CHAPTER 37 Tumors of the Cranial/Spinal Nerves

Primary tumors of the cranial and spinal nerves derive from the cellular and extracellular support structures of the nervous system, rather than the functional neurons per se. The tumors are generally benign, slow growing, and often asymptomatic findings. Surgery is typically reserved for symptomatic cases and cases in which rare malignant transformation is suggested. Each of the tumors may arise sporadically or be part of the constellation of pathologic processes within specific genetic conditions.

In the United States, optic nerve gliomas represent 4% of orbital tumors, 4% of intracranial gliomas, and 2% of intracranial tumors. They also comprise two thirds of all primary optic nerve tumors.1 Aggressive optic gliomas are a rare, unusual presentation of the more common adult astrocytoma.2

SCHWANNOMA

Epidemiology

The mean age at presentation of isolated schwannomas is 35 to 45 years. In patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), schwannomas may occur at a much younger age; acoustic schwannomas are the most common of these, occurring in more than 90% of patients with NF2. The rare ancient schwannoma variant occurs predominantly in elderly patients.3 A male predominance has been reported only for isolated carotid space schwannomas (involving CNs IX, X, XI, or XII). No racial predilection has been reported.

Clinical Presentation

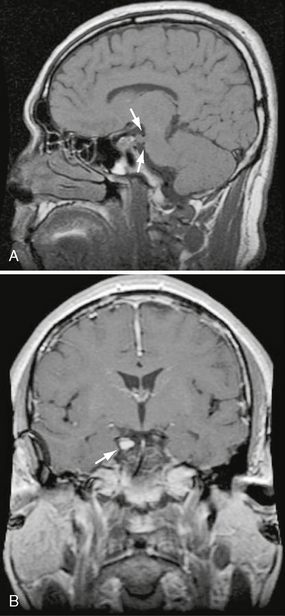

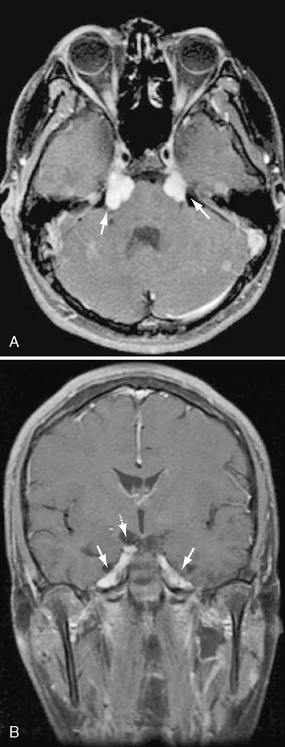

Schwannomas involving the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves are rare (Fig. 37-1). Presenting symptoms can include palsy of the affected muscle and ipsilateral cavernous sinus symptoms if the mass is in the cavernous sinus.4,5

FIGURE 37-1 A, Sagittal T1 MRI demonstrates enlargement of CN III at its root exit in the midbrain at the level of the tegmentum as it courses between the posterior cerebral and superior cerebellar arteries (arrows). B, Coronal T1W post-contrast (PC) image in the same patient demonstrates uniform enhancement of the CN III schwannoma within the suprasellar cistern (arrow) in this patient with NF2.

Trigeminal Nerve Schwannoma

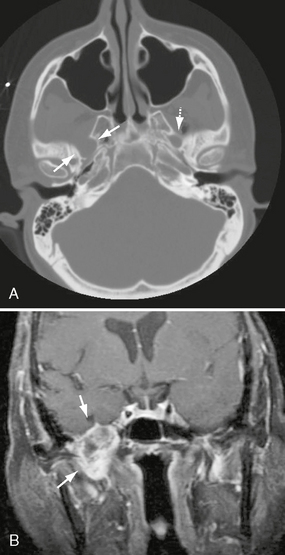

The tumor most commonly is an asymptomatic finding. Even large trigeminal nerve schwannomas of the deep face may be asymptomatic (Figs. 37-2 and 37-3). Atypical facial pain/paresthesias and masticator muscle weakness are less common presenting signs.

FIGURE 37-2 A, Axial T1W PC fat-saturated MR image shows bilateral, avid, uniform enhancement and enlargement of the cisternal segments of CN V within the prepontine cistern. Lesions are consistent with CN V schwannomas in this patient with NF2. B, Coronal T1W PC fat-saturated MR image in the same patient demonstrates extension of the enhancing schwannomas to Meckel’s cave bilaterally (solid arrows). Note additional right CN III schwannoma (dashed arrow).

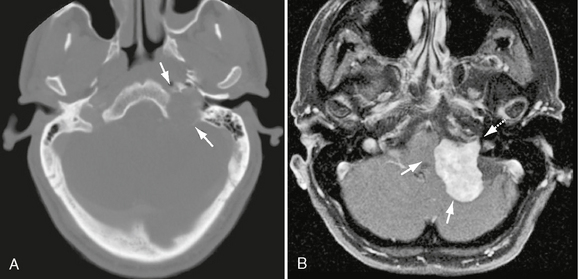

FIGURE 37-3 A, Axial bone CT through skull base demonstrates enlargement of the right foramen ovale (arrows). Note the smooth remodeling typical of growth of a V3 schwannoma and normal appearance of the left foramen ovale (dashed arrow). B, Coronal T1W PC fat-saturated MR image in a different patient demonstrates a heterogeneously enhancing V3 schwannoma expanding the right foramen ovale, extending into the infratemporal fossa (arrows).

Facial Nerve Schwannoma

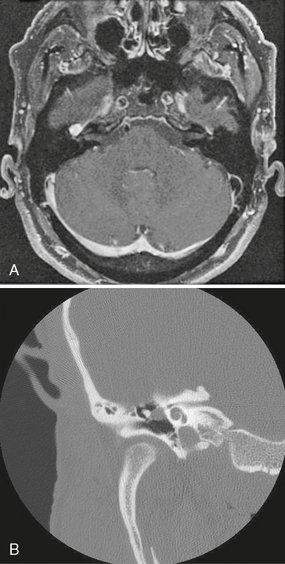

The most common presenting symptom of facial nerve schwannomas is hearing loss (present in ∼70%). Slowly progressive facial nerve paralysis occurs in about 50%. Other less common presenting symptoms include ear and facial pain, hemifacial spasm, and, rarely, an acute onset of Bell’s palsy–like facial paralysis. Cerebellopontine angle/internal auditory canal (CPA/IAC) facial nerve schwannomas most commonly present as sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, and tinnitus. Tympanic and mastoid segment facial nerve schwannomas, if large, may present as an avascular retrotympanic mass in the setting of conductive hearing loss (Fig. 37-4).

FIGURE 37-4 A, Axial T1W PC fat-saturated MR image demonstrates uniformly enhancing CN7 schwannoma centered at the right geniculate ganglion. Enhancement also extended along the proximal anterior tympanic (horizontal) segment of CN VII. B, Coronal T-bone CT of same right ear demonstrates expansion of the CN VII canal, with extension of the mass into the middle ear and apposition with the ossicles.

Jugular Foramen Schwannoma

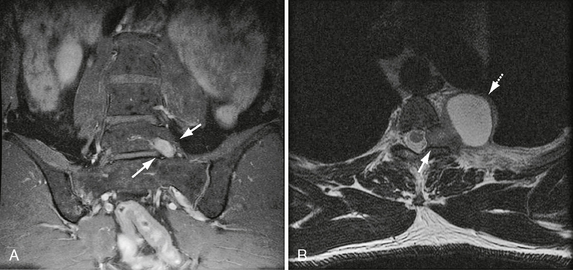

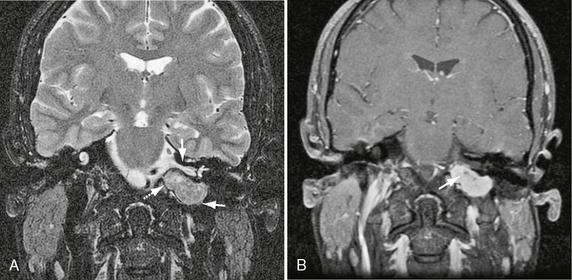

The most common presentation of jugular foramen schwannomas (involving CNs IX > X > XI) is sensorineural hearing loss (90%). This presumably results from the superomedial vector spread of these tumors (Figs. 37-5 and 37-6). CN IX to XI neuropathy occurs late in the disease progression. This may include glossopharyngeal dysfunction (e.g., hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, aspiration) and/or spinal accessory symptoms (e.g., trapezius atrophy). Hoarseness also may occur with involvement of the recurrent laryngeal branch of CN X. Other presenting signs and symptoms may include dizziness with cerebellar compression and jugular vein occlusion.

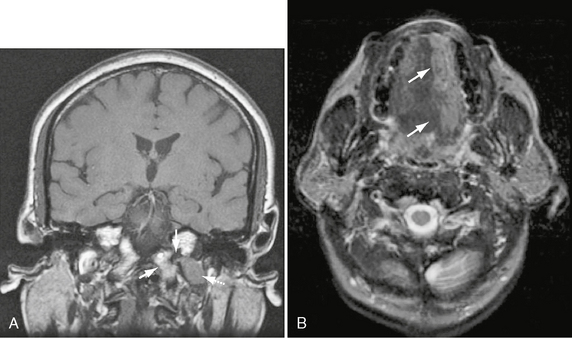

FIGURE 37-5 A, Coronal T2W MR image demonstrates classic jugular foramen schwannoma as fusiform mass (lower arrow). Note relationship of superior component to the internal auditory canal (arrow). Inferiorly, the schwannoma extends into the nasopharyngeal carotid space (dashed arrow). B, Coronal T1W PC fat-saturated MR image in the same patient shows avid schwannoma enhancement with a central focus of cystic change (arrow). Note absence of high velocity flow voids.

FIGURE 37-6 A, Axial bone CT in same patient as Figure 37-5 demonstrates significant enlargement of the left jugular foramen (arrows). Note smooth and sharp margins, which are highly suggestive of a jugular foramen schwannoma. B, Axial T1W PC fat-saturated MR image in a different patient demonstrating a CN IX schwannoma within the left jugular foramen (dashed arrow) with significant medial extension, exerting mass effect on the brain stem and cerebellum (arrows).

Hypoglossal Canal Schwannoma

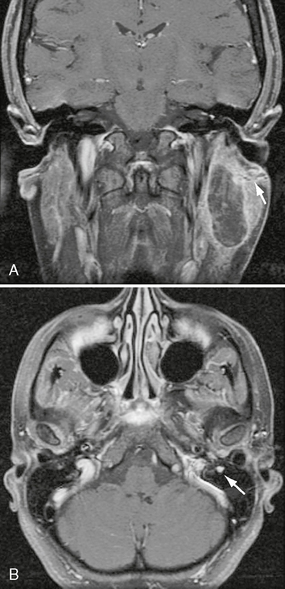

These rare lesions most commonly present as ipsilateral hemi-tongue denervation (Fig. 37-7) and occasionally as tongue fasciculations in the subacute phase. Large lesions that extend along the prepontine cistern may produce multiple lower cranial neuropathies, involving any of CNs VII to XII.

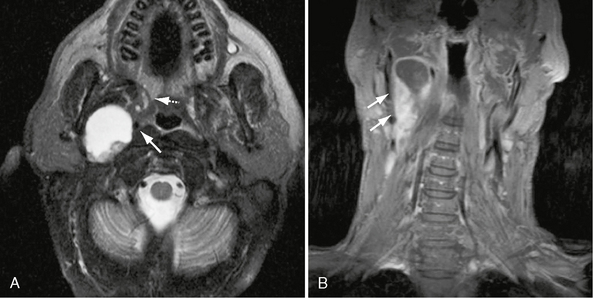

FIGURE 37-7 A, Coronal T1W MR image shows schwannoma emerging from hypoglossal canal (arrow) and extending into the most cephalad portion of the nasopharyngeal carotid space (dashed arrow). Note normal marrow signal and cortex of the jugular tubercle and occipital condyle (arrowhead). B, Axial T2W MR image in the same patient demonstrates ipsilateral hemi-tongue atrophy.

Carotid Space Schwannoma

These tumors most commonly present as an asymptomatic posterolateral pharyngeal wall mass (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal [Figs. 37-8 and 37-9]) or an asymptomatic anterolateral neck mass (cervical). Other presenting signs and symptoms include Horner’s syndrome, vocal cord paralysis, sleep apnea, and dysphagia.

FIGURE 37-8 A, Axial T2W MR image shows extensive central cystic change within right nasopharyngeal carotid space: CN X schwannoma. Sharp margins, absent high velocity flow voids, and the internal carotid artery draped over the anteromedial surface (arrow) are all consistent with the diagnosis of schwannoma. Note also anteromedial displacement of the parapharyngeal fat (dashed arrow). B, Coronal T1W PC fat-saturated MR image in the same patient shows ovoid enhancing mass with extensive cystic change (arrows), consistent with carotid space schwannoma.

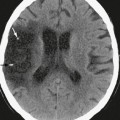

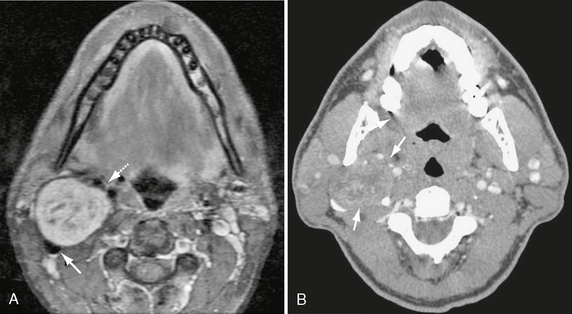

FIGURE 37-9 A, Axial T1W PC fat-saturated MR image shows enhancement of suprahyoid carotid space CN X schwannoma, with central intramural cystic change. Note anteromedial displacement of carotid vessels (dashed arrow) and posterolateral deflection/effacement of the jugular vein (arrow). B, Axial CT with contrast in same patient shows mild enhancement of the CN X schwannoma (arrows) with central areas of cystic change.

Pathophysiology

The natural history of the majority of schwannomas is that of a slow-growing benign tumor. However, 10% of acoustic schwannomas demonstrate rapid growth (≥1 cm/yr). Malignant transformation is exceedingly rare.6 Schwannomas commonly present as sporadic tumors but may present as part of the constellation of multiple inherited schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas (MISME) in the setting of NF2. Multiple peripheral schwannomas may rarely occur in the absence of other NF2 features, and this is referred to as schwannomatosis.

The vast majority of schwannomas occur as a result of sporadic mutations. Sixty percent of sporadic vestibular schwannomas specifically demonstrate inactivation of the NF2 tumor suppressor gene through point mutations, loss of the NF2 locus on chromosome 22q, or loss of chromosome 22 entirely.7,8 Carney complex is a rare autosomal dominant disease caused by mutation in the gene encoding the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A. The disease locus has been mapped to chromosome 17. Carney complex manifests as an array of pathologic processes, including melanotic schwannomas, cutaneous myxomas, potentially life-threatening cardiac myxomas, and pigmented adrenal tumors.9

Differential Diagnostic Considerations

Trigeminal Nerve Schwannoma

Differential considerations include neurofibromas (typically the plexiform type in patients with NF1), masticator space sarcomas, and perineural spread of tumors such as squamous cell carcinoma.10

Facial Nerve Schwannoma

When involving the CPA/IAC these lesions may exactly mimic acoustic schwannomas. An important distinction is extension of tumor into the labyrinthine segment of CN VII, which makes the imaging diagnosis (Fig. 37-11). Additional differential considerations include normal enhancement along the geniculate ganglion and anterior tympanic segment of CN VII (from surrounding arteriovenous plexus), perineural spread of parotid malignancy, facial nerve hemangioma, and Bell’s palsy in the setting of herpetic infection.11