Fig. 32.1

Reversible pathogenesis of osteonecrosis

Table 32.1

Screening tests for thrombophilia, hypofibrinolysis, and impairment of nitric oxide production

Thrombophilia |

PCR studies |

G1691A Factor V Leiden |

G20210A prothrombin |

C677T/A1298C MTHFR |

Serologic studies |

Factor VIII |

Factor XI |

Antigenic protein C |

Antigenic protein S (total and free) |

Antigenic antithrombin III |

Homocysteine |

Anticardiolipin antibody IgG |

Anticardiolipin antibody IgM |

Beta-2-glycoprotein |

Lupus anticoagulant |

Hypofibrinolysis |

PCR studies |

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene 4G4G mutation |

Serologic studies |

Lipoprotein (a) |

Plasminogen activator inhibitor activity |

Genetic predisposition due to nitric oxide production impairment |

PCR studies |

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene polymorphisms (T-786C polymorphism, 4a intron 4 polymorphism) |

The pathogenesis of ON probably reflects a “multiple etiology” [23–29] model, Fig. 32.1. We, and then others, have postulated a sequence for the development of ON. Osseous venous outflow obstruction is caused by venous thrombosis due to thrombophilia-hypofibrinolysis [1, 3–5, 7, 17], leading to increased intraosseous venous pressure, reduced arterial flow, ischemia, and bone death [10, 11, 13, 23–26, 30–33], Fig. 32.1. Experimental models of ON [23–26] confirm venous occlusion as a primary event. We have speculated that anticoagulation facilitates lysis of intraosseous thrombi, reducing elevated intraosseous venous pressure, improving arterial flow, reversing hypoxia, stopping bone death, and allowing bone healing (Fig. 32.1) [17].

In the current report, our focus is on intact functional hip survival 4.2–7 years after a 3-month course of enoxaparin. We have previously reported [17] a prospective pilot study of 16 primary ON patients (25 hips) with thrombophilia-hypofibrinolysis treated with enoxaparin for the same duration as used in deep venous thrombosis of leg veins [34] (60 mg/day, 3 months). This treatment stopped the progression of ischemic Ficat [35] stages I or II primary ON over ≥ 108 week follow-up. Survival of 19 of 25 hips (76 %), based on intent to treat, compared favorably with untreated historical controls (~20 % 2 year survival) [36–38]. We concluded that enoxaparin often prevents progression of primary hip ON in patients with thrombophilia-hypofibrinolysis, decreasing THR [17]. We concluded [17] that seeking a nonoperative anticoagulant route for treatment of Ficat stage I or II primary ON holds considerable promise in preserving the femoral head. However, in thrombophilic-hypofibrinolytic patients with osteonecrosis secondary to corticosteroids, alcohol, etc., 3 months therapy with enoxaparin does not stop the progression of Ficat stages I or II osteonecrosis, and these patients have the same hip failure rate as untreated patients [17], requiring THR.

We are now reporting prospectively on outcomes in 20 patients (30 hips), over 4.2–7-year follow-up after initial enoxaparin treatment (60 mg/day for 3 months) [17] in preventing progression of stages I and II primary ON of the hip(s) associated with thrombophilia and/or hypofibrinolysis. We also assessed 36–40-month follow-up success of enoxaparin treatment (1.5 mg/kg/day for 3 months) in 7 patients (11 knees) in preventing progression of primary ON of the knee.

32.2 Prospective Study of 4- to 7-Year Outcomes in 20 Patients (30 Hips) and in 7 Patients (11 Knees) After Initial Treatment with Enoxaparin

The Cincinnati studies described in this chapter were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the Institutional Review Board at the Jewish Hospital; signed informed consent was obtained.

32.2.1 Hip Outcomes

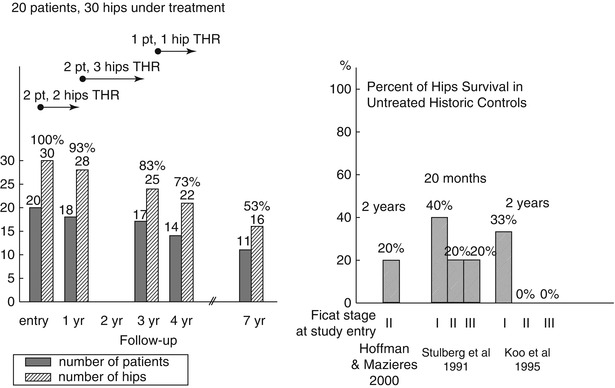

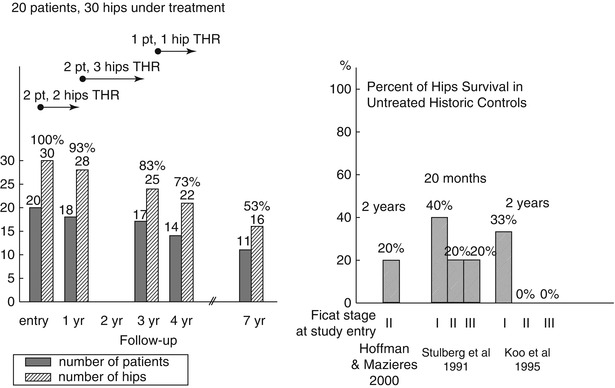

Based on intent to treat, at 4-year follow-up, 22 of the original 30 hips (73 %) remained unchanged (Ficat stages I or II), as did 16 of 30 hips (53 %) at 7 years (Fig. 32.2). Those hips showing no change from Ficat stages I or II also remained asymptomatic and fully functional.

Fig. 32.2

Hip survival over 7-year prospective follow-up in 20 patients (30 hips) with primary ON (initial Ficat stage I or II), all receiving an initial 3-month therapy with enoxaparin. Hip survival in untreated historical controls and 20-month and 2-year follow-up

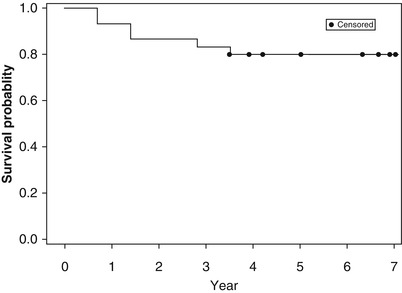

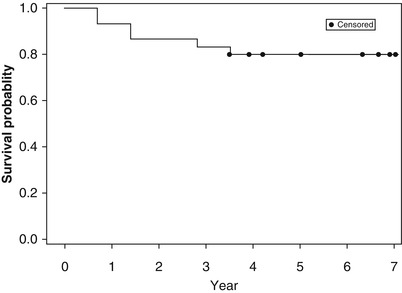

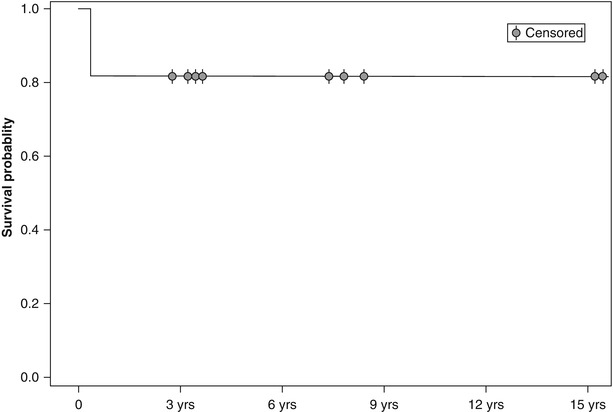

The Kaplan-Meier survival estimate (Fig. 32.3) is defined as “products of loss.” The Kaplan-Meier survival estimate distinguishes between end of follow-up without hip failure (censored) and real hip failure requiring THR (uncensored). At the beginning of the study, the survival function is 1. At each time point, if there are any real failures, then the survival function will be reduced by the number of failures divided by the number of observations left just before this time point. The Kaplan-Meier hip survival (Ficat I or II) probability was 80 % at 7-year follow-up, Fig. 32.3.

Fig. 32.3

Kaplan-Meier plot of hip survival, over 7-year prospective follow-up, starting with 30 hips in 20 patients with primary ON, all receiving an initial 3-month therapy with enoxaparin, initial Ficat stage I or II

Two patients, both heterozygous for the Factor V Leiden mutation, required chronic anticoagulation, one with enoxaparin followed by Xarelto (6 years) and one with Warfarin (13 years), because of ≥ 2 thrombotic events. These two patients had no change from pretreatment Ficat I or II ON of ≥ 1 hip at 6 and 13 years follow-up, respectively.

Compared with untreated historical controls (approximately 20 % 2-year hip survival, Fig. 32.2), 4-year survival of 22 of 30 (73 %) hips based on intent to treat, and 80 % survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis (Fig. 32.3), suggests that the original 12-week enoxaparin thromboprophylaxis produced lasting benefit in primary ON in patients with heritable thrombophilia-hypofibrinolysis.

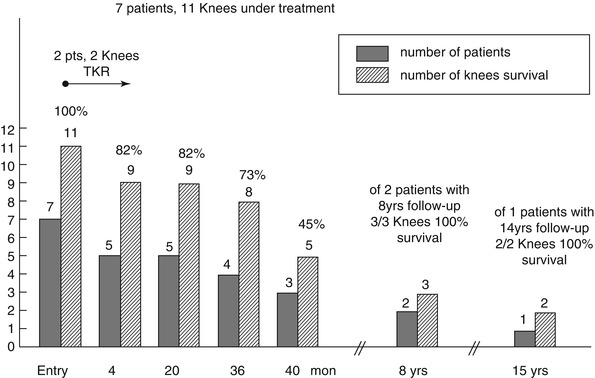

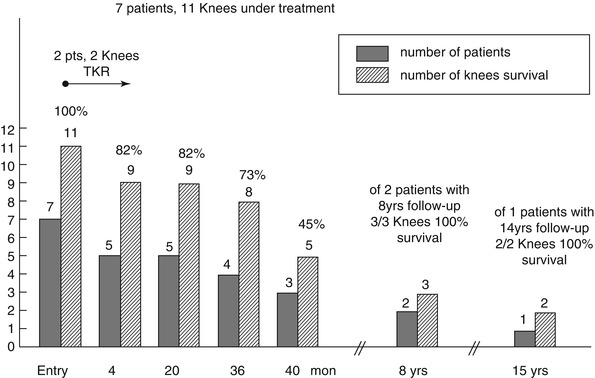

32.2.2 Knee Outcomes

The extent of knee ON in 7 patients (11 knees) was prospectively determined by X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). All 7 patients received enoxaparin (1.5 mg/kg/day for 3 months).

At 4 months, 2 patients (2 knees) had total knee replacement because of joint collapse, Fig. 32.4. At 20 months, 5 patients (9 knees, 82 %) had no progression by X-ray and MRI. At 36 months, 8 of the 11 knees survived (73 %) with no progression by X-ray and MRI, Fig. 32.4. At 40 months, 5 of the 11 knees survived (45 %), Fig. 32.4. Two patients (3 knees) had ≥ 8 years of follow-up, with 100 % knee survival. In 1 patient (2 knees) with 15 years follow-up, there was no progression by X-ray and MRI, with 100 % knee survival (Fig. 32.4).

Fig. 32.4

Knee survival over prospective 15-year follow-up in 7 patients (11 knees) with primary ON, all receiving an initial 3-month therapy with enoxaparin

In the five patients (nine knees) still undergoing follow-up, their knees were predominantly pain free and functional.

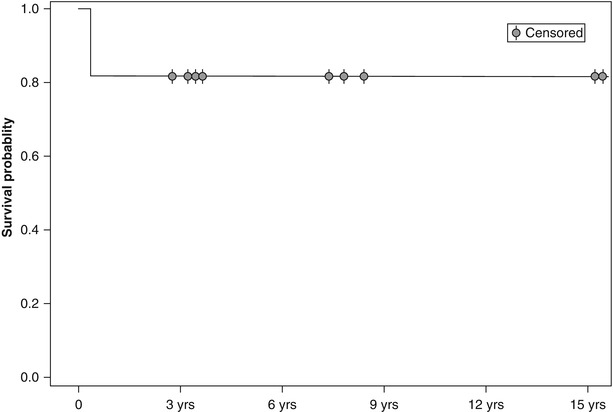

The Kaplan-Meier knee survival-probability was 82 % up to 15 year follow-up, Fig. 32.5.

Fig. 32.5

Kaplan-Meier plot of knee survival over 15-year prospective follow-up, starting with 11 knees in 7 patients with primary ON, all receiving an initial 3-month therapy with enoxaparin

Satku et al. [39] have prospectively studied 21 untreated adults with ON of the knee for at least 3 years and described three distinct patterns of outcome: (1) acute extensive collapse within 3 months of onset in 2 patients, (2) rapid progression to varying degrees of osteoarthritis in 12 knees (8 within 1 year, all 12 within 2 years), and (3) complete resolution in 4 knees. The 2 patients with acute extensive collapse and 3 who had rapid progression to severe osteoarthritis required total knee arthroplasty.

32.3 Discussion

Previous studies have suggested that all strategies for treatment of ON have certain limitations [36–38, 40–46], are difficult to develop [47], do not reverse ON’s primary pathologies [48], and may not halt progression to segmental collapse [48]. Our goal is preservation of the femoral head [47] and the knee by treating ON caused by thrombophilia-hypofibrinolysis with enoxaparin, reversing a primary (coagulation) pathology of ON [48]. In our current study, compared with untreated historical controls, approximately 20 % 2-year hip survival (Fig. 32.2), 4-year survival of 22 of 30 (73 %) of hips based on intent to treat (Fig. 32.2), and 80 % survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis (Fig. 32.3), suggests that the original 12 week enoxaparin therapy produced lasting benefit in primary ON in patients with heritable thrombophilia-hypofibrinolysis. Enoxaparin may prevent progression of primary hip ON [17], allowing many patients to avoid THR. The 6- and 13-year survival of 3 hips in 2 patients heterozygous for the V Leiden mutation chronically anticoagulated with warfarin or enoxaparin and then Xarelto suggests that chronic anticoagulation might be very useful in stopping progression of primary hip ON. Except these 2 patients, however, we have not studied repeated courses of enoxaparin treatment or constant anticoagulation due to FDA restrictions when we began our initial study [17]. However, we suspect that the results would likely to be improved as new occurrences of femoral head venous thrombosis are probably likely after cessation of the 13-week initial course of enoxaparin, leading to delayed failure of the initial treatment regimen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree