Chapter 7 Small Vessel Disease

Small vessel disease is the less understood of the major mechanisms of cerebral ischemia. This is the case despite its high prevalence in the elderly population, in whom it can present in the form of lacunar strokes, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cognitive decline.1

The seminal work of Dr. C. M. Fisher based on his clinicopathological observations led to the definition of lacunar strokes as small subcortical infarcts measuring between 3 mm and 2 cm and caused by the occlusion of penetrating branches of cerebral arteries.2 He described lipohyalinosis, a hypertensive microvasculopathy, as the main anatomical substrate for the development of lacunar infarctions and also deep cerebral hemorrhages.3 However, he recognized that plaques of atheroma in the parent vessel occluding the origin of the penetrating branch4 and probably microembolism (in patients with structurally normal penetrating branch corresponding to the area of small infarction and a systemic cause of embolism)4 could also produce lacunar strokes. He characterized the classic lacunar syndromes but noted that a number of atypical clinical presentations could also occur. He was then well aware of the fact that small vessel disease does not constitute a uniform disorder but rather may result from a complex spectrum of conditions with various clinical manifestations.

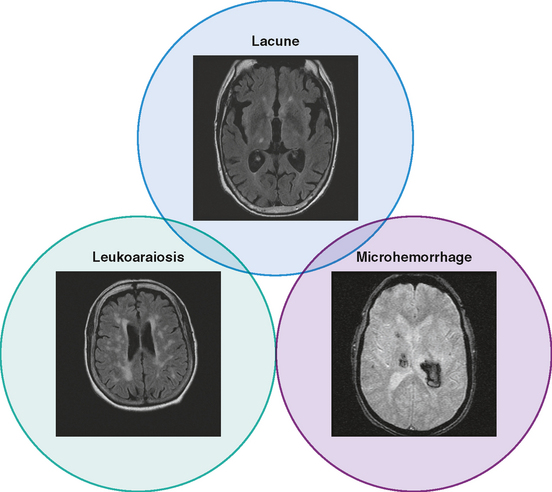

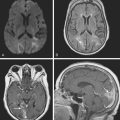

Unfortunately, the conceptualization of lacunar strokes became quite simplified and dogmatic (and therefore untrue) over time. Lacunar infarctions had to manifest with one of the traditional “lacunar syndromes,” they had to be less than 15 mm in size, they only happened in hypertensive patients, and they were always caused by “small vessel disease” (typically understood as lipohyalinosis according to what became known as the “lacunar hypothesis”). However, the advent of brain imaging techniques came to prove that these general assumptions cannot be always applied. First, computed tomography (CT) scan and most recently and especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have reactivated research on this topic by uncovering the real dimension of the intricate disorder we now call small vessel disease to include small subcortical infarctions, microhemorrhages, and white matter changes (also known as leukoaraiosis for the rarefaction of the white matter seen on pathological specimens) (Figure 7-1).

Longitudinal studies using serial MRI scans are shedding light on the incidence, progression, and severity of cognitive decline in patients with white matter disease. As a consequence, vascular dementia is emerging as a major public health concern.5 Neuroimaging is replacing pathology in the study of the pathophysiology of small vessel strokes, a remarkable indication of progress because small subcortical strokes are not fatal and therefore pathological examinations only allow the examination of chronic lesions. In fact, new theories defying the preeminence of lipohyalinosis have been postulated to explain the genesis of small subcortical strokes.6,7 Additionally, hemosiderin-sensitive sequences (such as gradient recall echo) allow visualization of areas of microhemorrhage, which were previously impossible to diagnose in vivo.8,9

SMALL SUBCORTICAL INFARCTIONS

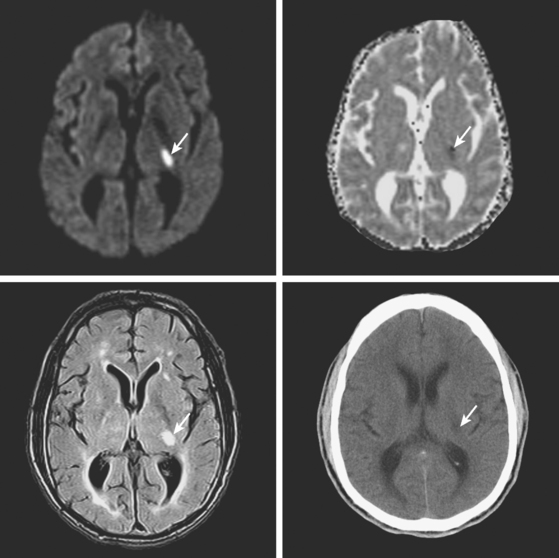

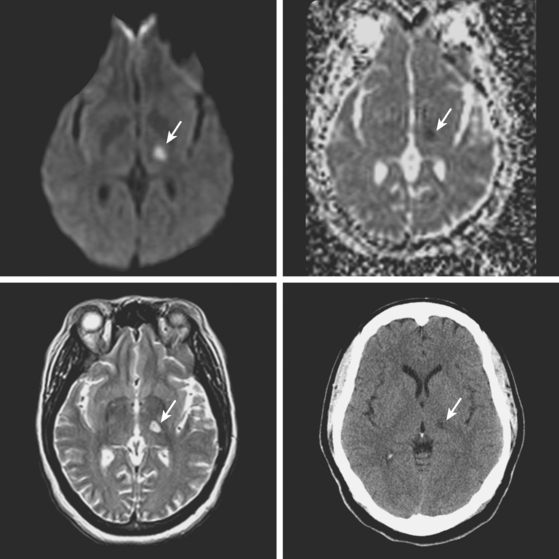

A 78-year-old man with history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes awoke with inability to move his right side. On examination, his blood pressure was 180/98, his pulse was regular, and he had no carotid bruits. He had a dense right hemiparesis with no other associated neurological deficits. Initial CT of scan of the head did not reveal any acute intracranial abnormalities. Brain MRI (Figure 7-2) showed an acute small subcortical stroke in the posterior limb of the left internal capsule. Carotid ultrasound and cardiac workup were unremarkable. The patient was discharged on antiplatelet therapy, antihypertensives, an adjusted regimen for his diabetes, and a statin. He evolved favorably over the subsequent few months.

LACUNAR SYNDROMES

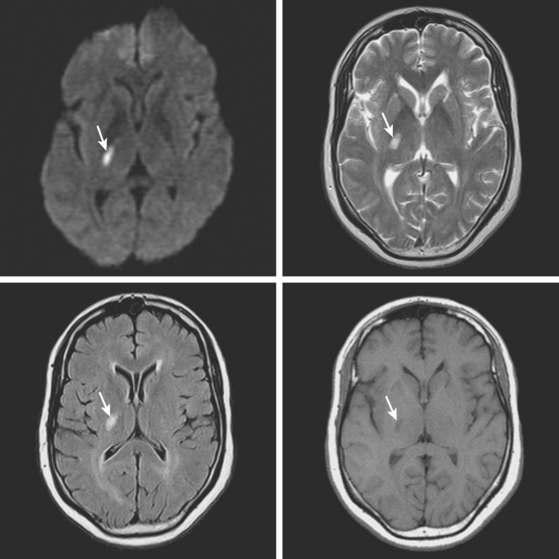

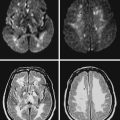

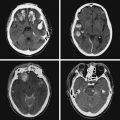

A 72-year-old obese woman with history of hypertension and metabolic syndrome presented with acute onset of right-sided numbness and weakness. Symptoms had started the day before, but she had not come to the emergency department because they had fluctuated in severity to the point that a few times she felt almost back to normal. However, over the previous 6 to 8 hours before her arrival to the emergency department, her deficits had become constant. Examination demonstrated right hemiparesis and hypoesthesia without associated cortical signs. Brain imaging confirmed the clinical suspicion that the patient had a small subcortical stroke (Figure 7-5) that had presented with an initially stuttering course. Her deficits improved over the following days, and she had nondisabling residual motor and sensory sequelae 3 months later.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree