The Gastrointestinal Tract: Small Bowel

The diagnosis of small-bowel diseases is a challenge to the clinician because of the overlapping of nonspecific symptoms.

Disorders affecting the small bowel are a significant cause of morbidity in infants and children, frequently requiring multiple imaging modalities for diagnosis. By enteroscopy, only 50% of small-bowel loops can be visualized. The radiologist, therefore, has come to play an important role in the evaluation of a variety of small-bowel conditions.

The plain radiograph examination is often the first radiologic investigation, particularly when obstruction or pneumoperitoneum is suspected in neonates. In young children, the differences of density are hardly pronounced, and loops are densely packed in a polygonal appearance. Air usually reaches the rectum by 24 hours after birth. Plain film with horizontal beam (supine, lateral decubitus, erect) may be essential to demonstrate free air and airfluid levels. Neonatal obstructions are classified as high or low. Obstructions that occur proximal to the middle ileum are called high or upper intestinal obstructions. Obstructions that involve the distal ileum or colon are called low intestinal obstructions. The distinction is critical because children with high obstructions usually need little or no radiologic evaluation after plain radio-graphs, and the specific diagnosis is made in the operating room. Newborns with low obstructions need a contrast enema, which usually provides a specific diagnosis and may be therapeutic. In older children, some authors prefer to start the abdominal investigation with US, because abdominal X-ray has less accuracy for usual pathologies (appendicitis, intussusception [IT], obstruction) and inherent radiation risk. Because abdominal symptoms are occasionally referred from lower lobe chest pathology, the diaphragmatic area should be adequately depicted on plain films.

Contrast examination, usually with barium, is a primary technique and widely used (despite its low index accuracy/cost benefits) because of the limitations of endoscopy in depicting the small bowel pathologies and the current decreased availability of MR enterography exams. The goal of barium examination is to establish the presence or absence and the nature of the disease with a minimal radiation dose. The transit time takes a mean of 70 minutes. Rarely used today, an enteroclysis examination can depict the entire small bowel, including mucosal detail and smaller luminal defects. The use of MRI to do the same is currently being investigated.

On cross-sectional techniques, the small-bowel wall is thin, usually less than 3 to 4 mm.

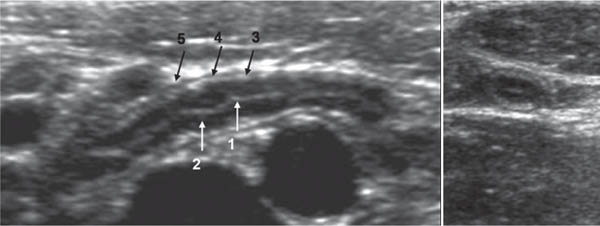

By US, the bowel wall appears mostly as a hypoechoic band limited by two hyperechoic surfaces and divided by a hyper-echoic line, which is the submucosa. Sonography may visualize five concentric layers of alternating echogenic/hypoechoic layers from the lumen outward ( Fig. 2.75 ).

MRI and CT are indicated to determine the extent of a lesion for masses and trauma, provide important 3D information about the extraluminal component of bowel disease, the relationships to adjacent organs, as well as vascular information. Accurate imaging of the small bowel requires the administration of both intravenous and oral contrast medium, sometimes by enteroclysis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree