Anatomy

The spleen is an intraperitoneal organ located just below the diaphragm in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. It is protected laterally by the ribs and it borders on the stomach, the left kidney, the left lobe of the liver, and the left colic flexure. The pancreatic tail often extends into the splenic hilum. The normal spleen measures 4 cm × 7 cm × 11 cm and weighs an average of 150 g (range of ca. 100–250 g). The spleen is held in place by two fibrous peritoneal attachments, the gastrosplenic ligament and splenorenal ligament. Because of these attachments, mechanical manipulations can lead to injury of the splenic capsule. 1

The spleen derives its blood supply from the splenic artery, which arises from the celiac trunk and often runs a very tortuous course along the superior border of the pancreas to the splenic hilum. Before entering the spleen, the splenic artery usually divides into several branches that pierce the splenic capsule separately, accompanied by veins. 1

Trabeculae emerge from the fibrous capsule and extend into the spleen, subdividing the splenic parenchyma and forming a framework that contains the red and white pulp. Arterial blood from the trabecular arteries, located within the trabeculae, flows through the white pulp, which contains lymphoid follicles, and is channeled from there to the red pulp, which is permeated by sinusoidal veins. 1 This unique architecture imparts a heterogeneous “tiger stripe” appearance to the splenic parenchyma on CT and MR images acquired in the arterial phase, when enhancement occurs predominantly in the white pulp (see ▶ Fig. 9.1, ▶ Fig. 9.2). 2 This pattern should not be mistaken for pathology. With images acquired in the venous phase, on the other hand, enhancement occurs predominantly in the red pulp, creating a homogeneous appearance on sectional images.

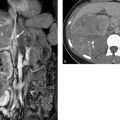

Fig. 9.1 CT of the upper abdomen. (a) CT scan acquired in the arterial phase of enhancement. The spleen has a typical inhomogeneous “tiger stripe” appearance. (b) CT scan in the venous phase of enhancement. The spleen has a homogeneous appearance.

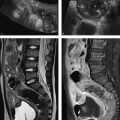

Fig. 9.2 MRI of the upper abdomen at 3.0 T. This patient is known to have partial portal vein thrombosis (not shown). This condition slows the blood flow through the spleen, delaying the enhancement dynamics of the splenic parenchyma. Standard T1W and T2W sequences are shown along with enhancement dynamics. Images in the dynamic series (b–f) were acquired at approximately 30-second intervals. (a) Fat-saturated T2W TSE sequence. (b) Unenhanced T1W 3D GRE sequence. (c) Early arterial T1W 3D GRE sequence. (d) Late arterial T1W 3D GRE sequence. (e) Early venous T1W 3D GRE sequence. (f) Late venous T1W 3D GRE sequence.

Consistent with its role in the immune system, some hematopoiesis (lymphocytes and plasma cells) takes place within the spleen. Another function of the spleen is the removal of old, damaged erythrocytes from the circulation. 1 It also functions as a reservoir for blood storage.

Note

The normal dimensions of the spleen are 4 cm × 7 cm × 11 cm.

Caution

Inhomogeneous enhancement of the spleen on arterial-phase images is normal.

9.2.2 Imaging

Radiography

Because of the lack of soft tissue contrast, conventional radiographs are not useful for evaluating the spleen.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is considered the standard modality for initial imaging evaluation of the spleen (▶ Fig. 9.3). It can be used to determine the size and shape of the spleen, evaluate parenchymal lesions, and exclude injuries. 3

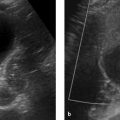

Fig. 9.3 Ultrasound scan of a normal spleen. Transcostal ultrasound scan in a 39-year-old man displays the spleen in its greatest longitudinal dimension. The scan also depicts the splenic vein in the splenic hilum (arrow). The spleen in this patient measures approximately 13 cm, but this is not considered abnormal given the otherwise normal configuration of the organ (homogeneous parenchyma, tapered borders).

The spleen should be scanned with a low-frequency probe (e.g., 3.5 MHz) with the patient in the supine position. Because splenic ultrasound requires an intercostal approach, it may be helpful to have the patient elevate the arm to spread the ribs apart. Due to the subphrenic location of the spleen and the presence of air in the costodiaphragmatic recess, it is often difficult to define all portions of the spleen with ultrasound. The acoustic window can be optimized by scanning at end expiration or during slow expiration. 3

Computed Tomography

CT usually permits a more precise evaluation of the spleen than ultrasound owing to its high spatial resolution and because it is independent of acoustic windows and the experience of the examiner.

Because of its vascular architecture, the spleen shows a very inhomogeneous enhancement pattern (▶ Fig. 9.1) when imaged in the arterial phase approximately 30 seconds after IV bolus injection. A normal spleen will then show homogeneous enhancement when imaged in the portal venous phase approximately 60 to 90 seconds after bolus injection.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is useful for the further characterization of focal lesions detected in the spleen, for example by differentiating metastases and hemangiomas. The iron content of the spleen can also be evaluated with MRI, which is useful in the quantification of hemochromatosis.

The full range of sequences ordinarily used for upper abdominal imaging can also be used for the spleen:

T1W and fat-saturated T2W sequences to bring out anatomical details.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences and enhancement dynamics for identification and characterization of lesions (▶ Fig. 9.2), e.g., for differentiating metastases, hemangiomas, and cysts.

T2*W GRE sequences and double-echo sequences to evaluate splenic iron content.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) techniques to evaluate the vessels supplying and draining the spleen.

9.2.3 Anomalies and Normal Variants

Accessory Spleen

Brief definition Approximately 30% of individuals have one or more small accessory spleens (up to approximately 4 cm in diameter) in addition to the main spleen. Accessory spleens are usually located close to the spleen, e.g., in the gastrosplenic ligament, splenic hilum, or greater omentum (▶ Fig. 9.4). 4 An accessory spleen consists of ectopic splenic tissue that has developed apart from the main spleen.

Fig. 9.4 Accessory spleen. Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen in a 68-year-old man (coronal reformatted image). An accessory spleen (arrow) is noted in the splenic hilum as an incidental finding.

Imaging signs Accessory spleens have the same density or intensity as the main spleen in sectional imaging studies.

Clinical features Accessory spleens are not pathologic in the true sense. The majority are asymptomatic, although a few may become symptomatic due to torsion and rupture.

Differential diagnosis

Splenosis (implantation of ectopic splenic tissue in the peritoneal cavity after abdominal trauma or surgery; ▶ Fig. 9.5). 5

Tumors (e.g., pancreatic, adrenal, renal, or gastric).

Metastases (especially peritoneal deposits).

Polysplenia.

Fig. 9.5 Splenosis in a 53-year-old man who had a splenectomy in his youth because of abdominal trauma. The current CT examination was for staging of rectal carcinoma. Besides the opacified stomach (long arrows), the image shows a rounded mass in the left upper quadrant (short arrow) consistent with a focus of splenosis.

Pitfalls An accessory spleen may be misinterpreted as a malignant mass.

Note

An accessory spleen should be considered whenever an intraparietal mass is discovered close to the spleen.

Asplenia and Polysplenia

Brief definition Very rarely, and usually in association with other congenital anomalies (fetal heterotaxy syndrome), the spleen may be congenitally absent (asplenia in right isomerism) or may consist of multiple unfused spleens (polysplenia in left isomerism). 6, 7 Some authors also define splenectomy as a form of asplenia.

Imaging signs

Asplenia syndrome (right isomerism): bilateral right-sidedness. Asplenia may be accompanied by a number of other anomalies such as severe, usually cyanotic cardiac anomalies, bilateral trilobed lungs, esophageal varices, gastric hypoplasia or duplication, annular pancreas, Hirschsprung’s disease, anal atresia, ectopic liver and gallbladder, and urogenital tract anomalies. Approximately 80% of affected children die before 1 year of age.

Polysplenia syndrome (left isomerism): Besides multiple small spleens, patients often have severe cardiac anomalies, bilateral bilobed lungs, esophageal or duodenal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistulas, pancreatic anomalies, duplicated stomach, and short bowel syndrome or malrotation. There is frequent intrahepatic interruption of the inferior vena cava with azygos continuation. With an approximately 50% mortality rate before age 1 year, polysplenia syndrome has a somewhat better prognosis than asplenia syndrome, but only 10% of affected children survive to adolescence.

Clinical features Polysplenia and asplenia in the setting of heterotaxy syndromes are associated with cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, and hepatic anomalies.

Differential diagnosis If there are no additional anomalies, a diagnosis of polysplenia or asplenia is unlikely. Polysplenia requires differentiation from splenosis and multiple accessory spleens. Prior splenectomy should be included in the differential diagnosis of asplenia.

Pitfalls There is a risk of confusing splenosis or accessory spleens with polysplenia.

9.2.4 Diseases

Differential Diagnosis of Splenomegaly

Brief definition Splenomegaly refers to abnormal enlargement of the spleen.

Imaging signs As noted earlier, the normal dimensions of the spleen are 4 cm × 7 cm × 11 cm. Nevertheless, significant variations of physiologic splenic size may be encountered in practice. Even spleens with a greatest dimension of 12 or 13 cm may still be considered normal, depending on the patient’s constitution. Splenomegaly is diagnosed when the volume of the spleen is 500 cm3 or more. 5 As well as sheer size, it is also important to evaluate the morphology of the spleen. The poles of a normal spleen are sharply tapered, whereas they are rounded and blunted in splenomegaly (▶ Fig. 9.6).

Fig. 9.6 Splenomegaly. CT of the upper abdomen in a 54-year-old man with hepatosplenomegaly in a setting of osteomyelofibrosis. The spleen has a slightly inhomogeneous, nodular appearance with rounded surface contours. Collaterals have developed in the splenic hilum and perigastric region (arrows) in response to portal hypertension. The displacement and deformation of the left kidney underscores the chronic nature of the disease.

Clinical features Splenomegaly in itself is usually asymptomatic. Very large spleens may exert a mass effect on adjacent structures. Otherwise the clinical findings depend on the cause of the splenomegaly.

Differential diagnosis Splenomegaly may have a variety of causes. It is helpful to divide the potential causes into five etiologic categories 5, 8:

Congestion: congestion may be due, for example, to portal vein or splenic vein thrombosis, hepatic cirrhosis, diffuse high-grade tumor invasion of the liver, hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd–Chiari syndrome), or right heart failure. Imaging in these cases shows portocaval anastomoses as evidence of portal hypertension (dilatation of the splenic and portal veins, esophageal and fundic varices, recanalized umbilical vein with a caput medusae, splenorenal shunts, shunting via the hepatic and splenic capsule, and so on; ▶ Fig. 9.7, ▶ Fig. 9.8).

Fig. 9.7 Alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver. Abdominal CT in a 53-year-old man. Coronal reformatted image with venous contrast enhancement shows numerous signs of portal hypertension: splenomegaly, varicose anastomoses about the splenic hilum (short arrow), esophageal varices (short dashed arrow), thickening of the cecal wall due to congestive enteropathy (long dashed arrow), increased density of the mesenteric root due to fluid permeation (long arrow), and some perihepatic ascites.

Fig. 9.8 Alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver. Abdominal CT in a 43-year-old man. Coronal reformatted image with venous contrast enhancement shows a nodular liver surface, splenomegaly, and ascites.

Hematologic: possible causes of splenomegaly in this category are leukemias, hemoglobinopathies, polycythemia vera, and osteomyelofibrosis. The underlying cause is a redistribution of hematopoietic bone marrow from the medullary cavities to the spleen.

Inflammatory or infectious: viral infections such as mononucleosis, HIV, and tuberculosis as well as granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and rheumatoid disorders may be associated with splenomegaly. Viral infections may incite a general immune activation, causing a relatively homogeneous splenomegaly, whereas granulomatous diseases often cause a nodular infiltration of the spleen with possible associated calcifications. Splenomegaly may be a permanent condition after certain viral diseases (typically Epstein–Barr virus).

Masses: splenomegaly due to lymphoma, metastases, or cysts. Malignant infiltration of the spleen may be a unifocal, multifocal, or diffuse process (see ▶ Fig. 9.9, ▶ Fig. 9.10, ▶ Fig. 9.11). Cysts are a rare cause of splenomegaly.

Deposition disorders: hemochromatosis, amyloidosis, and other storage diseases can lead to splenomegaly.

Fig. 9.9 Splenic involvement by lymphoma in a 41-year-old man who underwent allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia and Epstein–Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative disease. Abdominal CT in the venous phase shows hypodense splenic lesions with faint margins (long arrow) and heterogeneous enhancement of the liver with periportal edema, consistent with lymphomatous involvement. There is also ascites (short arrows).

Fig. 9.10 Splenic involvement by lymphoma in a 67-year-old woman with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Axial CT of the upper abdomen demonstrates focal splenic involvement (arrow).

Fig. 9.11 Splenic involvement by lymphoma in a 57-year-old man with marginal zone lymphoma. Coronal reformatted abdominal CT image with venous contrast enhancement shows diffuse infiltration of the spleen with splenomegaly (white arrow) accompanied by homogeneous bone marrow infiltration in both femurs (black arrows).

Pitfalls A slightly enlarged spleen with a normal shape may be mistaken for splenomegaly.

Key points Splenomegaly may have hemodynamic, hematologic, infectious/immunologic, oncologic, or deposition-related causes.

Note

Look for signs of portal hypertension when splenomegaly is present.

Splenic Infarction

Brief definition Splenic infarction results from the segmental (frequent) or global (rare) infarction of arterial vessels in the splenic parenchyma. Possible causes are emboli (atrial fibrillation, atherosclerosis, foreign bodies, septic embolism), hematologic disorders with increased cellularity or coagulability, and specific changes that can cause splenomegaly. 9

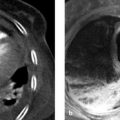

Imaging signs Splenic infarcts usually appear as peripheral wedge-shaped areas on sectional images (▶ Fig. 9.12). They are hypodense on contrast-enhanced CT and are frequently isoechoic on ultrasound. Acute infarcts on MRI are hyperintense in T2W sequences due to the presence of hemorrhage and edema. Chronic infarcts are usually hypointense. Over time there may be a regression of affected regions with capsular constriction, and cysts may also form (see ▶ Fig. 9.13).

Fig. 9.12 Splenic infarction in a 63-year-old man with left upper quadrant pain. Abdominal CT with venous contrast enhancement shows a hypodense, wedge-shaped perfusion defect in the spleen (arrows) with no parenchymal scarring or constriction. This finding is most consistent with an acute splenic infarction.

Fig. 9.13 Calcified splenic cyst in a 67-year-old man. Abdominal CT incidentally detects a splenic defect with a rim-calcified cystic lesion (arrows), most likely secondary to a partial infarction of the spleen that occurred years earlier. The differential diagnosis would also include previous splenic trauma. Multiple hepatic lesions and a left pleural effusion are also noted as incidental findings. (a) Axial CT scan. (b) Coronal reformatted image with venous contrast.

Clinical features Acute splenic infarction may be manifested by upper abdominal pain. There may also be periembolic symptoms such as fever and chills. 10 These symptoms are self-limiting and should last no longer than one week. As a rule, there is no need for treatment. Splenectomy may be considered if symptoms are severe.

Differential diagnosis The differential diagnosis of splenic infarction should include abscesses, masses, cysts, and splenic injury.

Pitfalls A splenic infarct may be mistaken for a laceration of the spleen.

Key points Splenic infarcts typically appear as peripheral, wedge-shaped parenchymal lesions.

Note

A possible embolic source should be investigated in all cases of suspected splenic infarction.

Splenic Cysts

Brief definition An etiologic distinction is made between (true) dysontogenetic cysts and secondary (acquired) cysts. Dysontogenetic cysts result from an error of mesothelial migration and have an endothelial cyst wall. 5 They comprise approximately 10 to 25% of all splenic cysts. 11 Acquired cysts, on the other hand, usually develop from infarcts or colliquative hematomas and have a fibrous wall. Dysontogenetic and acquired cysts are not distinguishable by imaging, and such a distinction would have no clinical implications in most patients.

Imaging signs Cysts typically have a thin wall and smooth margins. Ultrasound shows an echo-free mass with posterior acoustic enhancement. CT shows well-circumscribed hypodense lesions that do not enhance after IV injection of contrast medium (▶ Fig. 9.14). Hemorrhagic cysts may show uniform high attenuation on CT (▶ Fig. 9.15). Mural calcification is occasionally noted in splenic cysts (▶ Fig. 9.13).

Fig. 9.14 Splenic cyst discovered during melanoma staging in a 35-year-old woman. Abdominal CT with venous contrast enhancement shows a well-circumscribed, homogeneous lesion of the spleen (arrow) with no peripheral rim enhancement and fluid-equivalent attenuation values (comparable to gastric contents), most consistent with a dysontogenetic cyst.

Fig. 9.15 Hemorrhagic splenic cyst in a 66-year-old woman with chronic myeloid leukemia and acute thrombocytopenia resulting in poor coagulation status. The patient suffered a cerebral hemorrhage several days before the examination. Whole-body CT shows splenomegaly and a hyperattenuating splenic cyst with intracystic hemorrhage, most likely due to the patient’s hemorrhagic diathesis.

Clinical features Splenic cysts are usually asymptomatic. Large cysts may exert capsular tension that causes upper abdominal pain. Over time, splenic cysts may undergo intracystic hemorrhage, rupture, or infection. Symptomatic cysts are treated surgically.

Differential diagnosis

Abscesses and echinococcal cysts (usually thick-walled).

Metastases (usually show enhancement).

Infiltration by lymphoma (usually shows enhancement, indistinct margins).

Intrasplenic pseudocysts (arising from the pancreatic tail; associated signs of pancreatitis).

Key points Splenic lesions with smooth margins and fluid attenuation are usually cysts.

Splenic Abscess

Brief definition A splenic abscess is a localized collection of pus within the splenic capsule. Formation of abscesses in the spleen is most commonly due to hematogenous spread from a primary focus such as infectious endocarditis. Another potential cause is superinfection of cysts, infarcts, or hematomas. The main causative organisms are bacteria, fungi, and parasites (echinococci).

Imaging signs Splenic abscesses appear as rounded lesions with indistinct margins and peripheral enhancement. Abscesses are hypoechoic on ultrasound with ill-defined margins and internal echoes. The lesions are hypodense on CT with non-water-equivalent attenuation values. Often they have an intensely enhancing rim that has undergone inflammatory changes (▶ Fig. 9.16, ▶ Fig. 9.17). Echinococcal cysts in particular, as well as bacterial abscesses, appear as loculated lesions with internal septa and possible fine mural calcifications. The septa are usually well defined by ultrasound but often are not visualized on CT. Gas inclusions (from anaerobes) are occasionally detectable within abscesses.

Fig. 9.16 Splenic abscesses in an immunosuppressed 61-year-old man (status post bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia). Coronal reformatted image from abdominal CT with venous contrast, performed for localization of an infectious focus, shows multiple faint hypodensities in the spleen surrounded by areas of slightly increased enhancement (arrows), consistent with abscesses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree