5 The pancreas

The normal pancreas

Ultrasound techniques

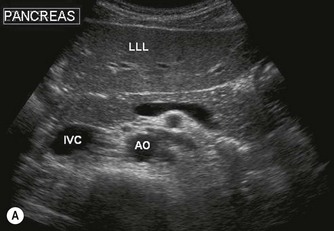

The operator must make the best use of acoustic windows, different patient positions and various techniques to fully investigate the pancreas. Start by scanning the epigastrium in transverse plane, using the left lobe of the liver as an acoustic window. Using the splenic vein as an anatomical marker, the body of the pancreas can be identified anterior to this. The tail of pancreas is slightly cephalic to the head, so the transducer plane should be accordingly oblique to display the whole organ (Fig. 5.1). Different transducer angulations display different sections of the pancreas to best effect.

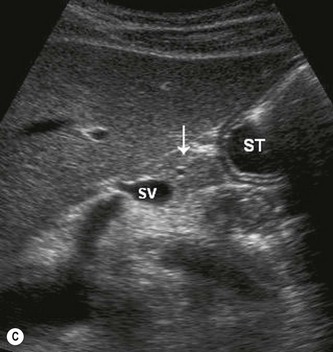

(B) The normal pancreatic duct (arrow) is seen in the body of the pancreas.

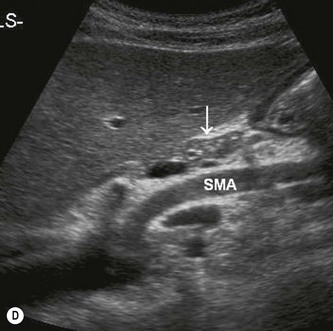

(D) The body of the pancreas (arrow) lies anterior to the SMA.

(G) The lower end of the CBD (arrow) as it goes through the HOP (arrowheads).

Identify the echo-free splenic vein and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) posterior to it. The latter is surrounded by an easily visible, hyperechoic fibrous sheath. The pancreas is ‘draped’ over the splenic vein (Fig. 5.1).

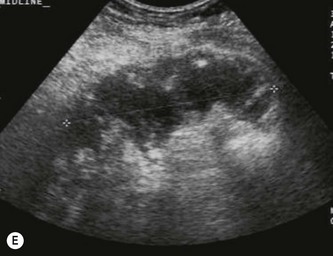

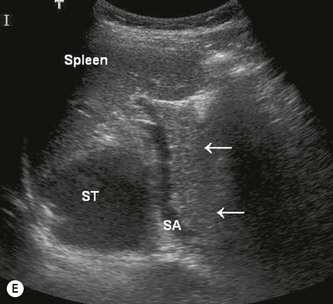

Where possible, use the left lobe of the liver as an acoustic window to the pancreas, angling slightly caudally. The tail, which is often quite bulky, may require the transducer to be angled towards the patient’s left. The spleen also makes a good window to the tail in coronal section (Fig. 5.1E). If you can’t see the pancreatic head properly, turn the patient left side raised, which moves the duodenal gas up towards the tail of the pancreas. Right side raised may demonstrate the tail better. If these manoeuvres still fail to demonstrate the organ fully, try:

Ultrasound appearances

The texture of the pancreas is rather coarser than that of the liver.

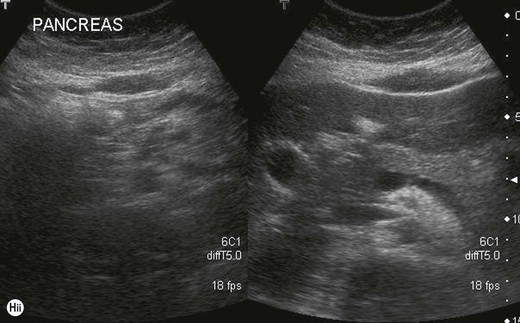

The echogenicity of the normal pancreas alters according to age. In a child or young person it may be quite bulky and relatively hypoechoic when compared with the liver. In adulthood, the pancreas is hyperechoic compared with normal liver, becoming increasingly so in the elderly, and tending to atrophy (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2 • Age-related acoustic appearances:

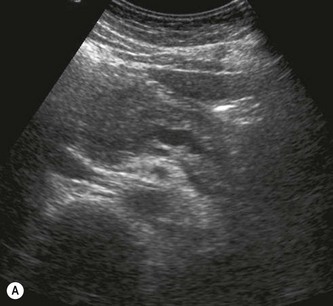

(A) Pancreas in a young person, demonstrating normal hypoechogenicity.

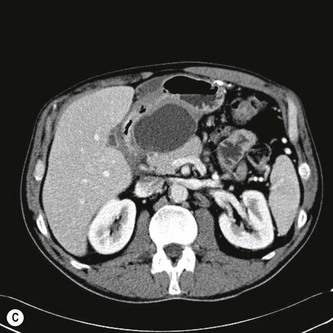

(C) The pancreas becomes hyperechoic and infiltrated with fat in an older patient.

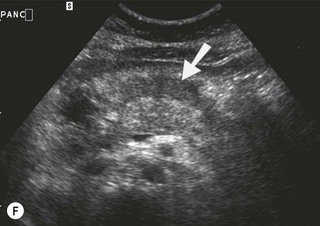

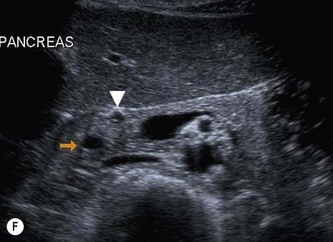

The main pancreatic duct is most easily visualized in the body of pancreas, where its walls are perpendicular to the beam. The normal diameter is 2 mm or less. The CBD can be seen in the lateral portion of the head, and the gastroduodenal artery lies anterolaterally (Fig. 5.1F). The size of the uncinate process varies.

Other imaging

MRCP is increasingly used to examine the pancreatic duct1 due to its relative non-invasive nature and low risk compared with ERCP.2,3 ERCP is invasive and carries a small risk of post-procedure pancreatitis or, rarely, perforation, and so is reserved for therapeutic procedures such as the placement of a stent.

EUS is an increasingly useful modality for imaging the pancreas in detail, without the problems of intervening stomach or duodenal gas. This technique is helpful for imaging the pancreas in pancreatitis and has also been shown to be superior to CT in detecting occult neoplasms.4 The proximity of the endoscope to the pancreas and ducts improves sensitivity and specificity for tiny stones and lesions. It also has the facility to take a biopsy if required (Fig. 5.4D), which can be accurately directed towards the area of interest, improving histological yield.

CT is most commonly used as a second-line investigation, following initial transabdominal ultrasound, especially in the presence of dilated biliary ducts. In addition to identifying pancreatic masses, it is also used to stage patients with pancreatic carcinoma. CT is generally the imaging of choice in severe acute pancreatitis, and is able to detect pancreatic necrosis, although the use of contrast ultrasound may also have a useful role in assessing vascularity,5 diagnosing necrosis and even in identifying tumours, allowing further imaging to be directed more appropriately.

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis

Clinical features

Acute inflammation of the pancreas has a number of possible causes (Table 5.1), but is most commonly associated with gallstones or alcoholism.

Table 5.1 Causes of acute pancreatitis

| Biliary calculi | Most common cause. Obstructs the main pancreatic duct/papilla of Vater and may cause reflux of bile into the pancreatic duct |

| Alcoholism | Alcohol overstimulates pancreatic secretions causing overproduction of enzymes |

| Trauma/iatrogenic | Damage/disruption of the pancreatic tissue, e.g. in a road traffic accident, or by surgery, biopsy or ESWL6 |

| Drug induced | A relatively uncommon cause. Some anti-cancer drugs can cause chemical injury |

| Infection | E.g. mumps. A rare cause of pancreatitis |

| Congenital anomaly | Duodenal diverticulum, duodenal duplication, sphincter of Oddi stenosis or choledochal cyst may obstruct the pancreatic duct, giving rise to pancreatitis |

| Hereditary | A rare, autosomal dominant condition presenting with recurrent attacks in childhood or early adulthood |

ESWL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy.

Ultrasound appearances

Mild acute pancreatitis may have no demonstrable features on ultrasound, especially if the scan is performed after the acute episode has settled. Although ultrasound is used to assess the pancreas in cases of suspected acute pancreatitis, its main role is in demonstrating the cause of the pancreatitis, for example biliary calculi, in order to plan further management. The ultrasound finding of microlithiasis or sludge in the gallbladder is highly significant in cases of suspected pancreatitis7 (see Chapter 3) and is often implicated in the cause of recurrent pancreatitis.

Acute idiopathic pancreatitis (AIP) is a term used when the cause of pancreatitis has not been demonstrated, although the majority of these do turn out to have microlithiasis or biliary sludge. Improved ultrasound imaging is more readily able to detect microlithiasis, and EUS is particularly useful in such cases, as it is more sensitive in detecting tiny stones in the CBD. In more severe cases the pancreas becomes enlarged and hypoechoic due to oedema. The main duct may be dilated or prominent (Fig. 5.3).