Pierre E. Bize • Yann Lachenal • Alban Denys

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) has proven to be useful in the treatment of hemodynamically stable polytrauma patients.1,2 It has also proven to be useful in selected hemodynamically unstable patients who responded at least transiently to fluid resuscitation.3,4 However, the place of TAE in the treatment algorithm of polytrauma patients remains to be defined.5–12 TAE has several advantages in selected trauma patients. It can control several sources of bleeding from one single vascular puncture, avoiding unnecessary surgical exposure in those fragile patients, thus avoiding hypothermia, which is often a problem in this setting. It can be performed in the angiography suite while other resuscitation maneuvers are carried on. It can be performed without major risks in patients with impaired coagulation, which is also quite frequent in polytranfused patients. As opposed to solid organ or pelvic bone fractures, there is little information on the role of TAE in the treatment of paraspinal bleeding associated with spine trauma or with fractures of other bones such as in the limbs.13–21

DEVICE AND MATERIALS

Bleeding associated with spine or bone fractures is usually of osseous or venous origin and is self-limited. However, some cases of bleeding from an arterial injury can be associated with significant blood loss. Arterial bleeding in the paraspinal space and in the limbs may have originated from muscular branches and thus can be embolized with gelatin sponge or even glue. Particulate agents such as Bead Blocks (Biocompatible, Farnham UK) are not usually recommended because they might cause ischemia and rhabdomyolysis. Coils are convenient when there is a single well-identified vessel that can be selectively catheterized, such as the intercostal or the lumbar arteries. However, when using coils, one should use the “front door/back door” embolization technique to prevent further bleeding from retrograde flow. This technique consists of placing the coil beyond and before the vascular lesion. However, glue and gelatin sponge are perfectly suitable in this particular situation, with the advantage of being able to control the bleeding from both the antegrade and retrograde flow more quickly and at a lower cost.

TECHNIQUE

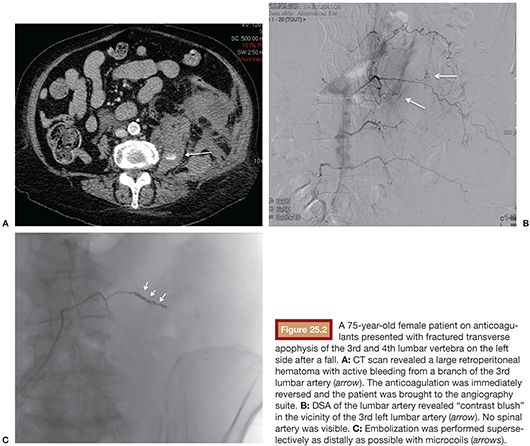

The target vessel should be identified from the computed tomography (CT) with contrast as it might be difficult to identify bleeding vessels by digital subtraction angiography (DSA) in hypotensive patients. Arterial access is gained usually from one of the common femoral arteries. When bleeding from a lower limb is present and other vessels need to be embolized, it is best to choose the contralateral common femoral artery and to catheterize the bleeding side by crossover. Antegrade puncture of the common femoral artery on the bleeding side is not convenient as it will render catheterization of other bleeding vessels uneasy if not impossible. In case of nonpalpable pulse, ultrasound guidance should be used promptly. The Seldinger technique is used to gain vascular access, and a 5-Fr or 6-Fr introducer sheath is inserted in the common femoral artery. The choice of catheter curvature will depend on the vessel to be embolized. A Cobra C2 (Glidecath, Terumo Europe, Leuven Belgium) catheter usually allows catheterization of the lumbar arteries and also allows crossover to the contralateral iliac and femoral arteries. Vascular anomalies such as irregular vessel walls, dissection, pseudoaneurysm, or active bleeding should be looked for by selective catheterization using a 4-Fr or 5-Fr catheter. If no abnormality and no active bleeding is seen in the suspected vascular territory, a forceful hand injection can reveal the bleeding from an injured vessel, which was occluded by spasm, dissection, or clot. In case of superselective catheterization, a microcatheter allowing the use of 0.018-in coils should be used. In case of embolization of a lumbar artery with coils, care should be taken to embolize the lumbar arteries above and below the bleeding level to avoid retrograde filling of the embolized artery by collateral flow from the upper and lower levels.

In the paraspinal space, always look for spinal arteries, especially in the dorsolumbar region. The anterior and posterior spinal arteries supply the spinal cord. The anterior spinal artery receives blood from a large segmental vessel originating from one of the last intercostal arteries known as the Adamkiewicz artery (typically located between the vertebral bodies T8–L2 segment). The posterior spinal artery receives many segmental feeders known as the radiculospinal arteries, which can be recognized by their “hairpin” shape on angiography (Fig. 25.1). When present, embolization should take place from beyond the origin of the radiculospinal artery. Coils or large gelatin sponge torpedoes are best used in this situation. If particulate agents are to be used, they should be greater than 350 µm in size.22

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

TAE of arterial bleeding associated with spine or peripheral bone fracture can be convenient in patients with other bleeding sites that also need to be treated by embolization or in patients with altered coagulation status. One typical scenario is a patient with a ruptured spleen associated with rib and lumbar transverse apophysis fractures. Another scenario would be a patient with a fractured bone and an impaired coagulation status. TAE could resolve the hemorrhage quickly while the coagulation status is restored before reparative surgery.

Bleeding in the Paraspinal Space

In trauma patients, bleeding in the paraspinal space is usually associated with vertebral fractures. Paraspinal bleeding originates mostly from the broken bone itself or from the azygos and hemiazygos veins and perispinal venous plexuses. These bleeding sources are not amenable to embolization, but they are usually self-limiting.19 However, bleeding in the paraspinal space when associated with bleeding in other territories can lead to significant blood loss.21,23 Care should be taken to look for an arterial bleeding source when interpreting a CT scan in a polytrauma patient with a significant hematoma in the paraspinal space. In the absence of other sources of bleeding such as the renal or the internal iliac arteries and their branches, the most frequently involved arteries in this setting are the intercostal and lumbar arteries.21,23,24 If the bleeding vessel can be identified from multislice CT imaging, TAE can be used to control bleeding in the paraspinal space. TAE is particularly useful in patients with other bleeding sites. As it is the case for abdominal organ lesions, a good CT with arterial enhancement and multiplanar reconstruction will guide the embolization procedure and make it quicker and easier, avoiding the time-consuming catheterization of all lumbar and pelvic arteries. Figure 25.2 displays the case of a woman on anticoagulants with a vertebral fracture and paraspinal hematoma with active bleeding treated by TAE. Another interesting use of TAE is the treatment of bleeding from penetrating wounds such as stab wounds or gunshot wounds.1,18,25 When surgery is not absolutely mandatory, such as in case of hollow viscus perforation, TAE can avoid surgery and quickly control bleeding from the injured vessels. Figure 25.3 displays the case of a patient who sustained a stab wound in the paraspinal region and was treated by TAE only.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree