The Temporal Bone

Lindell R. Gentry

L. R. Gentry: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

THE TEMPORAL BONE

During the first half of the 20th century, the radiographic examination of the temporal bone was accomplished by the use of conventional film techniques. Since 1980, however, thin-section high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) has effectively supplanted other techniques by virtue of its inherently higher contrast resolution.

CONVENTIONAL RADIOGRAPHY

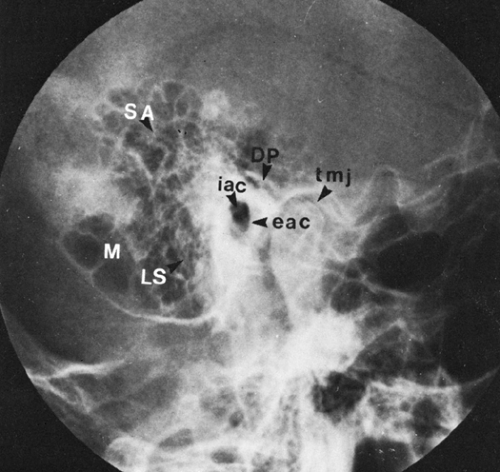

When conventional radiography was the only method available for imaging of the temporal bone, many projections were devised to minimize the interference produced by the adjacent bones of the skull. Lateral, oblique, anteroposterior, and semiaxial views and modifications of these views were produced by angulation of the x-ray beam or the patient’s head. The lateral mastoid view (Fig. 38-1) is the only projection still used in some imaging centers, largely to confirm a diagnosis of acute mastoiditis or substantiate previous mastoid disease.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY OF THE TEMPORAL BONE

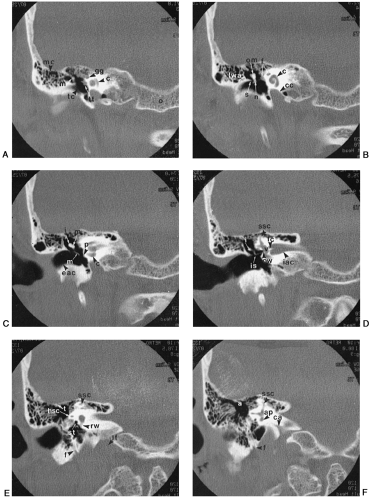

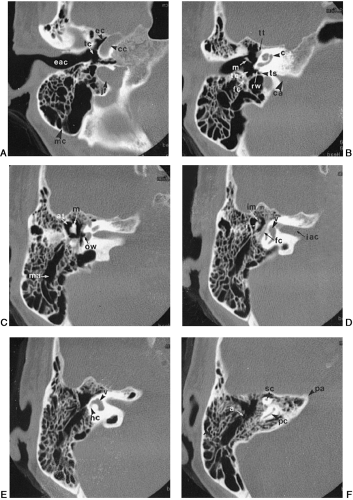

Computed tomography (CT) of the temporal bone requires very thin sections (1 to 2 mm), a small field of view (less than 10 cm), and a high-spatial-resolution reconstruction algorithm. It is best to use low milliampere-seconds (less than 240 mAs) and short scan times (less than 1 second). Representative axial and coronal CT scans are illustrated in Figs. 38-2 and 38-3. CT is currently the study of choice for evaluating the temporal bone.1,4,5

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The temporal bone consists of five parts: squamous, mastoid, petrous, tympanic, and styloid process. The squamous portion forms a part of the lateral aspect of the cranial vault, and the petrous portion creates the division between the middle and posterior cranial fossae and contains the structures of the inner ear. The tympanic portion contributes primarily to the external ear canal, and the mastoid consists chiefly of air cells. The styloid process serves as a point of origin for the styloid group of muscles and ligaments.1,4,5

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES OF THE TEMPORAL BONE

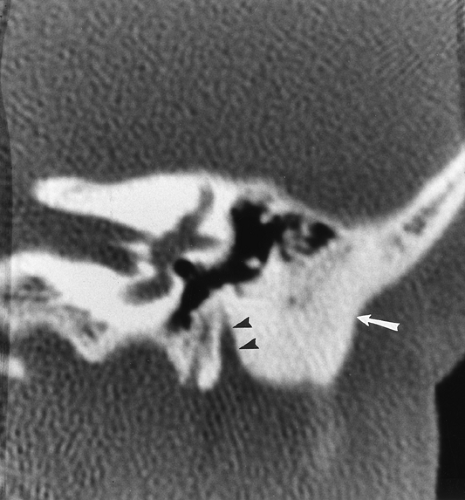

Some normal anatomic variants need to be considered when evaluating the temporal bone with CT. The dehiscent

(anomalous) jugular bulb (Fig. 38-4) is the most common major variant. The aberrant internal carotid artery is much less common but potentially has more significance. Both of these variants may be clinically mistaken for glomus tumors. It is important for the radiologist to make the correct diagnosis.

(anomalous) jugular bulb (Fig. 38-4) is the most common major variant. The aberrant internal carotid artery is much less common but potentially has more significance. Both of these variants may be clinically mistaken for glomus tumors. It is important for the radiologist to make the correct diagnosis.

Although congenital abnormalities of the temporal bone are relatively uncommon, some are correctable, and precise definition is therefore important before surgery is considered. HRCT is very important for proper management of patients with congenital defects.

These malformations consist of two groups, which are separable on the basis of embryologic derivation. The first group comprises developmental defects of the external and middle ear, both of which are derived from the first and second branchial arches and clefts. This group includes those abnormalities that produce conduction defects that may be surgically correctable. The second group, which consists of structures that originate from the auditory vesicle, includes all of the inner ear anomalies. These lesions are associated with sensorineural deafness and, although not surgically correctable, may be helped by devices such as cochlear implants.1,4,5

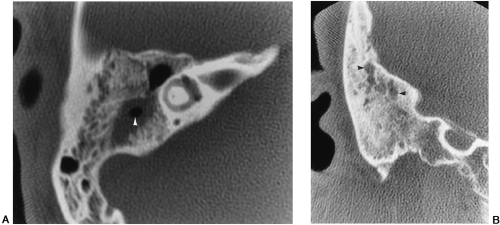

Those defects that are related to branchial arch development include deformity of the auricle, partial or complete atresia of the external auditory canal, and ossicular abnormalities (Fig. 38-5). Any of these may be accompanied by anterior malposition of the facial nerve, the location of which must be identified preoperatively.

Inner ear anomalies vary from abnormalities involving solely the semicircular canals to complete aplasia of the otic capsule. A rare but well known abnormality, the Mondini defect, is caused by partial or total absence of the cochlear turns (Fig. 38-6).1,4,5

INFLAMMATION

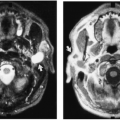

Most of the inflammatory changes that occur in the temporal bone result from uncontrolled external or middle ear infections. The most common etiologic organisms are the β-hemolytic streptococcus and pneumococcus, except in children younger than 5 years of age, who are frequently infected by Hemophilus influenzae. Acute mastoiditis is a frequent complication of otitis media and is commonly seen on CT scans (Fig. 38-7A). Acute petrositis, which may develop from the extension of mastoid infection into petrous air cells, also has become less common.

Subacute and chronic mastoiditis usually are caused by recurrent otitis media. So long as the disease remains confined to the mucosa and air space, it is potentially reversible with treatment. Once it reaches a stage termed coalescent mastoiditis, the disease cannot be completely reversed (Fig. 38-7B). This stage signifies the conversion from mucosal disease to bone disease. The thickened infected mucous membrane and mucopurulent secretions erode the mastoid bony septa, eventually leading to bony sclerosis.1,4,5

Tuberculosis and syphilis may also produce inflammatory changes in the temporal bone, but these are rare. Another unusual but potentially lethal inflammation is produced by

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This organism, typically found in elderly diabetic patients, often causes an aggressive infection of the external and middle ear. The advanced osseous destruction of the temporal bone that occurs has led to the designation of this entity as malignant external otitis (Fig. 38-8).1

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This organism, typically found in elderly diabetic patients, often causes an aggressive infection of the external and middle ear. The advanced osseous destruction of the temporal bone that occurs has led to the designation of this entity as malignant external otitis (Fig. 38-8).1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree