5 The abdomen

Anterior abdominal wall

Muscle layers

The rectus abdominis muscle is a thick ribbon of muscle on either side of the midline from the costal cartilages to the pubic crest. It has three to four tendinous intersections at intervals along its length, which adhere to the anterior rectus sheath (Fig. 6.13B). The rectus sheath is formed by the aponeuroses of the other abdominal wall muscles as they surround the rectus muscle to attach to the linea alba.

Radiological features of the anterior abdominal wall

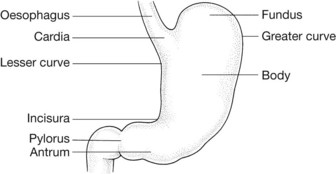

The stomach (Figs 5.5–5.9)

Anterior relations of the stomach

The upper part of the stomach is covered by the left lobe of the liver on its right and by the left diaphragm on the left (Fig. 5.46A). The fundus occupies the concavity of the left dome of the diaphragm. The remainder of the anterior of the stomach is covered by the anterior abdominal wall.

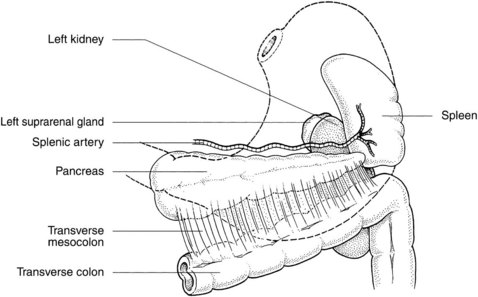

Posterior relations of the stomach (Fig. 5.6)

Posterior to the stomach lies the lesser sac (see section on peritoneal spaces of the abdomen later in the chapter, and Figs 5.52 and 5.53). The structures of the posterior abdominal wall that are posterior to this are referred to as the stomach bed. The pancreas lies across the midportion of the stomach bed with the splenic artery partly above and partly behind it, and the spleen at its tail. Above the pancreas are the aorta and its coeliac trunk and surrounding plexus and nodes, the diaphragm, the left kidney and the adrenal gland. Attached to the anterior surface of the pancreas is the transverse mesocolon, which forms the inferior part of the stomach bed.

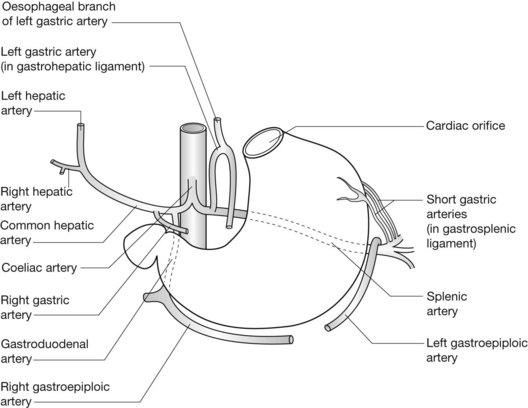

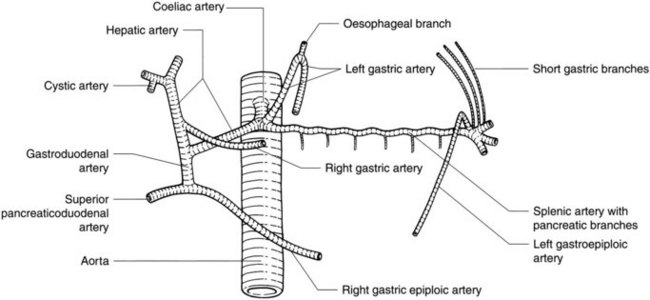

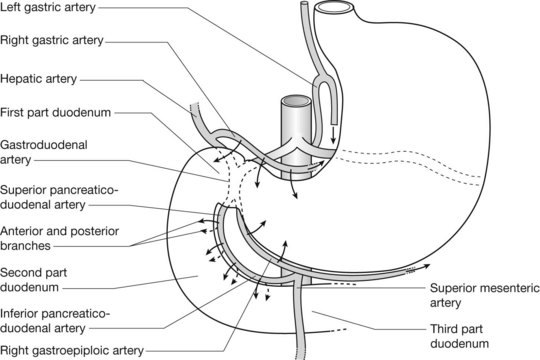

Arterial supply of the stomach (Fig. 5.7; see also Figs 5.12, 5.13)

The left gastric artery also supplies branches to the lower oesophagus.

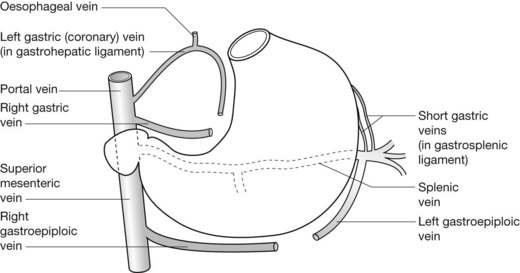

The venous drainage of the stomach (Fig. 5.8)

The venous drainage of the stomach follows a similar pattern to the arterial supply:

Lymph drainage of the stomach

Lymph drainage also follows the arterial pattern and drains to nodes around the coeliac trunk:

Radiological features of the stomach

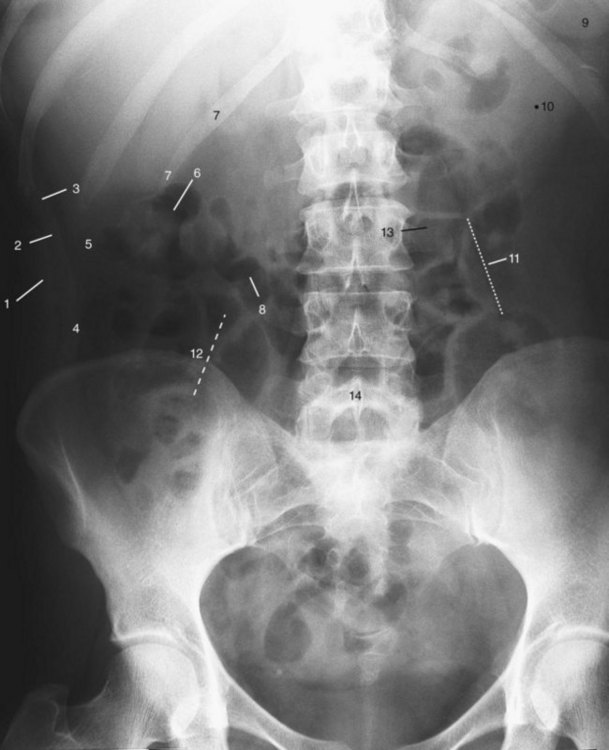

Plain film of the abdomen (see Fig. 5.1)

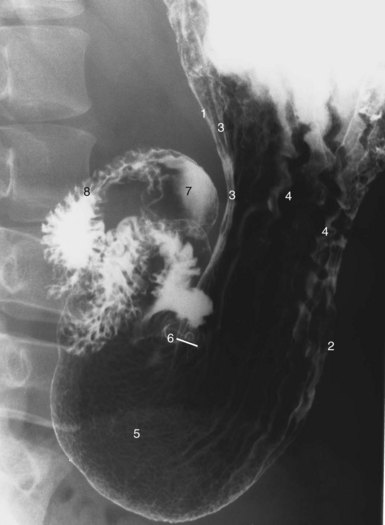

Double-contrast barium-meal examination (Fig. 5.9)

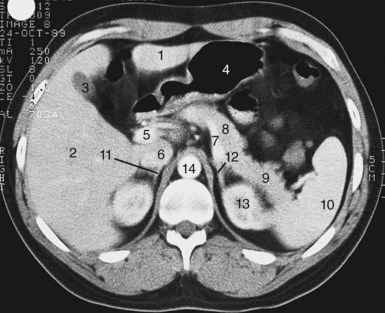

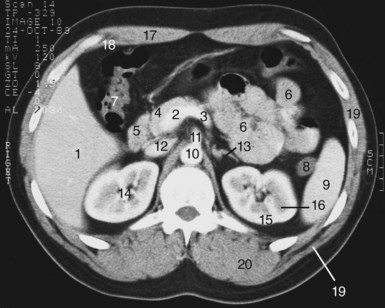

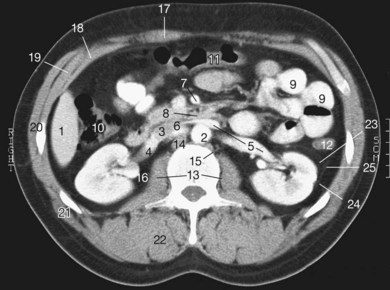

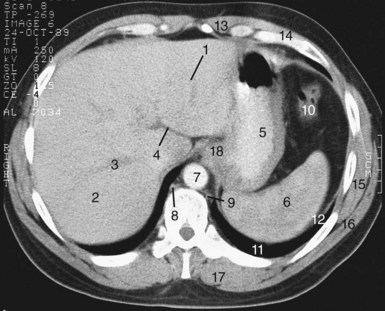

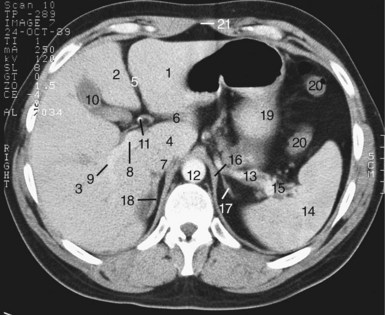

CT and MRI of the stomach

The relationship of the stomach to the structures of the stomach bed, such as the pancreas, the aorta, the spleen and the left kidney and adrenal, can be seen (Figs 5.10 and 5.11; see also Fig. 5.2).

Ultrasound studies of the abdomen

These are limited by the presence of intraluminal gas in the stomach and bowel. Structures in the stomach bed cannot be seen through the stomach if this is filled with gas. If the stomach is gas free or fluid filled, then the pancreas and the aorta and coeliac trunk can be well seen. The antrum and gastro-oesophageal junction can normally be identified by their characteristic hypoechoic muscular layer surrounding echogenic mucosa. The gastro-oesophageal junction is seen as a small rounded structure behind the top of the left lobe of the liver (see Fig. 5.29B). The antrum is more elongated and is seen behind the left lobe of the liver, just to the right of the midline.

The duodenum (Figs 5.14, 5.15)

Radiological features of the duodenum

Barium studies of the duodenum (Figs 5.9, 5.15)

The duodenum is usually examined radiologically as part of a double-contrast barium-meal examination (see Fig. 5.9).

Radiology pearls

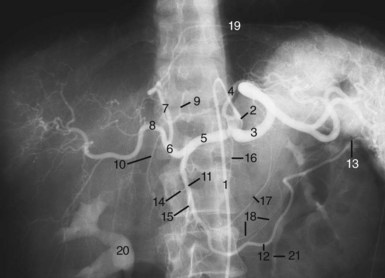

Angiography

For full angiographic assessment of the duodenum, both the coeliac trunk and the superior mesenteric arteries must be visualized (Fig. 5.12; see also Fig. 5.20).