and Michael F. Sorrell2

(1)

Herbert B. Saichek Professor of Radiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

(2)

Robert L. Grissom Professor of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

135 Arterioportal Shunt I: Early Enhancing Lesion in a Cirrhotic Liver

Cirrhotic livers may contain various types of enhancing lesions and pseudolesions. In clinical practice with cirrhotic patients, however, we have sometimes encountered small nodular early enhancing hepatic lesions on arterial phase contrast-enhanced dynamic CT or MRI that resembled hepatocellular carcinomas but disappeared or decreased in size during the clinical follow-up examinations. These lesions are considered to be nonneoplastic hypervascular pseudolesions caused by small arterioportal or other shunts including unknown causes and are often difficult to differentiate from hypervascular hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs). Some reports indicate that single-level dynamic CT during hepatic arteriography and less invasive contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI with higher temporal resolution from early to late arterial phase may be helpful for differentiating the early enhancing lesions from HCC.

MR Imaging Findings

At MR imaging, the early enhancing lesions are typically small (a few millimeters) and visible in the arterial phase of the dynamic gadolinium-enhanced imaging, fading to isointensity in the delayed phase in most cases. On the maximum-intensity projection images, an enhanced arterial vessel may be seen coursing toward the area of an arterioportal shunt (Figs. 135.1, 135.2, and 135.3a, b). Although delayed persistent enhancement has been described in the literature, any heterogeneity and signal abnormality on T2-weighted images as well as chemical shift imaging should be considered suspicious and warrant follow-up (Fig. 135.3c, d).

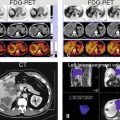

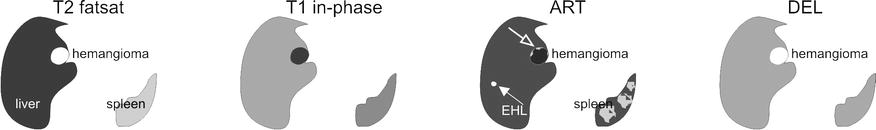

Fig. 135.1

Early enhancing lesion (EHL) in a cirrhotic liver, drawings. T1 opposed phase: the liver shows morphologic signs of cirrhosis with enlarged spleen. T1 opposed phase: (lower anatomic level) the liver shows signs of cirrhosis. ART: at least two EHLs (arrow) are visible. ART: another EHL is visible at a lower anatomic level (arrow). [Follow-up MRI did not show any change or other signs of malignancy]

Fig. 135.2

Early enhancing lesion (EHL) in a cirrhotic liver, MRI findings. (a) Axial opposed-phase image (T1 opposed phase): the liver shows several nodules and morphology of cirrhosis. (b) Axial opposed-phase image (T1 opposed phase) at a lower anatomic level: the liver contains several nodules with variable signal intensity (arrows). (c) Axial arterial phase image (ART) shows the intensely enhancing EHLs (arrow). (d) Axial arterial phase image (ART) at a lower anatomic level shows another EHL (arrow). (e–h) Maximum-intensity projections (MIP) based on the subtractions of the arterioportal phases show several EHLs (arrows) with suggestion of arterioportal shunts. [Follow-up MR imaging during several months did not show any change or signs of malignancy]

Fig. 135.3

EHLs in a cirrhotic liver, drawings (a, b); (c, d) show dysplastic nodule in another patient. (a, b) Drawings show the connection between the arteries and portal veins, suggesting arterioportal shunts. (c) Axial arterial phase (ART) and (d) TSE (T2 fatsat) images show an enhancing area (arrow) that is faintly hyperintense to the liver on the T2-weighted image (arrow). At follow-up MRI, this area developed into an HCC

Differential Diagnosis

Dysplastic nodules and small HCC may be distinguished from arterioportal shunt and pseudolesions (i.e., areas with nonspecific transient increased enhancement) based on the appearance on the delayed phase as well as findings on other sequences. In ambiguous cases, follow-up MR imaging may facilitate distinction.

Literature

1. Ito K, Fujita T, Shimizu A, et al. Multiarterial phase dynamic MRI of small early enhancing hepatic lesions in cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis: differentiating between hypervascular hepatocellular carcinomas and pseudolesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:699–705.

2. Yu JS, Kim KW, Jeong MG, Lee JT, Yoo HS. Nontumorous hepatic arterial-portal venous shunts: MR imaging findings. Radiology. 2000;217:750–6.

3. Ueda K, Matsui O, Kawamori Y, et al. Differentiation of hypervascular hepatic pseudolesions from hepatocellular carcinoma: value of single level dynamic CT during hepatic arteriography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:703–8.

136 Arterioportal Shunt II: Early Enhancing Lesion in a Non-cirrhotic Liver

According to some authors, arterioportal (AP) shunt is commonly associated with hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. However, congenital or acquired AP shunt without any associated hepatic tumor may occur and cause difficulty in diagnosis on ultrasound and computed tomography (CT). Particularly, on CT images the enhancing area of the liver may mimic a lesion. State-of-the-art MR imaging of the liver combines the information concerning the vascularity and soft tissue characteristics of the lesions and can make a more confident diagnosis.

MR Imaging Findings

At MR imaging, AP shunt is not visible on the T2-weighted and in-phase T1-weighted images. In a fatty liver, however, the area with the shunt may show fatty sparing on the opposed-phase images. After injection of gadolinium, the shunt may be visible as a small intensely enhancing lesion in the arterial phase, followed by a wedge-shaped enhancement of the surrounding parenchyma. In the delayed phase, the enhancing lesion and area fade to isointensity. In addition, other concurrent benign liver lesions may be seen (Figs. 136.1, 136.2, and 136.3).

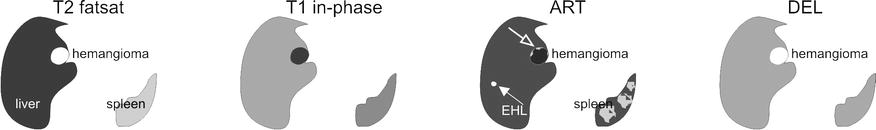

Fig. 136.1

Early enhancing lesion (EHL) and a hemangioma, drawings. T2 fatsat: at the site of EHL, no abnormality is visible; note an incidental bright hemangioma. T1 in-phase: the liver shows normal signal intensity. ART: EHL (arrow) is visible with faint peripheral nodular enhancement of hemangioma (open arrow). DEL: EHL is no longer visible; hemangioma shows homogeneous enhancement

Fig. 136.2

Early enhancing lesion (EHL) and a hemangioma, MRI findings. (a) Axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted TSE image (T2 fatsat): the liver parenchyma is normal at the site of EHL. Hemangioma is hyperintense to the liver. (b) Axial in-phase GRE (T1 in phase): the liver shows normal signal. (c) Axial early arterial phase image (ART) shows the intensely enhancing EHL (arrow) and faint peripheral nodular enhancement within hemangioma (open arrow); note that the portal vein has not yet enhanced (*). (d) Axial delayed phase image (DEL): EHL has disappeared and hemangioma shows homogeneous enhancement (open arrow). (e) Axial SSTSE image (SSTSE): hemangioma remains bright. (f) Axial opposed-phase image (T1 opposed phase): fatty infiltration (*) is present except around the area of the EHL. (g) Axial late arterial phase image (ART), with enhanced portal vein (*), shows wedge-shaped enhancement of the liver surrounding EHL. (h) MIP based on the subtractions of the early and late arterial phases strongly suggests an arterioportal shunt (arrows)

Fig. 136.3

EHL caused by arterioportal shunt and hemangioma, drawings. (a) Before contrast normal liver with a hemangioma is visible. (b) Arterial phase shows the EHL surrounded by an enhancing wedge-shaped area. (c) Delayed phase shows the enhanced hemangioma. (d) A composite drawing based on the subtraction images shows the connection between the arteries and portal veins, the most likely cause of the EHL (AP shunt)

Differential Diagnosis

Any underlying or associated liver tumor such as cholangiocarcinomas or HCCs can be distinguished on MR imaging based on the tissue characteristics and enhancement patterns.

Literature

1. Routh WD, Keller FS, Cain WS, et al. Transcatheter embolization of a high-flow congenital intrahepatic arterial-portal venous malformation in an infant. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:511–4.

2. Kitade M, Yoshiji H, Yarnao J, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with central calcification and arterio-portal shunt. Intern Med. 2005;44:825–8.

137 Budd-Chiari Syndrome I: Abnormal Enhancement and Intrahepatic Collaterals

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare and potentially lethal condition related to the obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract. Women of about 35 years are the most affected group. Heart failure and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (formerly known as venoocclusive disease) also impair hepatic venous outflow and share many features with BCS, but these are separate entities as causes and treatments differ. Thrombosis is the cause of primary BCS. As compared with pure hepatic vein thrombosis, IVC thrombosis is more common in the Far East; it is more indolent and is complicated more commonly by hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, the recently proposed distinction of primary hepatic vein thrombosis (true BCS) from primary IVC thrombosis (obliterative hepatocavopathy) is well suited for clinical and therapeutic objectives. However, etiologies are similar. In most studies, primary myeloproliferative disorders are found to be the leading cause of BCS. The blood outflow obstruction of the liver may result in liver congestion, portal hypertension, ischemic necrosis caused by sudden interruption of hepatic perfusion followed by fibrosis and liver failure, and ascites. Imaging evaluation of patients with suspected BCS may be critical, since the clinical presentation of this potentially fatal disease is often nonspecific. The overall accuracy of US and CT for detecting hepatic venous thrombosis has been reported as approximately 70 and 50 %, respectively.

MR Imaging Findings

Diagnostic percutaneous venography (may show spider web network pattern formed by the intrahepatic collaterals with incomplete occlusion of the hepatic veins) is invasive and obsolete in the era of the state-of-the-art MR imaging. The diagnosis of primary BCS can be established when an obstructed hepatic outflow tract is shown in the absence of tumoral invasion or compression. MR imaging can show the parenchymal changes, the enhancement patterns in the arterial and delayed phases, and the intrahepatic collaterals and can exclude any tumors with high level of confidence (Figs. 137.1 and 137.2). Ultrasound is an excellent modality for the evaluation of blood flow within hepatic vessels as well as after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) but does not provide an overview of the (vascular) anatomy (Fig. 137.3).

Fig. 137.1

Budd-Chiari syndrome, drawings. T2 fatsat: the liver shows peripheral atrophy (p) with high signal and central hypertrophy (*) with normal low signal; (IVC = inferior vena cava ). T1 in phase: note almost normal high signal centrally (*). ART: intrahepatic abnormal arteries (intrahepatic collaterals) are visible (arrows). DEL: intrahepatic abnormal veins (intrahepatic collaterals) are visible (arrows). Note peripheral increased enhancement

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree