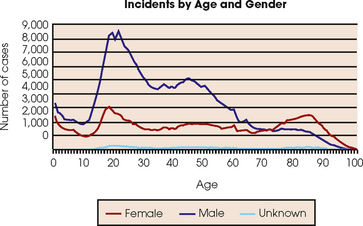

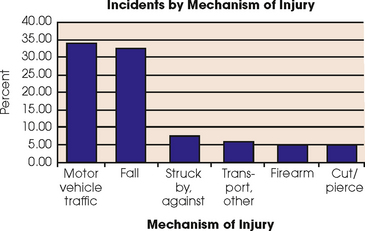

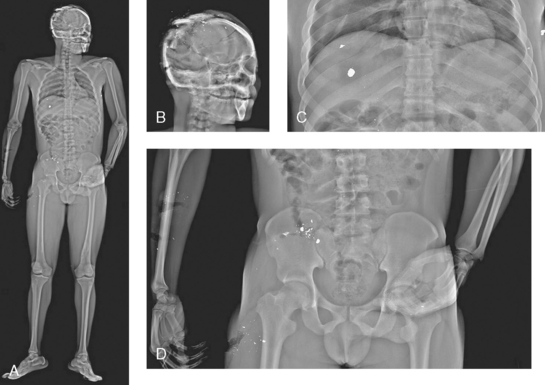

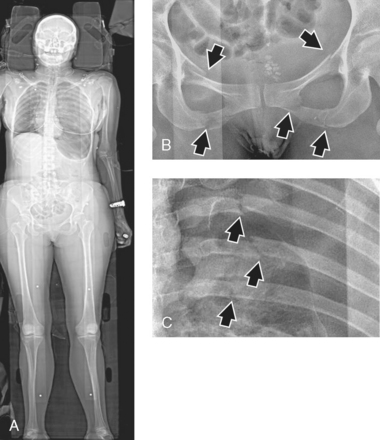

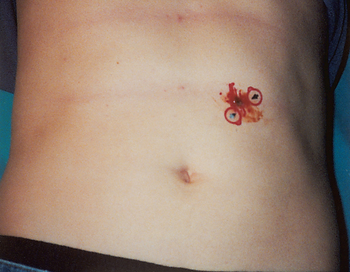

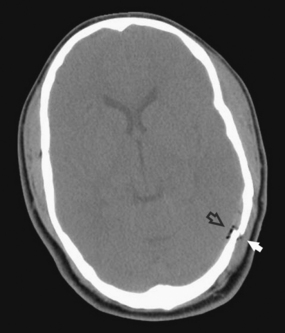

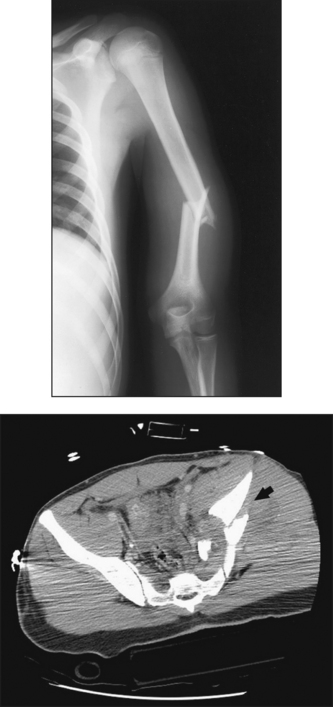

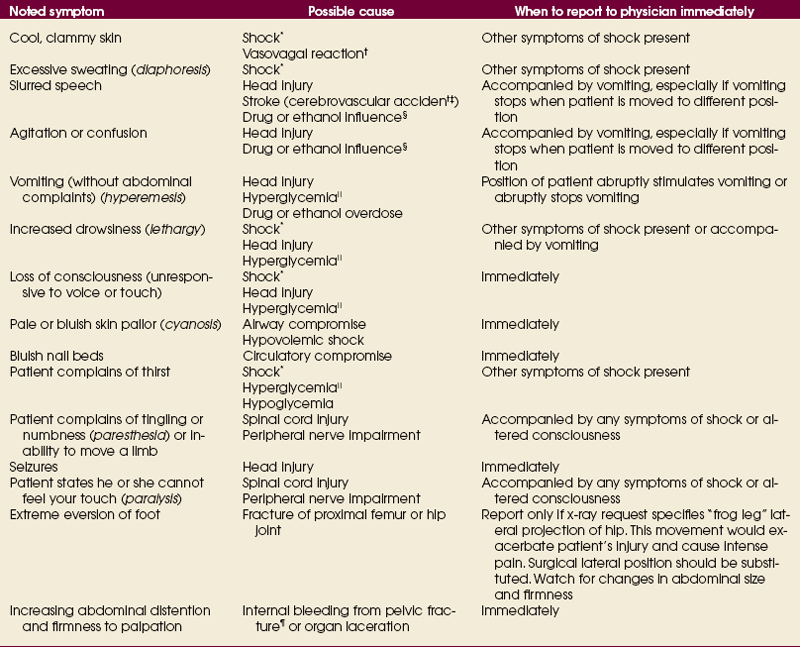

13 Trauma-related injuries affect persons in all age ranges. Fig. 13-1 shows trauma incidence by age and gender, as reported by the American College of Surgeons’ National Trauma Database (NTDB) 2008 annual report. The database contains greater than 3 million records from more than 400 hospitals and has received information from across the United States. These data show that trauma patients most commonly are male, ranging in age from teenagers to early adults. Fig. 13-2 shows the distribution of trauma injuries by cause, with the most common being motor vehicle accidents (MVAs). Firearms rank next to last as a cause of injury; however, the 2008 NTDB report also shows that firearms have the highest fatality rate The data show the most common trauma patients and mechanisms of injury, but the imaging professional who chooses to work in the ED must be prepared to care for patients from every age range exhibiting a vast array of injuries. Time is a crucial element in the care of a trauma patient. To minimize the time needed to acquire diagnostic x-ray images, many EDs have dedicated radiographic equipment located in the department or immediately adjacent to the department. Trauma radiographs must be taken with minimal patient movement, requiring more maneuvering of the tube and image receptor (IR). Specialized trauma radiographic systems are available and are designed to provide greater flexibility in x-ray tube and IR maneuverability (Fig. 13-3). These specialized systems help to minimize movement of the injured patient while performing imaging procedures. Additionally, some EDs are equipped with specialized beds or stretchers that have a movable tray to hold the IR. This type of stretcher allows the use of a mobile radiographic unit and eliminates the requirement and risk of transferring an injured patient to the radiographic table. Mobile fluoroscopy units, usually referred to as C-arms because of their shape, are becoming more commonplace in EDs. C-arms are used for fracture reduction procedures, foreign body localization in limbs, and reduction of joint dislocations (Fig. 13-4). An emerging imaging technology has the potential to have a significant effect on trauma radiography. The Statscan (Lodox Systems [Pty], Ltd.) is a relatively new imaging device that produces full-body imaging scans in approximately 13 seconds without moving the patient (Figs. 13-5 to 13-7). There are at present approximately 17 of these systems worldwide. At a cost of approximately $450,000, this technology is an expensive addition to trauma imaging. Radiographic exposure factor compensation may be required when making exposures through immobilization devices such as a spine board or backboard. Most trauma patients arrive at the hospital with some type of immobilization device (Fig. 13-8). Pathologic changes should also be considered when setting technical factors. Internal bleeding in the abdominal cavity would absorb a greater amount of radiation than a bowel obstruction. The primary challenge of the trauma radiographer is to obtain a high-quality, diagnostic image on the first attempt when the patient is unable to move into the desired position. Many methods are available to adapt a routine projection and obtain the desired image of the anatomic part. To minimize the risk of exacerbating the patient’s condition, the x-ray tube and IR should be positioned, rather than the patient or the part. The stretcher can be positioned adjacent to the vertical Bucky or upright table as the patient’s condition allows (Fig. 13-9). This location enables accurate positioning with minimal patient movement for cross-table lateral images (dorsal decubitus positions) on numerous parts of the body. Additionally, the grid in the table or vertical Bucky is usually a higher ratio than that used for mobile radiography, so image contrast is improved. Another technique to increase efficiency, while minimizing patient movement, is to take all of the AP projections of the requested examinations moving superiorly to inferiorly. All of the lateral projections of the requested examinations are then performed moving inferiorly to superiorly. This method moves the x-ray tube in the most expeditious manner. When taking radiographs to localize a penetrating foreign object, such as metal or glass fragments or bullets, the entrance and exit wounds should be marked with a radiopaque marker that is visible on all projections (Fig. 13-10). Two exposures at right angles to each other show the depth and the path of the projectile. • Perform quality diagnostic imaging procedures as requested • Practice ethical radiation protection for self, patient, and other personnel • Close collimation to the anatomy of interest to reduce scatter • Gonadal shielding for patients of childbearing age (when doing so does not interfere with the anatomy of interest) • Lead aprons for all personnel that remain in the room during the procedure • Exposure factors that minimize patient dose and scattered radiation • Announcement of impending exposure to allow unnecessary personnel to exit the room The familiar ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation) of basic life support techniques must be constantly assessed during the radiographic procedures. Visual inspection and verbal questioning enable the radiographer to determine whether the status of the patient changes during the procedure. Table 13-1 provides a guide for the trauma radiographer regarding changes in status that should be reported immediately to the attending physician. Table 13-1 includes only the common injuries in which the radiographer may be the only health care professional with the patient during the imaging procedure. Patients with multiple trauma injuries and patients in respiratory or cardiac arrest usually are imaged with a mobile radiographic unit while ED personnel are present in the room. In these situations, the primary responsibility of the trauma radiographer is to produce quality images in an efficient manner while practicing ethical radiation protection measures. TABLE 13-1 Guide for reporting patient status change *Hypovolemic or hemorrhagic shock is a medical condition in which there are abnormally low levels of blood plasma in the body, such that the body cannot properly maintain blood pressure, cardiac output of blood, and normal amounts of fluid in the tissues. It is the most common type of shock in trauma patients. Symptoms include diaphoresis, cool and clammy skin, decrease in venous pressure, decrease in urine output, thirst, and altered state of consciousness. †Vasovagal reaction is also called a vasovagal attack, situational syncope, and vasovagal syncope. It is a reflex of the involuntary nervous system or a normal physiologic response to emotional stress. Patients may complain of nausea, feeling flushed (warm), and feeling lightheaded. They may appear pale before they lose consciousness for several seconds. ‡Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is commonly called a stroke and may be caused by thrombosis, embolism, or hemorrhage in the vessels of the brain. §Drugs or alcohol. Patients under the influence of drugs or alcohol or both commonly present in the ED. In this situation, the usual symptoms of shock and head injury are unreliable. Be on guard for aggressive physical behaviors and abusive language. ||Hyperglycemia is also known as diabetic ketoacidosis. The cause is increased blood glucose levels. The patient may exhibit any combination of symptoms noted and has fruity-smelling breath. ¶Pelvic fractures have a high mortality rate (mortality with open fractures may be 50%). Hemorrhage and shock are often associated with this type of injury. 1. Speed: Trauma radiographers must produce quality images in the shortest amount of time. Rapidity in performing a diagnostic examination is crucial to saving the patient’s life. Many practical methods that increase examination efficiency without sacrificing image quality are introduced in this chapter. 2. Accuracy: Trauma radiographers must provide accurate images with a minimal amount of distortion and the maximum amount of recorded detail. Alignment of the central ray, the part, and the IR also applies in trauma radiography. Using the shortest exposure time minimizes the possibility of imaging involuntary and uncontrollable patient motion. 3. Quality: Quality does not have to be sacrificed to produce an image quickly. The patient’s condition should not be used as an excuse for careless positioning and accepting less than high-quality images. 4. Positioning: Careful precautions must be taken to ensure that performance of the imaging procedure does not exacerbate the patient’s injuries. The “golden rule” of two projections at right angles from one another still applies. As often as possible, the radiographer should position the tube and the IR, rather than the patient, to obtain the desired projections. 5. Practice standard precautions: Exposure to blood and body fluids should be expected in trauma radiography. The radiographer should wear gloves, mask, eye shields, and gown when appropriate. IR and sponges should be placed in nonporous plastic to protect them from body fluids. Hand hygiene should be performed frequently, especially between patients. All equipment and accessory devices should be kept clean and ready for use. 6. Immobilization: The radiographer should never remove any immobilization device without physician’s orders. The radiographer should provide proper immobilization and support to increase patient comfort and to minimize risk of motion. 7. Anticipation: Anticipating required special projections or diagnostic procedures for certain injuries makes the radiographer a vital part of the ED team. Patients requiring surgery generally require an x-ray of the chest. In facilities where CT is not readily available for emergency patients, fractures of the pelvis may require a cystogram to determine the status of the urinary bladder. The radiographer should know which procedures are often referred to CT first or for additional images. Being prepared for and understanding the necessity of these additional procedures and images instills confidence in, and creates an appreciation for, the role of the radiographer in the emergency setting. 8. Attention to detail: The radiographer should never leave a trauma patient (or any patient) unattended during imaging procedures. The patient’s condition may change at any time, and it is the radiographer’s responsibility to note these changes and report them immediately to the attending physician. If the radiographer cannot process images while maintaining eye contact with the patient, he or she should call for help. Someone must be with the injured patient at all times. 9. Attention to department protocol and scope of practice: The radiographer should know department protocols and practice only within his or her own competence and abilities. The scope of practice for radiographers varies from state to state and from country to country. The radiographer should study and understand the scope of his or her role in the emergency setting. The radiographer should not provide or offer a patient anything by mouth. The radiographer should always ask the attending physician before giving the patient anything to eat or drink, no matter how persistent the patient may be. 10. Professionalism: Ethical conduct and professionalism in all situations and with every person is a requirement of all health care professionals, but the conditions encountered in the ED can be particularly complicated. The radiographer should adhere to the Code of Ethics for Radiologic Technologists (see Chapter 1) and the Radiography Practice Standards. The radiographer should be aware of the people present or nearby at all times when discussing a patient’s care. The ED radiographer is exposed to myriad tragic conditions. Emotional reactions are common and expected but must be controlled until the emergency care of the patient is complete. The projections included in this chapter result from a telephone survey of Level I trauma centers. The results indicated that the common radiographic projections ordered for initial trauma surveys are as follows1: • Cervical spine, dorsal decubitus position (cross-table lateral) • Abdomen, AP (kidneys, ureter, and bladder [KUB] and acute abdominal series) • Cervical spine, AP and obliques Skull radiographs did not rank as one of the most common imaging procedures performed in the ED of Level I trauma centers. Most Level I trauma centers have replaced conventional trauma skull radiographs (e.g., AP, lateral, Towne, reverse Waters) with CT scan of the head (Fig. 13-11). Research articles continue to delineate the advantages of CT over radiography, and the results indicate that certain types of head trauma should be referred to CT first. Smaller facilities may not have CT readily available, however. Trauma skull positioning remains valuable knowledge for the radiographer.

TRAUMA RADIOGRAPHY

Trauma Statistics

Preliminary Considerations

EXPOSURE FACTORS

POSITIONING OF THE PATIENT

Radiographer’s Role as Part of the Trauma Team

RADIATION PROTECTION

PATIENT CARE

Best Practices in Trauma Radiography

Radiographic Procedures in Trauma

TRAUMA RADIOGRAPHY