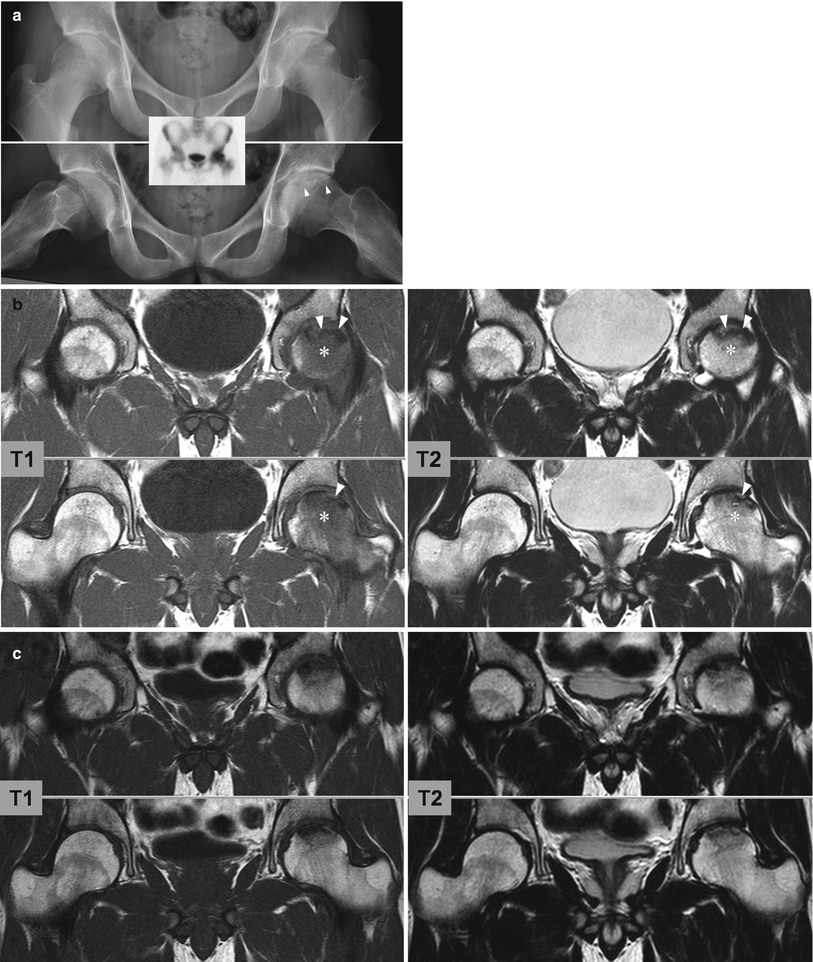

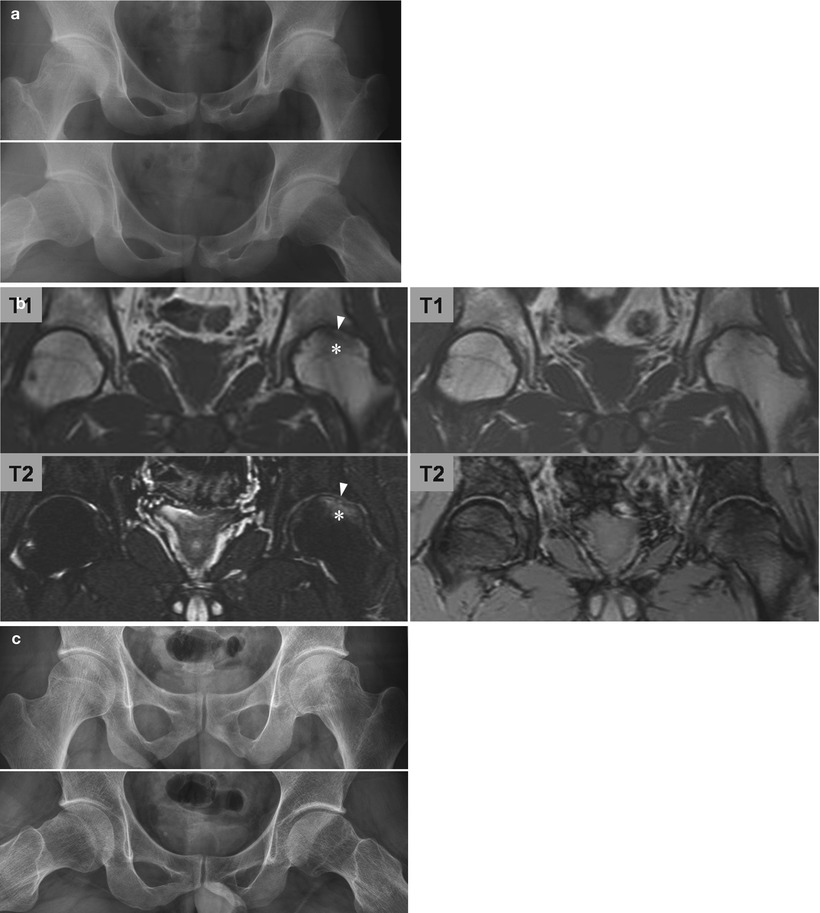

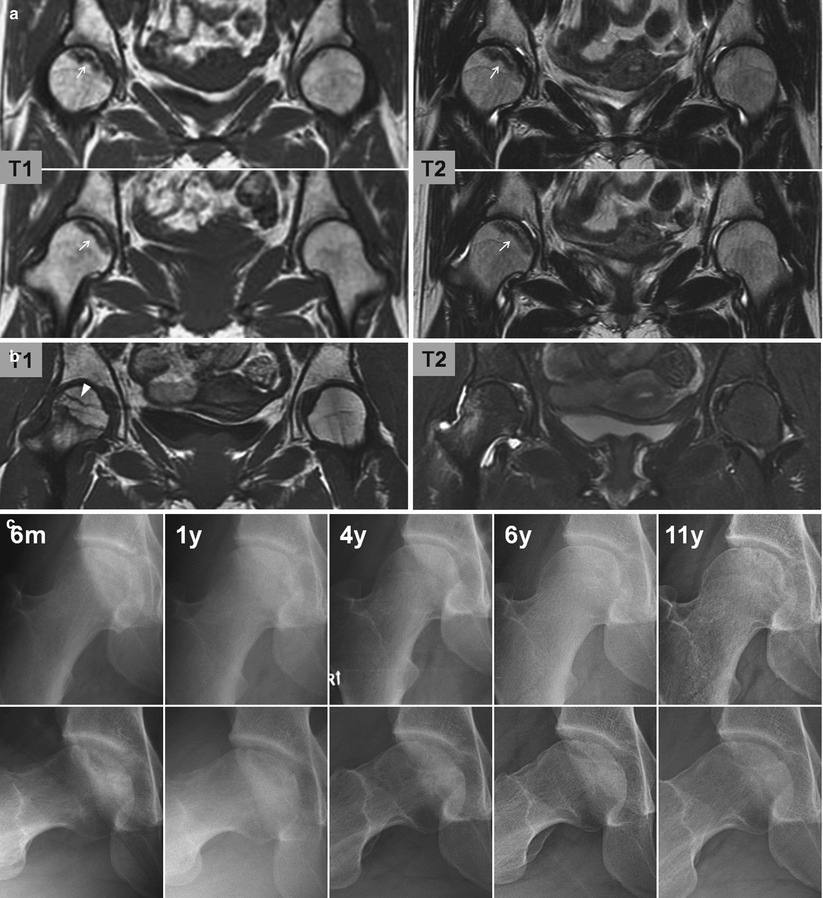

Fig. 29.1

A 27-year-old man with bilateral fatigue-type subchondral stress fracture of the femoral head. (a) Plain radiographs taken 2 weeks after the onset of both left and right hip pain show linear increased density lesion in both femoral heads and collapse of the right femoral head. (b) MR images of the hip show a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads) and bone marrow edema pattern (asterisks) extending to the subchondral area. (c) Radiographs taken 3 years after restoring right femoral head collapse using a fibular allograft demonstrate that the fracture is healed with partial restoration of the collapse

In any type of fractures, common clinical findings include hip pain and limping of sudden onset without any antecedent trauma. The pain is aggravated with activity and improves with rest. Pain and limping decrease gradually as the fracture heals. In young patients, pain disappears completely 3–9 months after pain onset even in the cases with femoral head collapse [29, 41, 43]. However, in insufficiency-type fracture in elderly patients, incomplete resolution of pain is frequent and half of the cases need total hip arthroplasty [32, 45, 52].

29.3 Image Findings

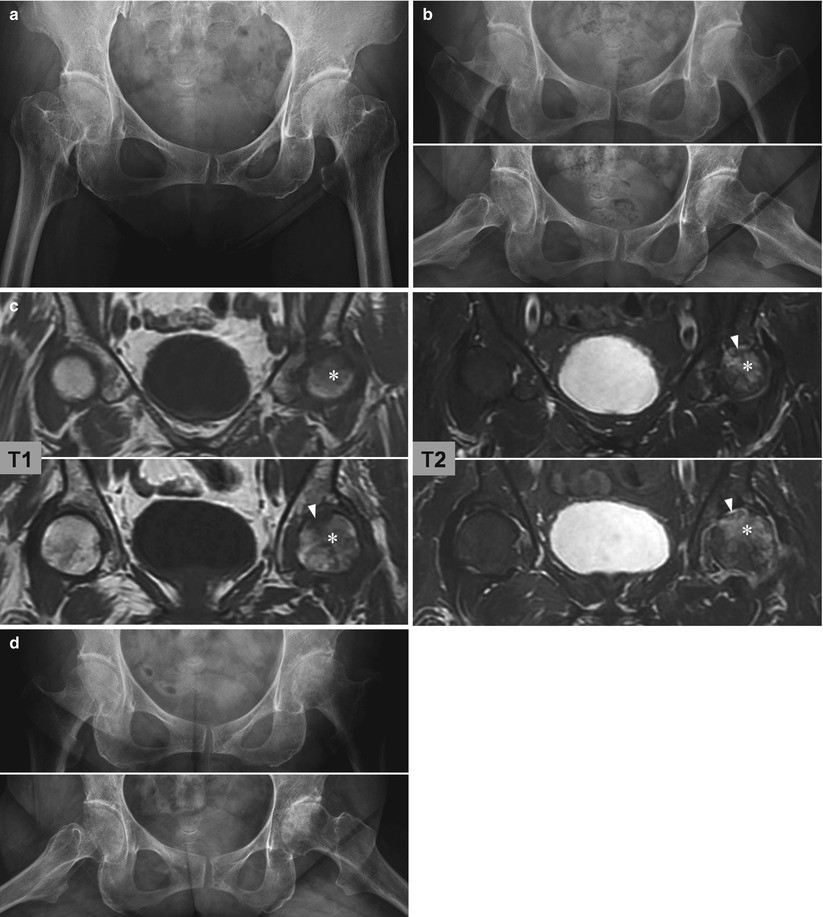

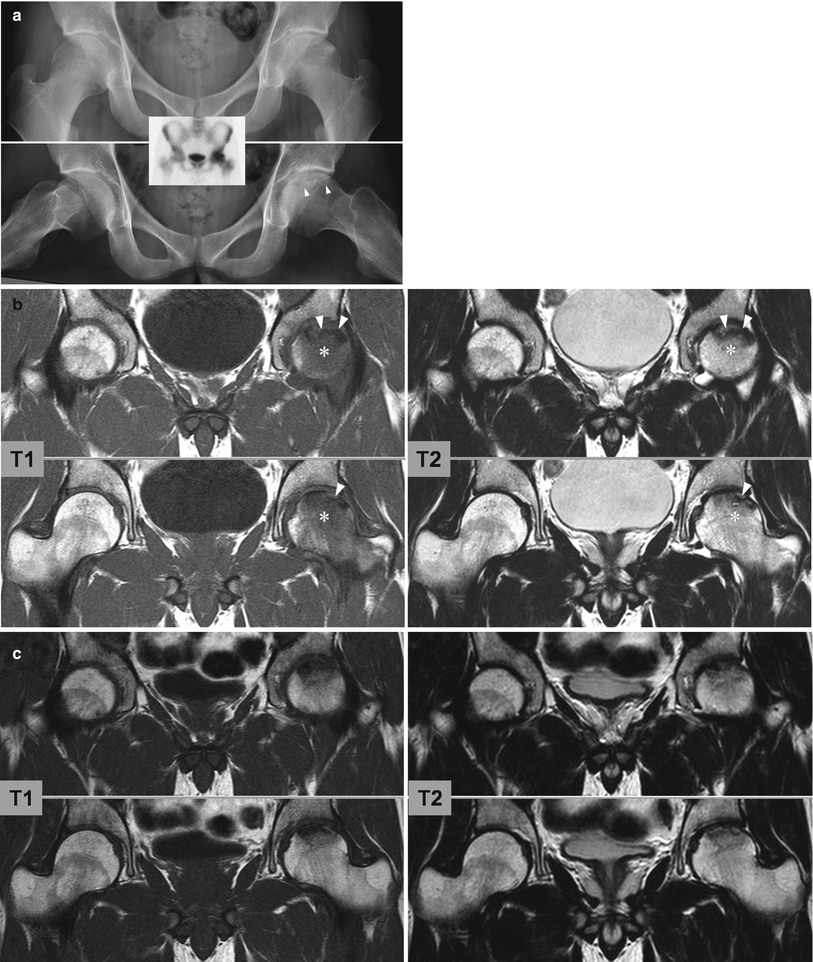

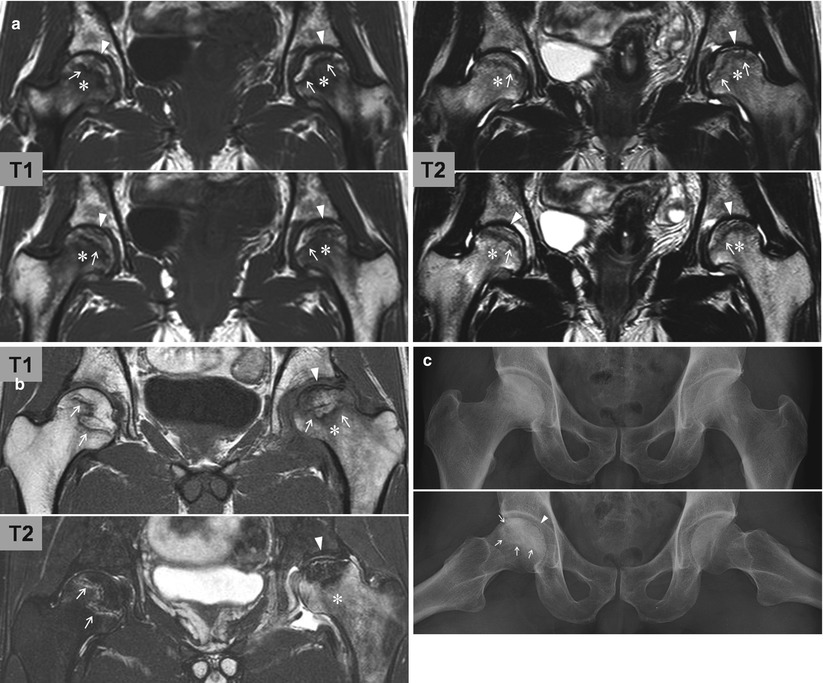

Immediately after the onset of pain, usually no remarkable abnormal findings are detected unless collapse of the femoral head has already occurred. With time, osteopenia in the proximal femur and/or subchondral fracture line can be detected together with femoral head collapse when it occurs, but not always (Figs. 29.1, 29.3, 29.4 and 29.6c). In insufficiency-type fractures of the elderly, joint space narrowing is frequently observed, but the mechanism is not known (Fig. 29.2). The subchondral fracture line is usually more apparent on frog-leg view as in ONFH (Figs. 29.3, 29.5c and 29.6c).

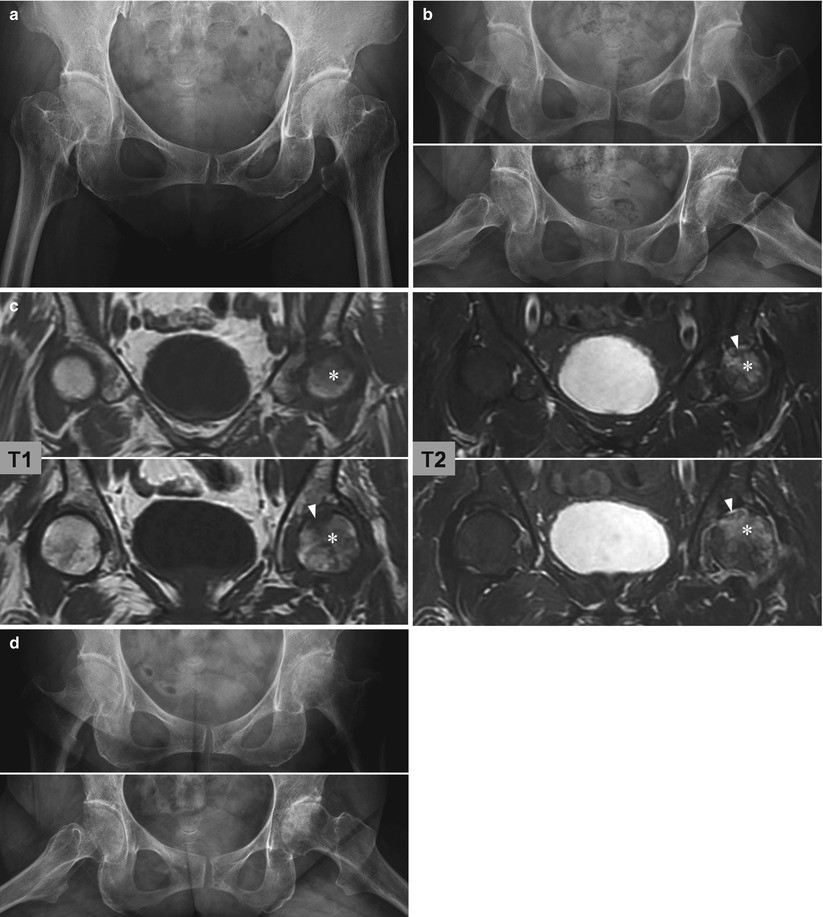

Fig. 29.2

A 65-year-old woman with insufficiency-type subchondral stress fracture of the femoral head. (a) Plain radiograph taken 2 months before the onset of left hip pain shows no remarkable abnormalities. (b) Radiographs taken 2 months after the onset of the left hip pain show joint space narrowing of the left hip without any other bony abnormality. (c) MR images of the hip show a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads) and bone marrow edema pattern (asterisks) extending to the subchondral area. (d) Radiographs taken 8 months later show slight progress of the joint space narrowing. Pain persists with some improvement

Fig. 29.3

A 20-year-old man with fatigue-type subchondral stress fracture of the femoral head.(a) Plain radiographs taken 1 month after the onset of the left hip pain show mild flattening of the left femoral head and a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads). Bone scintigraphy shows increased uptake in the left femoral head (inset). (b) MR images taken 1 month after the onset of the left hip show a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads) and bone marrow edema pattern (asterisks) extending to the subchondral area. (c) MR images taken 6 months later show marked decrease in the area of bone marrow edema pattern. (d) Radiographs taken 1.5 years after the onset of left hip pain show no further flattening of the femoral head

Bone scintigraphy always shows focal or diffuse increased uptake in the femoral head (Fig. 29.3). It is nonspecific for the diagnosis but valuable as a screening test.

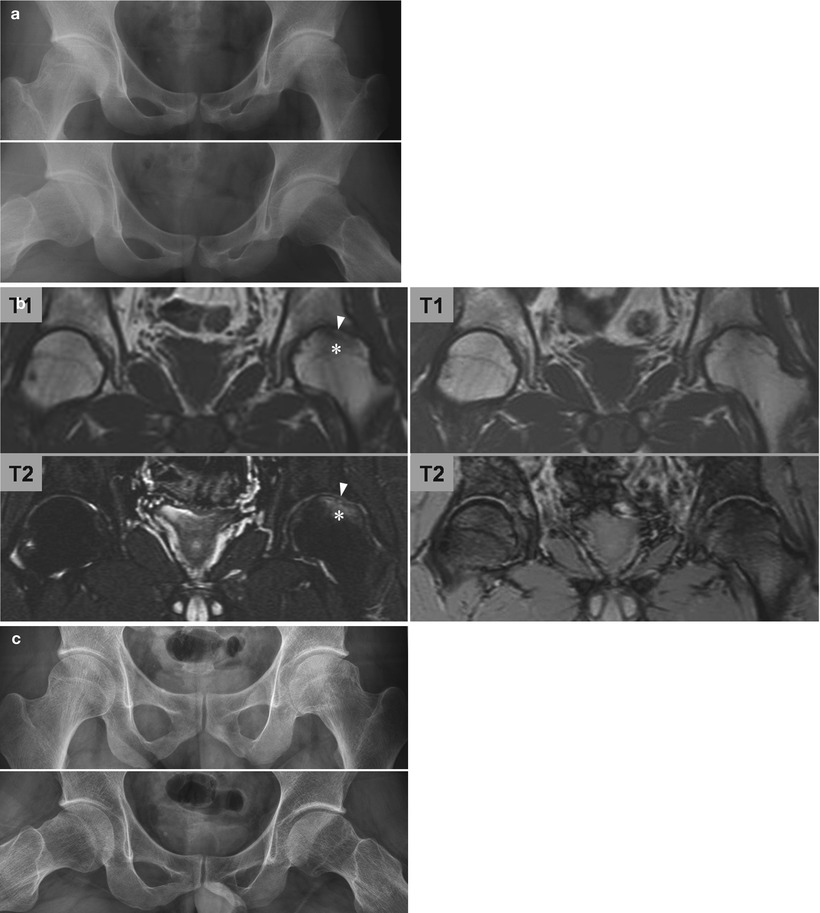

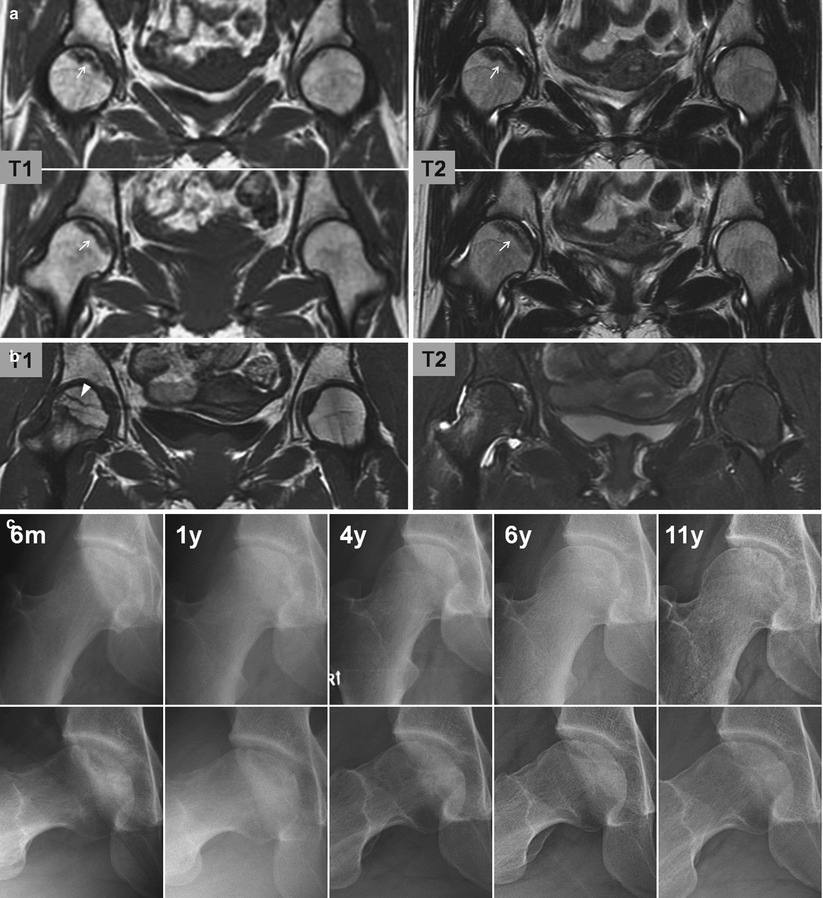

MR imaging is the most valuable and indispensible diagnostic tool (Figs. 29.1, 29.2, 29.3 and 29.4). Characteristic findings are subchondral abnormal intensity band and surrounding bone marrow edema pattern. The subchondral abnormal signal intensity band representing the fracture line is an essential finding for diagnosis. This irregular linear band is low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and variable abnormal signal intensity on T2-weighted images. The area of bone marrow edema pattern can be localized to the fracture line or diffuse in the femoral head and sometime extends to the intertrochanteric area. Bone marrow edema pattern decreases gradually and disappears completely together with the symptoms as the fracture heals. The collapse of the femoral head or thinning of the articular cartilage is identifiable when existing, and joint effusion is a frequent finding.

Fig. 29.4

A 20-year-old man with fatigue-type subchondral stress fracture of the femoral head. (a) Plain radiographs taken 4 months after the onset of left hip pain show moderate collapse of the left femoral head. (b) MR images taken 6 months after the onset of the left hip (left column) show a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads) and bone marrow edema pattern (asterisks) extending to the subchondral area. MR images taken 5 months later (right column) show disappearance of the bone marrow edema pattern and subchondral fracture line. (c) Radiographs taken 10 years after the onset of left hip pain show flattened femoral head with mild degenerative change. Patient has no pain and no limitation in daily activities

29.4 Treatment

No or protected weight bearing is a basic initial treatment for SSFFH with no or mild collapse of the femoral head. The duration of limitation in weight bearing has not been established.

The management for the collapsed femoral head is also not clear. When detected early, it is possible to elevate the collapsed area and maintain it until fracture healing by impaction of strut bone graft (Fig. 29.1); a few reports have described this approach [8, 29]. Recently, Yamamoto et al. reported successful short-term results of transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy for collapsed cases [44].

When symptoms persist with or without improvement with conservative treatment, usually in insufficiency-type fractures, THA is necessary.

29.5 Prognosis

Symptoms decrease gradually and disappear completely within several months. Symptoms tend to persist longer in collapsed cases, up to 9 months. When the fracture heals without collapse of the femoral head, no subsequent problems arise. In fatigue-type fractures, cases healed with moderate-to-severe collapse have been reported to do well without any significant symptom for more than 10 years (Fig. 29.4) [50].

Unlike fatigue-type fractures, conservative treatment is not successful in the large proportion of insufficiency-type fractures. Almost half of the reported cases received total hip arthroplasty because of inadequate improvement with conservative treatment [32, 45, 52]. The reason for this poorer result than fatigue-type fracture is not clear, but old age and joint space narrowing have been suggested to be associated with the poor result. Development of rapidly destructive coxopathy subsequent to insufficiency-type fractures has been reported [53–55].

29.6 Differential Diagnosis

As was pointed out in the first report of insufficiency-type SSFFH, the differentiation of ONFH and TOH from SSFFH is both necessary and important. ONFH has similar clinical and image findings, but the prognosis is very different from that of SSFFH; after the onset of pain, collapse of the femoral head and subsequent joint destruction progresses, and most cases need total hip arthroplasty.

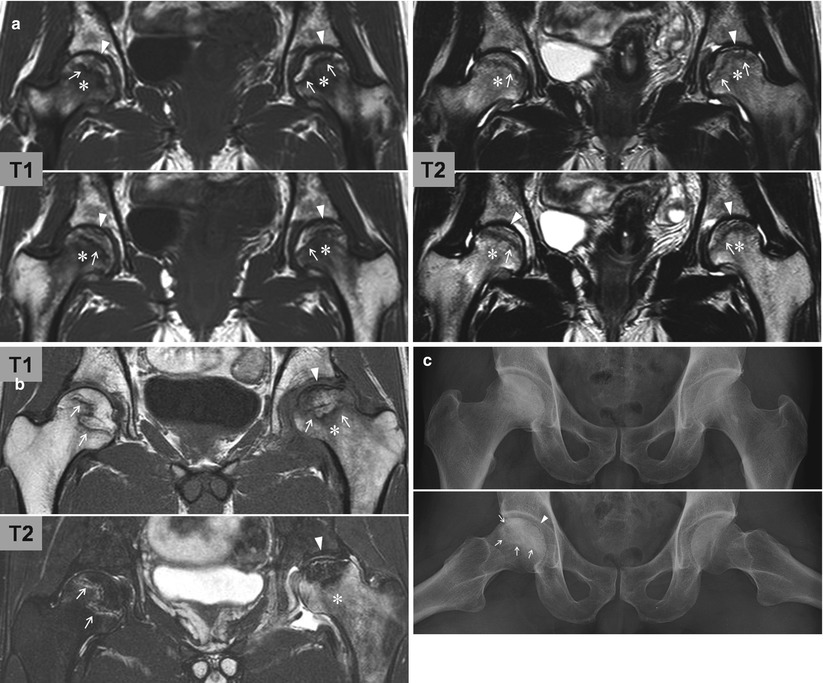

Subchondral fracture and bone marrow edema also occur in ONFH. However ONFH differs in two aspects (Fig. 29.5). In ONFH, an additional abnormal signal intensity band is detected outside the subchondral fracture line. The outer abnormal signal intensity band is the outer margin of the necrotic lesion, the reactive interface between dead and living bones [56, 57]. The reactive interface is apparent as a low signal intensity band on T1-weighted images and the band is the first detectable abnormal MR finding of ONFH [58–60]. In the early stage of ONFH, the reactive interface appears as an inner high and outer low signal intensity band, the so-called double line sign, on T2-weighted images. The other point of difference is the extent of the bone marrow edema [8, 29, 43, 61]. In ONFH, bone marrow edema occurs only outside the reactive interface and not in the necrotic area. On the contrary, bone marrow edema extends up to or over the subchondral fracture line in SSFFH. The convexity of the subchondral fracture line was proposed as a differential point because subchondral fracture lines are usually convex to the articular surface, and reactive interface lines are usually concave to the articular surface [62, 63]. However, both the concave subchondral facture lines and the convex reactive interfaces are detected occasionally (Figs. 29.5a and 29.6) [64]. Osteonecrotic lesions without subchondral fracture are always painless, and two bands of subchondral fracture and reactive interface are usually observed in symptomatic ONFH. When the reactive interface is detected clearly as a sclerotic line on plain radiographs, a differential diagnosis can be made without MR images (Fig. 29.5c).

Fig. 29.5

Image findings of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. (a) A 31-year-old woman had both left and right hip pain for 1 month. In addition to a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads), an outer abnormal signal band (reactive interface, arrows) is detected on MR images. The bone marrow edema pattern (asterisks) is located distal to the reactive interface. (b) A 28-year-old man had left hip pain for 6 months. There has been no pain in the right hip. In the left hip, a subchondral fracture line (arrow heads) is observed proximal to the reactive interface band (arrows) and bone marrow edema pattern (asterisks) is found distal to the band. In the right hip, only the reactive interface (arrows) is observed. Neither a subchondral fracture line nor a bone marrow edema pattern is detected. (c) A 53-year-old man had right hip pain for 3 years. Plain radiographs show sclerotic margin (reactive interface, arrows) of the necrotic lesion and a subchondral fracture line (arrow head) in the right femoral head

Fig. 29.6

Various convexity of the subchondral fracture line and the reactive interface. (a) MR images of a 17-year-old woman who had a history of steroid therapy for Hodgkin’s disease show an asymptomatic osteonecrosis in the right femoral head. The abnormal signal intensity band (arrows) in the right femoral head is the outer margin of the necrotic lesion, the reactive interface. The band is convex to the articular surface. There is neither a subchondral fracture line nor a bone marrow edema pattern. (b) MR images of a 28-year-old woman with hypophosphatemic rickets show subchondral fracture findings in both femoral heads. The fracture line (arrow heads) in the right femoral head is concave to the articular surface. (c) Serial radiographs of a 21-year-old man show healing of a fatigue-type subchondral fracture of the femoral head. The fracture fragment is large and the fracture line is concave to the articular surface

The clinical course and image findings of TOH, a condition of unknown etiology, are identical to those of SSFFH without femoral head collapse [25–31]. The only difference is that the subchondral fracture line is not detected in TOH. Miyanish et al. [28] detected suggestive findings of subchondral fracture in a retrospective review of MR images of cases previously diagnosed as TOH; subchondral fracture line was recognized in the MR images of many past publications of transient osteoporosis of the hip [65–76]. The differential diagnosis depends solely on the detection of the subchondral fracture line, but sometimes the fracture line can be detected only on some slices of MR images made with various techniques including gadolinium enhancement. In addition, it is likely to be more difficult or even impossible to detect the fracture line when it is incomplete. Recently, Kim et al. reported a case of bilateral TOH in which serial MPR CT findings suggested callus formation in the subchondral trabeculae followed by remodeling [31]. These propose that subchondral trabecular injury is likely the etiology of TOH.

29.7 Summary

SSFFH and ONFH are similar but definitely different diseases. The prognosis of SSFFH is much better than that of ONFH. Therefore, it is extremely important to make a differential diagnosis and it is possible with MR images. TOH may well be the milder form of subchondral trabecular bone injury.

References

1.

2.

Motomura G, Yamamoto T, Miyanishi K, Shirasawa K, Noguchi Y, Iwamoto Y. Subchondral insufficiency fracture of the femoral head and acetabulum: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(6):1205–9.PubMed

3.

4.

5.

Pateder DB, Park HB, Chronopoulos E, Fayad LM, McFarland EG. Humeral head osteonecrosis after anterior shoulder stabilization in an adolescent: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(10):2290–3.PubMed

6.

Yamamoto T, Schneider R, Iwamoto Y, Bullough PG. Rapid acetabular osteolysis secondary to subchondral insufficiency fracture. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):592–5.PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree