Chapter 23 Thyroid cancer

Anatomy

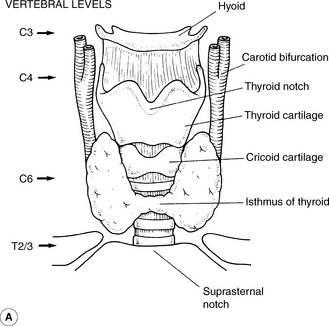

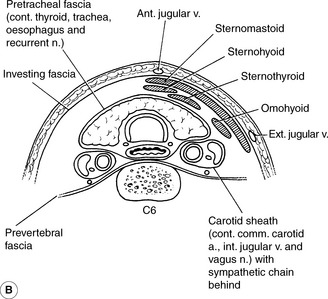

The thyroid gland is situated in the anterior part of the neck just above the clavicle and sternum (Figure 23.1). The gland consists of a right and left lobe joined by an isthmus which crosses the trachea at the second and third cartilaginous rings. The average weight of the thyroid gland is 20 g. The parathyroid glands lie on the posterior surface of both thyroid lobes and the recurrent laryngeal nerves are in a cleft between the trachea and the oesophagus. Lymphatic drainage from the thyroid can be to nodes superior to the thyroid gland, lateral to the gland and to the paratracheal region.

Presentation, diagnosis and patient pathway

Staging is performed using the TNM system which is summarized in Table 23.1. All anaplastic carcinomas are considered T4 tumours.

| T1 | Tumour <=2 cm, intrathyroidal |

| T1a | <=1 cm |

| T1b | 1-2 cm |

| T2 | Tumour >2-4 cm, intrathyroidal |

| T3 | Tumour >4 cm on with minimal extra-thyroid extension |

| T4 | Tumour extending beyond the thyroid capsule |

| T4a | Subcutaneous tissue, larynx, trachea, R L Nerve. Oesophagus |

| T4b | Prevertebral fascia, mediatinal vessels, carotid artery |

| N0 | No regional lymph node involvement |

| N1 | Regional lymph node involvement |

| N1a | Level VI |

| N1b | Other regional |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis present |

This system defines high-risk patients as:

Low-risk patients are described as:

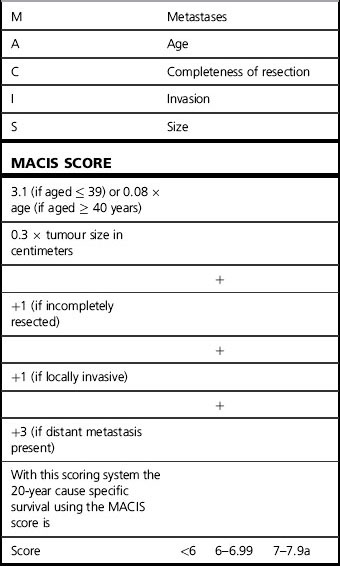

Another system which gives prognostic information is the MACIS scoring scheme developed at the Mayo Clinic (Table 23.2).

Differentiated thyroid cancer

Surgery

Nomenclature currently used for diagnostic categorization is the Thy 1, Thy 2 etc. system, and can be found in the ‘Guidelines for the management of Thyroid Cancer in Adults’ published by the British Thyroid Association and the Royal College of Physicians of London. This system can be summarized as shown in Table 23.3. Further refinements of this system into Thy3a (atypia) and Thy3f (Follicular lesion)have been proposed recently.

Table 23.3 British Thyroid Association coding system

| Thy1 | Non-diagnostic; FNAC needs repeating |

| Thy2 | Non-neoplastic; two diagnostic tests with benign results with 3–6 months apart are needed to exclude malignancy |

| Thy3 | All follicular lesions; lobectomy required with completion thyroidectomy if malignant histology |