© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014

Ralf Puls and Norbert Hosten (eds.)Whole-body MRI Screening10.1007/978-3-642-55201-4_11. The Ethics of Incidental Findings in Population-Based MRI Research

(1)

Department of Philosophy, Universität of Hamburg, Von-Melle-Park 6, Hamburg, 20146, Germany

(2)

Department of Philosophy, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Domplatz 6, Münster, 48143, Germany

1.1 Introduction

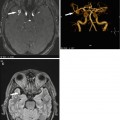

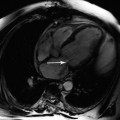

The occurrence of incidental findings in epidemiologic studies is a well-recognized problem in medical research methodology. Radiologists and epidemiologists have discussed incidental findings in terms of empirical frequency and methodological implications for some time, and there has been an upsurge of interest in this topic over the last few years. In large measure, this growing interest has been fueled by an increase in incidental findings, which is attributable to the fact that state-of-the-art imaging modalities have become established research tools and are now widely used in population-based studies. It is estimated that 1–8 % of human subjects participating in research involving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain have clinically relevant findings (Katzman et al. 1999; Alphs et al. 2006; Vernooij et al. 2007; Gupta and Belay 2008). Still, the brain appears to be among the organs that generate relatively few incidental findings. Recent data suggest that incidental findings are much more common when other organs are examined. Brudermanns (2008), for instance, reported a rate of 41 % in cardiac multidetector computed tomography (CT) studies. Valid estimates on the frequency of incidental findings in whole-body MRI studies are still lacking, probably because, up to now, this complex imaging modality has very rarely been used on a large scale for research purposes. The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is one of the first population-based studies using whole-body MRI in a large sample of normal volunteers.

With more incidental findings being encountered in imaging research, it has become apparent that dealing with them not only affects research methodology but also raises fundamental ethical issues. A survey of the literature reveals that researchers first began discussing the ethics of incidental findings in greater depth around 2005, highlighting the need for a systematic ethical analysis that would offer investigators guidance in handling incidental findings detected with modern imaging technology in the context of epidemiologic research. The SHIP investigators set up an Advisory Board to address the problem of incidental findings, to decide which findings to disclose and, where necessary, to make decisions on an individual basis (for more details, see Chap. 2).

In this chapter, we take a broader perspective, going beyond the specific problems of incidental findings encountered in the SHIP, and seek instead to identify the core of the ethical problems posed by incidental findings in general. We have chosen to do so because there is currently no general consensus on what constitutes the core of the ethical problems and how these problems are related to each other. An accurate description of the core problem is indispensable for arriving at a solution that is sound in both theory and practice.

Following a brief discussion of the meaning of “incidental findings” (Sect. 1.2), we will work out the core of the ethical dilemma, based on what medical research ethics discussions have focused on so far. We will then go on to outline some of the ethical issues arising indirectly from incidental findings (Sect. 1.3). We present our reasoning and explain why we believe it is crucial to identify the central ethical dilemma before we can suggest possible solutions and provide ethically adequate guidance in dealing with incidental findings. To conclude, we present a preliminary sketch of a possible solution to the central ethical dilemma underlying the problems researchers face in dealing with incidental findings (Sect. 1.4) and outline areas for further investigation.

1.2 What Are Incidental Findings?

While there is no generally accepted definition of what constitutes an incidental finding, in the literature it is usually characterized by three features. These features, which are largely undisputed, are included in the widely quoted definition proposed by Wolf et al. that an incidental finding is “a finding concerning an individual research participant that has potential health or reproductive importance and is discovered in the course of conducting research but is beyond the aims of the study” (Wolf et al. 2008, p 219). Restricting the occurrence of incidental findings to research subjects may at first glance appear too narrow. After all, there is also a risk of discovering incidental findings of potential relevance to an individual’s health in activities other than research (e.g., the acquisition of MR images for an anatomic atlas or in other examinations of healthy subjects). However, this restriction makes sense for our line of argument and also in conjunction with the third feature, namely, that an incidental finding is a finding that is beyond the aims of the study. Alternatively, some authors use the term “unexpected” to characterize incidental findings (Illes et al. 2006, p 783; Heinemann et al. 2007, p A1982). This characterization is misleading, though, since investigators are now generally aware of the significant potential for incidental findings when performing research using MRI. Characterizing these findings as unexpected only makes sense with regard to the individual subject but not when the study population as a whole is concerned. Quite the contrary appears to be true today: incidental findings are anticipated by researchers (Rangel 2010, p 124). Therefore, unexpectedness is not what distinguishes incidental findings from other findings. What is crucial, instead, is that incidental findings are not what the researcher is looking for, i.e., they are unintended. As will become clear as we proceed, the fact that incidental findings are not intended is central to the ethical issues they give rise to.

The crucial point regarding the second feature is that incidental findings are characterized as being of potential rather than actual health or reproductive importance. By definition, then, incidental findings also include findings that may be so marginal as to have no clinical significance. Moreover, they include false-positive findings, i.e., abnormalities that are found to be harmless upon further diagnostic evaluation (Woodward and Toms 2009).

Some authors characterize incidental findings as being detected in normal volunteers (Hoggard et al. 2009), but restricting the definition to normal volunteers is inadequate for two reasons. First, an incidental finding can relate to a hitherto undiagnosed condition in a person with a known disease (e.g., when a cancer patient taking part in a clinical study is diagnosed with multiple sclerosis). Second, a central feature of an incidental finding is precisely that a volunteer considered to be healthy at the time of enrollment in a study turns out to be (potentially) ill. Strictly speaking then we should say: incidental findings concern a disease of which the subject was unaware at the time of the study. In light of this more precise characterization of incidental findings, we refer to the persons in whom incidental findings can be detected as subjects or volunteers rather than patients.

1.3 Ethical Problems Posed by Incidental Findings in Epidemiologic Population-based Research

Although research ethics has become an established domain of medical ethics and medical law over the last two decades, there are relatively few publications on the ethics of incidental findings in epidemiologic studies. Caughlin and Beauchamp’s Ethics and Epidemiology from 1996 does not deal with this topic. The first publications addressing the ethical issues arising from incidental findings appeared at the beginning of this century (Illes et al. 2002, 2004). A wider debate of incidental findings ensued after the 2005 meeting on Detection and Disclosure of Incidental Findings in Neuroimaging Research in Bethesda (ML), which was organized by Stanford University and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). A brief summary of the results of this meeting was published in Science (Illes et al. 2006), triggering an intensified interest in the management of incidental findings by the research community.

A set of seminal articles appeared in the summer 2008 issue of the Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics (36:216–383). These articles were the result of a 2-year project on Managing Incidental Findings in Human Subjects Research, funded by the NIH and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). The project involved 21 scientists (Principal Investigator: Susan M. Wolf) and dealt with the ethical, legal, clinical, and scientific issues arising in the management of incidental findings. Although this set of articles represents a breakthrough in the debate, the authors treat the ethics of incidental findings as only one of several aspects.

In German-speaking countries, treatment of these ethical issues is limited to a few publications (Hentschel and Klix 2006; Heinemann et al. 2007, 2009b; Schleim et al. 2007; Fuchs et al. 2010, p 183–184; Langanke and Erdmann 2011; Schmücker 2013) and discussions in Deutsches Ärzteblatt (2007, 46:A3184–88) and Clinical Neuroradiology (Hentschel and von Kummer 2009; Heinemann et al. 2009a). A comprehensive legal framework governing the management of incidental findings is still lacking in both Germany and the USA (Code of Federal Regulations (United States Department of Health and Human Services 2005)) (see the overview of current recommendations given by Booth et al. 2010). Lately, however, researchers have been lamenting this situation and calling for guidelines to be developed (Brown and Hasso 2008; van der Lugt 2009). In Germany, the process of developing a guideline sparked a controversy (Hentschel and von Kummer 2009; Heinemann et al. 2009a). “Incidental findings” is not listed as an index term in current textbooks of bioethics (Gert et al. 2006; Beauchamp and Childress 2013) or reference works on applied and biomedical ethics (Frey and Wellman 2003).

Although many of the above-quoted authors discuss the legal, ethical, and practical issues surrounding the detection of incidental findings in great depth, we feel that they have not addressed the true core of the ethical problem.

We proceed by briefly summarizing the central concerns of research ethics (Sect. 1.3.1) and discussing them in relation to incidental findings. While these concerns may easily be interpreted to imply that incidental findings do not pose specific medical ethical problems, we will argue that scientists dealing with incidental findings are indeed confronted with a serious ethical conflict (Sect. 1.3.2).

1.3.1 Central Ethical Concerns in Human Subjects Research

Currently, the focus of medical research ethics is on three main topics: (a) clinical research in patients, (b) research involving vulnerable subjects (e.g., children, cognitively impaired persons, prisoners), and (c) the conduct of pharmaceutical trials in developing countries (see, e.g., Maio 2002). The reason that these are the central ethical concerns of medical research ethics is apparent from the serious conflicts, in terms of individual and social ethics, that these research practices generate:

(a)

Clinical research is typically conducted in patients, i.e., diseased persons who seek or require medical treatment. Thus, in the framework of a clinical study, both the doctor and the patient assume dual roles. The former is both physician and researcher, and the latter is both patient and research subject. As a patient, an individual has a right to the best medical care available, while as a study subject he or she may not receive the best treatment possible – when the study protocol assigns him or her to a control group treated with placebo, for example. Whether – and, if so, to what extent – it is ethically justifiable to deny subjects/patients therapeutic options that might be more effective than what they receive in the clinical trial is still under debate (Freedman 1987; Miller and Brody 2003, 2007; Veatch 2007; Hoffmann and Schöne-Seifert 2009).

(b)

Research involving vulnerable populations gives rise to an ethical conflict because vulnerable subjects are unable or limited in their ability to give informed consent (Fischer 2008). Nevertheless, such research is necessary, for example, to ensure that children receive the best possible treatment. The organism of a child is different in its physiologic and metabolic processes, and adult medications and dosages must be adjusted to be effective. Not doing research in children simply because they cannot give informed consent would render them therapeutic orphans, who would rely for treatment on drugs whose efficacy, safety, and dosage have only been proven in adults. The ethical problems are especially acute when children enrolled in pharmacologic trials do not themselves benefit from the research (Merkel 2003; Fleischman and Collogan 2008), but even research performed in the child’s best interest raises a number of ethical concerns (Hoffmann and Schöne-Seifert 2010).

(c)

Pharmacologic research in developing countries is attractive to profit-oriented companies, which sponsor most of these trials: it saves costs, and the laws governing human subjects research are usually less strict. However, these research practices violate the principle of justice in two respects. First, destitute persons in developing countries may be more willing to participate in research for little pay because of their threatening economic situation. Second, the results of research conducted in developing countries will mostly benefit patients in countries with better healthcare systems and not the research subjects contributing to these results by their participation (Macklin 2004).

At first glance, none of these ethical problems appears to arise in research subjects recruited for participation in epidemiologic or population-based studies.

Problem (a): Epidemiologic or population-based studies are not performed in patients but in individuals from the general population. Consequently, researchers do not owe their research subjects the same duty of personal care as in a physician-patient relationship.

Problem (b): Epidemiologic studies usually do not recruit subjects who are unable to give informed consent. Hence, epidemiologic study populations are not vulnerable. On the contrary, we can assume that participants in epidemiologic research have in fact been especially well informed, during the consent process, about all aspects of the study they are participating in. This does not imply that there are no incidental findings in pediatric research. On the contrary, it has been recognized that specific ethical problems arise when incidental findings are discovered in children (Wilfond and Carpenter 2008; Hens et al. 2011). These specific issues do not concern us here.

Problem (c): Unlike research in developing countries, epidemiologic studies do not violate the principle of fair selection of subjects. There is neither a financial incentive to attract persons in desperate economic circumstances,1 nor are the research participants excluded from ever being able to benefit from the research results in the future.

1.3.2 The Core of the Ethical Dilemma Posed by Incidental Findings

What has been said so far may suggest that there are no specific ethical and legal issues arising in association with epidemiologic research. At first sight, the central ethical problem with incidental findings appears to be a mere conflict between an ethical imperative and a methodological standard, where it seems obvious that the ethical imperative should carry greater weight. On closer scrutiny, however, this problem turns out to be a true ethical dilemma, i.e., a situation that requires a choice between two ethical principles which cannot both simultaneously be adhered to. While a similar ethical conflict can challenge clinical investigators, the choices available to the researcher for overcoming the conflict are different in clinical and epidemiologic studies. In the following, we elaborate on this ethical conflict and consider an example. In our opinion, the conflict is so grave that, unless an acceptable solution is found, it may threaten the legitimacy of population-based research.

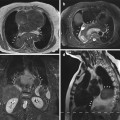

If we wish to come to terms with the methodological implications that lead to what we consider to be the core of the ethical dilemma posed by incidental findings, we must first recall how the design of population-based studies differs from that of clinical trials. Two aspects are important here. First, an epidemiologic study investigates a set of individuals recruited from the general population and not a set of patients, who are recruited for a clinical study with a specific diagnosis or an indication for a specific treatment. This is methodologically important because the primary goal of epidemiologic research is to obtain quantitative data on the natural history of diseases in the general population. The results are valid only if the sample investigated is truly representative of the general population in terms of those aspects that are relevant to the goal of the study. Second, we are here dealing with noninterventional studies. While a clinical study is usually conducted to investigate the safety and effectiveness of a medical intervention, population-based epidemiologic research is observational: the aim is to evaluate the health status of the research subject without performing any study-specific interventions.

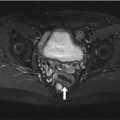

How then does the ethical dilemma arise? Let us consider an example. A whole-body MRI examination performed in the setting of an epidemiologic study reveals a kidney tumor that is still treatable if immediate measures are taken. It is undisputed that a finding of such import for the subject’s quality of life and life expectancy must be disclosed. The investigator’s moral obligation to act in the interest of the research subject in such a situation is not simply a matter of medical ethics. Even if study participation does not establish a physician-patient relationship between the investigator and the research subject, a direct duty of care and assistance arises when an incidental abnormality is so serious as to constitute an exigency (see Schleim et al. 2007, p 1044). This is the case when an incidentally detected abnormality is life-threatening.2 In such a situation, there is a general (limited) moral obligation to provide assistance, which is independent of a physician’s professional duties. According to German law, anyone who recognizes such a situation of exigency must provide assistance according to his or her ability. In a medical context, it is even more difficult to deny such an obligation because study subjects have often agreed to participate in the study precisely because they expect to receive the medical care necessary to deal with a critical finding revealed by the study-related examinations.3

While in the best interest of study subjects, the communication of incidental findings compromises the validity of the study. Each disclosure of an incidental finding alters the study sample such that the disease courses observed in the sample will systematically deviate from the natural evolution of disease in the general population. This conflicts with the primary aim of epidemiologic research, which is to observe how diseases evolve without interference from study-related interventions. Valid epidemiologic data can be derived from a study sample only if the subjects investigated are representative of the general population with regard to the aspects under investigation throughout the study. Once an incidental finding has been communicated to a study subject, it is no longer justified to assume that the sample is representative (Hoffmann 2013). The disclosure provides study subjects with information on their health that is not available to the general population, of which they are supposed to be representative. With this knowledge, they can seek treatment at an earlier time than would have been possible had they not participated in the study. Thus, medical interventions are different in the study population and in the general population, and disease evolution in the study population systematically deviates from that in the normal population. This is how disclosure of incidental findings results in a biased sample, compromising the validity of the study and generating knowledge that cannot be generalized to the normal population. Sample theory states that a systematic bias in a sample, as it may result from the disclosure of incidental findings, escapes the statistical methods used to estimate sampling errors. This means that such a systematic bias cannot be controlled by increasing the sample size (Schäffer 1996).

The so-called Literary Digest disaster in the USA is the classic example of a biased sample. The journal conducted a telephone survey among its readers in the 1936 presidential campaign between Alfred M. Landon und Franklin D. Roosevelt. As the Literary Digest was a fairly nonpolitical journal, it was assumed that the readership would not have a systematically biased preference for either of the candidates. The poll predicted a landslide victory for the Republican candidate, Landon, when in fact Roosevelt was reelected by a large margin. What was the reason for this wildly incorrect estimate of the vote despite the huge sample size of 2.3 million persons? It turned out later (Squire 1988) that conducting the survey by telephone had been the crucial error. In 1936, the people who had telephones were mostly people with high incomes, who also tended to vote Republican. Therefore, the choice of method led to a systematic selection bias. This poll also nicely illustrates the central issue that concerns us here: when a systematic sampling error occurs while a study is under way, this cannot simply be remedied by increasing the sample size. The Literary Digest

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree