Tumors of the Lungs and Bronchi

John H. Juhl

Janet E. Kuhlman

J. H. Juhl and J. E. Kuhlman: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

MALIGNANT TUMORS

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

There has been an absolute as well as a relative increase in the incidence of carcinoma of the lung in the past 40 years that is reflected in the mortality rate. In white male smokers the reported incidence of cancer of the lung is 15 to 30 times higher than in nonsmokers. Of all carcinomas this carries the highest mortality rate, but the rate may have reached a plateau in men. The incidence and mortality rate in women is now rising, with one study showing a drop in the male-female ratio from 15:1 in the years 1955 to 1959 to 6:1 in the years 1968 to 1971.56 By 1987, the ratio had dropped to about 2:1, with an incidence of 20% of all cancers in men and 11% in women.65 This appears to be related to an increase in the number of female smokers and probably to an increase in environmental exposure to cigarette smoke. An increase in all cell types of lung cancer occurs in cigarette smokers, and it is estimated that 85% of all lung cancer deaths are associated with cigarette smoking.56 There also appears to be an increase in lung cancer in persons exposed to secondhand smoke, asbestos, silica, lipids, hydrocarbons, arsenic, beryllium, uranium, chromate, nickel, vinyl chloride, radon gas, radiation, and bis-chloromethyl ether (BCME) and in those with a number of pulmonary conditions such as fibrosis, probably pulmonary tuberculosis, and other chronic bronchopulmonary infections. The number of persons studied does not allow a final conclusion as to cell type predominance in these groups. However, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, the most common cancer of men in the world, and the most common fatal cancer in American women.56

Classification of Malignant Lung Tumors

Numerous classifications of histologic types of lung tumors have been described, and several are now used by various groups. This lack of agreement makes it difficult to compare the numerous studies regarding incidence or predominance of various cell types associated with various carcinogens. The World Health Organization classifies malignant lung tumors into four major cell types81 (Table 29-1).

Various reports regarding the incidence of the cell types are available. Recent estimates are as follows56:

Adenocarcinoma—50% (17.9% in men, 45.1% in women)

Squamous-cell carcinoma—30% (41.3% in men, 18.6% in women)

Small-cell carcinoma—15% (19.4% in men, 11% in women)

Undifferentiated large-cell carcinoma—fewer than 5%

Mixed histologies also occur within the same tumor mass, the most common of which is adenosquamous carcinoma.56

A considerable difference in the incidence of the various cell types was found in the Early Lung Cancer Cooperative Study done by Johns Hopkins University, the Mayo Clinic, and the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.72 A total of 31,360 men, all heavy cigarette smokers 45 years of age or older, were monitored for at least 5 years. Of the 223 lung cancers detected in this group, cell types were as follows: squamous-cell, 42%; adenocarcinoma, 32%; large-cell, 15%; and small-cell, 10%. The varied results in these large studies emphasize the problem of obtaining accurate statistics on the relative incidence of the various cell types.37 Since the Early Lung Cancer Cooperative Study, however, an increasing frequency of adenocarcinoma and a decreasing frequency of squamous-cell carcinoma has been observed, and it is now recognized that adenocarcinoma is the most frequently found lung cancer.56

Despite the advances in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the overall 5-year survival rate from lung cancer remains very low, in the range of 10% to 15%.56 In contrast,

the 5-year survival rate for patients with small peripheral lung cancers staged as T1 lesions is greater than 50% after surgical resection.59 This suggests that there is an opportunity to decrease the high mortality rate in this type of cancer. Earlier diagnosis by means of radiographic examination is one way in which it may be accomplished. There are more than 160,000 new cases of lung cancer per year and 140,000 deaths per year in the United States.56,66 The majority appear to be caused by cigarette smoking.

the 5-year survival rate for patients with small peripheral lung cancers staged as T1 lesions is greater than 50% after surgical resection.59 This suggests that there is an opportunity to decrease the high mortality rate in this type of cancer. Earlier diagnosis by means of radiographic examination is one way in which it may be accomplished. There are more than 160,000 new cases of lung cancer per year and 140,000 deaths per year in the United States.56,66 The majority appear to be caused by cigarette smoking.

There are conflicting reports regarding the efficacy of screening the high-risk group (smokers older than 45 years of age) using chest roentgenograms, and there is no general agreement that earlier detection would result in decreased mortality. However, in the Cooperative Study, approximately 40% of radiologically visible cancers were stage I, with a 5-year survival rate after resection of almost 80%.72 Therefore, it appears that screening warrants further study and consideration.43 However, there is no consensus that screening is of value, because mortality rates have not decreased. In patients in the high-risk group who desire a screening chest radiograph, there is very little reason to withhold the examination. Furthermore, the radiologist who interprets chest roentgenograms in patients with a long history of smoking should make certain that all roentgenograms are of good technical quality and should attempt to double-read each radiograph, because independent double reading appears to improve sensitivity.

The adenocarcinoma, with an overall incidence of about 50%, is the most common of the bronchogenic tumors.56 Adenocarcinoma is the most common cell type found in women and nonsmokers.56 This tumor type is found in association with chronic lung disease such as focal fibrosis (scar carcinoma), diffuse fibrosis (as in interstitial fibrosis and scleroderma), chronic tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, and infarction.56 Adenocarcinoma typically appears as a peripheral mass with lobulated or irregular margins. Pleural retraction or tethering may be seen. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) may demonstrate an air bronchogram in the mass or nodule.30 Adenocarcinoma tends to be more peripheral than the other types, but in one study about 50% occurred centrally, as a hilar or mediastinal mass or as a combination of the two.80 This is the tumor most often observed peripherally in relatively young women. When adenocarcinoma of the lung spreads to the pleura, it can produce chest film and CT findings that are indistinguishable from those of other pleural neoplasms such as malignant mesothelioma.

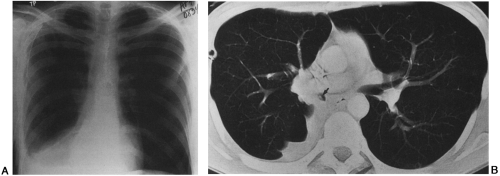

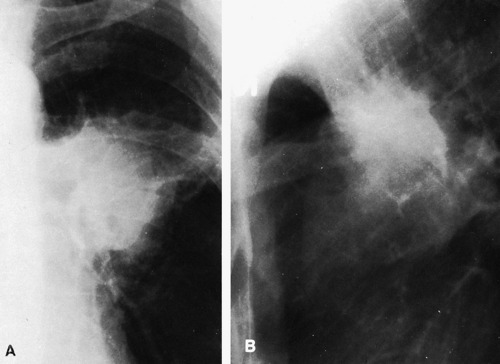

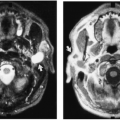

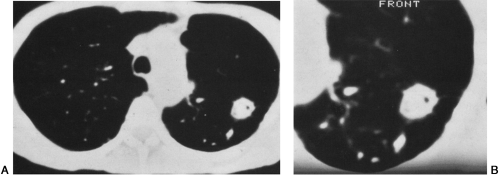

The bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC), is a subtype of adenocarcinoma making up approximately 2% to 6% of lung cancers.56 Thirty percent to 50% of BAC cases occur in women.23 BAC begins as a single focus of tumor arising in the air spaces distal to any recognizable bronchus and has a unique propensity for subsequent growth along the alveolar walls and septa (lepidic spread).29 Aerogeneous spread of tumor cells to other parts of the lung results in diffuse pulmonary disease, whereas distant metastases occur via lymphatic and hematogenous routes.70 Two general gross pathologic types are described: (1) the tumor-like or nodular form, which appears as a well-circumscribed, peripheral, solitary nodule (Fig. 29-1), and (2) the diffuse type, which roentgenographically may resemble lobar, segmental, or diffuse pneumonic consolidation (Fig. 29-2) or multifocal nodular disease. Patients with the solitary nodule form generally have a good prognosis after resection of the tumor, whereas those with the diffuse or multifocal form have limited life expectancy.23 There are also two histologic subtypes related to the predominant type of tumor cells: columnar cells (bronchiolar type) or cuboidal cells (alveolar type). Many BACs show mixed histologies, with cuboidal type II alveolar pneumocytes, nonciliated bronchiolar (Clara) cells, or mucin-secreting bronchiolar cells.23 Rarely a multicystic appearance occurs, which may or may not be associated with other solid lesions.

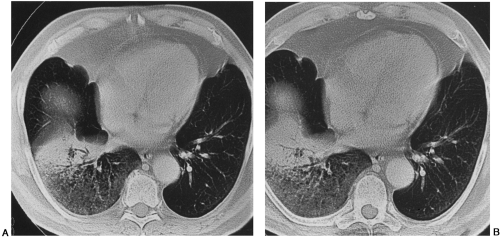

FIG. 29-1. A and B: Solitary form of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Computed tomogram shows a well-circumscribed, peripheral, solitary nodule with small lucencies in the nodule and pleural tags. |

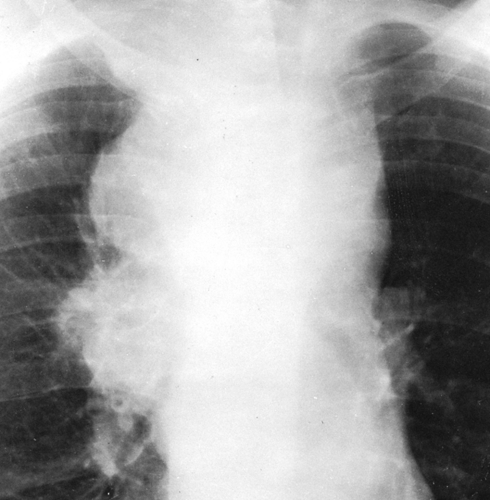

FIG. 29-2. Diffuse form of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. The chest radiograph shows bilateral air-space disease with air bronchograms, an appearance that resembles diffuse pneumonia. |

There is wide variation in the clinical course of the disease. Progression may be very slow or exceedingly rapid. Patients with a peripheral solitary BAC may be asymptomatic and the tumor may show little or no growth for years.29,70 Cough and dyspnea are prominent symptoms. Occasionally the cough may produce large amounts of mucoid sputum. In a review of 136 cases, Hill21 found a nodule smaller than 4 cm in 23%, a mass larger than 4 cm in 20%, diffuse nodules in 27%, consolidation in one lobe or less in 7%, and diffuse consolidation in 23%. Bronchial dilatation and/or distortion, with air bronchogram best demonstrated by CT, appears to be characteristic in those cases with consolidation. Air bronchograms tend to be present in the bronchiolar cell type but not in the alveolar cell type.58

A number of authors have described various CT patterns

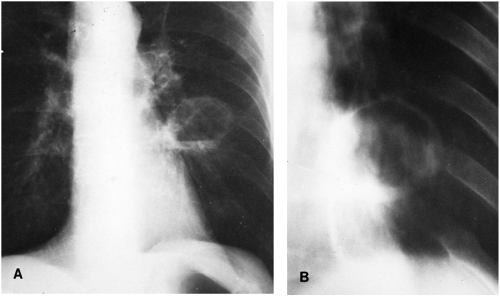

seen in patients with BAC. These include widespread or patchy ground-glass opacities in the diffuse pneumonic form of the tumor23,28; pseudocavitation, heterogeneous CT attenuation, and small lucencies in solitary BAC tumors23,29 (see Fig. 29-1); stellate borders and pleural tags in solitary masses29; the CT angiogram sign (an enhancing branching vessel within an area of low attenuation consolidation), most often seen in mucin-producing BAC22; and the air bronchogram or open bronchus sign, seen in the pneumonic and focal form of the cancer23,75 (Fig. 29-3). Many of these features are attributable to the tumor’s unique growth pattern, in which malignant cells proliferate along the alveolar walls without destroying the underlying lung architecture. Air-space disease results from filling of the alveoli with mucin (low attenuation on CT), secretions, and sloughed tumor cells; the bronchi and pulmonary vessels typically remain patent. Lucencies within areas of tumor correlate with patent dilated small bronchi or cystic air spaces at pathology.23 Other, less common CT patterns include multinodular miliary disease1 and multiple thin-walled cystic or cavitary lesions.78

seen in patients with BAC. These include widespread or patchy ground-glass opacities in the diffuse pneumonic form of the tumor23,28; pseudocavitation, heterogeneous CT attenuation, and small lucencies in solitary BAC tumors23,29 (see Fig. 29-1); stellate borders and pleural tags in solitary masses29; the CT angiogram sign (an enhancing branching vessel within an area of low attenuation consolidation), most often seen in mucin-producing BAC22; and the air bronchogram or open bronchus sign, seen in the pneumonic and focal form of the cancer23,75 (Fig. 29-3). Many of these features are attributable to the tumor’s unique growth pattern, in which malignant cells proliferate along the alveolar walls without destroying the underlying lung architecture. Air-space disease results from filling of the alveoli with mucin (low attenuation on CT), secretions, and sloughed tumor cells; the bronchi and pulmonary vessels typically remain patent. Lucencies within areas of tumor correlate with patent dilated small bronchi or cystic air spaces at pathology.23 Other, less common CT patterns include multinodular miliary disease1 and multiple thin-walled cystic or cavitary lesions.78

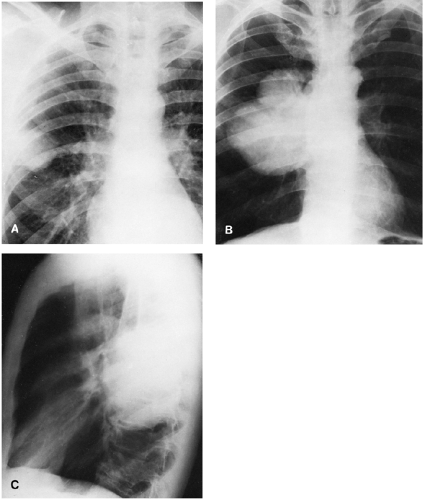

The epidermoid or squamous-cell neoplasm occurs predominantly in men, with a male-female ratio of 2:1 or 3:1, and is strongly associated with cigarette smoking. These lesions make up about one third of all bronchogenic tumors and tend to occur in relatively older age groups, with the peak incidence at age 60 years. This tumor often arises in or immediately adjacent to lobar and segmental bronchi but is occasionally peripheral (Fig. 29-4). Patients with central endobronchial tumors often present with partial or complete lobar atelectasis and postobstructive pneumonia. When a primary tumor is noted to invade the thoracic wall, it is more likely to be epidermoid than any other type, and squamous-cell carcinoma is the most common cause of the Pancoast syndrome. Necrosis with formation of cavity may also occur (10%),56 and when a tumor with cavitation is found in an elderly man it is almost always epidermoid in origin. The well-differentiated squamous-cell tumor is more likely to remain confined to the bronchus of origin and adjacent nodes than are the other cell types, and the rate of growth is often less rapid than in the others. Invasion of veins with hematogenous metastasis does occur late in the course of the disease, however. Because of the central bronchial location of many of these tumors, squamous-cell carcinoma is the most likely occult tumor type to be detected by sputum cytology. It is also the most common type of lung cancer to cause hypercalcemia as paraneoplastic syndrome.56

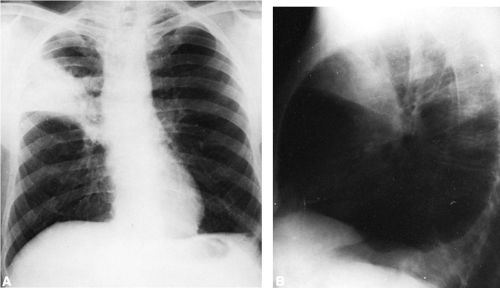

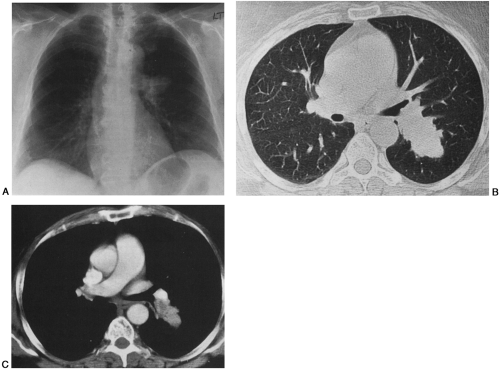

The small-cell carcinoma, which makes up about 15% of bronchogenic tumors, often occurs centrally, with hilar enlargement and massive mediastinal lymph-node metastases (Fig. 29-5). This type of lung cancer may resemble mediastinal lymphoma, and it is the most common lung cancer to cause superior vena cava obstruction.56 It does not often arise as a peripheral tumor but rarely appears as a solitary pulmonary mass. The tumor usually does not undergo necrosis

to form cavitation. Small-cell carcinomas belong to a family of neuroendocrine neoplasms of varying degrees of malignancy that includes carcinoid and atypical carcinoid tumors. These tumors contain neurosecretory granules and may secrete chemically active substances such as ectopic hormones. Small-cell carcinoma is the most common lung cancer to cause Cushing’s syndrome and secretion of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH).56

to form cavitation. Small-cell carcinomas belong to a family of neuroendocrine neoplasms of varying degrees of malignancy that includes carcinoid and atypical carcinoid tumors. These tumors contain neurosecretory granules and may secrete chemically active substances such as ectopic hormones. Small-cell carcinoma is the most common lung cancer to cause Cushing’s syndrome and secretion of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH).56

The undifferentiated large-cell carcinomas, which are also anaplastic tumors, comprise about 5% of lung cancers. They tend to be large, bulky tumors and usually occur peripherally, but they can occur centrally. Necrosis is often a prominent feature. Pleural involvement with effusion is common. As their name implies, these tumors are more aggressive and spread early, both locally and through distant metastases.56

Roentgen Findings in Lung Cancer

The changes caused by bronchogenic carcinoma vary widely, depending on the site of the tumor and its relation to the bronchial tree.55 The tumor itself may or may not be visible. When the tumor is not visible, its presence can be detected by such findings as localized atelectasis and inflammatory disease, secondary to the tumor within or compressing a bronchus. Each radiologic sign of bronchogenic carcinoma may occur as the only evidence of tumor, or several of the signs may occur in a single patient. Any of the following may occur as the initial sign of bronchogenic carcinoma:

Unilateral hilar enlargement (Fig. 29-10)

Overinflation, obstructive in type, which may be segmental or lobar; this is a very rare sign

Mediastinal mass, often simulating lymphoma; this is usually found in small-cell carcinoma (see Fig. 29-5)

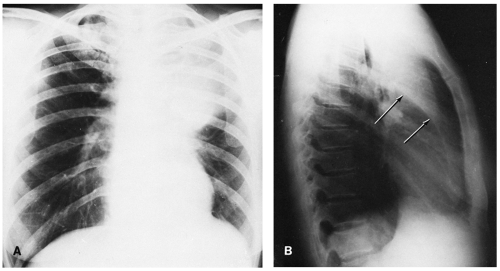

Apical pulmonary opacity with or without rib destruction; this is the superior pulmonary sulcus (Pancoast) tumor (Fig. 29-11)

Cavitation in a solitary mass, usually in squamous-cell carcinoma in heavy smokers (Fig. 29-12)

Segmental consolidation resembling local pneumonitis, which does not clear or which clears incompletely (Fig. 29-13)

Parenchymal mass—a solitary mass or nodule larger than 4 cm in diameter is usually malignant (Fig. 29-14). Rarely, a hamartoma or granuloma may attain this size. The mass or nodule may be sharply defined but is more often poorly defined and irregular; it may be surrounded by abnormal thickened vessels or spiculation best demonstrated on CT

Mucoid impaction distal to a small endobronchial tumor may be visible when a segmental bronchus is involved, because collateral ventilation may result in aeration of the distal lung. A persistent round or fusiform shadow, often with branching, is observed. It appears similar to mucoid impaction in allergic aspergillosis but is local and persistent rather than transitory and multifocal (Fig. 29-15)

Occasionally the initial sign is a very poorly defined, irregular, nonhomogeneous density that may be linear and may resemble a fibrotic scar. Therefore, it is necessary to be suspicious of almost every opacity in the lung that does not clear or that appears in a patient with previously normal lungs, particularly if the patient is a male smoker older than 40 years of age.

In addition to those listed, a number of other roentgen signs may result from metastasis or local invasion. These include pleural effusion, hematogenous or lymphangitic intrapulmonary metastasis, elevation of the diaphragm secondary to phrenic nerve paralysis, and pleural masses with or without rib destruction.

Atelectasis

Atelectasis is probably the most common single radiographic sign of bronchogenic carcinoma. There may be segmental, lobar, or massive atelectasis of one lung. The radiographic signs of atelectasis resulting from tumor are similar to those caused by any lesion producing endobronchial block. The amount of opacity produced varies with the size of the bronchus obstructed. It is not uncommon to find a combination of atelectasis and tumor (see Figs. 29-6, 29-7, 29-8, and 29-9). This is most readily seen in the right upper lobe, where the atelectasis results in elevation and concavity of the secondary interlobar fissure laterally. A convexity medially with greater opacity there represents the tumor mass. In such patients the inferior margin of the lobe resembles the reversed letter S (Golden’s sign). A combination of pneumonia and atelectasis may also occur, which may cause confusion. Persistence of the shadow despite antibiotic therapy or failure of complete disappearance is strong evidence of neoplasm. Occasionally a relatively central mass is visible in association with a more peripheral density representing atelectasis, infection, or infarction in various combinations distal to the central tumor.

Unilateral Enlargement of the Hilum

Unilateral enlargement of the hilum (see Fig. 29-10) may be very difficult to evaluate when only a single roentgenogram is available. If there is a difference in the size of the hilum on the two sides, every effort should be made to obtain any previous roentgenograms of the patient that may be available. If a film of an earlier examination is obtained, any difference in hilar size between the two films is of particular significance. CT with intravenous contrast enhancement, preferably with spiral or helical technique, should next be obtained to outline the tumor or local bronchial narrowing produced by it and to detect hilar lymph nodes.

Local Overinflation (Obstructive)

Bronchogenic carcinoma may not cause enough obstruction to interfere with air entering the segment, lobe, or lung supplied by the bronchus, but the slight decrease in bronchial size on expiration may result in partial obstruction to the egress of air. This causes overinflation, which may precede atelectasis by a considerable period of time. It is a rare sign of bronchogenic carcinoma. Films in inspiration and expiration and fluoroscopy accentuate the findings and may verify the presence of obstructive overinflation, but these methods are

rarely pursued given the greater amount of information that can be obtained by going directly to CT examination. When a wheeze is detected on auscultation or the presence of local overinflation is suggested on the chest roentgenogram, helical CT scanning with narrow collimation and overlapping slice reconstruction is indicated to search for a subtle endobronchial lesion. If obstructive overinflation is found in a patient past middle age, bronchogenic carcinoma should be suspected. Then further evaluation with CT and bronchoscopy should be undertaken.

rarely pursued given the greater amount of information that can be obtained by going directly to CT examination. When a wheeze is detected on auscultation or the presence of local overinflation is suggested on the chest roentgenogram, helical CT scanning with narrow collimation and overlapping slice reconstruction is indicated to search for a subtle endobronchial lesion. If obstructive overinflation is found in a patient past middle age, bronchogenic carcinoma should be suspected. Then further evaluation with CT and bronchoscopy should be undertaken.

Mediastinal Widening

When the mediastinum is enlarged as a result of bronchogenic carcinoma, it often indicates the presence of a small-cell type of tumor. The primary tumor is usually in a stem

bronchus and rarely beyond a lobar bronchus, so the primary tumor mass is often obscured by a large mediastinal mass. Therefore this tumor cannot be differentiated from lymphoma in some patients. The tumor is nonresectable when there is mediastinal invasion, but it may respond to irradiation or chemotherapy, or both (see Fig. 29-5).

bronchus and rarely beyond a lobar bronchus, so the primary tumor mass is often obscured by a large mediastinal mass. Therefore this tumor cannot be differentiated from lymphoma in some patients. The tumor is nonresectable when there is mediastinal invasion, but it may respond to irradiation or chemotherapy, or both (see Fig. 29-5).

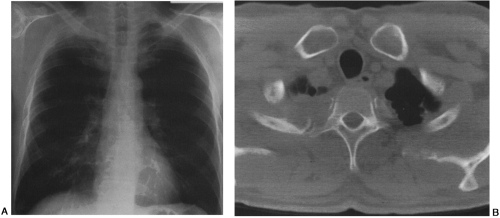

Apical Density With or Without Rib Destruction

Apical density with or without rib destruction denotes the presence of a superior pulmonary sulcus tumor known as a Pancoast tumor. It is usually caused by either squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, but other cell types may be found. The four cardinal signs of the Pancoast syndrome are (1) mass in the pulmonary apex, (2) destruction of an adjacent rib or vertebra, (3) Horner’s syndrome caused by tumor involvement of the stellate ganglion of the sympathetic chain, and (4) pain or atrophy of the muscles of the ipsilateral arm resulting from tumor involvement of the brachial plexus.56 In addition to bronchogenic carcinoma, other tumors, including metastatic carcinoma and malignant neurogenic tumor, can cause the Pancoast syndrome. When only a small amount of parenchymal density or asymmetrical apical pleural thickening is visible representing the peripheral tumor, the diagnosis of malignancy is very difficult to make, because this density simulates the minor amount of pleural thickening often seen in the apex in elderly patients. The presence of pain should lead to the strong suspicion of tumor, and the other clinical findings of Horner’s syndrome, loss of sensation in the forearm, atrophy of the hand muscles make the diagnosis almost certain. The tumor can grow rapidly and produce early destruction of the ribs (see Fig. 29-11). O’Connell and associates48 reviewed 29 patients with this tumor. An apical mass was found in 45%, and 55% had unilateral apical pleural thickening. The apical lordotic view can be misleading in the detection of occult Pancoast tumors. Oblique projections may be helpful, but better delineation of the apical abnormality is often best obtained with examination of the apices by thin-section CT. Needle biopsy is the best nonsurgical method of establishing the diagnosis. In cases of known Pancoast tumor, CT can demonstrate the extent of bone disease, particularly the presence of rib and

vertebral body destruction, which is found in 34%. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the more accurate imaging modality for staging the extent of soft-tissue involvement by the Pancoast tumor.19 MRI has the advantage of direct multiplanar imaging and is better at delineating invasion of the brachial plexus, spinal canal, and cervical and thoracic soft tissues.

vertebral body destruction, which is found in 34%. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the more accurate imaging modality for staging the extent of soft-tissue involvement by the Pancoast tumor.19 MRI has the advantage of direct multiplanar imaging and is better at delineating invasion of the brachial plexus, spinal canal, and cervical and thoracic soft tissues.

Solitary Cavity

If a solitary cavity is found in an elderly man who has few if any signs of infection, the presence of bronchogenic carcinoma should be suspected. The cavity wall is usually thick and irregular, but it may be very thin, at least in some areas. If CT studies are obtained, almost invariably a local mass is seen projecting from the round or oval cavity wall into the cavity in one or more areas. Another helpful sign is the lack of evidence of inflammatory disease in the vicinity of the solitary cavity (see Fig. 29-12). The epidermoid tumor is the usual type in which cavitation occurs; necrosis leads to the cavitation. Most of these tumors are found in the upper lobes. A long history of smoking is common in these patients. Rarely, adenocarcinoma and large-cell carcinoma may cavitate, but small-cell carcinoma does not.

Pneumonitis That Does Not Clear

Partial obstruction of a bronchus by a tumor can cause inflammatory disease in the lobe or segment supplied by that bronchus. On radiographic study, the findings simulate those of an ordinary pneumonia localized to the area. If the process fails to resolve or clears incompletely, bronchogenic carcinoma should be suspected (see Fig. 29-13). Further, if the pneumonitis clears and then reappears in the same area, endobronchial tumor should also be suspected, and further studies including CT and bronchoscopy should be carried out to determine the cause. The opacity noted in these patients with disease that resembles pneumonia may be caused in part by tumor; CT may then outline tumor nodulation within the area of pneumonic consolidation. An air bronchogram is occasionally observed in this situation. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) may simulate segmental or lobar pneumonia, as indicated previously. This opacity does not clear (see Fig. 29-3). Air bronchogram is commonly seen, and CT often reveals dilated or distorted bronchi, or both.

Smaller, poorly defined opacities resembling very small patches of inflammatory disease may actually represent the first sign of bronchogenic carcinoma. When such a lesion is found, particularly in a smoker, it is important to obtain follow-up roentgenograms and also to obtain previous roentgenograms, if available, for comparison. When such a lesion does not respond to antibiotic therapy and does not contain calcium, bronchogenic tumor is a distinct possibility.

Large Parenchymal Mass

Bronchogenic carcinoma that begins as a peripheral nodule may reach a very large size before causing symptoms. These large, lobulated but generally round or oval masses may lie far out in the periphery or adjacent to the hilum. They usually range from 4 to 12 cm in diameter, and sometimes are even larger. CT may show some areas of radiolucency, indicating necrosis within the mass. There is usually very little difficulty in arriving at the diagnosis of pulmonary carcinoma in these patients, because any solitary mass of large size in a patient in the age group at risk for carcinoma is most likely malignant and must be considered as such until disproved. There is often associated hilar-node involvement resulting in unilateral hilar enlargement (see Fig. 29-10).

Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

The solitary peripheral pulmonary parenchymal nodule presents a diagnostic and therapeutic problem that has been extensively investigated and discussed.17,85,87 When such a nodule is seen on a chest roentgenogram, the question of lung tumor always arises. These nodules may range from a few millimeters up to 4 cm or more in size. When they are larger than 2.5 cm and contain no calcium, it is highly probable that they are bronchogenic carcinomas. Surgical resection of the solitary nodular bronchogenic carcinoma results in a higher 5-year survival rate than in lung cancer in which symptoms are present. The prognosis is better when the lesions are smaller than 2 cm in diameter and much better in patients younger than 55 years of age. Lillington,32 in a comprehensive review of solitary pulmonary nodules, concluded that (1) most benign nodules are granulomas; (2) most resected nodules are malignant; (3) surgical mortality is low for resection of nodules; (4) prognosis is better than in other types of lung cancer; and (5) resection of nodular metastasis results in prolonged survival in a significant number of cases.

Detection of a solitary pulmonary nodule is therefore very important. As indicated previously, double reading is very helpful in decreasing the number of false-negative results. CT has replaced oblique films and fluoroscopy whenever there is a question as to the location of a nodule seen on only one projection. Nodules can be seen when they are 3 mm in diameter, but true tumors can be separated from opacities that mimic them only when they are 8 to 10 mm in diameter. Many methods have been tried to improve radiographic detection of pulmonary nodules. Most have showed promise, but there is no consensus regarding a single best method.61,73 Many other studies have been reported in addition to those cited here.39

Although mass screening of adults older than 45 to 50 years is probably not cost-effective, the screening of heavy smokers older than 45 years of age—and particularly of asbestos workers who are heavy smokers—may prove to be effective. When a small nodule is found, certain steps should

be taken to ascertain the nature of the lesion. If previous films are available, they should be reviewed. If the lesion was not present on films made within the preceding 1 or 2 years in a patient (particularly a smoker) older than 40 years of age, malignant tumor is the first consideration. Inflammatory granulomas occasionally appear in patients of middle age, but this is uncommon. If the nodule has undergone no increase in size for at least 2 years, it is more likely to be benign but should be observed at intervals for several more years.

be taken to ascertain the nature of the lesion. If previous films are available, they should be reviewed. If the lesion was not present on films made within the preceding 1 or 2 years in a patient (particularly a smoker) older than 40 years of age, malignant tumor is the first consideration. Inflammatory granulomas occasionally appear in patients of middle age, but this is uncommon. If the nodule has undergone no increase in size for at least 2 years, it is more likely to be benign but should be observed at intervals for several more years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree