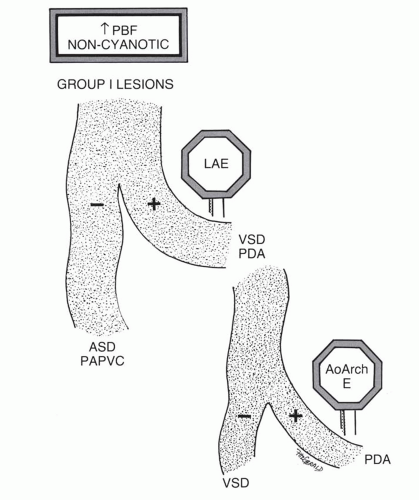

TABLE 31.1 Classification of Shunt Lesions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 31.2 Group V Lesions | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

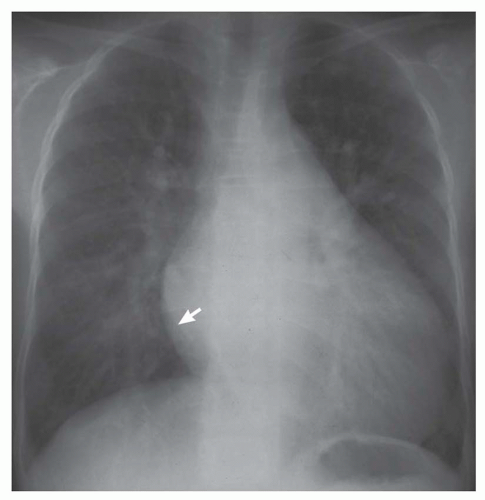

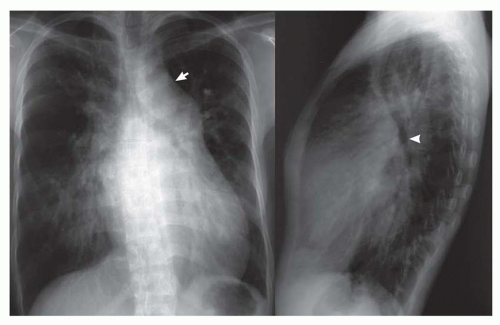

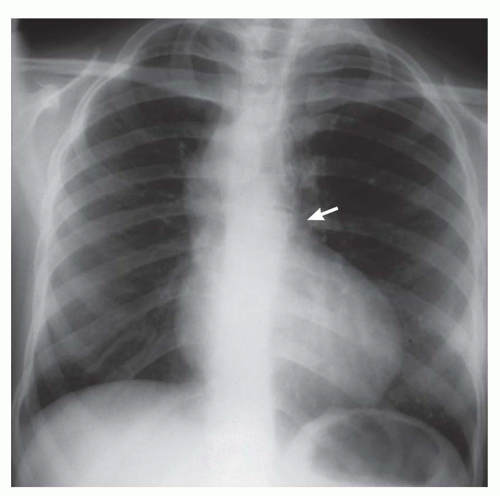

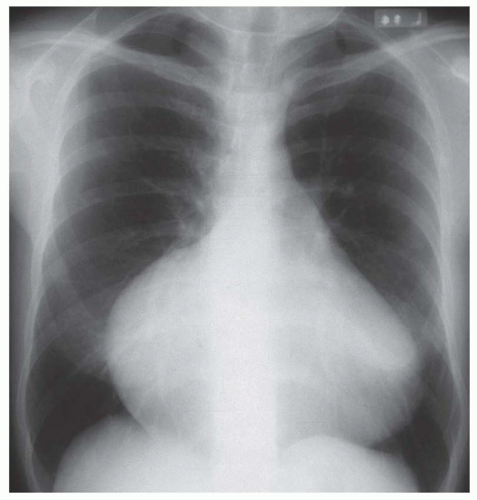

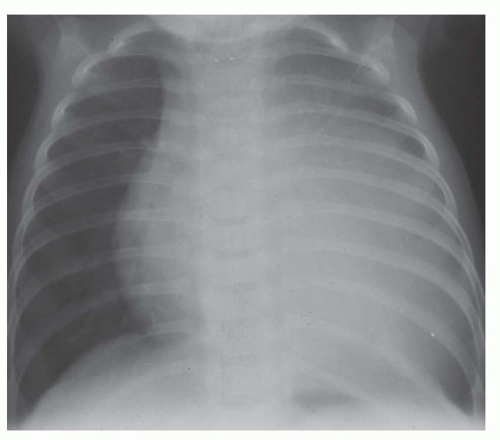

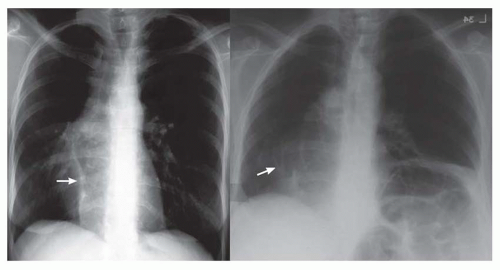

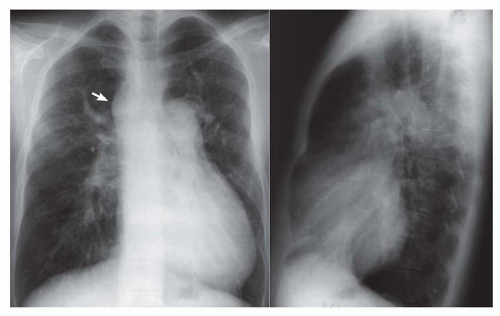

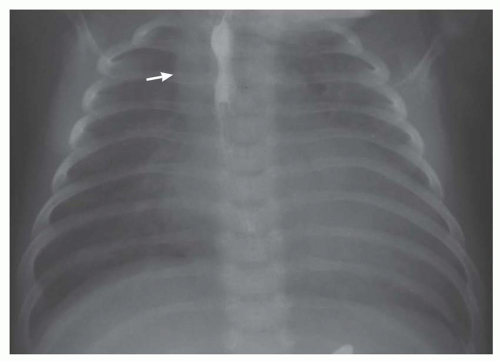

FIG. 31-4. Truncus arteriosus, type I. Note pulmonary arterial overcirculation in the presence of cyanosis and cardiomegaly. There is an enlarged aorta with right arch (arrow). |

When cardiomegaly exists out of proportion to the pulmonary arterial vascularity, then one must consider a number of possibilities. One of the possibilities is that the left-to-right shunt is diminishing in size because of a decrease in the size of the ventricular septal defect (VSD). Another consideration is the coexistence of additional cardiac lesions, such as primary myocardial disease or coarctation of the aorta.

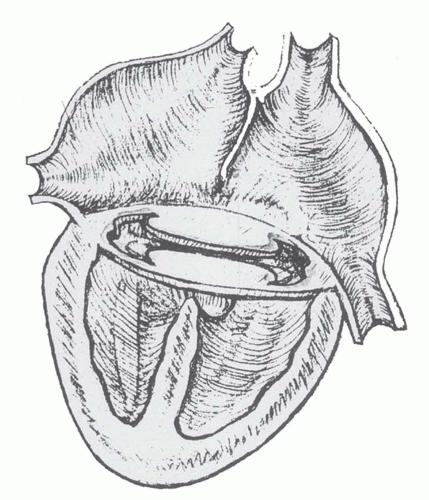

involves a nonrestrictive intracardiac shunt and a severe obstruction to pulmonary blood flow. The nonrestrictive intracardiac shunt permits equalization of the pressures between two chambers, and this prevents substantial enlargement of the right ventricle. Consequently, there is usually little or no cardiomegaly. An example of the importance of the size of the intracardiac defect is in patients with tricuspid atresia. The patient with tricuspid atresia with a large atrial septal defect demonstrates little or no cardiomegaly (Fig. 31-12). On the other hand, the patient with tricuspid atresia with a restrictive atrial septal defect experiences substantial right atrial enlargement, which results in cardiomegaly. Consequently, the former patient would be classified in group II, the latter patient in group III. Tricuspid atresia can be classified in group IV when there is an associated increase in pulmonary blood flow, which is caused by either a large left-to-right shunt at the ventricular septal level or the concurrence of transposition of the great vessels. Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) occurs in approximately 30% of patients with tricuspid atresia.

prompt the diagnostic consideration of a lesion causing tricuspid regurgitation.

total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (Fig. 31-18), tricuspid atresia, and single (“tingle”) ventricle. Doubleoutlet right ventricle and double-outlet left ventricle are also considered in this category, but these can be brought to mind when one thinks of TGA, since these lesions are essentially hybrids of TGA. The lesion that is frequently forgotten in this group is multiple pulmonary arterial venous malformations. The patient with multiple pulmonary arterial venous malformations is frequently mildly or even moderately cyanotic, and because of the several malformations within the lung, there is the appearance of increased pulmonary arterial vascularity.

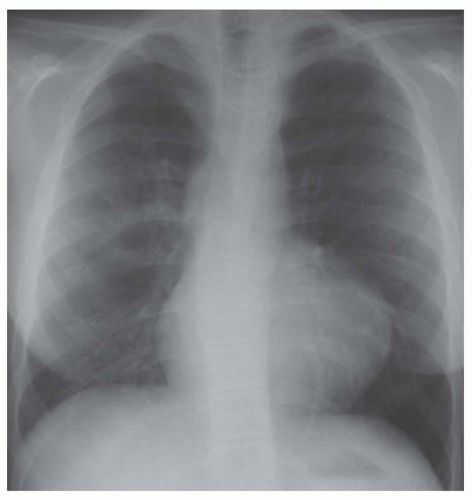

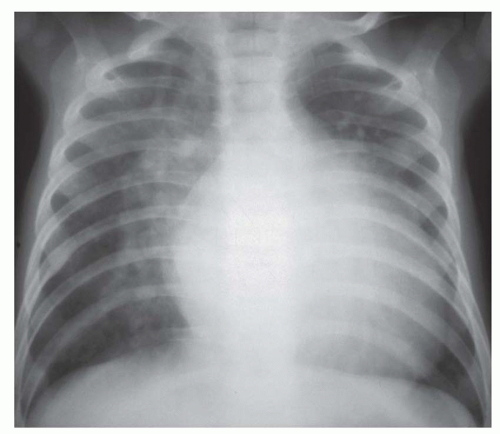

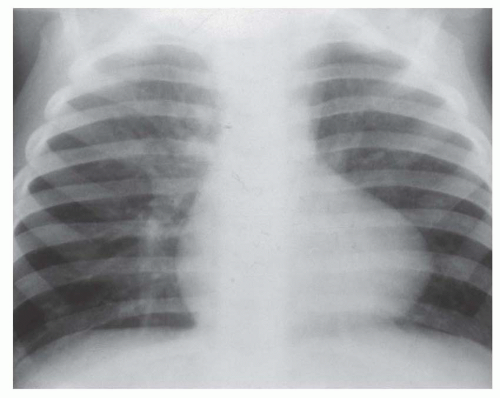

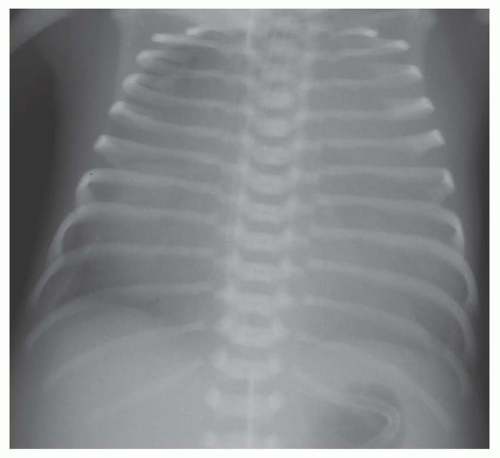

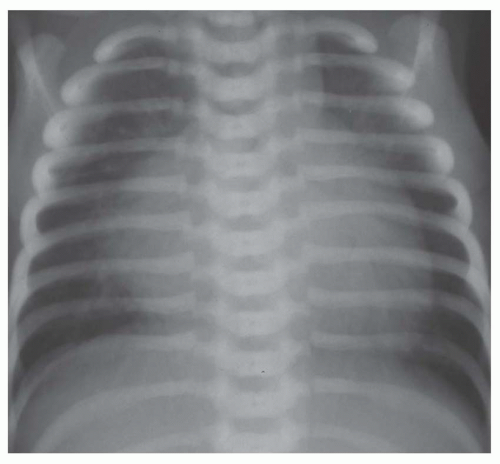

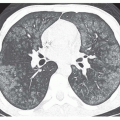

FIG. 31-16. Transposition of the great arteries. Pulmonary arterial overcirculation and an ovoid heart with a narrow base (vascular pedicle) of the heart are characteristic features. |

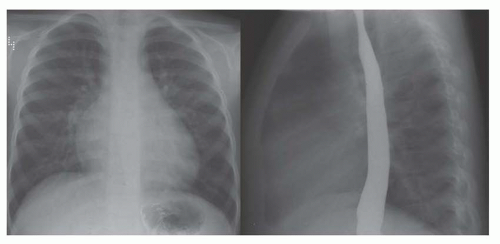

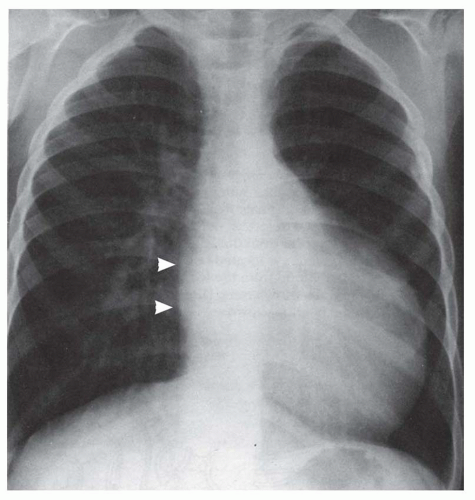

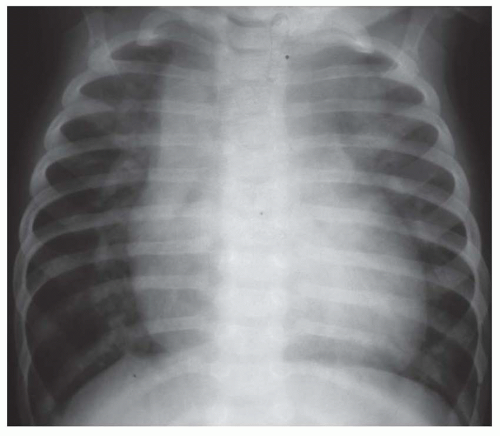

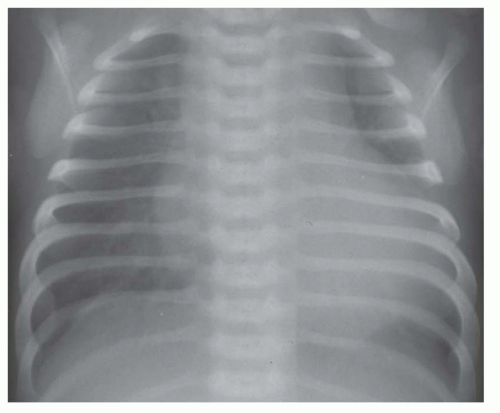

FIG. 31-17. Truncus arteriosus. Pulmonary arterial overcirculation and right aortic arch (arrow) are characteristics of truncus arteriosus. |

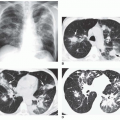

usually consist of dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia. The salient radiographic findings are indistinctness of the pulmonary vascularity, especially in the perihilar area, or interstitial pulmonary edema (see Figs. 31-19 and 31-21). Another observation that places a lesion into this group is disproportionately prominent cardiomegaly in comparison to the prominence of pulmonary vascularity (see Figs. 31-19 and 31-20).

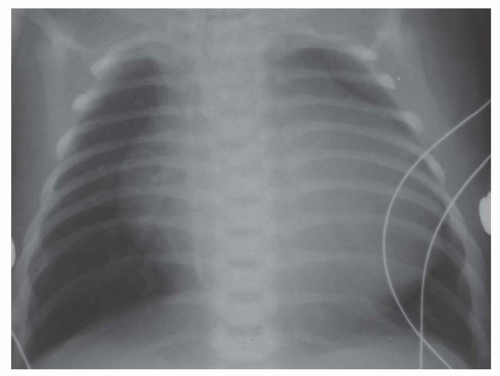

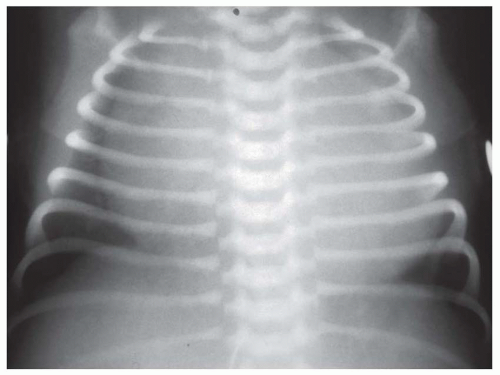

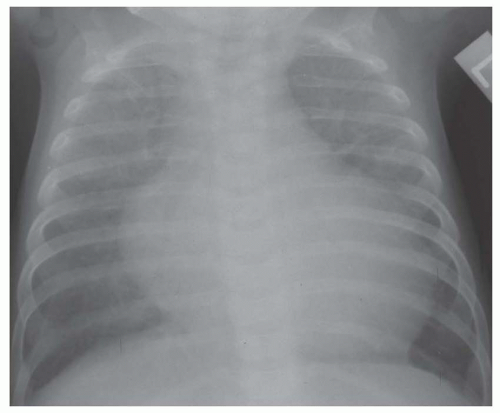

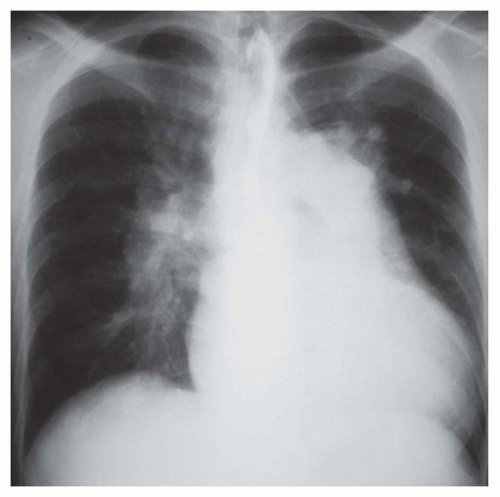

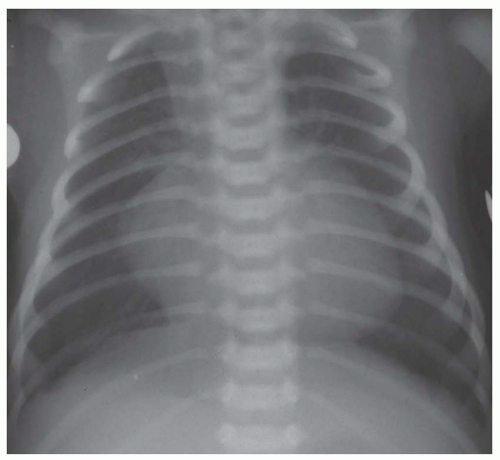

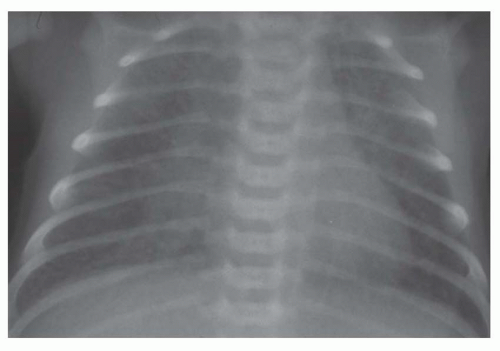

FIG. 31-21. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection, type III. Radiograph shows pulmonary edema and normal heart size. |

vena cava or in the lower septum and bordering on the ostium of the inferior vena cava. A rare type of defect occurs at a site normally occupied by the coronary site and coexists with absence of the wall separating the coronary sinus from the left atrium so that the associated left superior vena cava enters into the left atrium. The coexistence of large primum and secundum defects constitutes a common atrium.

TABLE 31.3 Salient Radiographic Features of Atrial Septal Defect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 31.4 Salient Radiographic Features of Atrial Septal Defect with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 31.5 Salient Radiographic Features of Partial Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Coarctation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

even in patients with substantial mitral regurgitation (Table 31-7; Figs. 31-27 and 31-28).

TABLE 31.6 Salient Radiographic Features of Scimitar Syndrome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

by malposition of the outlet septum, resulting in a small right ventricular outflow region and an aorta overriding the septal defect (tetralogy of Fallot). VSDs are not uncommonly multiple. Multiple defects in the trabecular septum may produce a “Swiss cheese septum.”

TABLE 31.7 Salient Radiographic Features of Atrioventricular Septal Defect | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree