The Male Breast

Our approach to male patients presenting with breast-related symptoms includes marking the area of concern with a metallic BB and obtaining craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views of the symptomatic side. After reviewing of these images, we may obtain views of the contralateral breast for comparison. If benign changes are diagnosed, no further evaluation is undertaken. Spot compression and magnification views are obtained as needed for evaluation of findings suggestive of an underlying cancer.

Mammographically, the normal male breast is predominantly fatty with prominent pectoral muscles and a small nipple. Male breast tissue is primarily composed of subareolar ducts with no significant branching and sparse surrounding stroma. Lobular units are rare in men. Consequently, lesions arising in the lobules such as cysts, fibroadenomas, and sclerosing adenosis are unusual in men not taking exogenous estrogen (e.g., for prostate cancer treatment). All of the lesions discussed for female patients can occur in male patients, however, with a significantly lower incidence (particularly the lobular-derived lesions).

The principles for positioning the breast described for female patients apply to male patients. The compression paddle used routinely for screening studies can make it difficult for the technologist to hold the male breast in place as compression is applied. The technologist may find it difficult to slide her hand out from under the paddle as compression is applied without scraping her knuckles or letting go of the breast prematurely. Some equipment manufacturers provide a paddle that is half the width of the standard compression paddle for imaging male patients (these paddles are also useful in women with implants for the implant-displaced views).

Breast imaging studies in men are scheduled as diagnostics because the patients present with breast-related symptoms. Cooper and associates (1) suggest that mammography is not necessary in male patients younger than 50 years of age who present with diffuse breast enlargement or a palpable nonindurated central subareolar mass, unless there are other strong clinical indications such as skin changes or bloody nipple discharge. In their series, none of 43 male patients younger than 50 years of age were found to have breast cancer (1). Although there are no significant data supporting screening mammography in men, it may be something to consider in men who have a personal history of breast cancer or in families with male breast cancer and the BRCA2 gene.

Enlargement of the male breast with secondary branching of subareolar ducts and proliferation of the surrounding stroma is termed gynecomastia. This process can be unilateral or bilateral, symmetric or asymmetric.

GYNECOMASTIA

Gynecomastia is common, reportedly occurring in 57% of men older than 44 years of age (2). Gynecomastia is the enlargement of the male breast with secondary branching of the

subareolar ducts and proliferation of the surrounding stroma. Patients present with a subareolar mass that may be tender. The process may be unilateral or bilateral, symmetric or asymmetric. Cooper and colleagues (1) described unilateral involvement in 33% of their patients with gynecomastia, and in another 33% involvement was asymmetric. Appelbaum and co-workers (2) reported 61 patients with gynecomastia, 55 of whom had bilateral mammograms. In 84% of the patients, the gynecomastia was asymmetric; in 2%, it was symmetric; and in 14%, it was unilateral. Increases in serum estradiol levels, combined with decreases in testosterone levels, are thought to be the etiologic factors governing the development of gynecomastia. At this time, there is no known association between gynecomastia and male breast cancers. Some of the causes of gynecomastia are listed in Box 9.1.

subareolar ducts and proliferation of the surrounding stroma. Patients present with a subareolar mass that may be tender. The process may be unilateral or bilateral, symmetric or asymmetric. Cooper and colleagues (1) described unilateral involvement in 33% of their patients with gynecomastia, and in another 33% involvement was asymmetric. Appelbaum and co-workers (2) reported 61 patients with gynecomastia, 55 of whom had bilateral mammograms. In 84% of the patients, the gynecomastia was asymmetric; in 2%, it was symmetric; and in 14%, it was unilateral. Increases in serum estradiol levels, combined with decreases in testosterone levels, are thought to be the etiologic factors governing the development of gynecomastia. At this time, there is no known association between gynecomastia and male breast cancers. Some of the causes of gynecomastia are listed in Box 9.1.

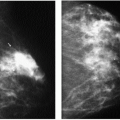

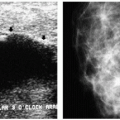

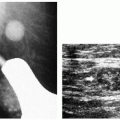

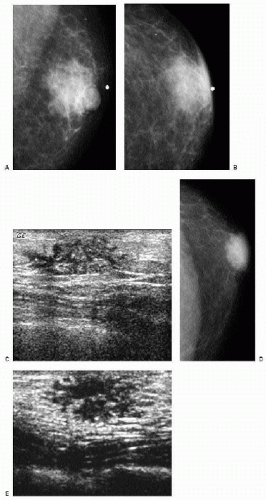

Three patterns have been described for gynecomastia mammographically (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). The nodular pattern is characterized by increased tissue focally in the subareolar area (Figure 9.1) that fans out symmetrically from the nipple. It has been suggested that this represents the early phase of gynecomastia and corresponds to florid gynecomastia histologically. The epithelial lining of the ducts is hyperplastic, and the surrounding stroma is edematous, loose, and cellular. The fibrous or dendritic pattern appears as retroglandular tissue with prominent fibrous extensions that radiate out into the fatty tissue (Figure 9.2). Histologically, this is fibrous gynecomastia and reflects long-standing changes; there is ductal proliferation with dense fibrotic stroma. Diffuse glandular gynecomastia is the third pattern; it simulates the heterogeneously dense female breast pattern (Figure 9.3). Appelbaum and co-workers (2) described 61 patients with histologically proven gynecomastia: 77% had nodular, 20% dendritic, and 3% diffuse patterns mammographically. In some men presenting with breast enlargement and tenderness, fatty tissue alone is imaged mammographically (Figure 9.4).

Box 9.1: Causes of Gynecomastia

Idiopathic

Physiologic

Neonatal (placental estrogens)

Puberty (imbalance in androgen-to-estrogen ratio)

Elderly (decreases in plasma testosterone levels)

Diseases with estrogen excess

Testicular tumors (Leydig cell, Sertoli cell, testicular germ cell)

Nontesticular tumors (lung, liver, renal, adrenocortical, hepatocellular)

Cirrhosis

Endocrine abnormalities (hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism)

Nutritional deprivation

Androgen deficiency

Aging

Primary hypogonadism; Klinefelter’s syndrome (XXY)

Secondary hypogonadism (trauma, orchitis, cryptorchidism, irradiation, hydrocele)

Renal failure (and hemodialysis)

Drugs

Estrogenic activity (anabolic steroids, exogenous estrogen—diethylstilbestrol for prostate cancer, digitalis, heroin, marijuana, alcohol)

Inhibition of testosterone action or synthesis (cimetidine, diazepam, phenytoin, spironolactone, vincristine, methotrexate)

Idiopathic mechanism (furosemide, isoniazid, methyldopa, nifedipine, reserpine, theophylline, verapamil)

Systemic disorders (unknown mechanism)

Nonneoplastic diseases of the lung

Chest wall trauma

Human immunodeficiency virus

Figure 9.1 Gynecomastia, nodular pattern. Mediolateral oblique (A) and craniocaudal (B) views in a 94-year-old male patient presenting with a palpable mass. Metallic BB marks the area. Round glandular tissue is imaged corresponding to the mass. Scalloping of the density is noted, consistent with tissue. C. Ultrasound demonstrates hypoechoic, serpiginous, tubular-like tissue radiating out symmetrically from under the nipple. No cystic or solid masses are imaged when correlating clinical and imaging findings. D. In this 72-year-old male patient, the craniocaudal view demonstrates round glandular tissue, symmetrically centered on the nipple. E. Ultrasound demonstrates hypoechoic, serpiginous, tubular-like tissue radiating out symmetrically from under the nipple and corresponding to the area of concern in the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|