and Siddharth P. Jadhav2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch Pediatric Radiology, Galveston, TX, USA

(2)

The Edward B. Singleton Department of Pediatric Radiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of tumors, bone cysts, and tumor mimickers which can present to the emergency room. Various imaging modalities are addressed as are differential diagnoses. The objective is to provide an overview so that each entity is not repeated in other chapters.

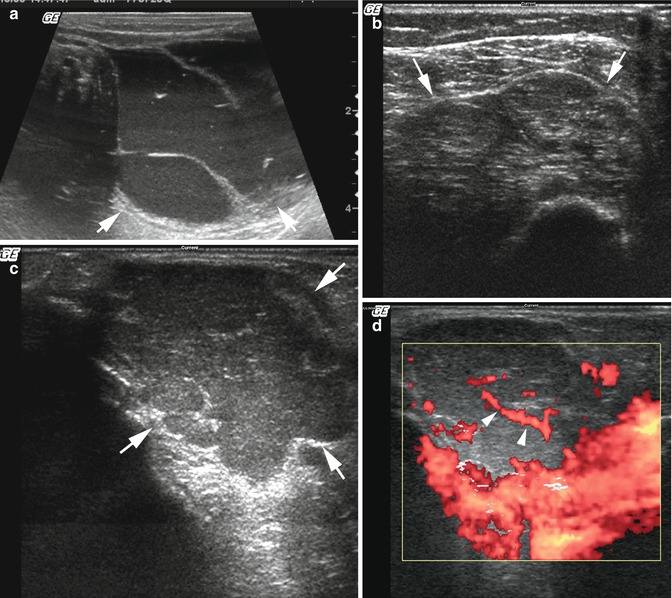

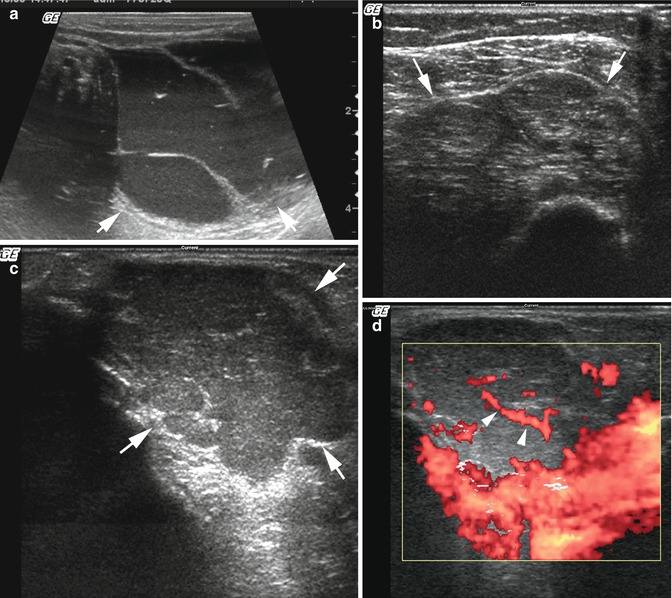

Soft tissue tumors seldom present as an acute problem in the emergency room. Every so often, a hemangioma thromboses or bleeds and a cystic hygroma becomes infected or encounters a bleed, but otherwise soft tissue tumors are more indolent. For the most part, soft tissue tumors are first evaluated with plain films where deep edema will be seen and then with ultrasound. Ultrasound is especially useful for the evaluation of hemagiomas and cystic hygromas along with their complications [1, 2] (Fig. 3.1).

Fig. 3.1

Lymphangioma/hemangioma. (a) Cystic hygroma. Note the multiloculated fluid-filled mass (arrows) with septae. The fluid is dirty because bleeding into the cystic hygroma occurred and brought the patient to the ER. (b) Hemangioma. Note the multilobulated coarsely echogenic mass (arrows). The echogenic arc at the lower end of the image is the humerus. This hemangioma was located over the patients shoulder. (c) Capillary hemangioma. Note the multilobulated coarsely echogenic mass (arrows). This is typical for a hemangioma. (d) Color flow Doppler demonstrates increased flow and feeders (arrowheads) to and within the hemangioma

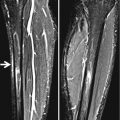

Also somewhat rare is the acute presentation of a malignant bone tumor. Once again, these entities are somewhat indolent but every so often a patient will present because of extremity pain, and imaging will demonstrate the presence of a bone tumor, occasionally with a pathologic fracture (Fig. 3.2). In the young pediatric patient, metastatic neuroblastoma is a common entity to encounter with unexplained pain. What one see in these cases is permeated bony destruction usually around the metaphysis (Fig. 3.2c). Much more commonly, however, one will encounter a pathologic fracture in a benign lesion such as a unicameral bone cyst (Fig. 3.3).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fig. 3.2

Malignant tumors. (a) Ewing’s sarcoma. Note periosteal new bone deposition (arrows) around a destructive lesion of the proximal fibula. (b) Osteosarcoma. Note moth-eaten destruction of the distal femur along with reactive sclerosis and cortical destruction (arrows). A Codman triangle also is present. (c) Neuroblastoma metastases. Note the permeated pattern of bony destruction (arrows) in the lower metaphysis of the right femur

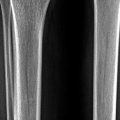

Fig. 3.3

Bone cyst. (a) Note a typical lucent bone cyst with a cortical fracture (arrow) in the proximal humerus. (b) Another patient with similar findings but, in addition, the demonstration of the “fallen fragment sign” (arrow). (c) Metaphyseal location. Note the large, lucent, and expanding lesion in the midshaft of the humerus. A fracture is present through the midportion, and in addition, there is a small fallen fragment (arrow

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree