Chapter 16 Small Bowel Malignant Tumors

Introduction

Small bowel (SB) malignancies account for only 2% of all gastrointestinal (GI) neoplasms and less than 0.4% of all cancers in the United States.1 Common malignant tumors of the SB include primary adenocarcinoma, carcinoid, lymphoma, GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumor), and metastases. Recent increases in the incidence of carcinoid tumors have now made carcinoids the most common primary SB tumor: carcinoid 44%, adenocarcinoma 33%, sarcomas 17%, and lymphoma 8%.2 The risk of a specific SB tumor type depends on the exact location in the SB, with adenocarcinomas the most common duodenal tumor, carcinoids the most common ileal tumor, and both sarcoma and lymphoma more equally distributed throughout the entire SB. The clinical presentation of SB tumors is nonspecific with abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, GI bleeding, and SB obstruction the most common symptoms.3 Endoscopic evaluation of the SB has been hampered by the long length of the SB, approximately 5 to 6 m. However, recent advances in endoscopic technologies, such as push enteroscopy, video capsule endoscopy, and double-balloon enteroscopy, have allowed the evaluation of the entire SB.4–6

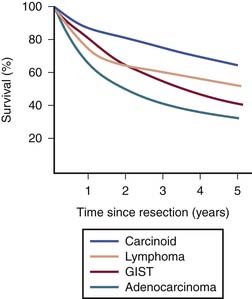

Heterogeneous biology of SB tumors is reflected in survival, being lowest for adenocarcinoma and highest for carcinoid (Figure 16-1). Owing to substantial differences in clinical and imaging features,7–9 the most common malignancies of the SB including adenocarcinoma, carcinoid, GIST, lymphoma, and metastases are discussed in this chapter as separate entities.

I Adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Adenocarcinoma for decades has been the most common malignant tumor of the SB, recently surpassed by carcinoid. Currently, adenocarcinoma is the second most common primary malignancy of the SB (33% of all primary SB tumors). One of the more interesting aspects of small intestine adenocarcinoma is its rarity in comparison with large intestine adenocarcinoma. Despite the small intestine representing approximately 70% to 80% of the length and over 90% of the surface area of the alimentary tract, the incidence of SB adenocarcinoma is 30- to 50-fold less than that of colon adenocarcinoma.10 Theories to explain the small intestine’s relative protection from the devolvement of carcinoma center around two concepts: (1) the rapid turnover time of small intestinal cells results in epithelial cell shedding before the necessary acquisition of multiple genetic defects, and (2) exposure to the carcinogenic components of our diet are limited owing to a rapid SB transit time, lack of bacterial degradation activity, and a relatively dilute, alkaline environment of the SB.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Most cases of adenocarcinoma are sporadic, with a male predominance. The incidence of SB adenocarcinoma peaks in the seventh and eighth decades, with an average age of 65 years. An increased incidence is associated with the genetic cancer syndromes of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, Peutz-Jeghers, and familial adenomatous polyposis. Inflammatory bowel disease, and in particular Crohn’s disease, is a risk factor with risk correlated with both the extent and the duration of SB involvement. Additional risk factors include personal history of colorectal cancer, celiac disease, and the ingestion of smoked or salt-cured foods.11,12

Anatomy and Pathology

Most frequently, the tumor occurs within the duodenum (49%), particularly around the papilla of Vater, and with decreasing frequency in the jejunum (21%) and ileum (15%).13 In Crohn’s disease–associated cases, 70% of tumors present in the distal ileum.

There are four histologic types of adenocarcinoma: well, moderately, and poorly differentiated, and undifferentiated.7 Prognostic factors consistently associated with poor outcome include the presence of metastatic disease, noncurative surgical resection, poor differentiation, and advanced age.2 In patients who have had surgical resection, the pathologic factors associated with increased risk of relapse include lymph node involvement, positive surgical margins, poor tumor differentiation, T4 tumor stage, and lymphovascular spread.2,13,14 As with colorectal cancer, adenocarcinoma of the SB undergoes a similar phenotypic adenoma-carcinoma transformation. Both increased size of SB adenomas and the presence of villous histology are risk factors for the development of invasive adenocarcinoma. The molecular understanding of SB adenocarcinoma is limited, although mutations in both the K-ras oncogene and the tumor suppressor gene p53 are common.15

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of SB adenocarcinoma are nonspecific and frequently do not occur until advanced disease is present. A delay in diagnosis is common, with one report demonstrating an average delay from first symptom to diagnosis of 4 months.16 The most commonly reported symptoms are abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and GI bleeding. The presenting stage distribution is stage I in 12%, stage II in 30%, stage III in 26%, and stage IV in 32%.2 Adenocarcinoma of the proximal duodenum involving the ampulla of Vater may present with obstructive jaundice.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Adenocarcinomas spread via lymphatics to the regional mesenteric lymph nodes; the most common sites of hematogenous spread are the liver and lung. Owing to the advanced stage of presentation for most patients, peritoneal carcinomatosis is also common. After a curative resection, the pattern of failure for SB adenocarcinoma is predominantly systemic with the most common sites being liver in 67%, lung in 38%, retroperitoneum in 29%, and peritoneal carcinomatosis in 25%.14

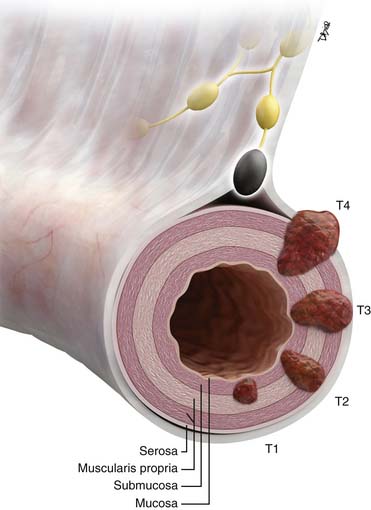

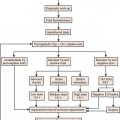

Staging Evaluation (Table 16-1 and Figure 16-2)

Key Points Staging of small bowel adenocarcinoma

• T staging: based on depth of tumor penetration into and beyond the SB wall. Imaging is contributory for T3 and T4 tumors.

• N staging by imaging: limited by an overlap in appearance of benign reactive and metastatic mesenteric lymph nodes.

• M staging: liver and lung metastases best appreciated on cross-sectional imaging. Peritoneal carcinomatosis is commonly unmeasurable by imaging.

Table 16-2 Proposed Staging System for Small Bowel Carcinoid Tumors

| STAGE | CHARACTERISTICS OF TUMOR-NODE-METASTASIS CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM |

|---|---|

| T T1 T2 T3 | Primary Tumor <2 cm up to the muscularis propria >2 cm up to the muscularis propria or < 2 cm propria beyond muscularis propria >2 cm beyond muscularis propria |

| N N0 N1 | Regional Lymph Nodes No regional lymph node metastasis present Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M M0 M1 | Distant Metastases No distant metastasis present Distant metastasis |

| STAGE | GROUPING |

| I II III IV | T1, N0-N1, M0 T2, any N, M0 T3, any N, M0 Any T, any N, M1 |

From Landry CS, et al. A proposed staging system for small bowel carcinoid tumors based on an analysis of 6,380 patients. Am J Surg. 2008;196:896-903; discussion 903.

Imaging

Tumor Detection

Enteroclysis has been a standard invasive imaging modality before the introduction of video capsule endoscopy to better evaluate SB loops.17 The sensitivity of enteroclysis is as high as 95% with 90% correct estimation of the actual size of the tumor.18

Conventional cross-sectional imaging with multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can scan the entire SB, but can be limited by lack of optimal opacification of the entire GI tract. Newer imaging techniques based on MDCT, such as MDCT enterography and MDCT enteroclysis, share advantages and disadvantages of both conventional enteroclysis and cross-sectional imaging. MDCT enterography is a noninvasive study performed without nasojejunal cannulation, which achieves good or excellent SB distention with negative oral contrast such as water or mannitol substituted for positive contrast media such as barium or gastrografin.19 MDCT enteroclysis is a relatively new technique more sensitive than conventional barium studies and less invasive than enteroscopy.20,21 Lesions as small as 5 mm can be identified.20

SB tumors may be demonstrable on routine MRI.22 MRI enteroclysis is an evolving technique capable of demonstrating an SB abnormality,23,24 with a reported sensitivity of 86%, a sensitivity of 98%, and an accuracy of 97%.

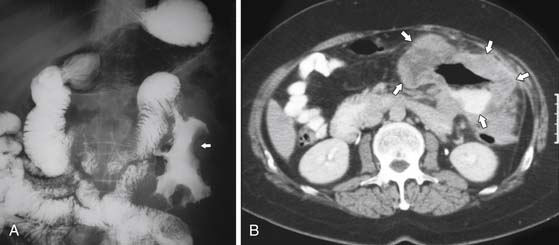

On barium studies such as standard SB series and enteroclysis, the tumor is seen as a short, circumferentially narrowed segment with overhanging borders, an “apple-core” lesion (Figure 16-3).

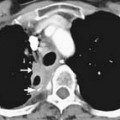

On computed tomography (CT), adenocarcinomas typically appear as a focal area of wall thickening causing luminal narrowing25 (Figure 16-4). These tumors are often rigid and fibrotic and, therefore, result in early obstruction, although infiltrative lesions without narrowing have also been reported (Figure 16-5).

Ulceration, present in 40% of pathologic specimens, is not reliably visualized on CT.

Adenocarcinomas complicating longstanding Crohn’s disease generally arise in the distal ileum. These tumors are difficult to detect because of a preexisting abnormality causing thickening and retraction of the bowel, deforming normal anatomy and masking early diagnosis.

Metastatic Disease (M)

Key Points The imaging report for small bowel adenocarcinoma

• Location and size of the primary tumor, if detectable by imaging.

• Tumorous involvement of adjacent vascular structures, which may preclude resection. This is particularly critical for duodenal adenocarcinoma, potentially involving superior mesenteric vessels and the portal vein.

• Size and number of the regional mesenteric lymph nodes.

• Presence of distant metastases in the liver or lungs. Presence of ascites is suspicious for peritoneal carcinomatosis until proved otherwise and can be confirmed by fluid cytology. Peritoneal spread commonly presents as ascites rather than measurable discrete omental implants.

Treatment

Wide segmental resection with regional mesenteric lymphadenectomy is the standard approach for both treatment and staging purposes. In the case of adenocarcinoma involving the proximal duodenum, pancreaticoduodenectomy may be required.26 Curative radical surgery is the most important prognostic factor.27

The role of adjuvant therapy for SB adenocarcinoma has not been well delineated, with no prospective or retrospective studies having demonstrated a benefit of adjuvant therapy. Despite this lack of data, adjuvant chemotherapy, generally utilizing a combination of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and oxaliplatin, is often used in patients at high risk for relapse. In addition, for patients with curatively resected adenocarcinoma of the duodenum, adjuvant 5-FU-based chemoradiation has been utilized to reduce the risk of local failure.27 Locally advanced unresectable tumors and metastatic tumors are treated with chemotherapy, most commonly 5-FU combined with either oxaliplatin or irinotecan. Median survival for patients with metastatic disease is approximately 12 to 18 months.28,29 The overall survival for SB adenocarcinoma remains poor, with 5-year disease-specific survival of 65% for stage I, 48% for stage II, 35% for stage III, and 4% for stage IV.30

Key Points Treatment of small bowel adenocarcinoma

• Radical curative surgery is the most desired approach when not precluded by preoperative proof of distant metastases. Duodenal adenocarcinoma requires pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s surgery). Limited detection of peritoneal spread and military liver metastases by imaging sometimes leads to the need for diagnostic laparoscopy as the first step before attempted curative resection.

• Adjuvant chemoradiation based on 5-FU is used to decrease the risk of local recurrence.

• 5-FU-based chemotherapy for unresectable disease has a low response rate with a poor 5-year survival of 4% at stage IV.

Anatomy and Pathology

Macroscopically, carcinoid tumors are present as small submucosal nodules, often subcentimeter in size, not causing obstruction of the lumen per se, with intense desmoplastic response within the adjacent mesentery. Thirty percent of SB carcinoids have multicentric disease at diagnosis.31 Although much rarer than carcinoid tumors, intermediate- and high-grade neuroendocrine tumors, characterized by both a higher rate of mitotic activity and tumor necrosis, can also arise in the SB. These tumors have a more aggressive biology, with high-grade neuroendocrine tumors of the SB behaving like small cell carcinomas of the lung.

Key Points Anatomy and pathology of carcinoid

• Carcinoid is a well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma.

• Microscopically, carcinoid is composed of uniform small cells containing neurosecretory granules, with bioactive products such as serotonin, somatostatin, glucagon, histamine, or gastrin.

• Macroscopically, carcinoid tumors are often small submucosal nodules, multifocal in 30% of cases, with intense desmoplastic response within the adjacent mesentery.

Clinical Presentation

Because of their indolent growth, most SB carcinoids are asymptomatic and identified incidentally. Generally, symptoms from SB carcinoids relate to either mass effect from the primary or metastatic tumors or from hypersecretion of bioactive products such as serotonin. One third of midgut carcinoids are symptomatic with abdominal pain or bowel obstruction, and only 10% are associated with carcinoid syndrome. The carcinoid syndrome is primarily seen in the context of liver metastases, in which the release of serotonin gains access to the systemic circulation without undergoing hepatic metabolism.32 Carcinoid syndrome consists of secretory diarrhea, bouts of cutaneous flushing, wheezing, and dyspnea due to bronchospasm. Longstanding carcinoid syndrome may cause fibrotic changes in the cardiac valves predominantly affecting the right heart, typically leading to tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic stenosis. A 24-hour urinary collection for the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) has both good sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of the carcinoid syndrome.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

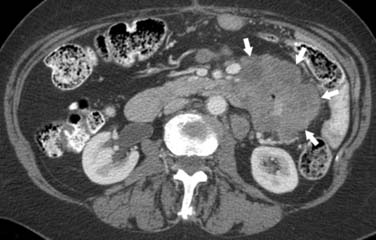

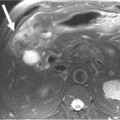

Tumorous spread via lymphatics into the mesenteric lymph nodes induces extensive desmoplastic reaction leading to retraction of the mesentery, kinking and obstruction of the mesenteric veins, and retraction and mechanical obstruction of the surrounding SB loops (Figure 16-6). This mesenteric nodal metastasis produces a typical mesenteric mass detectable by CT, as opposed to the small primary tumor that is commonly too small to detect by imaging.

Key Points Patterns of tumor spread of carcinoid

• Lymphatic spread to mesenteric lymph nodes is associated with desmoplastic reaction causing retraction of the mesentery, potentially leading to bowel obstruction.

• Hematogenous spread to the liver may be associated with the development of carcinoid syndrome.

• Peritoneal metastases are commonly small and rarely cause ascites.

Staging Evaluation

A revised TNM staging for carcinoid tumors, which is slightly different from the TNM staging of SB adenocarcinoma, has recently been proposed33 (Table 16-2).

Table 16-1 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging for Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma

| STAGE | CHARACTERISTICS OF TUMOR-NODE-METASTASIS CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM |

|---|---|

| T TX T0 Tis T1a T1b T2 T3 T4 | Primary Tumor Primary tumor cannot be assessed No evidence of primary tumor present Carcinoma in situ Tumor invades the lamina propria Tumor invades the submucosa Tumor invades the muscularis propria. Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into subserosa or into nonperitonealized perimuscular tissue (mesentery or retroperitoneum), with extension of < 2 cm Tumor penetrates the visceral peritoneum or directly invades other organs or structures |

| N NX N0 N1 N2 | Regional Lymph Nodes Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed No regional lymph node metastasis Regional lymph node metastasis with one to three lymph nodes involved Regional lymph node metastasis with four or more lymph nodes involved |

| M MX M0 M1 | Distant Metastases Presence of distant metastasis cannot be assessed No distant metastasis Distant metastasis |

| Stage | Grouping |

| 0 I IIA IIB IIIA IIIB IV | Tis, N0, M0 T1-T2, N0, M0 T3, N0, M0 T4, N0, M0 Any T, N1, M0 Any T, N2, M0 Any T, any N, M1 |

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:127-129.

Key Point Staging of carcinoid

• The TNM staging of carcinoid is similar to that of adenocarcinoma, with the exception of T staging including not only the depth of invasion into the bowel wall but also a size as a separate criterion. Two centimeters serves as a threshold, with tumors larger than 2 cm upstaged in T status to T3, having a worse prognosis.

Imaging

CT may identify the submucosal carcinoid tumor as a small mural mass with early intense contrast enhancement due to hyperemia.34 Hyperenhancing tumor can be best appreciated on the background of negative contrast in the bowel lumen in the arterial phase of contrast injection (Figures 16-7 and 16-8). Classic mesenteric nodal metastasis of carcinoid has a nearly pathognomonic CT pattern as a spiculated soft tissue density mesenteric mass due to desmoplastic reaction34,35 (Figures 16-9 and 16-10). Sometimes, a longer segment of adjacent SB has a thickened edematous wall due to mesenteric venous engorgement (see Figure 16-10). Calcification within the mesenteric extension can be seen in up to 70% of cases (see Figure 16-9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree