Chapter 32 Sarcomas

Soft tissue sarcomas

Pathology

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification is the most commonly used, but this is extremely complex and a simplified version listing malignant tumours by their tissue of origin is presented in Table 32.1. From the point of view of management and prognosis, the histological subtype of management is generally less important than the histological grade and the size of the tumour. Grading may depend in part on the tumour subtype, but more often is assessed by scoring the degree of necrosis and mitotic index. The system described by Trojani is in regular use both in the UK and internationally. Low-grade tumours have a recognizable pattern of differentiation, relatively few mitoses, and no necrosis. High-grade tumours include all examples of certain subtypes (e.g. alveolar soft part), tumours with little or no apparent differentiation, and those with necrosis and a high mitotic rate. The tumour size is also important, and those over 5 cm are much more likely to recur locally or give rise to distant metastases.

Table 32.1 Simplified version of the WHO classification of sarcomas

Diagnosis and staging

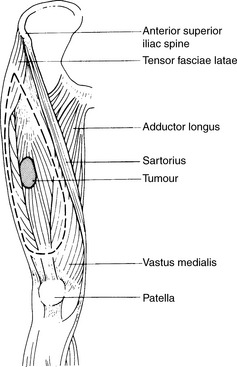

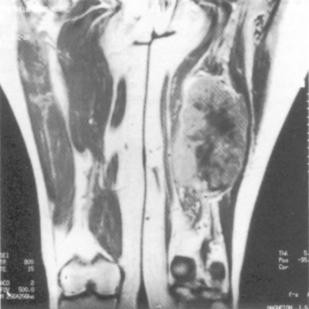

A full blood count, liver function tests, chest radiograph, plain radiographs of the tumour-bearing region (Figure 32.1) and liver ultrasound are the initial investigations. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figures evolve 32.2–32.4![]() ) scanning are important in defining the local extent and operability of the tumour. MRI is the imaging modality of choice for limb sarcomas since it provides good contrast between the tumour and adjoining normal tissues with particular regard to the tumour’s relationship with the neurovascular bundle. It also provides better multiplanar versatility in planning surgery and radiotherapy. CT can be helpful in exclusion of cortical erosion of bone. CT and MRI are also useful in confirming any subsequent local recurrence, but are not currently used for routine follow up. CT of the thorax is advisable if chest radiography is normal and radical therapy is contemplated, since it may demonstrate small-volume lung metastases (Figure evolve 32.5

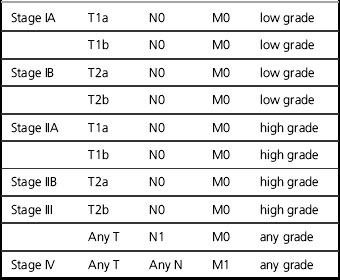

) scanning are important in defining the local extent and operability of the tumour. MRI is the imaging modality of choice for limb sarcomas since it provides good contrast between the tumour and adjoining normal tissues with particular regard to the tumour’s relationship with the neurovascular bundle. It also provides better multiplanar versatility in planning surgery and radiotherapy. CT can be helpful in exclusion of cortical erosion of bone. CT and MRI are also useful in confirming any subsequent local recurrence, but are not currently used for routine follow up. CT of the thorax is advisable if chest radiography is normal and radical therapy is contemplated, since it may demonstrate small-volume lung metastases (Figure evolve 32.5![]() ). The staging system commonly adopted includes grade, size, and presence/absence of metastases (Tables 32.2 & 32.3).

). The staging system commonly adopted includes grade, size, and presence/absence of metastases (Tables 32.2 & 32.3).

Figure 32.1 MRI scan showing soft tissue sarcoma with central necrosis in the hamstring compartment of the thigh.

(Courtesy of Dr L Turnbull, MRI Unit, Sheffield.)

Table 32.2 Stage grouping for soft sarcoma (UICC 2009) – taking into account histopathological grade

Table 32.3 Staging system for soft tissue sarcomas (UICC 2009)

| T1 | ≤ 5 cms |

| T1a | Superficial |

| T1b | Deep |

| T2 | >5 cms |

| T2a | Superficial |

| T2b | Deep |

| N0 | No lymph node spread |

| N1 | Involvement of regional lymph nodes |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Management

Local control while maximizing the probability of conserving limb function and long-term survival is of vital importance. For extremity limb sarcomas, 90% local control at 5 years should be the standard. The management of soft tissue sarcomas is controversial. In part, this reflects the limited number of randomized trials in this heterogeneous group of tumours. The relative rarity of non-extremity sarcomas makes the design of and recruitment to large randomized trials difficult. Few would dispute the primary role of radical surgery. If the surgical resection margins are clear, the 5-year local control for limb sarcomas is of the order of 90%. If the margins are involved, this falls to 60–80%. Involved margins are an independent risk factor for local recurrence. The extent of the resection will depend upon the site of the tumour. The more distal the tumour in the limb, the more difficult a complete excision becomes. Radical excision surgery of retroperitoneal sarcomas is also rarely feasible. The primary tumour should be resected with one anatomical plane clear of the tumour at all stages. The aim of the surgery is to achieve a wide local excision (margin ≥2 cm where possible) (Figure 32.6). The resection should include all the skin and subcutaneous tissue near to the tumour, any previous excision or biopsy scars and areas containing blood clot from previous biopsies. The tumour itself should never be actively contacted during resection. Metallic clips at the margins of the excision are helpful in planning postoperative irradiation.

Amputation for extremity sarcomas is only indicated in the following situations:

1. when serious radiation-induced morbidity would result from attempting radical radiotherapy

2. in some distal limb sarcomas, where a below knee amputation may be more functional than a lower limb with the combined local morbidity of surgery and radiotherapy

3. when there is recurrent disease not suitable for limited resection or adjuvant radiotherapy.

Adjuvant therapy

• limb-conserving or limited surgery (see below)

• gross residual tumour or inadequate excision margins

• tumours 5 cm or more in any dimension plus most tumours deep to the fascia

• virtually all tumours in the head and neck (because of the impossibility of adequate excision).

• after surgery for recurrent sarcoma if not previously irradiated.

Not all sites are suitable for radical radiotherapy. Pelvic, thoracic or abdominal sarcomas present particular difficulties because of the morbidity that would be caused by wide-field irradiation, dose-limiting critical structures (e.g. the spinal cord). Placement of spacers in the abdominal cavity may be used to displace small bowel out of the high dose radiation field (Figures evolve 32.7 and 32.8![]() ).

).