Case presentation

A 4-month-old male presents with bilateral scrotal swelling. Per the mother, this has been present since 1 month of age but has worsened over the past week and she has noted that the right side of the scrotum appears darker than normal. The mother also states that there has been mild congestion and cough for the past week and today the child developed a fever to 102.5 degrees Fahrenheit. There have been no other symptoms, including vomiting, diarrhea, rash, or fussiness. He has been drinking well. His physical examination reveals a temperature of 101 degrees Fahrenheit, a respiratory rate of 30 breaths per minute, and a heart rate of 120 beats per minute. He is very well appearing and in no distress. He has mild nasal congestion with normal tympanic membranes. His lungs are clear. His abdominal examination is unremarkable; there is no apparent tenderness, masses, or hepatosplenomegaly. His genital examination shows an uncircumcised male with the scrotum markedly enlarged bilaterally making the examination difficult. There is no erythema; there are no palpable masses; there is induration but no palpable fluctuance. Transillumination of the scrotum reveals probable fluid.

Imaging considerations

Pediatric scrotal complaints can be acute or chronic, involving the testicle or extratesticular structures. Common etiologies of acute scrotal pain or swelling include traumatic (i.e., scrotal hematoma or testicular rupture), infectious (epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis, cellulitis), and vascular (testicular torsion or torsion of an appendix testis) causes. Included in this acute group is scrotal wall edema, which may be due to insect bites/stings or be associated with Henloch-Schönlein purpura, often as a first sign of this disease process. , Another finding that may be seen in pediatric patients is testicular microlithiasis. These arise from calcifications in the seminiferous tubules, and their clinical significance is not entirely certain. While often idiopathic, microlithiasis can be associated with certain congenital syndromes, such as Down syndrome and Kleinfelter syndrome. They were once considered to place patients at risk for testicular cancer, but this association has been questioned, especially in asymptomatic patients. While no standardized protocols exist for cancer surveillance risk, the finding of scrotal microlithiasis should prompt referral to Pediatric Urology for ongoing surveillance.

Chronic scrotal complaints in the pediatric population are usually congenital and include hydroceles and undescended testes. Undescended testes, termed cryptorchidism, are an important finding. The testes may be located anywhere along the path where testicles descend, but the inguinal canal is the most common location; they appear as asymmetric, small, and hypoechoic compared to normal testis. Finding undescended testes should prompt referral to Pediatric Urology, as they do pose a risk for testicular cancer. , , ,

Neonatal scrotal swelling is most often due to congenital hydrocele, but other etiologies, such as inguinal hernias (more commonly seen in premature infants ), scrotal hematomas (associated with high birth weight, trauma, and bleeding diasthasis ), neoplasm (rare—either germ cell tumors or stromal tumors), and testicular torsion (occurs most often in utero ) have all been reported.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality to evaluate acute and chronic scrotal complaints in the pediatric population. The excellent resolution, lack of ionizing radiation, and Doppler capabilities make this modality an ideal imaging choice to identify important anatomical landmarks, such as the epididymis, spermatic cord, and testes, as well as visualizing the inguinal canal. Doppler imaging is excellent for visualizing blood flow to the testis and surrounding structures. , Expertise in the performance and interpretation of pediatric scrotal ultrasound is required for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Imaging findings

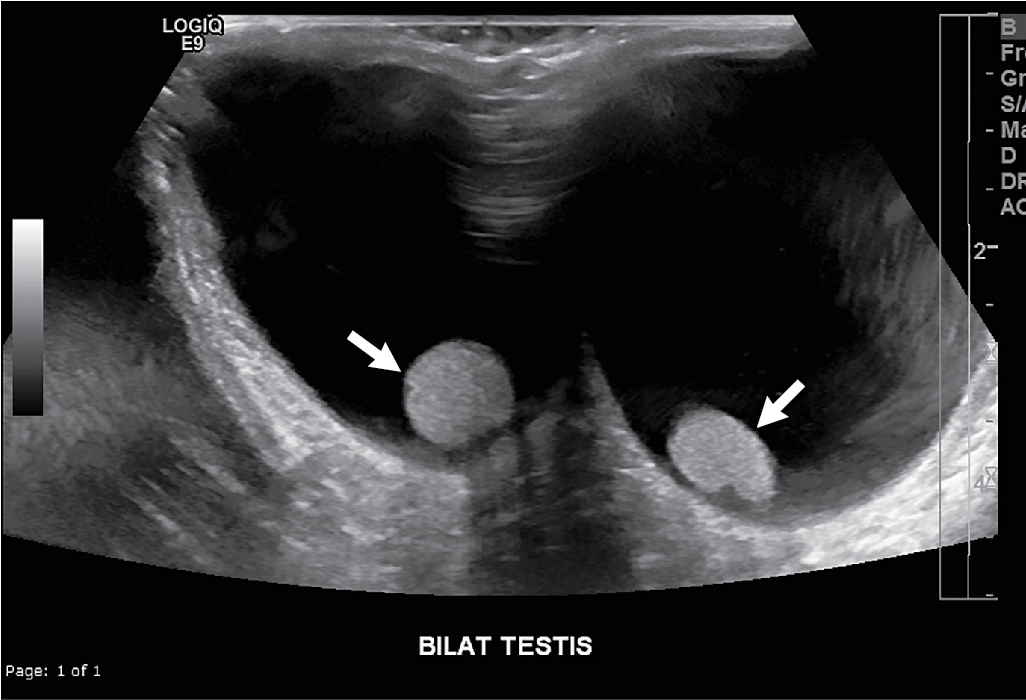

The child had ultrasonography with color-flow duplex Doppler performed of the testes and scrotal contents. Selected images are provided. There are bilateral, large, simple hydroceles ( Fig. 22.1 ); the testes are normal in echotexture and location. Duplex Doppler demonstrates normal waveforms with normal amplitude, indicating normal blood flow to the testes ( Figs. 22.2 and 22.3 ). There is no evidence of testicular torsion.