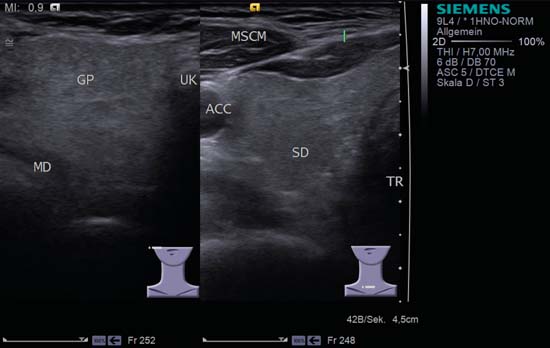

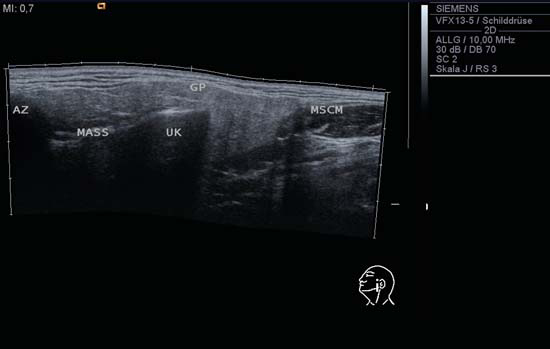

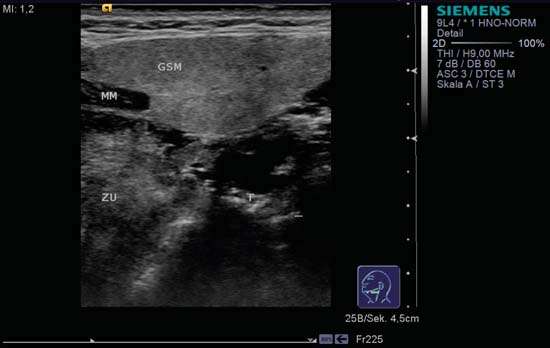

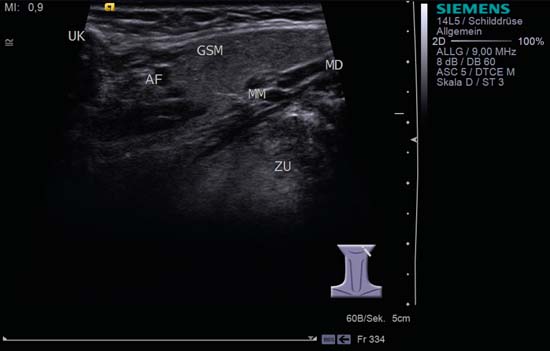

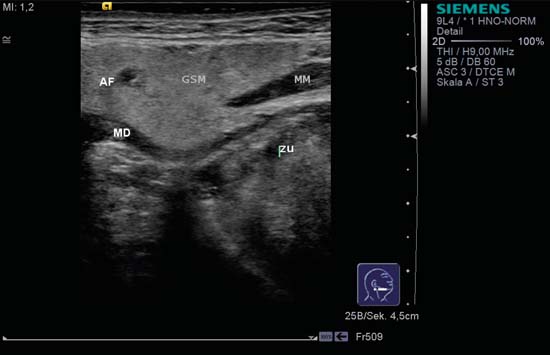

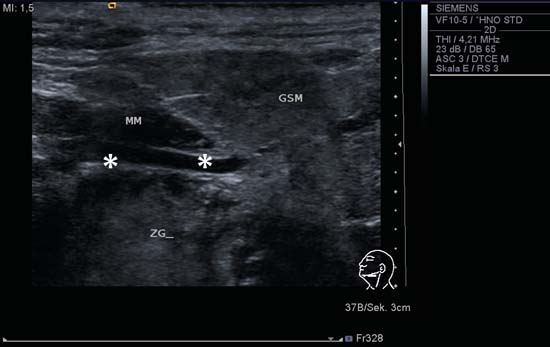

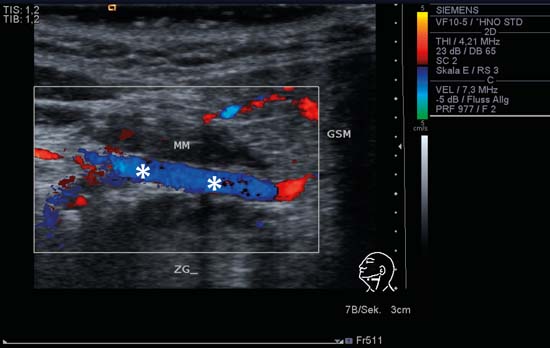

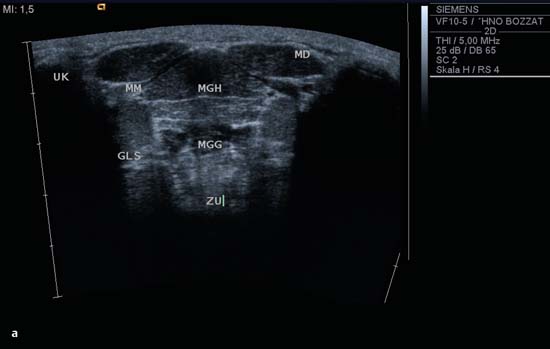

9 Salivary Glands Thanks to their superficial location, the three major salivary glands— the parotid, the submandibular, and the sublingual glands—are easily accessible to ultrasound examination. As a basic rule, the glands addressed in this chapter are seen as solid, homogeneous, echogenic structures with clearly defined margins and similar to the thyroid gland in appearance (Fig. 9.1). In the transverse plane, the parotid gland is a smoothly contoured, homogeneous, echogenic organ. It can be clearly distinguished from the subcutaneous fatty tissues. The anterior superficial lobe of the gland lies on the masseter muscle. The anterior end of the muscle can be differentiated from the hypoechoic buccal fat pad by getting the patient to contract and relax the muscles of mastication. Bordered anteriorly by the ascending ramus of the mandible and posteriorly by the mastoid and the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the main lobe of the gland lies in the retromandibular fossa. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the internal carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein can be identified lying mediocaudally to the lower pole of the parotid (Figs. 9.2, 9.3; Pearls and Pitfalls The hyperechoic signals from the styloid process may be mistaken for a salivary stone. With the high-resolution transducers currently available (7.5–18 MHz), it is also possible to demonstrate part of the parotid duct (Stensen duct) with ultrasound. However, it is generally not possible to see the duct clearly in the course of routine examinations if it is not obstructed. Pearls and Pitfalls The facial nerve itself and lymph nodes within the gland that are not enlarged are not visible on an ultrasound scan. In the longitudinal view, the submandibular gland has a pinecone-shaped appearance in the submandibular trigone, reaching cranially to the mandible and the mylohyoid muscle; it lies in close proximity to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, as well as to the tongue and tonsillar bed (Figs. 9.4, 9.5, 9.6; The submandibular gland arches over the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle and often extends as far as the sublingual gland in the ventromedial direction as an “uncinate process.” Pearls and Pitfalls An echogenic structure with distal acoustic shadowing can occasionally be seen projecting into the hilum of the submandibular gland. This could be either part of the hyoid bone or a salivary stone and these must be differentiated. The hyoid bone can be seen to move on swallowing, which helps to distinguish between the two. The ultrasound appearance of the submandibular gland is echogenic with a uniform texture, similar to the parenchymal echo pattern of the parotid gland (Fig. 9.7). Using a high-resolution ultrasound probe, segments of the submandibular (Wharton) duct can sometimes be seen even when it is not obstructed. Toward the mandible, where it runs close to the surface, the facial vein can be seen where it joins the internal jugular vein and can be compressed with the probe. The facial artery and vein, which can be demonstrated clearly on ultrasound, cross over the posterior part of the gland. The facial artery, originating from the external carotid artery, reaches the posterior margin of the gland or runs through the parenchyma in the shape of a walking stick (Fig. 9.8; It can sometimes be difficult to demonstrate the sublingual gland. The gland lies typically beneath the mucosa of the floor of the mouth, close to the frenulum, with the tip of the tongue lying above it. The posterior aspect of this gland, the smallest of the three major salivary glands, often touches the submandibular gland. The anterior and medial borders are formed by the geniohyoid and genioglossus muscles, with the mandible lying caudolaterally (Fig. 9.9a; Gaps in the musculature of the floor of the mouth may lead to a prolapse of the sublingual gland outwards (Fig. 9.9b and Fig. 9.1 Split screen of the thyroid (SD) and parotid gland (GP) on the left. Both solid glands show a similar homogeneous hyperechoic pattern of internal echoes. ACC, common carotid artery; MD, digastric muscle; MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle; TR, trachea; UK, mandible. Fig. 9.2 Panoramic view of the parotid bed (GP), left, transverse. The anterior lobes of the parotid gland lie on the masseter muscle (MASS); the anterior border with the oral cavity (CO) can be identified medially as an echogenic margin. More posteriorly it is bordered by the ascending ramus of the mandible (UK) and further posteriorly by the mastoid and sternocleidomastoid muscle (MSCM). The deep lobe of the gland lies in the retromandibular fossa. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle (MD) and retromandibular vein (VR) are situated deep in the gland parenchyma. BF, buccal fat pad; MAST, mastoid; SP, styloid process. Fig. 9.3 Panoramic view of the parotid bed (GP), left, longitudinal. The zygomatic arch (AZ) forms the cranial border; the sternocleidomastoid muscle (MSCM) flanks the inferior lateral pole caudally. The gland lies medially to the mandible (UK) and the masseter muscle (MASS). Fig. 9.4 Left transverse view of the submandibular region, showing the left submandibular gland (GSM) in longitudinal section. The anterior extension of the mylohyoid muscle (MM) divides the body of the gland and the uncinate process. The tongue (ZU) and tonsil (T) are immediately adjacent. Fig. 9.5 Cross-section of the left submandibular gland (GSM). The probe, however, is held sagittally in the craniocaudal direction. The mylohyoid muscle (MM) and digastric muscle (MD) can be seen clearly. The complete acoustic shadowing of the mandible (UK) forms the cranial/left border of the image. Lying almost immediately adjacent are the tongue (ZU) and tonsillar bed. The muscle fibers of the platysma can be distinguished as a hypoechoic layer, which forms the superficial border. AF, facial artery. Fig. 9.6 Longitudinal section of the right submandibular gland (GSM). The facial artery (AF) penetrates the posterior part of the gland, while the mylohyoid muscle (MM) tapers offanteriorly in the hilum of the gland. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle (MD) borders the gland at the caudal pole. The immediate vicinity of the oral cavity is clear from the position of the tongue (ZU). Fig. 9.7 Submandibular region, left, transverse. The parenchymal structure of the submandibular gland (GSM) is unremarkable but shows an anechoic band (asterisk), outlined by an echogenic contour in the hilar region between the mylohyoid muscle (MM) and the tongue (ZG). This was initially suspected to be a dilated submandibular duct. Fig. 9.8 Submandibular region (GSM), left, transverse. After activating the color duplex mode, an artery (asterisk) with clear flow signals can be seen running parallel to the duct. It is very similar in appearance to the duct in the B-mode image. MM, mylohyoid muscle; ZG, tongue. Fig. 9.9a Midline transverse view of the floor of the mouth/mid-tongue. The paired sublingual glands (GLS) lie medial to the inner side of the mandible (UK). The muscles of the floor of the mouth and of the tongue constitute the surrounding structures. MD, digastric muscle; MGG, genioglossus muscle; MGH, geniohyoid muscle; MM, mylohyoid muscle; ZU, tongue. Fig 9.9b Floor of the mouth, paramedian, right, transverse. The right sublingual gland (GSL) is luxated outward through the mylohyoid muscle (MM) by contraction of the tongue. Diagnosis: Muscular dehiscence of the mylohyoid muscle. When the relevant clinical picture calls for further investigation, ultrasonography shows acute sialadenitis as a diffuse enlargement of the entire diseased gland. The organ can usually be distinguished clearly from adjacent structures. The parenchymal pattern appears enlarged, more loosely structured, inhomogeneous, and more hypoechoic than usual (Figs. 9.10, 9.11, 9.12; This finding can be attributed to the infection-/inflammation-related increased volume of fluid within the gland. Circumscribed hypoechoic space-occupying lesions can occasionally be seen, providing evidence of an associated inflammatory reaction in the intraglandular lymph nodes. The submandibular gland is the exception here, as no lymph nodes have been described within it. Ultrasonography alone cannot establish whether the parenchymal changes are of bacterial or viral origin. The most common viral agents are paramyxo-, cytomegalo-, coxsackie-, ECHO-. influenza, parainfluenza and human immunodeficiency viruses. For suppurative sialadenitis Staphhylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and pyogenes and Haemophilius influenzae are found in many cases. A pus-filled duct can often be demonstrated in suppurative sialadenitis, indicating an obstructive etiology, but it may also occur without any obstruction in patients who are dehydrated (marantic parotitis). Areas of liquefaction appear hypoechoic to anechoic, enclosed by an echogenic wall, with clear distal acoustic enhancement absent of perfusion on color-coded duplex sonography (CCDS) (Figs. 9.13, 9.14; Coarse central echoes in the focus of this liquefaction may correspond to necrotic tissue. The palpatoric impression by the ultrasound transducer further undermine a suspected abscess. It is difficult to attribute it to any specific cause (stenosis, calculus) at this stage and it should be investigated further with repeat ultrasound scanning once the acute phase has settled. The ultrasound appearance of the gland depends significantly on the duration and extent of the infection/inflammation in the parenchyma. Overall, the echotexture is clearly coarser; the internal echoes appear inhomogeneous, probably as a result of parenchymal fibrosis causing scarring. With advancing functional impairment, the parenchyma becomes more echogenic and shrinks in size. Small cystic areas, consistent with circumscribed duct ectasia, may also appear. These changes are regularly observed following radiation therapy (Figs. 9.15, 9.16) and obstructive sialopathies that have assumed a chronic course (Fig. 9.17, 9.18, 9.19). The various pathogenic causes of chronic sialadenitis cannot be differentiated with certainty with ultrasonography; circumscribed, hypoechoic, clearly defined areas of gland parenchyma may also be histologically consistent with inflammatory foci. Chronic recurrent juvenile parotitis is a rare condition in childhood and adolescence; and frequently leads to changes in both parotid glands that are visible on ultrasonography (Fig. 9.20; A particular type of chronic inflammation in the submandibular gland—sclerosing sialadenitis (Küttner tumor)—is often found at the edge of the gland, as a focal hypoechoic, sometimes inhomogeneous lesion within the glandular tissue (Figs. 9.21, 9.22). Ultrasonography of the diseased salivary glands in primary and secondary Sjögren syndrome shows the affected glands with an inhomogeneous hypoechoic texture. There are numerous circumscribed hypoechoic lesions that could be either cystic enlargements of the ducts or enlarged intraglandular lymph nodes. The overall appearance is described as “cloudlike” or “leopard skin” (Figs. 9.23, 9.24, 9.25; One particular feature is the presence of intraglandular and cervical lymph nodes, which may indicate the local development of a MALT lymphoma (Fig. 9.26; Pearls and Pitfalls Sjögren syndrome, chronic recurrent juvenile parotitis and sarcoidosis present similar images on ultrasound. Diagnosis can be confirmed by clinical presentation and age of the patient. Epithelioid cell sialadenitis (Heerfordt syndrome) is an acute presentation of sarcoidosis characterized by an enlarged gland with an echogenic internal structure, studded with multiple enlarged lymph nodes—corresponding to the hypoechoic areas seen on ultrasonography (Fig. 9.27). Strong irregular perfusion is found on CCDS (Fig. 9.28). Whenever the condition is accompanied by enlarged cervical lymph nodes, these also show strong hilar perfusion (see also Chapter 6, Figs 6.3 and 6.7 ). Ultrasonography usually shows multiple hypoechoic lesions lying within an unremarkable gland parenchyma. These lesions do not exhibit a marked distal acoustic enhancement. As a rule, the central hyperechoic structure (“hilar sign”) can be identified clearly in inflammatory lymph nodes. Furthermore, a hilar/central perfusion pattern is indicative of an inflammatory origin (Fig. 9.29). In the salivary glands, too, ultrasonography does not provide any definitive evidence of benign or malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis of lymph node enlargement. With respect to ultrasound examination, it is also not possible to differentiate with certainty between reactive lymphadenitis, lymphoma, and metastatic growth within the gland, but there are several morphological features (Fig. 9.30, 9.31, 9.32, 9.33, 9.34; On the other hand, ultrasonography makes it very easy to assess whether a lesion is situated within the gland tissue or lying caudally in an “extracapsular” position (Fig. 9.35). In the differentiation between benign and malignant lesions the same criteria apply as in Chapter 6 (p. 58). As a rule, congenital and acquired salivary gland cysts are filled with more or less serous secretions. On this basis, they meet the typical ultrasound criteria for cystic structures: hypoechoic space-occupying lesions, with clearly defined margins and typical distal enhancement (Figs. 9.36, 9.37, 9.38; Lymphoepithelial cysts, associated with HIV infection, should also be considered if there is a relevant medical history and ultrasonography shows cystic space-occupying lesions in both parotid glands (Figs. 9.39, 9.40). The classic sonographic criterion for a stone (calculus) is a dense echo with clear distal acoustic shadowing (direct signs of a stone) (Figs. 9.41, 9.42). While distal acoustic shadowing can routinely be demonstrated, the dense echo is sometimes not absolutely clear or cannot be seen at all. A further indirect sign of a salivary stone is the buildup of secretions in the salivary duct (in the absence of a demonstrable calculus). Because of the great difference in impedance, stones in the major salivary glands can certainly be seen on ultrasonography once they have reached ~2 mm in size. The view of small stones lying very anteriorly in the floor of the mouth, which is restricted by the shadow of the mandible, can be improved by tilting the probe (Figs. 9.43, 9.44; In considering treatment options, determination of the precise location of the salivary stone (intra- or extraglandular, intraductal) is extremely important. Ultrasound-guided palpation of the stone may be helpful in pinpointing its precise position (Fig. 9.45). Pearls and Pitfalls While about 90% of the stones in the parotid gland are found in the middle and distal segments of the duct, two-thirds of those in the submandibular gland lie in the hilar region of the gland. Differentiation of a salivary stone from an obstructive stenosing sialodochitis can be difficult in some cases when, as mentioned previously, there are only indirect signs of obstruction (Figs. 9.46, 9.47; Further investigation with sialendoscopy

Anatomy

Parotid Gland

Video 9.1). The retromandibular vein lying in the parenchyma of the gland can be seen particularly well in the longitudinal view (

Video 9.1). The retromandibular vein lying in the parenchyma of the gland can be seen particularly well in the longitudinal view ( Video 9.2). In the transverse view, the styloid process often projects beneath the vein as a hyperechogenic reflection in the parenchyma of the gland.

Video 9.2). In the transverse view, the styloid process often projects beneath the vein as a hyperechogenic reflection in the parenchyma of the gland.

Submandibular Gland

Video 9.3).

Video 9.3).

Video 9.4).

Video 9.4).

Sublingual Gland

Video 9.5a).

Video 9.5a).

Video 9.5b).

Video 9.5b).

Inflammatory Changes

Acute Sialadenitis

Video 9.6).

Video 9.6).

Salivary Gland Abscess

Video 9.7).

Video 9.7).

Chronic Sialadenitis

Video 9.8). In the acute stage, the changes are similar to those of acute obstructive sialadenitis. Chronic recurrent sialadenitis in adults may look similar to the juvenile form but it is frequently accompanied by visualization of dilated segments of the parotid duct.

Video 9.8). In the acute stage, the changes are similar to those of acute obstructive sialadenitis. Chronic recurrent sialadenitis in adults may look similar to the juvenile form but it is frequently accompanied by visualization of dilated segments of the parotid duct.

Video 9.9). With advanced disease, all salivary glands are affected by this autoimmune sialopathy and show similar ultrasound changes in the parenchyma.

Video 9.9). With advanced disease, all salivary glands are affected by this autoimmune sialopathy and show similar ultrasound changes in the parenchyma.

Video 9.10).

Video 9.10).

Enlarged Lymph Nodes

Videos 9.11, 9.12, 9.13).

Videos 9.11, 9.12, 9.13).

Salivary Gland Cysts

Video 9.14). The more viscous the cyst contents, the more echogenic is the ultrasound appearance. Intrinsic perfusion is not found in cysts, but can be demonstrated in solid tumors with cystic components. A special form of salivary gland cyst, the ranula, is described in Chapter 8 (p. 99).

Video 9.14). The more viscous the cyst contents, the more echogenic is the ultrasound appearance. Intrinsic perfusion is not found in cysts, but can be demonstrated in solid tumors with cystic components. A special form of salivary gland cyst, the ranula, is described in Chapter 8 (p. 99).

Sialolithiasis and Obstructive Disease

Video 9.15). Differential diagnostic thought must be given to phlebolith, atherosclerosis, calcified lymph node, scar formation, malignant tumor, foreign body, arteriovenous malformation and hemangioma.

Video 9.15). Differential diagnostic thought must be given to phlebolith, atherosclerosis, calcified lymph node, scar formation, malignant tumor, foreign body, arteriovenous malformation and hemangioma.

Video 9.16).

Video 9.16).

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree