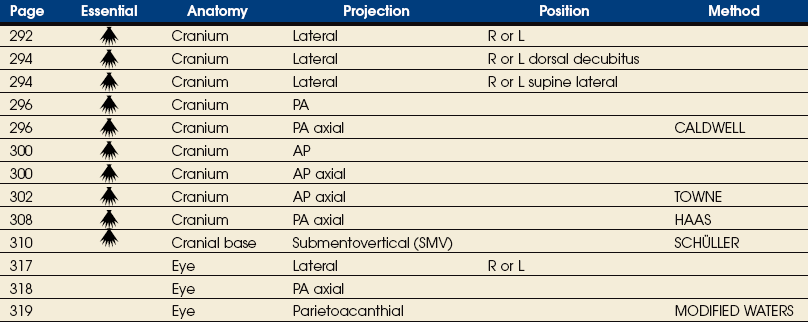

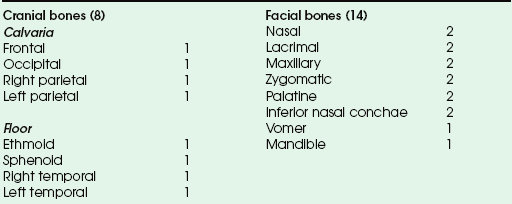

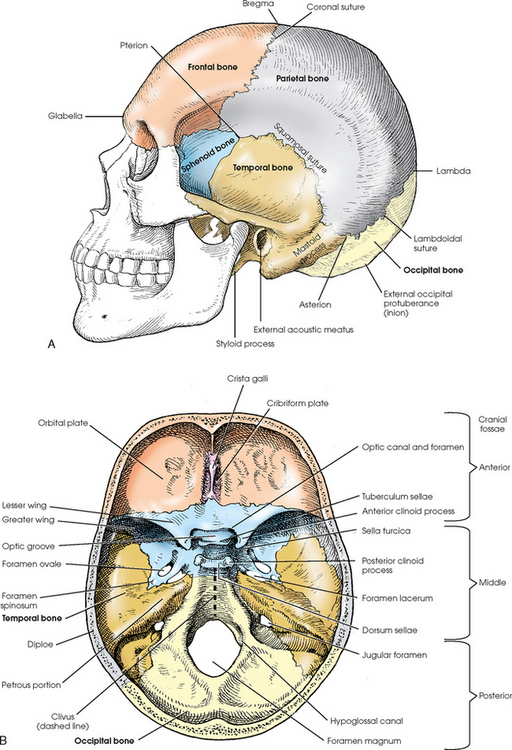

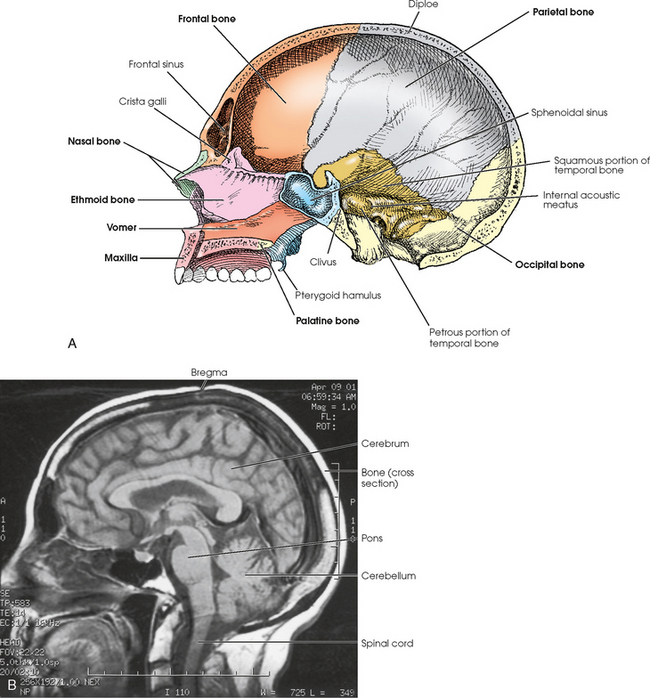

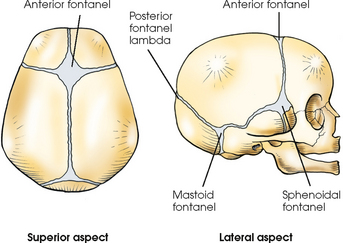

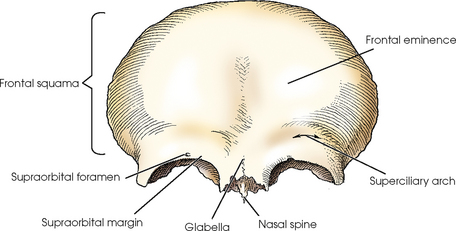

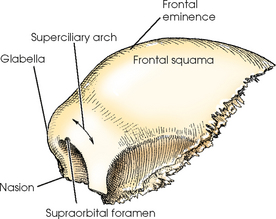

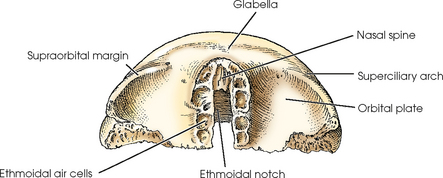

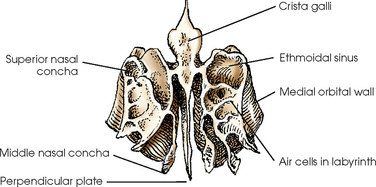

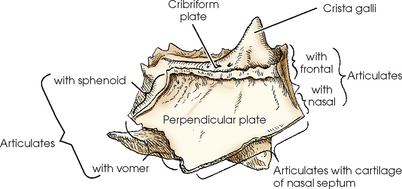

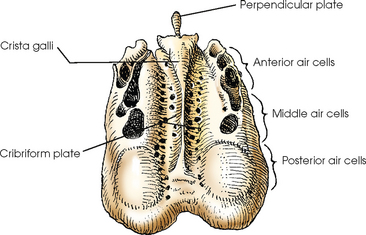

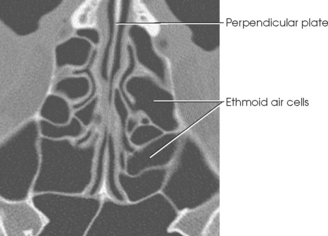

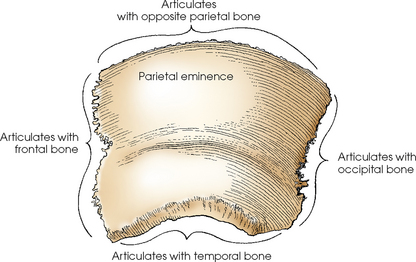

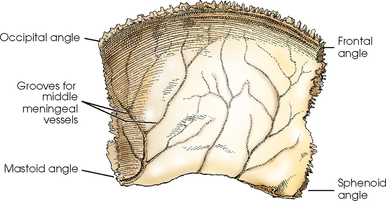

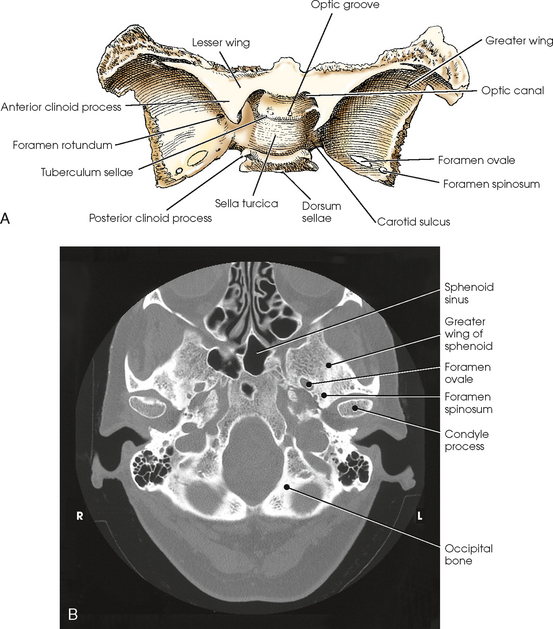

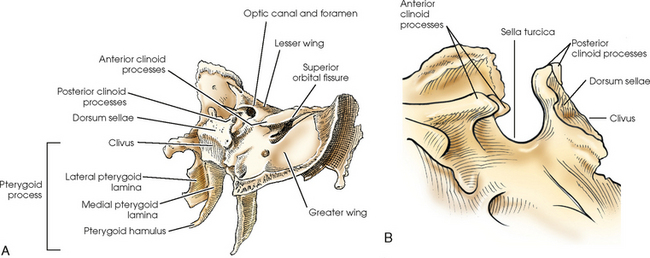

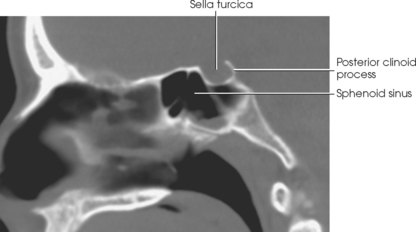

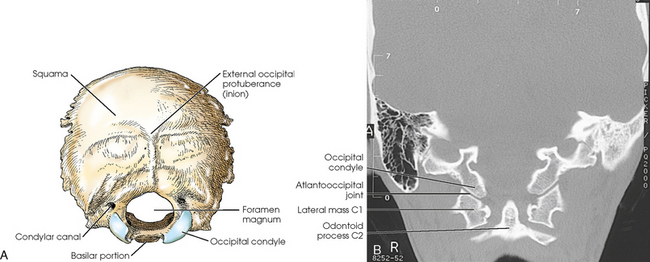

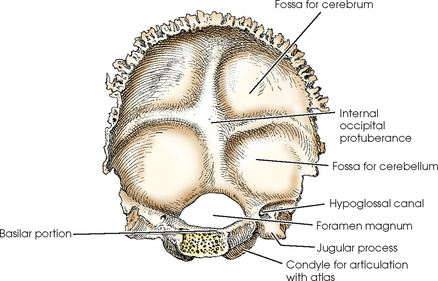

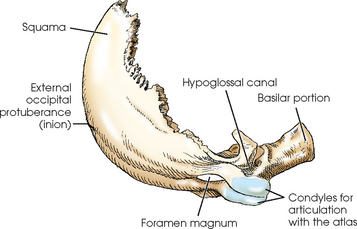

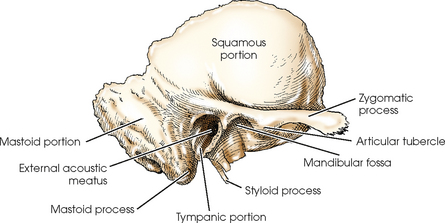

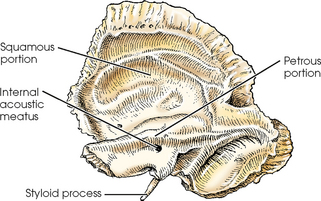

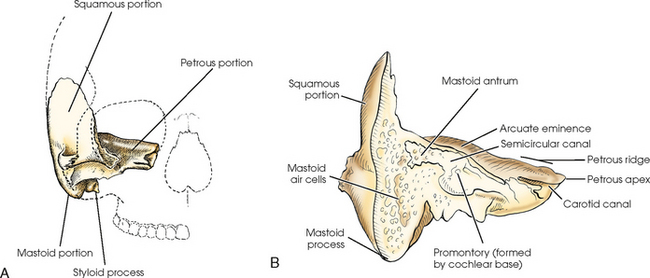

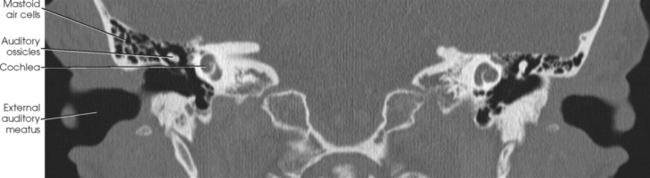

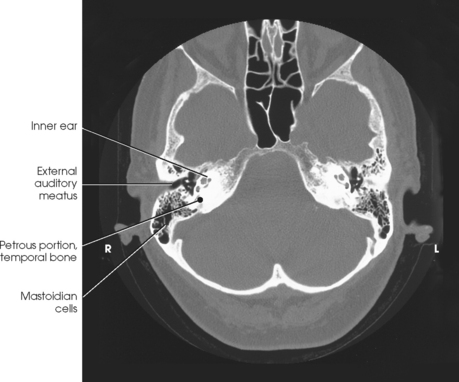

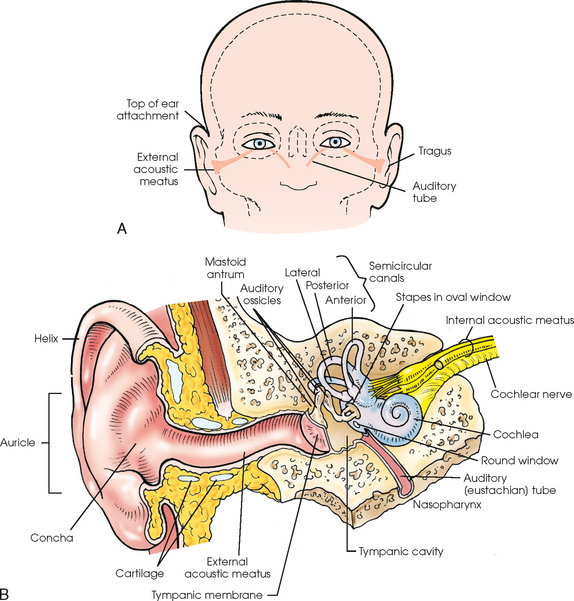

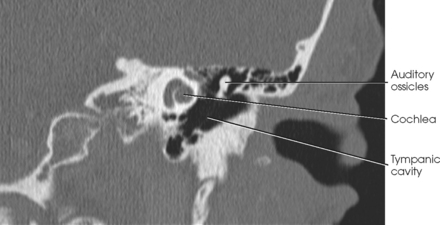

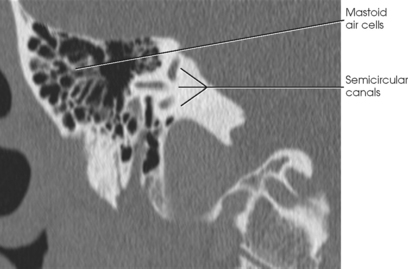

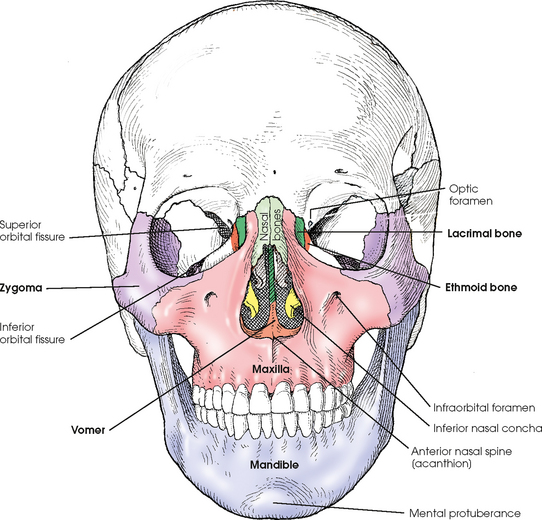

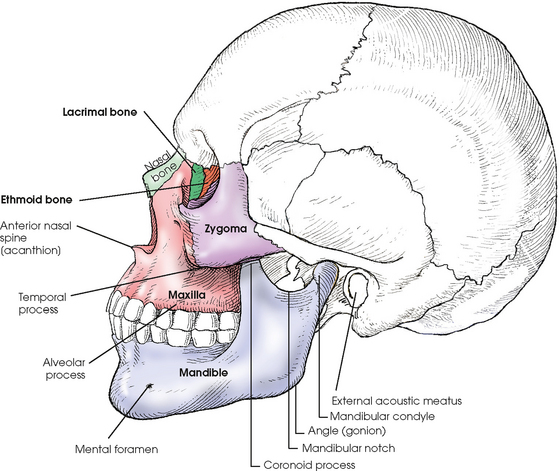

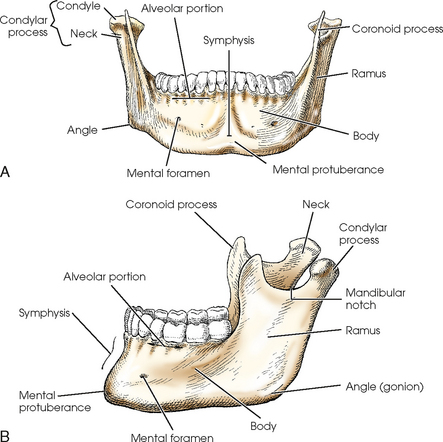

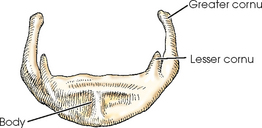

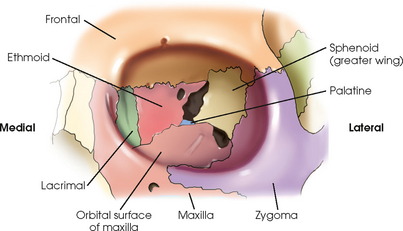

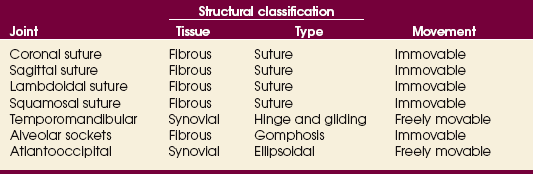

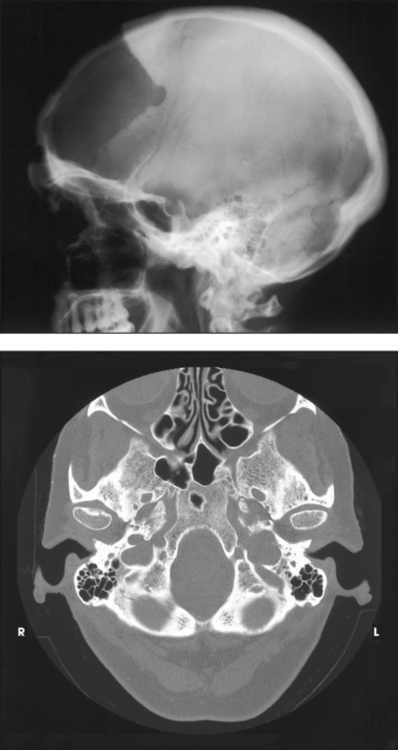

20 The skull rests on the superior aspect of the vertebral column. It is composed of 22 separate bones divided into two distinct groups: 8 cranial bones and 14 facial bones. The cranial bones are divided further into the calvaria and floor (Box 20-1). The cranial bones form a protective housing for the brain. The facial bones provide structure, shape, and support for the face. They also form a protective housing for the upper ends of the respiratory and digestive tracts and, with several of the cranial bones, form the orbital sockets for protection of the organs of sight. The hyoid bone is commonly discussed with this group of bones. The bones of the skull are identified in Figs. 20-1 to 20-3. The 22 primary bones of the skull should be located and recognized in the different views before they are studied in greater detail. The bones of the cranial vault are composed of two plates of compact tissue separated by an inner layer of spongy tissue called diploë. The outer plate, or table, is thicker than the inner table over most of the vault, and the thickness of the layer of spongy tissue varies considerably. Except for the mandible, the bones of the cranium and face are joined by fibrous joints called sutures. The sutures are named coronal, sagittal, squamosal, and lambdoidal (see Figs. 20-1 and 20-2). The coronal suture is found between the frontal and parietal bones. The sagittal suture is located on the top of the head between the two parietal bones and just behind the coronal suture line (not visible in Figs. 20-1 and 20-2). The junction of the coronal and sagittal sutures is the bregma. Between the temporal bones and the parietal bones are the squamosal sutures. Between the occipital bone and the parietal bones is the lambdoidal suture. The lambda is the junction of the lambdoidal and sagittal sutures. On the lateral aspect of the skull, the junction of the parietal bone, squamosal suture, and greater wing of the sphenoid is the pterion, which overlies the middle meningeal artery. At the junction of the occipital bone, parietal bone, and mastoid portion of the temporal bone is the asterion. In a newborn infant, the bones of the cranium are thin and not fully developed. They contain a small amount of calcium, are indistinctly marked, and present six areas of incomplete ossification called fontanels (Fig. 20-4). Two of the fontanels are situated in the midsagittal plane at the superior and posterior angles of the parietal bones. The anterior fontanel is located at the junction of the two parietal bones and the one frontal bone at the bregma. Posteriorly and in the midsagittal plane is the posterior fontanel, located at the point labeled lambda in Fig. 20-2. Two fontanels are also on each side at the inferior angles of the parietal bones. Each sphenoidal fontanel is found at the site of the pterion; the mastoid fontanels are found at the asteria. The posterior and sphenoidal fontanels normally close in the 1st and 3rd months after birth, and the anterior and mastoid fontanels close during the 2nd year of life. Internally, the cranial floor is divided into three regions: the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae (see Fig. 20-2, B). The anterior cranial fossa extends from the anterior frontal bone to the lesser wings of the sphenoid. It is associated mainly with the frontal lobes of the cerebrum. The middle cranial fossa accommodates the temporal lobes and associated neurovascular structures and extends from the lesser wings of the sphenoid bone to the apices of the petrous portions of the temporal bones. The deep depression posterior to the petrous ridges is the posterior cranial fossa, which protects the cerebellum, pons, and medulla oblongata (see Fig. 20-3, B). The frontal bone has a vertical portion and horizontal portions. The vertical portion, called the frontal squama, forms the forehead and the anterior part of the vault. The horizontal portions form the orbital plates (roofs of the orbits), part of the roof of the nasal cavity, and the greater part of the anterior cranial fossa (Figs. 20-5 to 20-7). The frontal sinuses (see Chapter 22) are situated between the two tables of the squama on each side of the midsagittal plane. These irregularly shaped sinuses are separated by a bony wall, which may be incomplete and usually deviates from the midline. The ethmoid bone is a small, cube-shaped bone that consists of a horizontal plate; a vertical plate; and two light, spongy lateral masses called labyrinths (Figs. 20-8 to 20-11). Situated between the orbits, the ethmoid bone forms part of the anterior cranial fossa, the nasal cavity and orbital walls, and the bony nasal septum. The ethmoid bone articulates with the frontal and sphenoid bones of the cranium. The two parietal bones are square and have a convex external surface and a concave internal surface (Figs. 20-12 and 20-13). The parietal bones form a large portion of the sides of the cranium. They also form the posterior portion of the cranial roof by their articulation with each other at the sagittal suture in the midsagittal plane. The sphenoid bone is an irregularly wedge-shaped bone that resembles a bat with its wings extended. It is situated in the base of the cranium anterior to the temporal bones and basilar part of the occipital bone (Figs. 20-14 to 20-16). The sphenoid bone consists of a body; two lesser wings and two greater wings, which project laterally from the sides of the body; and two pterygoid processes, which project inferiorly from each side of the inferior surface of the body. The body of the sphenoid bone contains the two sphenoidal sinuses, which are incompletely separated by a median septum. The anterior surface of the body forms the posterior bony wall of the nasal cavity. The superior surface presents a deep depression called the sella turcica and contains a gland called the pituitary gland. The sella turcica lies in the midsagittal plane of the cranium at a point ¾ inch (1.9 cm) anterior to and ¾ inch (1.9 cm) superior to the level of the external acoustic meatus (EAM). The sella turcica is bounded anteriorly by the tuberculum sellae and posteriorly by the dorsum sellae, which bears the posterior clinoid processes. The slanted area of bone posterior and inferior to the dorsum sellae is continuous with the basilar portion of the occipital bone and is called the clivus. The clivus supports the pons. On either side of the sella turcica is a groove, the carotid sulcus, in which the internal carotid artery and cavernous sinus lie. The pterygoid processes arise from the lateral portions of the inferior surface of the body of the sphenoid bone and the medial portions of the inferior surfaces of the greater wings. These processes project inferiorly and curve laterally. Each pterygoid process consists of two plates of bone, the medial and lateral pterygoid laminae, which are fused at their superoanterior parts. The inferior extremity of the medial lamina possesses an elongated, hook-shaped process, the pterygoid hamulus, which makes it longer and narrower than the lateral lamina. The pterygoid processes articulate with the palatine bones anteriorly and with the wings of the vomer, where they enter into the formation of the nasal cavity. The sphenoid bone articulates with each of the other seven bones of the cranium. The occipital bone is situated at the posteroinferior part of the cranium. It forms the posterior half of the base of the cranium and the greater part of the posterior cranial fossa (Figs. 20-17 to 20-19). The occipital bone has four parts: the squama, which is saucer-shaped, being convex externally; two occipital condyles, which extend anteriorly, one on each side of the foramen magnum; and the basilar portion. The occipital bone also has a large aperture, the foramen magnum, through which the inferior portion of the medulla oblongata passes as it exits the cranial cavity and joins the spinal cord. The occipital condyles project anteriorly, one from each side of the squama, for articulation with the atlas of the cervical spine. Part of each lateral portion curves medially to fuse with the basilar portion and complete the foramen magnum, and part of it projects laterally to form the jugular process. On the inferior surface of the curved parts, extending from the level of the middle of the foramen magnum anteriorly to the level of its anterior margin, reciprocally shaped condyles articulate with the superior facets of the atlas. These articulations, known as the occipitoatlantal joints, are the only bony articulations between the skull and the neck. The hypoglossal canals are found at the anterior ends of the condyles and transmit the hypoglossal nerves. At the posterior end of the condyles are the condylar canals, through which the emissary veins pass. The anterior portion of the occipital bone contains a deep notch that forms a part of the jugular foramen (see Fig. 20-2, B). The jugular foramen is an important large opening in the skull for two reasons: It allows blood to drain from the brain via the internal jugular vein, and it lets three cranial nerves pass through it. The temporal bones are irregular in shape and are situated on each side of the base of the cranium between the greater wings of the sphenoid bone and the occipital bone (Figs. 20-20 to 20-24). The temporal bones form a large part of the middle fossa of the cranium and a small part of the posterior fossa. Each temporal bone consists of a squamous portion, a tympanic portion, a styloid process, a zygomatic process, and a petromastoid portion (the mastoid and petrous portions) that contains the organs of hearing and balance. The petrous and mastoid portions together are called the petromastoid portion. The mastoid portion, which forms the inferior, posterior part of the temporal bone, is prolonged into the conical mastoid process (see Figs. 20-22 and 20-24). The petrous portion, often called the petrous pyramid, is conical or pyramidal and is the thickest, densest bone in the cranium. This part of the temporal bone contains the organs of hearing and balance. From its base at the squamous and mastoid portions, the petrous portion projects medially and anteriorly between the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and the occipital bone to the body of the sphenoid bone, with which its apex articulates. The internal carotid artery in the carotid canal enters the inferior aspect of the petrous portion, passes superior to the cochlea, then passes medially to exit the petrous apex. Near the petrous apex is a ragged foramen called the foramen lacerum. The carotid canal opens into this foramen, which contains the internal carotid artery (see Fig. 20-2, B). At the center of the posterior aspect of the petrous portion is the internal acoustic meatus (IAM), which transmits the vestibulocochlear and facial nerves. The upper border of the petrous portion is commonly referred to as the petrous ridge. The top of the ridge lies approximately at the level of an external radiography landmark called the top of ear attachment (TEA). The temporal bone articulates with the parietal, occipital, and sphenoid bones of the cranium. The ear is the organ of hearing and balance (Fig. 20-25). The essential parts of the ear are housed in the petrous portion of the temporal bone. The organs of hearing and equilibrium consist of three main divisions: the external ear, middle ear, and internal ear. The middle ear is situated between the external ear and internal ear. The middle ear proper consists of (1) the tympanic membrane (or eardrum); (2) an irregularly shaped, air-containing compartment called the tympanic cavity; and (3) three small bones called the auditory ossicles (Fig. 20-26). The middle ear communicates with the mastoid antrum and auditory eustachian tube. The internal ear contains the essential sensory apparatus of hearing and equilibrium and lies on the densest portion of the petrous portion immediately below the arcuate eminence. Composed of an irregularly shaped bony chamber called the bony labyrinth, the internal ear is housed within the bony chamber and is an intercommunicating system of ducts and sacs known as the membranous labyrinth. The bony labyrinth consists of three distinctly shaped parts: (1) a spiral-coiled, tubular part called the cochlea, which communicates with the middle ear through the membranous covering of the round window (see Fig. 20-26); (2) a small, ovoid central compartment behind the cochlea, known as the vestibule, which communicates with the middle ear via the oval window; and (3) three unequally sized semicircular canals that form right angles to one another and are called, according to their positions, the anterior, posterior, and lateral semicircular canals (Fig. 20-27). From its cranial orifice, the internal acoustic meatus (IAM) passes inferiorly and laterally for a distance of about ½ inch (1.3 cm). Through this canal, the cochlear and vestibular nerves pass from their fibers in the respective parts of the membranous labyrinth to the brain. The cochlea is used for hearing, and the vestibule and semicircular canals are involved with equilibrium. The two small, thin nasal bones vary in size and shape in different individuals (Figs. 20-28 and 20-29). They form the superior bony wall (called the bridge of the nose) of the nasal cavity. The nasal bones articulate in the midsagittal plane, where at their posterosuperior surface they also articulate with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. They articulate with the frontal bone above and with the maxillae at the sides. The two lacrimal bones, which are the smallest bones in the skull, are very thin and are situated at the anterior part of the medial wall of the orbits between the labyrinth of the ethmoid bone and the maxilla (see Figs. 20-28 and 20-29). Together with the maxillae, the lacrimal bones form the lacrimal fossae, which accommodate the lacrimal sacs. Each lacrimal bone contains a lacrimal foramen through which a tear duct passes. Each lacrimal bone articulates with the frontal and ethmoid cranial bones and the maxilla and inferior nasal concha facial bones. The lacrimal bones can be seen on PA and lateral projections of the skull. The two maxillary bones are the largest of the immovable bones of the face (see Figs. 20-28 and 20-29). Each articulates with all other facial bones except the mandible. Each also articulates with the frontal and ethmoid bones of the cranium. The maxillary bones form part of the lateral walls and most of the floor of the nasal cavity, part of the floor of the orbital cavities, and three fourths of the roof of the mouth. Their zygomatic processes articulate with the zygomatic bones and assist in the formation of the prominence of the cheeks. The body of each maxilla contains a large, pyramidal cavity called the maxillary sinus, which empties into the nasal cavity. An infraorbital foramen is located under each orbit and serves as a passage through which the infraorbital nerve and artery reach the nose. The zygomatic bones form the prominence of the cheeks and a part of the side wall and floor of the orbital cavities (see Figs. 20-28 and 20-29). A posteriorly extending temporal process unites with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to form the zygomatic arch. The zygomatic bones articulate with the frontal bone superiorly, with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone at the side, with the maxilla anteriorly, and with the sphenoid bone posteriorly. The two palatine bones are L-shaped bones composed of vertical and horizontal plates. The horizontal plates articulate with the maxillae to complete the posterior fourth of the bony palate, or roof of the mouth (see Fig. 20-3). The vertical portions of the palatine bones extend upward between the maxillae and the pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone in the posterior nasal cavity. The superior tips of the vertical portions of the palatine bones assist in forming the posteromedial bony orbit. The inferior nasal conchae extend diagonally and inferiorly from the lateral walls of the nasal cavity at approximately its lower third (see Fig. 20-28). They are long, narrow, and extremely thin; they curl laterally, which gives them a scroll-like appearance. The vomer is a thin plate of bone situated in the midsagittal plane of the floor of the nasal cavity, where it forms the inferior part of the nasal septum (see Fig. 20-28). The anterior border of the vomer slants superiorly and posteriorly from the anterior nasal spine to the body of the sphenoid bone, with which its superior border articulates. The superior part of its anterior border articulates with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone; its posterior border is free. The mandible, the largest and densest bone of the face, consists of a curved horizontal portion, called the body, and two vertical portions, called the rami, which unite with the body at the angle of the mandible, or gonion (Fig. 20-30). At birth, the mandible consists of bilateral pieces held together by a fibrous symphysis that ossifies during the first year of life. At the site of ossification is a slight ridge that ends below in a triangular prominence, the mental protuberance. The symphysis is the most anterior and central part of the mandible. This is where the left and right halves of the mandible have fused. The rami project superiorly at an obtuse angle to the body of the mandible, and their broad surface forms an angle of approximately 110 to 120 degrees. Each ramus presents two processes at its upper extremity, one coronoid and one condylar, which are separated by a concave area called the mandibular notch. The anterior process, the coronoid process, is thin and tapered and projects to a higher level than the posterior process. The condylar process consists of a constricted area, the neck, above which is a broad, thick, almost transversely placed condyle that articulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone (Fig. 20-31). This articulation, the TMJ, slants posteriorly approximately 15 degrees and inferiorly and medially approximately 15 degrees. Radiographic projections, produced from the opposite side, must reverse these directions. In other words, the central ray angulation must be superior and anterior to coincide with the long axis of the joint. The TMJ is situated immediately in front of the EAM. The hyoid bone is a small, U-shaped structure situated at the base of the tongue, where it is held in position in part by the stylohyoid ligaments extending from the styloid processes of the temporal bones (Fig. 20-32). Although the hyoid bone is an accessory bone of the axial skeleton, it is described in this chapter because of its connection with the temporal bones. The hyoid is the only bone in the body that does not articulate with any other bone. Each orbit is composed of seven different bones (Fig. 20-33). Three of these are cranial bones: frontal, sphenoid, and ethmoid. The other four bones are the facial bones: maxilla, zygoma, lacrimal, and palatine. The circumference of the orbit, or outer rim area, is composed of three of the seven bones—the frontal, zygoma, and maxilla. The remaining four bones compose most of the posterior aspect of the orbit. The sutures of the skull are connected by toothlike projections of bone interlocked with a thin layer of fibrous tissue. These articulations allow for no movement and are classified as fibrous joints of the suture type. The articulations of the facial bones, including the joints between the roots of the teeth and the jawbones, are fibrous gomphoses. The exception is the point at which the rounded condyle of the mandible articulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone to form the TMJ. The TMJ articulation is a synovial joint of the hinge and gliding type. The atlantooccipital joint is a synovial ellipsoidal joint that joins the base of the skull (occipital bone) with the atlas of the cervical spine. The seven joints of the skull are summarized in Table 20-1.

SKULL

Skull

Cranial Bones

ETHMOID BONE

PARIETAL BONES

SPHENOID BONE

OCCIPITAL BONE

TEMPORAL BONES

Petromastoid portion

Ear

MIDDLE EAR

INTERNAL EAR

Facial Bones

LACRIMAL BONES

MAXILLARY BONES

ZYGOMATIC BONES

PALATINE BONES

INFERIOR NASAL CONCHAE

VOMER

MANDIBLE

HYOID BONE

ORBITS

Articulations of the Skull