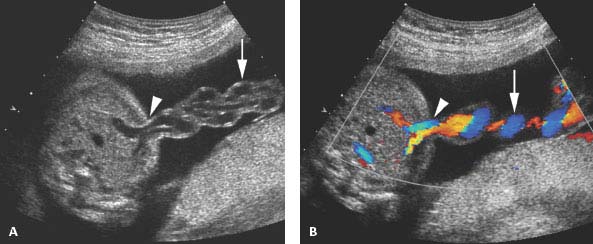

Figure 3.1.1

Figure 3.1.1

Umbilical cord insertion into placenta. The umbilical cord appears as a thin-walled curvilinear structure (arrow) extending from its insertion site into the placenta (arrowhead), in grayscale (A) and color Doppler images (B).

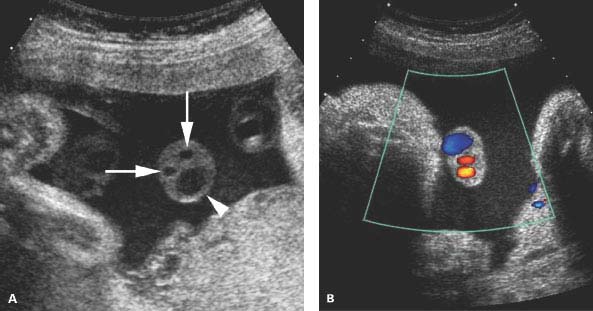

Figure 3.1.2

Figure 3.1.2

Umbilical cord insertion into the fetus. The umbilical cord (arrow) is seen inserting into the fetal anterior abdominal wall (arrowhead), in grayscale (A) and color Doppler images (B).

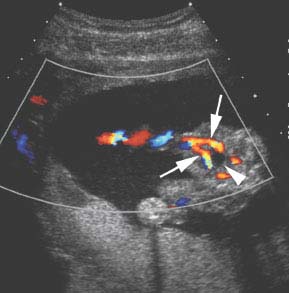

Figure 3.1.3

Vascular composition of the cord. A: Grayscale image of a cross-section of the umbilical cord reveals two arteries (arrows) and one vein (arrowhead). B: Color Doppler of a cross-section of the umbilical cord reveals two arteries (small red dots) and one vein (larger blue structure).

Figure 3.1.4

Figure 3.1.4

Doppler demonstration of two umbilical arteries in the fetal pelvis. Color Doppler image of the fetal pelvis reveals two umbilical arteries (arrows) coursing lateral to the fetal bladder (arrowhead).

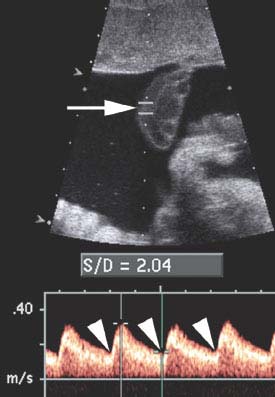

Figure 3.1.5

Umbilical arterial spectral Doppler. Spectral Doppler gate (arrow) is placed within the umbilical artery. On the resulting spectral waveform, there is a normal pulsatile pattern with forward blood flow throughout the cardiac cycle, including diastole (arrowheads). The systolic/diastolic ratio is 2.04, which is within normal limits.

3.2. Cervix in Pregnancy

Description and Clinical Features

The cervix is a cylinder of muscular tissue that forms the most caudal portion of the uterus. The cervix protects the intrauterine pregnancy from ascending infections and prevents the gestational sac from passing out of the uterus prematurely. It normally remains long and closed until term. When labor ensues, the cervix becomes shortened, effaced, and dilated, allowing the fetus to be delivered through the cervical canal.

Sonography

The cervix can be evaluated sonographically using a transabdominal, translabial, or transvaginal approach. The transvaginal approach provides the highest resolution view and the most consistent visualization of the cervix, but the transabdominal approach is generally adequate in the low-risk patient. If the cervix cannot be adequately visualized transabdominally, as may happen when the fetal presenting part obscures the cervix, translabial or transvaginal sonography may be necessary to assess the cervix.

With any of these approaches, the normal cervix appears as a fairly homogeneous structure between the vagina and the lower uterus, measuring at least 3 cm in length (Figure 3.2.1). The endocervical canal is generally visible as a thin line running the length of the cervix and may be hypo- or hyperechoic with respect to the rest of the cervix. Its appearance derives from the apposition of the circumferential walls of the canal, and cervical mucus within the canal. One or more Nabothian cysts may be seen within the cervix.

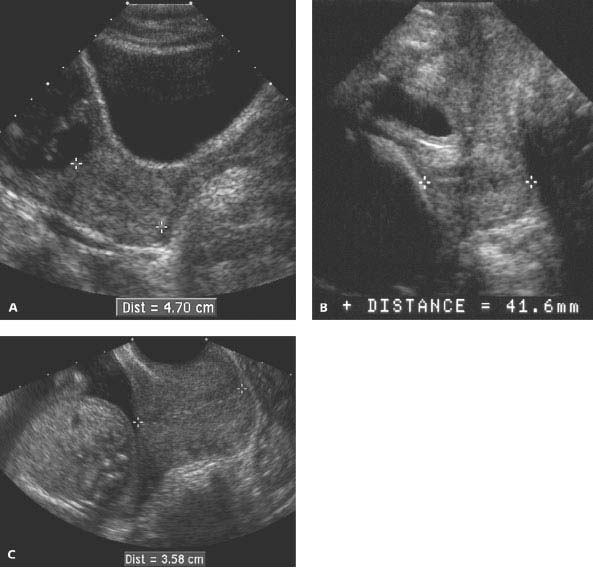

Figure 3.2.1

Normal cervix. The cervix is normal in configuration and length (calipers) on transabdominal (A), translabial (B), and transvaginal (C) sonograms, measuring at least 3 cm on each of these sagittal images.

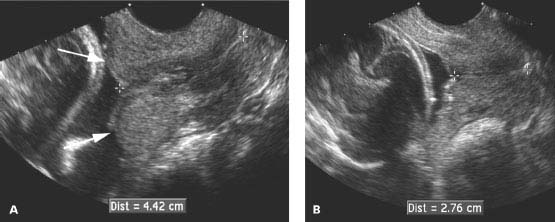

Figure 3.2.2

Pitfall in cervical length measurement: lower uterine segment contraction. A: Sagittal view of the lower uterus demonstrates a rounded bulge (arrows) in the lower uterine segment, contiguous with the cervix, representing a uterine contraction. The distance of 4.42 cm between the calipers represents the length of both the cervix and the contraction, and thus is greater than the length of the cervix itself. If the presence of a contraction is not recognized, the cervical length will be overestimated. B: After the contraction resolved a few minutes later, the cervical length (calipers) is measured at 2.76 cm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree