Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of the Joints

Benign Lesions

Synovial (Osteo)Chondromatosis

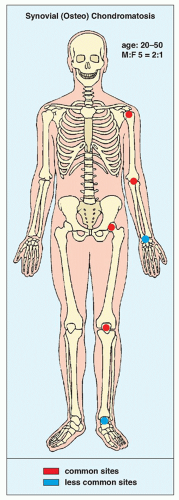

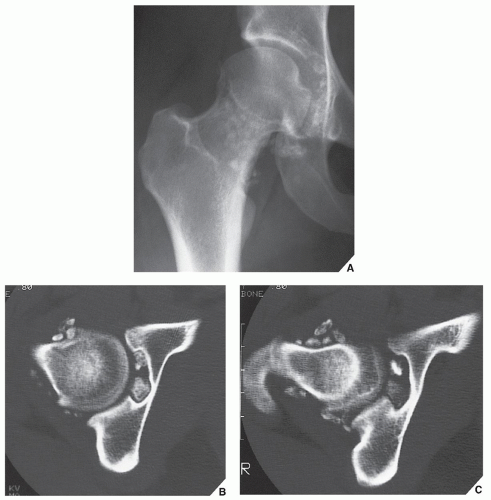

Synovial (osteo)chondromatosis (also known as synovial chondromatosis or synovial chondrometaplasia) is an uncommon benign disorder marked by the metaplastic proliferation of multiple cartilaginous nodules in the synovial membrane of the joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths. It is almost invariably monoarticular; rarely, multiple joints may be affected. The disorder is twice as common in men as in women and is usually discovered in the third to fifth decade. The knee is a preferential site of involvement, with the hip, shoulder, and elbow accounting for most of the remaining cases (Fig. 23.1). Patients usually report pain and swelling. Joint effusion, tenderness, limited motion in the joint, and a soft-tissue mass are common clinical findings.

Three phases of articular disease have been identified: an initial phase, characterized by metaplastic formation of cartilaginous nodules in the synovium; a transitional phase, characterized by detachment of those nodules and formation of free intraarticular bodies; and an inactive phase, in which synovial proliferation has resolved but loose bodies remain in the joint, usually with variable amounts of joint fluid.

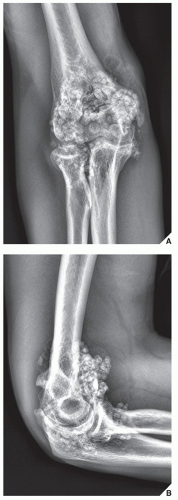

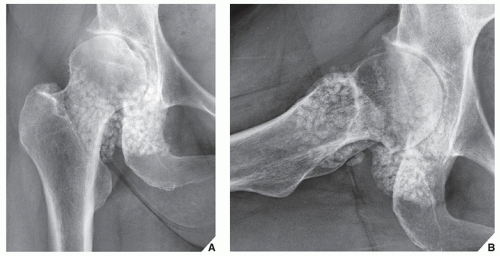

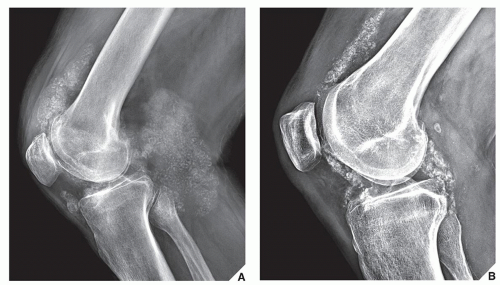

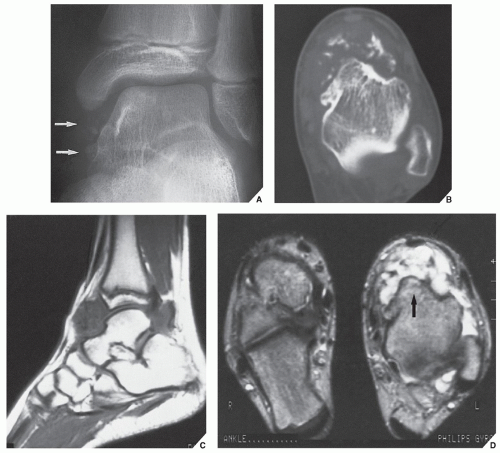

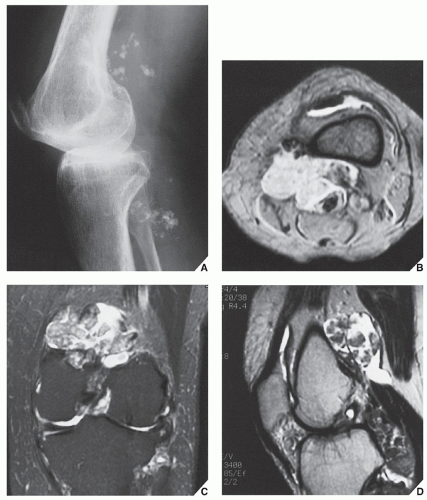

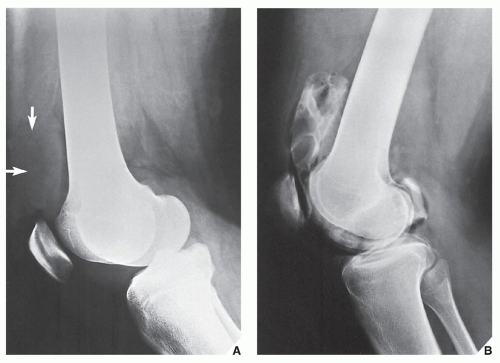

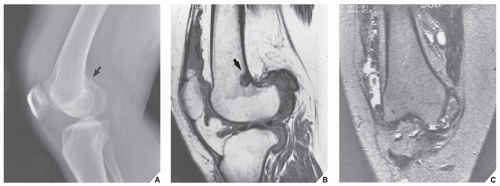

The imaging findings depend on the degree of calcification within the cartilaginous bodies, ranging from mere joint effusion to visualization of many radiopaque joint bodies, usually small and uniform in size (Figs. 23.2, 23.3, 23.4). The best proof that the bodies are indeed intraarticular is achieved by arthrography or computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 23.5). These modalities can visualize even noncalcified bodies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be helpful, although MRI appearance is variable and depends on the relative preponderance of synovial proliferation, loose bodies formation, and extent of calcification or ossification. Unmineralized hyperplastic synovial masses exhibit high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, whereas calcifications can be seen as signal void against the high-signal intensity fluid (Figs. 23.6 and 23.7). In addition to revealing loose bodies in the joint, CT and MRI may demonstrate bony erosion.

By microscopy, many cartilaginous nodules are observed as they form beneath the thin layer of cells that line the surface of the synovial membrane. These nodules are highly cellular, and the cells themselves may exhibit a moderate pleomorphism, with occasional plump and double nuclei. The cartilaginous nodules, which often are undergoing calcification and endochondral ossification, may detach and become loose bodies. The loose bodies continue to be viable and may increase in size as they receive nourishment from the synovial fluid.

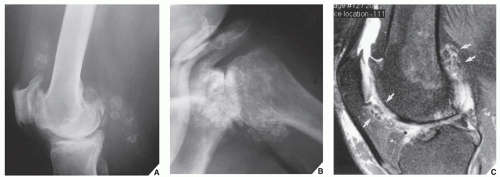

Differential Diagnosis

Synovial (osteo)chondromatosis should be differentiated from the secondary osteochondromatosis caused by osteoarthritis, particularly in the knee and hip joints, and from synovial chondrosarcoma, either primary (arising de novo from the synovial membrane) or secondary (caused by malignant transformation). Distinguishing primary from secondary osteochondromatosis usually presents no problems. In the latter condition, there is invariably radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis with all of its typical features, such as narrowing of the radiographic joint space, subchondral sclerosis, and, occasionally, periarticular cysts or cyst-like lesions (Fig. 23.8). The loose bodies are fewer, larger, and invariably of different sizes. Conversely, in primary synovial (osteo)chondromatosis, the joint is not affected by any degenerative changes. In some cases, however, the bone may show erosions secondary to pressure of the calcified bodies on the outer aspects of the cortex. The intraarticular bodies are numerous, small, and usually of uniform size (see Figs. 23.2, 23.3, 23.4).

It is more difficult to distinguish synovial chondromatosis from synovial chondrosarcoma. The clinical and radiographic features have not been useful in this differentiation and are equally ineffective in distinguishing a secondary malignant lesion arising in synovial (osteo)chondromatosis. In addition, both entities tend to have a protracted clinical course, and local recurrence is common after synovectomy for synovial chondromatosis or local resection of synovial chondrosarcoma. The presence of frank bone destruction rather than merely erosions, and the association of a soft-tissue mass, should always raise a concern for malignancy (see Fig. 23.22). Although extension beyond the joint capsule should heighten the suspicion of malignancy, some cases of synovial chondromatosis have been reported to have extraarticular extension.

The other conditions that can radiologically mimic synovial chondromatosis include pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), synovial hemangioma, and lipoma arborescens. In PVNS (discussed in detail later in this chapter), the filling defects in the joint are more confluent and less distinct. MRI may show foci of decreased intensity of the synovium in all sequences because of the paramagnetic effects of deposition of hemosiderin (see Figs. 23.12 and 23.13). Synovial hemangioma usually presents as a single soft-tissue mass. On MRI, T1-weighted images show that the lesion is either isointense or slightly higher (brighter) in signal intensity than surrounding muscles but much lower in intensity than subcutaneous fat. On T2-weighted images, the mass is invariably much brighter than fat (see Figs. 23.15 and 23.16). Phleboliths and fibrofatty septa in the mass are common findings that show low-signal characteristics. Lipoma arborescens is a villous lipomatous proliferation of the synovial membrane. This rare condition usually affects the knee joint but has occasionally been reported in other joints, including

the wrist and ankle. The disease has been variously reported to have a developmental, traumatic, inflammatory, or neoplastic origin, but its true cause is still unknown. The clinical findings include slowly increasing but painless synovial thickening as well as joint effusion with sporadic exacerbation. Imaging studies reveal a joint effusion occasionally accompanied by various degrees of osteoarthritis (see Fig. 23.17). Histologic examination demonstrates complete replacement of the subsynovial tissue by mature fat cells and the formation of proliferative villous projections (see in the following text).

the wrist and ankle. The disease has been variously reported to have a developmental, traumatic, inflammatory, or neoplastic origin, but its true cause is still unknown. The clinical findings include slowly increasing but painless synovial thickening as well as joint effusion with sporadic exacerbation. Imaging studies reveal a joint effusion occasionally accompanied by various degrees of osteoarthritis (see Fig. 23.17). Histologic examination demonstrates complete replacement of the subsynovial tissue by mature fat cells and the formation of proliferative villous projections (see in the following text).

Treatment of synovial chondromatosis usually consists of removal of the intraarticular bodies and synovectomy, but local recurrence is not uncommon.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

PVNS is a locally destructive fibrohistiocytic proliferation, characterized by many villous and nodular synovial protrusions, which affects joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths. PVNS was first described by Jaffe, Lichtenstein, and Sutro in 1941, who used this name to identify the lesion because of its yellow-brown, villous, and nodular appearance. The yellow-brown pigmentation is caused by excessive deposits of lipid and hemosiderin. This condition can be diffuse or localized. When the entire synovium of the joint is affected, and when there is a major villous component, the condition is referred to as diffuse PVNS. When a discrete intraarticular mass is present, the condition is called localized PVNS. When the process affects the tendon sheaths, it is called localized giant cell tumor of the tendon sheaths. The diffuse form usually occurs in the knee, hip, elbow, or wrist and accounts for 23% of cases. The localized nodular form is often regarded as a separate entity. It consists of a single polypoid mass attached to the synovium. Nodular tenosynovitis is most often seen in the fingers and is the second most common soft-tissue tumor of the hand, exceeded only by the ganglion. In the new (2002) revised classification of soft-tissue tumors, the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies localized intraarticular and extraarticular lesions as giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, whereas diffuse intraarticular and extraarticular forms are categorized as diffuse-type giant cell tumor (keeping PVNS as a synonym).

Both the diffuse and the localized form of villonodular synovitis usually occur as a single lesion, mainly in young and middle-aged individuals of either sex. One of the most characteristic findings in PVNS is the ability of the hyperplastic synovium to invade the subchondral bone, producing cysts and erosions. Although the cause is unknown and is often controversial, some investigators have suggested an autoimmune pathogenesis. Trauma is also a suspected cause because similar effects have been produced experimentally in animals by repeated injections of blood into the knee joint. Some investigators have suggested a disturbance in lipid metabolism as a causative factor. It has also been postulated by Jaffe and colleagues that these lesions may represent an inflammatory response to an unknown agent. Stout and Lattes contended that they are true benign neoplasms. Although the latter theory was presumed to be supported

by pathologic studies indicating that the histiocytes present in PVNS may function as facultative fibroblasts and that foam cells may derive from histiocytes, thus relating PVNS to a benign neoplasm of fibrohistiocytic origin, these findings do not constitute definite proof that PVNS is a true neoplasm. They are rather indicative of a special form of a chronic proliferative inflammation process, as has already been postulated by Jaffe and colleagues.

by pathologic studies indicating that the histiocytes present in PVNS may function as facultative fibroblasts and that foam cells may derive from histiocytes, thus relating PVNS to a benign neoplasm of fibrohistiocytic origin, these findings do not constitute definite proof that PVNS is a true neoplasm. They are rather indicative of a special form of a chronic proliferative inflammation process, as has already been postulated by Jaffe and colleagues.

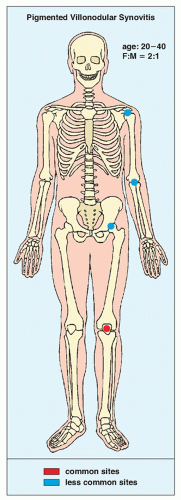

Clinically, PVNS is a slowly progressive process that manifests as mild pain and joint swelling with limitation of motion. Occasionally, increased skin temperature is noted over the affected joint. The knee joint is most commonly affected, and 66% of patients present with a bloody joint effusion. In fact, the presence of a serosanguineous synovial fluid in the absence of a history of recent trauma should strongly suggest the diagnosis of PVNS. The synovial fluid contains elevated levels of cholesterol, and fluid reaccumulates rapidly after aspiration. Other joints may be affected, including the hip, ankle, wrist, elbow, and shoulder. There is a 2:1 predilection for females. Patients range from 4 to 60 years of age, with a peak incidence in the third and fourth decades (Fig. 23.9). The duration of symptoms can range from 6 months to as long as 25 years.

FIGURE 23.9 Pigmented villonodular synovitis: sites of predilection, peak age range, and male-to-female ratio. |

Although a few “malignant” PVNS have been reported in the literature, this diagnosis is still debatable (see later). Recently, attention has been drawn to the extraarticular form of diffuse PVNS, also referred to as diffuse-type giant cell tumor. This condition is characterized by the presence of an infiltrate, and extraarticular mass with or without involvement of the adjacent joint. This presentation of PVNS creates a real diagnostic challenge for both radiologist and pathologist because its extraarticular location, invasion of the osseous structures, and more varied histologic infiltrative pattern may suggest malignancy.

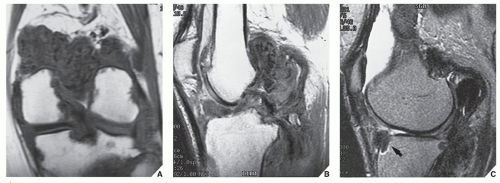

Radiography reveals a soft-tissue density in the affected joint, frequently interpreted as joint effusion. However, the density is greater than that of simple effusion, and it reflects not only a hemorrhagic fluid but also lobulated synovial masses (Fig. 23.10). A marginal, well-defined erosion of subchondral bone with a sclerotic margin may be present (incidence reported from 15% to 50%), usually on both sides of the affected articulation. Narrowing of the joint space has also been reported. In the hip, multiple cyst-like or erosive areas involving non-weight-bearing regions of the acetabulum, as well as the femoral head and neck, are characteristic. Calcifications are encountered only in exceptional cases.

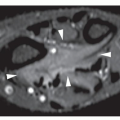

Arthrography reveals multiple lobulated masses with villous projections, which appear as filling defects in the contrast-filled suprapatellar bursa (Fig. 23.11). CT effectively demonstrates the extent of the disease. The increase in iron content of the synovial fluid results in high Hounsfield values, a feature that can help in the differential diagnosis. MRI is extremely useful in making a diagnosis, because on T2-weighted images, the intraarticular masses demonstrate a combination of high-signal intensity areas, representing fluid and congested synovium, interspersed with areas of intermediate to low signal intensity, secondary to random distribution of hemosiderin in the synovium (Fig. 23.12). In general, MRI shows a low signal on T1- and T2-weighted images because of hemosiderin deposition and thick fibrous tissue (Fig. 23.13). In addition, within the mass, signals

consistent with fat can be noted, which are caused by clumps of lipid-laden macrophages. Other MRI findings include hyperplastic synovium and occasionally bone erosions. Administration of gadolinium in the form of gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) leads to a notable increase in overall heterogeneity, which tends toward an overall increase in signal intensity of the capsule and septae. This enhancement of the synovium allows it to be differentiated from the fluid invariably present, which does not enhance. Apart from its diagnostic effectiveness, MRI is also useful in defining the extent of the disease.

consistent with fat can be noted, which are caused by clumps of lipid-laden macrophages. Other MRI findings include hyperplastic synovium and occasionally bone erosions. Administration of gadolinium in the form of gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) leads to a notable increase in overall heterogeneity, which tends toward an overall increase in signal intensity of the capsule and septae. This enhancement of the synovium allows it to be differentiated from the fluid invariably present, which does not enhance. Apart from its diagnostic effectiveness, MRI is also useful in defining the extent of the disease.

On histologic examination, PVNS reveals a tumor-like proliferation of the synovial tissue. A dense infiltration of mononuclear histiocytes is observed, accompanied by plasma cells, xanthoma cells, lymphocytes, and variable numbers of giant cells. Long-standing lesions show fibrosis and hyalinization.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common diagnostic possibilities include hemophilic arthropathy, synovial chondromatosis, synovial hemangioma, and synovial sarcoma. MRI is very

effective in distinguishing these entities because it can reveal hemosiderin deposition in PVNS. Although this feature may also be present in hemophilic arthropathy, detection of diffuse hemosiderin clumps, synovial irregularity and thickening, and distention of the synovial sac favors the diagnosis of PVNS. In addition, hemophilia, unlike PVNS, commonly affects multiple joints and is associated with growth disturbance at the articular ends of the affected bones. Synovial chondromatosis may manifest with pressure erosions of the bone similar to those of PVNS. However, it can be distinguished by the presence of multiple joint bodies, calcified or uncalcified. Synovial hemangioma is commonly associated with the formation of phleboliths. Synovial sarcoma tends to have a shorter T1 and longer T2 on MRI compared with PVNS, and when calcifications are present, the latter diagnosis can be excluded.

effective in distinguishing these entities because it can reveal hemosiderin deposition in PVNS. Although this feature may also be present in hemophilic arthropathy, detection of diffuse hemosiderin clumps, synovial irregularity and thickening, and distention of the synovial sac favors the diagnosis of PVNS. In addition, hemophilia, unlike PVNS, commonly affects multiple joints and is associated with growth disturbance at the articular ends of the affected bones. Synovial chondromatosis may manifest with pressure erosions of the bone similar to those of PVNS. However, it can be distinguished by the presence of multiple joint bodies, calcified or uncalcified. Synovial hemangioma is commonly associated with the formation of phleboliths. Synovial sarcoma tends to have a shorter T1 and longer T2 on MRI compared with PVNS, and when calcifications are present, the latter diagnosis can be excluded.

Treatment

Treatment usually consists of surgical open or arthroscopic synovectomy. Occasionally, intraarticular radiation synovectomy is used when the abnormal synovial tissue is less than 5 mm thick. Recently, reports appeared of postsynovectomy adjuvant treatment with external beam radiation therapy or intraarticular injection of radioactive material such as yttrium-90 (90Y). Local recurrence is not uncommon and is reported in approximately 50% of cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree