and Siddharth P. Jadhav2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch Pediatric Radiology, Galveston, TX, USA

(2)

The Edward B. Singleton Department of Pediatric Radiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract

This chapter deals with injuries of the shoulder and upper humerus, including the clavicle. Various types of fractures and other injuries are presented. MR is discussed where it significantly adds to evaluation of these injuries.

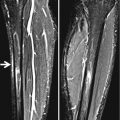

Normal Soft Tissues

There are no specific fat pads or soft tissues to evaluate around the shoulder or over the humerus. However, over the clavicle, the companion shadow is useful. This shadow represents the air-covered edge of the skin over the underlying soft tissues as they pass over the clavicle. Depending on positioning, this shadow is visible in most patients. However, it can become obliterated if there is swelling over the clavicle due to any inflammatory or traumatic cause of edema. This finding is readily evaluated and visualized when both shoulders are obtained on the same image (Fig. 5.1).

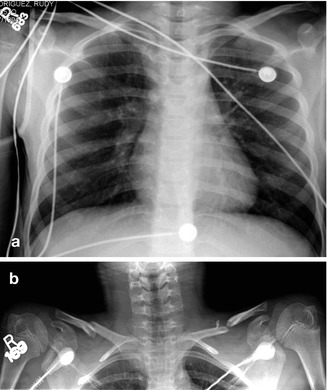

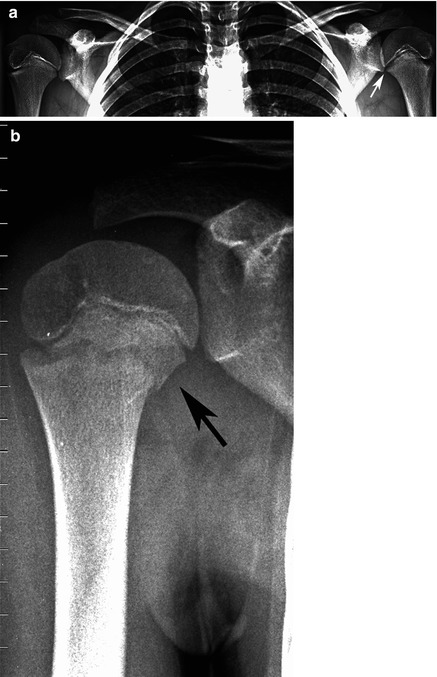

Fig. 5.1

Value of companion shadow. Note the companion shadow (arrowheads) over the left clavicle. On the right, there is no companion shadow because there is edema from an upward bending greenstick fracture (arrow)

Joint Fluid

Fluid in the shoulder joint, be it pus, serous effusion, or blood, causes lateral displacement of humeral head and widening of the joint space, but this generally occurs only in very young children and infants. In older children, the joint capsule is too tight to allow this to happen. Associated swelling and edema of the soft tissues around the shoulder may or may not be present.

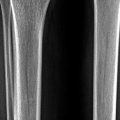

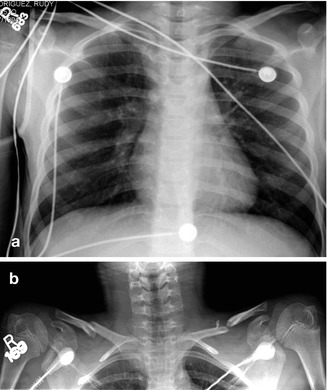

Clavicular Injuries

Overall, the clavicle is the most commonly injured bone of the shoulder in infants and young children. Injury usually results from falling on an outstretched extremity, falling directly on the shoulder, or from a direct blow to the clavicle. By far the most common location for a clavicular fracture is the midshaft, and while many such fractures are easy to identify, others are more elusive and can be hidden on one view (Fig. 5.2). In addition many clavicular fractures are not overt but rather greenstick or plastic bending fractures. Detecting these fractures is best accomplished by comparing one clavicle with the other, and any discrepancy should be treated with suspicion. In addition, one also should assess the soft tissues for a general increase in supraclavicular density resulting from edema and bleeding, and obliteration of the companion shadow of the clavicle (Fig. 5.3).

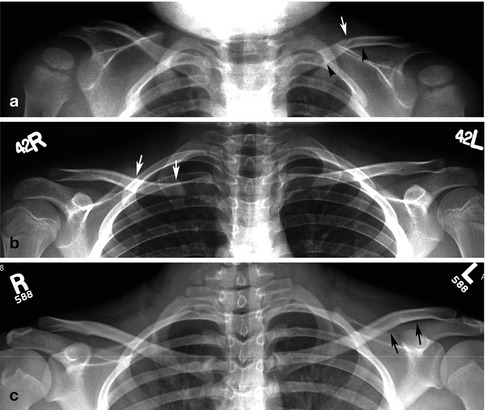

Fig. 5.2

Clavicle fracture, occult. (a) In this trauma patient, the clavicles appear normal. (b) A more dedicated view demonstrates bilateral displaced midshaft fractures. Fractures through the clavicle often are hidden on any given view

Fig. 5.3

Plastic bending–greenstick fractures: spectrum. (a) In this patient, there is an upward plastic bending fracture (black arrowheads) of the left clavicle. There also is a very subtle greenstick fracture visible over the superior surface (arrow) of the upwardly bent clavicle. (b) In this patient, there is a downwardly bent plastic bending fracture (arrows) through the medial half of the clavicle on the right. Compare with the normal clavicle on the left. (c) In this patient, a subtle upward plastic bending fracture (arrows) is seen through the lateral third of the left clavicle. Compare with the normal appearance of the right clavicle

Acromioclavicular separations are not particularly common in infants and young children but are more common in the older child and adolescent. In such cases, one should first look for soft tissue prominence (bump) over the acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 5.4a) and then for separation of the joint itself. In addition, although the acromioclavicular joint is widened, one often also can see widening between the clavicle and the coracoid process of the scapula. Indeed, separation at this site caused by ligamentous sprain often is easier to detect than is acromioclavicular separation (Fig. 5.4b). In some cases, an associated coracoid process avulsion fracture can occur. In the infant and young child, rather than pure acromioclavicular separation, a fracture through the lateral end of the clavicle usually is sustained (Fig. 5.4c–e).

Fig. 5.4

Distal clavicular injuries. (a) Acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular separation. Note increased space between the distal clavicle and acromion (white arrow) and increased distance between the coracoid process and clavicle (black arrow). (b) Normal side for comparison. (c) Clavicle fracture and coracoclavicular ligament tear. Note the overt fracture through the distal clavicle (white arrow) and the increased coracoclavicular distance (black arrows). (d) Typical distal clavicular fracture. Note the typical buckle fracture (arrow) through the distal clavicle. This is the most common injury seen in this area in children. (e) Sleeve fracture of clavicle. Note the avulsed sleeve fracture (arrow) of the distal clavicle

Medial clavicular injuries usually consist of anterior or posterior dislocations. In actual fact, these injuries are not dislocations but displaced Salter–Harris I or II fractures [1, 2]. The medial clavicular epiphysis is one of the last to fuse and it remains a weak point throughout adolescence and early adulthood. Because of this, any stresses applied to this area can result in a fracture dislocation. With anterior displacement, a clinically visible and palpable bulge is present over the involved sternoclavicular joint. With posterior displacement, such a clinical bulge is not present, but it is a more serious problem in terms of compression of neck vessels or the trachea [1, 2].

On frontal view, dislocation of the medial end of the clavicle, either anterior or posterior, should be suspected if the medial end of the involved clavicle is lower or higher than the medial end of the normal clavicle (Fig. 5.5). However, in some cases of anterior or posterior dislocation, the clavicles align normally on the AP view. In such cases, if there is any clinical suspicion of dislocation, one should proceed to CT with IV contrast for it will clearly define dislocation along with any associated vascular or visceral injury (Fig. 5.6).

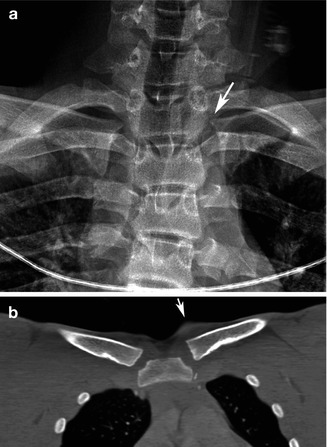

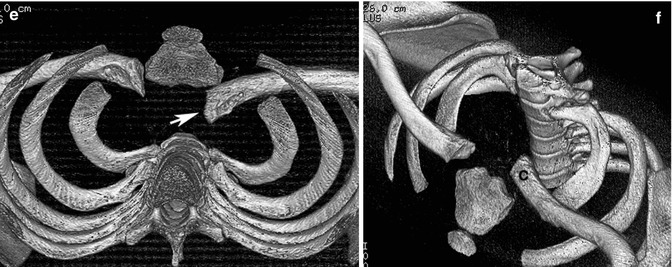

Fig. 5.5

Medial clavicular dislocation. (a) Note the slightly elevated medial left clavicle (arrow). (b) CT, coronal reconstructed view, demonstrates the slightly elevated medial left clavicle and the soft tissue bump (arrow) above it

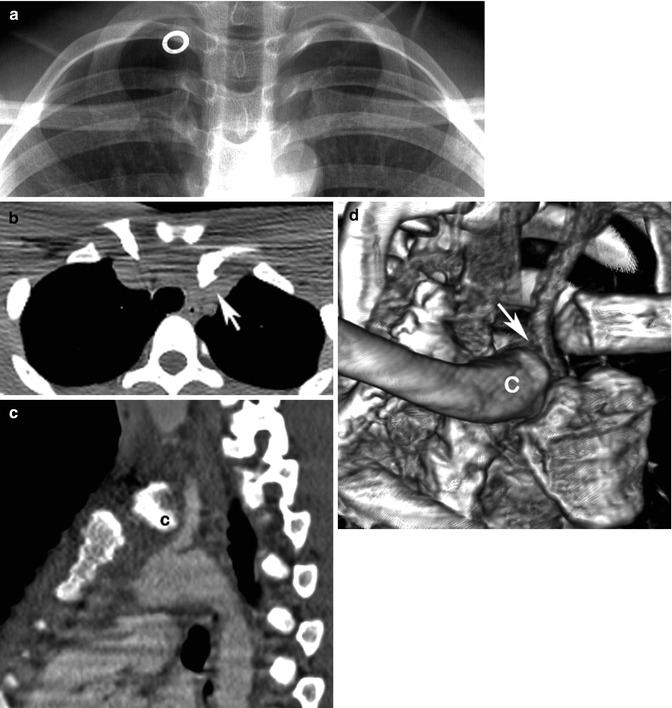

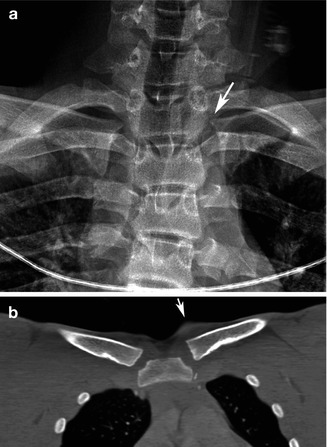

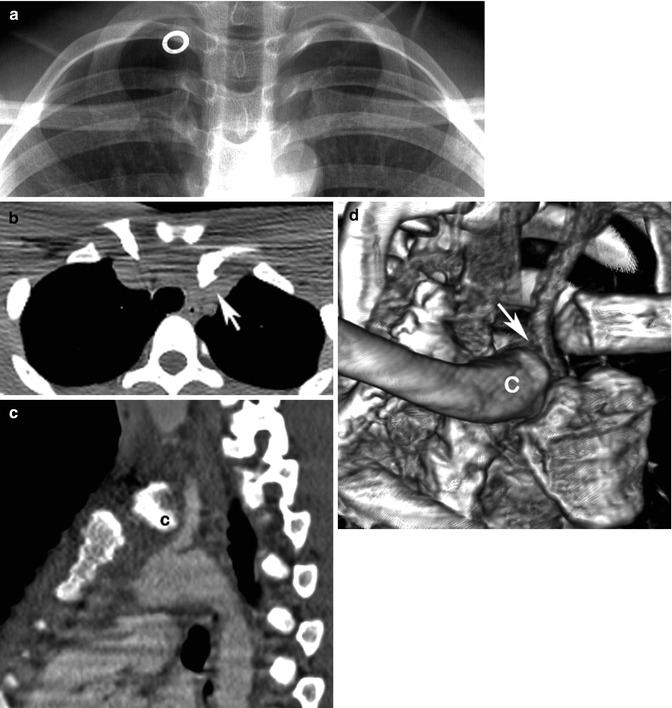

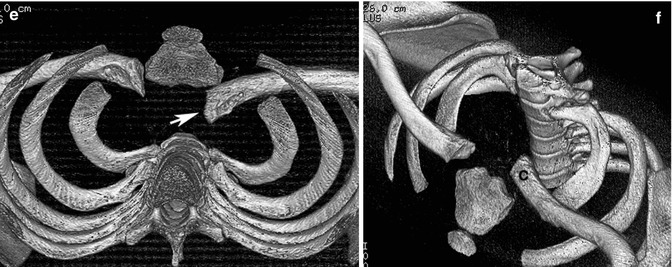

Fig. 5.6

Medial clavicular dislocation: various imaging. (a) AP view of the clavicles is normal. White circle is an artifact. (b) CT demonstrates marked posterior displacement of the left medial clavicle (arrow). (c) Sagittal reconstructed CT image demonstrates the medial end of the clavicle (C) impinging on the carotid artery. (d) 3D reconstruction demonstrates the site of impingement of the carotid artery (arrow) by the medial clavicle (C). (e) 3D reconstruction. Note the posterior position of the dislocated medial left clavicle (arrow). (f) Another view demonstrates the medial end of the clavicle (C) displaced posteriorly

Upper Humerus Injuries

In childhood, one of the more common injuries of the upper humerus is the Salter–Harris I or II epiphyseal–metaphyseal fracture. Salter–Harris type III injuries are less common and type IV and V injuries are very rare. In type I and II injuries where the epiphysis is completely separated, the diagnosis never is in doubt, but in more subtle cases, one should look for widening of the epiphyseal plate and/or a metaphyseal corner fracture (Fig. 5.7). In terms of the widened epiphyseal plate, one should be careful not to misinterpret the normal wide appearing epiphyseal plate for one which represents a fracture (Fig. 5.8).

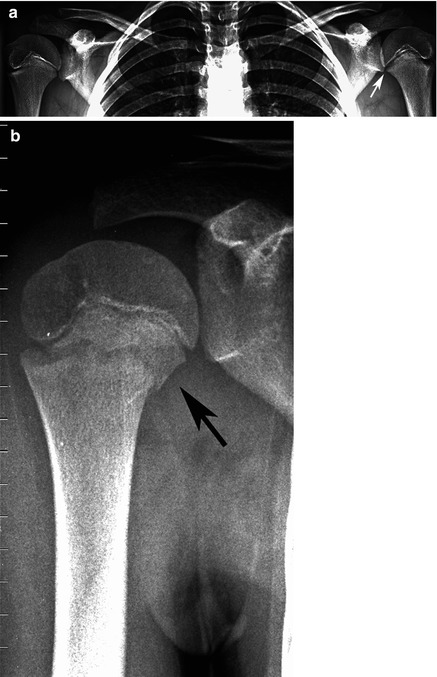

Fig. 5.7

Proximal humeral fractures. (a) Note widening of the left epiphyseal plate (arrow), consistent with a Salter–Harris I fracture. (b) In this patient, a small metaphyseal fragment (arrow) is seen consistent with a Salter–Harris II fracture