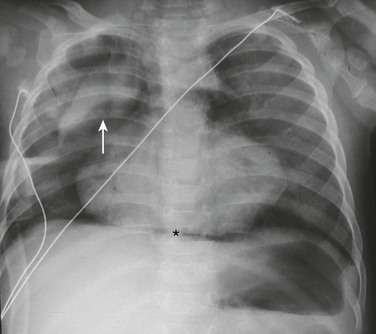

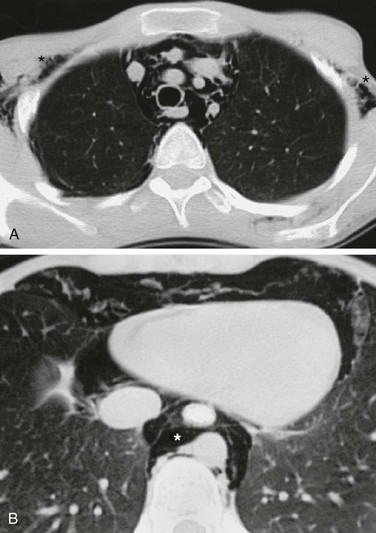

Chapter 58 Pneumomediastinum, also known as mediastinal emphysema, is a condition in which air is present within the mediastinum.1 Pneumomediastinum occurs more frequently in infants than in older children.2 Affected pediatric patients typically present with a sensation of retrosternal fullness, dysphagia, sore throat, chest pain, or dyspnea. Etiology: Pneumomediastinum may be spontaneous or iatrogenic. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum results from a sudden forceful increase in intraalveolar pressure such as forceful inhalation or the Valsalva maneuver. In this instance, an alveolus can rupture, allowing gas under pressure into the low-pressure pulmonary interstitial compartment. The air then travels via the peribronchovascular space medially toward the hilum, which opens into the mediastinum.3,4 Occasionally, the air dissects along the lymphatics as well and extends to the visceral pleura, where a concomitant pneumothorax may occur. Iatrogenic pneumomediastinum may result from abdominal and cardiac surgery, endotracheal intubation, or cardiac catheterization. Additionally, pneumomediastinum also can occur after foreign body ingestion, trauma to the neck or chest, or any disruption of the tracheobronchial tree or esophagus (e.g., Boerhaave syndrome).2 It is not uncommon for pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax to coexist.5 This phenomenon sometimes can be attributed to a common mechanism of injury, or the pneumothorax may arise as a result of a pneumomediastinum. In addition, potential communications between the mediastinum and the peritoneal cavity exist via anatomic diaphragmatic defects, such as the esophageal hiatus. As such, the pneumoperitoneum can dissect superiorly into the mediastinum and vice versa. Retroperitoneal extension of the pneumomediastinum also may be observed.6 Rarely, air within the mediastinum can enter the spinal canal, which is termed pneumorrhachis.7 Imaging: The air within the mediastinum typically displaces the pleura and lung laterally (Fig. 58-1). It may decompress into the superior mediastinum and dissect along fascial planes into the subcutaneous tissues of the neck and retropharynx (e-Fig. 58-2). In infants and younger children, air within the mediastinum may displace the thymus superiorly to produce the “spinnaker sail” sign (see Fig. 58-1). Figure 58-1 Pneumomediastinum in a 6-month-old boy. e-Figure 58-2 Pneumomediastinum in a 2-year-old girl. With small pneumomediastinum, sometimes only a sliver of curvilinear radiolucency is seen adjacent to the cardiac border, most often on the left. This sliver may sharply outline the aortic arch and descending aorta. When air is adjacent to the pulmonary artery or a branch (typically on the right), the “ring around the artery” sign is seen on the lateral view.6,8 The often-quoted “continuous diaphragm sign” results from air interposed between the pericardium and the diaphragm,8 which effectively erases the normal “silhouetting” of the diaphragm that allows it to be visualized as the single structure that it is. A large pneumomediastinum may be confused with a pneumothorax, especially when the patient undergoes imaging while in the supine position. In such an equivocal situation, a decubitus radiographic view may be helpful because the mediastinal air does not move, whereas the pneumothorax rises nondependently.5 At times, pneumomediastinum may be difficult to differentiate from pneumopericardium. In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium does not lift the thymus or outline the aortic arch. The air is contained by the pericardium, which can have a dome-shaped superior margin. Pneumopericardium is almost always seen in association with pneumomediastinum except after open-heart surgery.5 Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment of pneumomediastinum is aimed at the underlying cause. For most spontaneous cases of pneumomediastinum, treatment is supportive, including rest, pain control, and avoidance of Valsalva maneuvers.2 If concern exists about the possibility of esophageal rupture, an esophagram using water-soluble contrast may be performed, and a timely surgical consultation should be obtained when the possibility of rupture is present.9,10 Very rarely, pseudotamponade, laryngeal compression, tension pneumomediastinum, tension pneumothorax, or mediastinitis occur and require surgical intervention. Etiology: Mediastinal hemorrhage in pediatric patients usually is due to venous bleeding from blunt trauma.5 Large mediastinal hemorrhage as a result of mediastinal vessel rupture often is due to iatrogenic causes related to central catheter placement or cardiothoracic procedures in pediatric patients. However, mediastinal hemorrhage in children also can occur spontaneously in the context of hemophilia, in which case the hemorrhage may be retropharyngeal and dissect into the mediastinum.5,11 Additionally, rare cases of neonatal thymic hemorrhage have been reported,12 possibly related to vitamin K deficiency.13,14 Imaging: Although imaging findings of mediastinal hemorrhage may be nonspecific, the possibility of mediastinal hemorrhage should be considered when mediastinal widening, blurring of the aortic stripe margin, deviation of a nasoenteric tube, and/or left apical “capping” are present on chest radiographs (Fig. 58-3, A). When evaluating mediastinal widening on chest radiographs, attention must be paid to the technique (i.e., the portable anteroposterior vs. standard posterolateral view). A portable anteroposterior chest radiograph may exaggerate the size of the mediastinum. Therefore in equivocal cases, confirmation with a subsequent posterolateral view or a cross-sectional imaging study such as computed tomography (CT) may be necessary. On CT, mediastinal fluid with a Hounsfield unit greater than water (>20 HU) suggests mediastinal hemorrhage (Fig. 58-3, B). Figure 58-3 A mediastinal hematoma in a 2-year-old girl after open-heart surgery. Treatment and Follow-up: When mediastinal hemorrhage is considered on chest radiographs, further imaging studies such as echocardiography and/or contrast-enhanced CT using CT angiography protocol with subsequent multiplanar and three-dimensional reconstruction evaluation is warranted. With rapid clinical deterioration, urgent surgical exploration is an option to avoid delaying proper treatment. Infections arising de novo in the mediastinum are rare in the pediatric population. Mediastinal infections can be classified into two types: acute and chronic fibrosing mediastinitis. Whereas acute mediastinal infections usually are due to perforation of the esophagus and/or trachea with subsequent cellulitis or abscess formation,15,16 chronic fibrosing mediastinitis typically results from tuberculosis or Histoplasmosis infections.17–19 Etiology: Acute superior mediastinal infections typically are due to cervical infection or sternoclavicular osteomyelitis.20–22 The frequent underlying causes for acute anterior and middle mediastinal infections in pediatric patients include the incorrect passage of instruments (e.g., a nasogastric tube or endotracheal tube), impacted foreign bodies, child abuse, or leakage at the sites of surgical anastomoses.23 Posterior acute mediastinal infections usually are due to the extension of osteomyelitis of the vertebrae. Affected pediatric patients typically present with pain, fever, and an elevated white blood cell count. Imaging: Plain radiographic findings of acute mediastinitis are nonspecific. However, mediastinal widening, obliteration of normal mediastinal contours, and displaced or narrowed trachea should suggest possible underlying acute mediastinitis in the appropriate clinical setting. The more specific radiological imaging finding of acute mediastinitis is the presence of gas within the mediastinum, which can be better evaluated with CT. CT also can show complications from acute mediastinitis such as mediastinal abscess formation or empyema (Fig. 58-4). Figure 58-4 Acute mediastinitis resulting from a retropharyngeal abscess in a 1-year-old boy. Etiology: Chronic fibrosing mediastinitis, also known as sclerosing mediastinitis, is rare in the pediatric population. It is a condition characterized by abnormal proliferation of dense acellular collagen and fibrous tissue in the mediastinum.26,27 Although it is most frequently attributed to the sequelae of granulomatous infection such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Histoplasmosis infection, it also can arise as an idiopathic condition or as the sequelae of autoimmune disease, radiotherapy, or drugs such as methysergide and metoprolol.25,28 Additionally, chronic fibrosing mediastinitis also is associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing cholangitis, Riedel thyroiditis, and pulmonary granuloma.29 Affected pediatric patients often present with respiratory distress related to airway narrowing, dysphagia due to esophageal compromise, and/or facial and neck swelling resulting from obstruction of the superior vena cava. Imaging: The widening of the mediastinum with a lobular paratracheal and/or subcarinal mass that may be calcified is a typical imaging finding on chest radiographs. CT imaging findings of chronic fibrosing mediastinitis can be categorized into two patterns: focal or diffuse.26,30 Patients affected with focal-type chronic fibrosing mediastinitis typically present with a soft tissue mass, often associated with calcification (63%),30 that is located in the right paratracheal, subcarinal, or hilar regions (Fig. 58-5). On the other hand, pediatric patients affected with diffuse-type chronic fibrosing mediastinitis present with a diffusely infiltrating mass without calcification that often affects entire mediastinal compartments. Figure 58-5 Chronic fibrosing mediastinitis in a 17-year-old girl. Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment of acute mediastinitis consists of the administration of antibiotics that target the offending organisms. Localized mediastinal abscess formation due to acute mediastinitis can be managed with either a surgical or percutaneous abscess drainage procedure. Although no consensus or widely accepted guidelines currently exist for the treatment of chronic fibrosing mediastinitis, systemic antifungal or corticosteroid treatment, surgical resection, and local therapy for complications are the management options currently available. Surgical resection may be necessary for symptomatic pediatric patients who have extensive and aggressive chronic fibrosing mediastinitis that results in either obstruction or compression of mediastinal structures such as central airways, the esophagus, or mediastinal large vessels. The mediastinum is the most common location of chest masses in the pediatric population. Mediastinal masses in infants and children can be benign or malignant neoplasms, congenital anomalies, infections, vascular malformations, or pseudomasses. As with adult patients, it is useful to locate the mediastinal mass within one of the three mediastinal compartments (anterior, middle, or posterior) (Fig. 58-6). However, such a system of compartmentalizing the mediastinum may have shortcomings. For example, the borders of the anterior, middle, and posterior mediastinum, which are defined by anatomic landmarks as assessed on a lateral radiograph of the chest, do not have true and definite fascial planes. In addition, several disorders that may present as mediastinal masses cross boundaries or arise in multiple compartments. Nonetheless, the practice of assigning a mediastinal mass to a specific mediastinal compartment is still useful because such a method enables one to formulate a manageable differential diagnosis and effectively direct further imaging workup, and it yields valuable information, particularly for surgical planning. Figure 58-6 Anatomic landmarks demarcating the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments of the mediastinum labeled on a lateral chest radiograph. Congenital Abnormalities of the Thymus: Etiology: The thymus is a bilobed organ that serves as the site of T-cell maturation. The thymus develops from the third pharyngeal pouch. It begins a process of caudal and ventromedial elongation during the seventh and eighth week of gestation whereby the two sides fuse at about the level of the aortic arch. Partial failure of descent may result in ectopic thymic tissue in the neck or superior mediastinum. Absence of the thymus is a component of DiGeorge syndrome,31 with an incidence of 1 per 2000 to 4000.32–34 Imaging: The appearance of the thymus on frontal chest radiographs is variable and largely dependent on the age of the patient (Fig. 58-7).5,35,36 The thymus is prominent in size with a quadrilateral shape and convex margins during infancy (Fig. 58-8). After approximately the fifth year of life, the thymus becomes more triangular in shape with straight margins (e-Fig. 58-9). By the age of 15 years, the margins of the thymus are either straight or concave (Fig. 58-10). Absent thymic tissue in pediatric patients with DiGeorge syndrome is usually evident on chest radiographs in infants and young children. However, an atrophic thymus due to a stress response may appear similarly.37,38 The clinical context is often helpful in distinguishing these two conditions without the need for cross-sectional studies. Figure 58-7 A normal thymus in a female neonate. Figure 58-8 A normal thymus in a 5-month-old girl. Figure 58-10 A normal thymus in an adolescent boy. e-Figure 58-9 A normal thymus in a 5-year-old boy. Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment of DiGeorge syndrome is targeted to the associated defects such as hypocalcemia, frequent infections, and conotruncal cardiac defects. Because DiGeorge syndrome is a component of the 22q11 deletion syndrome, many patients with this syndrome also have velocardiofacial syndrome.39 Normal Variants of the Thymus: Etiology: The two most common anatomic variants of the thymus are either superior or posterior extension of the normal thymus (e-Fig. 58-11 and Fig. 58-12). These variants usually are seen before 2 years of age. The thymus may extent superiorly to the level of the lower neck40,41 or posteriorly to the middle or posterior mediastinal compartment.42,43 The posterior extension of the thymus typically is posterior to the superior vena cava on the right or the aortic arch on the left. After puberty, the thymus undergoes slow involution. During stress, a rapid transient decrease in the size of the gland occurs, and it regains its original size after the offending mechanism (e.g., intubation, surgery, or chemotherapy) is withdrawn—the so-called thymic rebound.38,44 Figure 58-12 Posterior thymic extension as a normal variant in a 1-year-old boy. e-Figure 58-11 Normal superior extension of thymic tissue into the neck. Imaging: An ectopic thymus rarely presents as a mass and is most commonly discovered incidentally as thymic tissue extension on cross-sectional imaging with similar signal characteristics and density as the orthotopic thymus on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT, respectively (see e-Fig. 58-11 and Fig. 58-12). Occasionally, however, retrocaval thymus may be mistaken for a mediastinal mass on radiographs. With superior mediastinal extension, the diagnosis may be made with ultrasound using a high-frequency linear array transducer. The ectopic thymus should exhibit homogenous echotexture with internal bright specular reflections, similar to the orthotopic thymus.45 Further, contiguity with the orthotopic thymus may be demonstrated on ultrasound. The appearance of rebound thymus on chest radiographs may be impressive in terms of degree and rapidity of development. Any displacement or compression of adjacent airway or vessels by the thymus should raise suspicion for a neoplasm. Etiology: A thymic cyst is a rare, fluid-filled lesion typically representing a cystic remnant of the thymopharyngeal duct.38,46 Although a thymic cyst can occur anywhere from the pyriform sinus to the anterior mediastinum, it is most commonly found in the lateral infrahyoid neck region.47 A fibrous cord may connect the thymic cyst to the mediastinal thymus. When the cyst is large, affected pediatric patients present with a slowly enlarging neck mass that may be associated with respiratory compromise, dysphagia, or vocal cord paralysis. Although most thymic cysts are derived from a remnant of the thymopharyngeal duct, thymic cysts also have been described in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus and in patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving the thymus.48,49 Cysts in the latter group may feature small calcifications.50 Imaging: Thymic cysts appear as a spherical, fluid-filled lesion or as multilocular cystic spaces with a thin wall. The thymic cyst is usually occult on chest radiographs. In infants and young children, ultrasound may confirm the fluid-filled nature of the mass. On CT and MRI, thymic cysts typically present as a nonenhancing cystic mass (e-Fig. 58-13). The MR signal of a thymic cyst is variable depending on whether the contents are proteinaceous and/or hemorrhagic. The differential diagnosis of a thymic cyst in pediatric patients includes branchial cleft cyst, lymphatic malformation, thyroglossal duct cyst, dermoid cyst, bronchogenic cyst, and teratoma. e-Figure 58-13 A thymic cyst in a 2-year-old girl. Etiology: A thymolipoma is an uncommon benign thymic mass composed of both thymic and mature adipose tissue. Thymolipomas account for approximately 2% to 9% of all thymic neoplasms.38,51 The presumed underlying etiologies include a variant of a thymoma, hyperplasia of mediastinal fat, and a neoplasm of mediastinal fat that encases thymic tissue.51,52 Affected patients typically are asymptomatic because a thymolipoma is very soft and pliable, exerting little mass effect.

The Mediastinum

Spectrum of Mediastinal Anomalies and Abnormalities

Overview

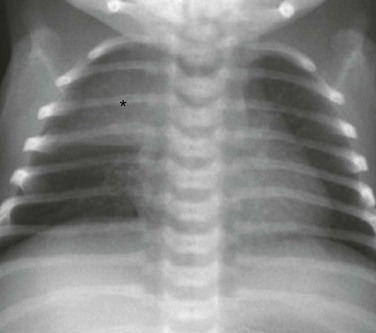

A frontal chest radiograph demonstrates a lifted thymic shadow (arrow), the so-called “spinnaker sail sign.” Mediastinal air (asterisk) also is interposed between the central diaphragm and pericardium, and lucency is seen surrounding the heart.

A, An axial lung window computed tomography (CT) image at the level of the superior mediastinum shows mediastinal air that outlines major vessels and fascial planes. Air has dissected through the soft tissues and is seen bilaterally in the axilla (asterisks). B, An axial lung window CT image at the level of the lower thorax demonstrates further caudal extent of the mediastinal air (asterisk).

Mediastinal Hemorrhage

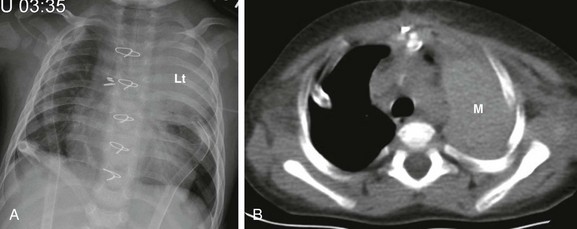

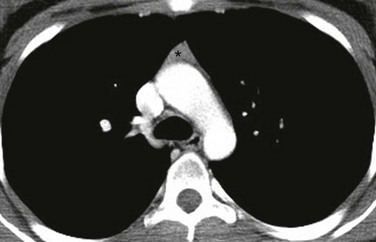

A, A frontal chest radiograph shows large left upper lung zone opacity (Lt). No ipsilateral mediastinal shift or other evidence suggestive of atelectasis is present. Also noted are bilateral chest tubes, median sternotomy wires, and surgical clips within the mediastinum. B, An axial unenhanced computed tomography image at the level of the upper thorax reveals a large, left-sided, high-attenuation, masslike area (M) in the left extrapleural (mediastinal) space, indicative of a postprocedural mediastinal hematoma.

Mediastinal Infection

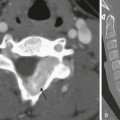

Acute Mediastinitis

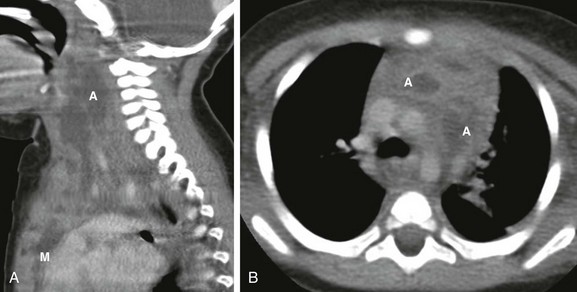

A, A sagittal enhanced multiplanar computed tomography (CT) image through the neck shows a large, complex fluid collection (A) extending caudally into the mediastinum (M). B, An axial enhanced CT image obtained at the level of the aortic arch demonstrates two of the better defined abscesses (A) in the anterior mediastinal compartment embedded in an inflamed and heterogenous thymus.

Chronic Fibrosing Mediastinitis

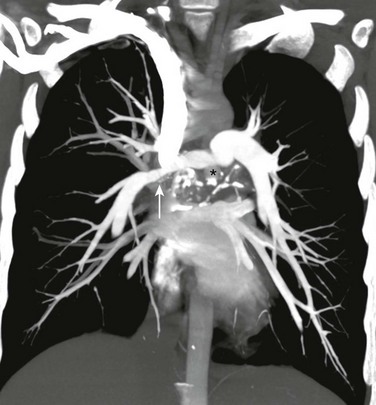

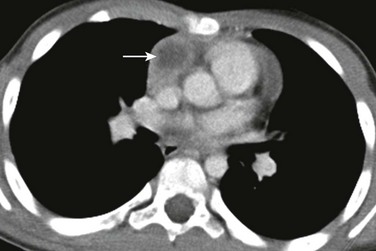

A coronal maximum intensity projection computed tomography image of the chest shows a middle mediastinal ill-defined mass that narrows the right pulmonary artery (arrow). Also note the calcifications (asterisk). (From Daltro PA, Santos EN, Gasparetto TD, et al. Pulmonary infections. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41(Suppl 1):S69-S82.)

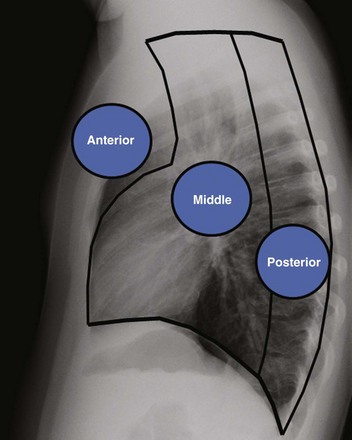

Mediastinal Masses

Anterior indicates the anterior mediastinal compartment, Middle indicates the middle mediastinal compartment, and Posterior indicates the posterior mediastinal compartment.

Anterior Mediastinal Masses

The frontal chest radiograph shows a thymic sail sign, which is created by the right lobe of the thymus (asterisk) abutting the minor fissure.

An axial enhanced computed tomography image at the level of the aortic arch shows the expected appearance of the thymus (asterisk) in the anterior mediastinal compartment at this age. The thymus has a quadrilateral shape and a convex margin. It is homogeneous in attenuation without an associated cystic, calcific, or fat component.

An axial enhanced computed tomography image at the level of the aortic arch shows the expected appearance of the thymus (asterisk) in the anterior mediastinal compartment at this age. The thymus has a triangular shape with a straight margin.

An axial enhanced computed tomography image at the level of the aortic arch shows the expected appearance of the thymus (asterisk) in the anterior mediastinal compartment at this age.

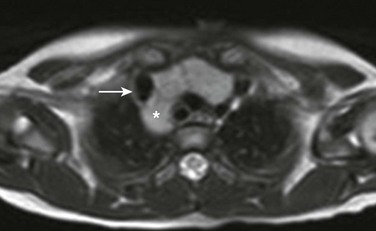

An axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image at the level of the brachiocephalic vein shows posterior extension (asterisk) of the thymus behind the superior vena cava (arrow).

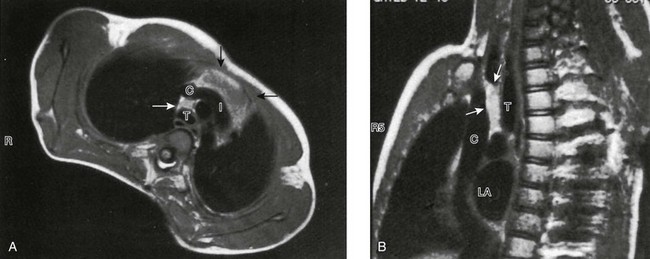

On this gated axial (A), oblique (B), mildly T1-weighted magnetic resonance images, the thymus is clearly distinguished from vessels. It is of intermediate signal intensity—less than fat but greater than muscle. Note how far cephalad to the innominate vein (I) the thymic tissue extends (arrows). C, superior vena cava; T, trachea; LA, left atrium.

An axial enhanced computed tomography image at the level of the main pulmonary artery shows a round hypoattenuating lesion (arrow) consistent with a cyst in the thymus. Surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of a thymic cyst.