Chapter 30 Tumours of the central nervous system

Introduction

Tumour types

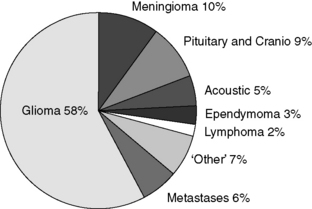

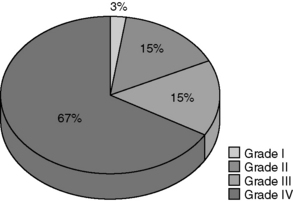

The major types of primary tumour are given in Table 30.1, and the percentages of these tumour types in our own practice are shown in Figure 30.1. The majority of tumours (58%) are gliomas (Figure 30.1). Of the gliomas, two-thirds are glioblastomas (Figure 30.2), making this the most common type of primary CNS tumour in adults. Gliomas in general, and glioblastomas, in particular, are devastating tumours, and therefore consume much of the energy and resources of the neuro-oncology unit. Although gliomas represent the major diagnosis of primary brain tumours, over a third of new referrals are for other tumour types, so appropriate attention also needs to be directed towards those.

Table 30.1 A simplified classification of the major categories of brain tumour

Intrinsic tumours (i.e. those arising within the brain substance) Extrinsic tumours of the brain covering Meningioma Other tumours Cerebral metastases |

Notes:

1. Glioblastoma used to be known as ‘glioblastoma multiforme’

2. The glial tumours are divided into four grades: grade I and II together constitute low-grade gliomas (LGGs), while grade III and IV tumours together are the high-grade gliomas (HGGs). The term ‘anaplastic’ is equivalent to a grade of III. A grade IV glioma is a GBM.

3. Grade I tumours are rare in adults, though they do occur. They also appear in adult practice in patients treated as children who have outgrown the paediatric services.

4. A large number of other uncommon tumours also occur.

5. Medulloblastoma is predominantly a disease of childhood, but does occasionally occur in adults (i.e. patients over 16).

Gliomas arise from astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, cells which nourish and support neurons. Primary tumours of neurons alone are extremely uncommon, though they do exist (e.g. neurocytoma). There is a surprising large range of very rare tumours within the brain, but apart from those mentioned explicitly in Table 30.1, and described below, their overall management and outcome can generally be inferred from the grade of the tumour.

Anatomy of the CNS

Anatomy of the brain

The major structures of the brain

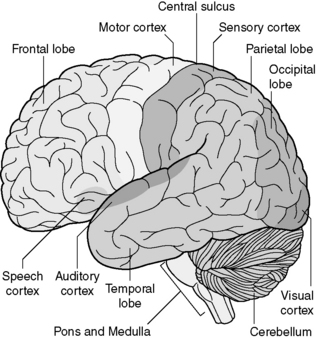

Figure 30.3 shows the outside of the brain to explain the nomenclature of the principal lobes. In right-handed patients, the left hemisphere is almost invariably dominant.

The frontal lobe is very large, extending back to the central sulcus, which divides it from the parietal lobe. The motor cortex sits immediately in front of the central sulcus. More anteriorly, the frontal lobe is responsible for intellect, motivation and emotional response. Damage to the frontal lobes can affect intellectual performance, including reasoning, memory, the initiation of activity and insight. The medial frontal lobe is particularly important for these activities and damage to both medial frontal lobes is extremely destructive to the intellect. The motor speech centre (Broca’s area) lies in the dominant frontal lobe (see Figure 30.3).

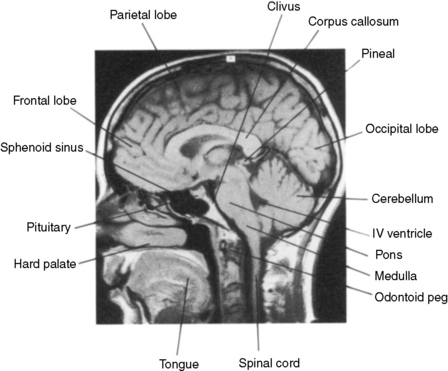

The pons and medulla together form the brainstem. These have processing functions, important functional centres such as the respiratory centre, and also carry all motor and sensory information between the cerebral cortex and spinal cord (Figures 30.3 and 30.4). Even small lesions within the brainstem have very severe neurological effects. The function of the cerebellum is the subconscious control of movement. Damage to the cerebellum therefore leads to ataxia and other difficulties with coordinated movement.

Figure 30.4 Normal anatomy of the central nervous system. MR midline sagittal section.

(Courtesy Dr L Turnbull, MRI Unit, Sheffield)

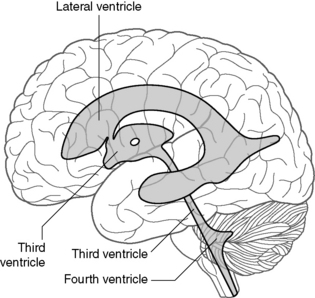

The lobes of the brain communicate by extensive pathways made up of white matter. These run from front to back, side to side, and up and down through the brain. Tumours which spread through white matter tracts (especially the gliomas) therefore have access to pathways which can allow them to spread extensively. The corpus callosum (see Figure 30.4) is the major route of side to side communication between the two cerebral hemispheres. High-grade gliomas lying medially in the hemisphere often involve this structure, which allows spread into the opposite hemisphere.

Anatomy of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways and hydrocephalus

The major cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) structures are shown in Figure 30.5. CSF is produced by the choroid plexus within the two lateral ventricles, and flows into the third ventricle anteriorly through the foramen of Munro (Figure 30.5). CSF exits the third ventricle posteriorly through the aqueduct, and flows into the fourth ventricle. From there, CSF leaves the fourth ventricle through three foramina (the foramina of Luschka laterally and the foramen of Magendie in the midline) to surround the outside of the brain. A small amount also passes down the central canal in the spinal cord. CSF is actively absorbed by the arachnoid granulations which protrude into the major venous sinuses, especially the superior sagittal sinus at the vertex of the skull. The CSF canals are lined by ependymal cells, from which ependymomas arise. These tumours are therefore related in space to the ventricular system.

Clinical features – presentation of brain tumours

Specific focal neurological deficit

Symptoms and signs relating to specific parts of the brain are as follows:

Principles of management

Performance status in the treatment decision

Performance status is an important predictor of outcome, including survival, particularly for patients with glioma (Table 30.2). It also indicates how well the patient is likely to tolerate treatment. This is an important factor when recommending a treatment program. The choice can be between radical, palliative, or active supportive care. For patients with disabling neurology, especially those with GBM, supportive care may be the most appropriate option.

Table 30.2 WHO performance status and Glasgow coma scale (GCS).

| The WHO Performance Status is useful in assessing patient capabilities, especially with respect to activities of daily living. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a measure of conscious level. |

| WHO performance status | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 = Able to carry out all normal activity without restriction | ||

| 1 = Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out light work | ||

| 2 = Ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work; up and about >50% of waking hours | ||

| 3 = Capable of only limited self-care; confined to bed or chair >50% of waking hours | ||

| 4 = Completely disabled. Cannot carry out any self-care; totally confined to bed or chair | ||

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) | ||

| Eyes open | Spontaneously | 4 |

| To speech | 3 | |

| To stimulus | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Best verbal response | Orientated | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Best motor response | Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localize stimulus | 5 | |

| Flexion – withdrawal | 4 | |

| Flexion – abnormal | 3 | |

| Extension | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| Best score 15 | ||

| Worst 3 | ||

Principles of additional supportive care

Supportive input may be valuable to a patient throughout their journey. Needs vary according to tumour type, and may fluctuate throughout the patient’s journey, with treatment or progression. Many patients benefit from practical and psychological support. The relevant support is often best developed by a specialist nurse, who will be part of most neuro-oncology teams. Key roles are liaison with the patient and family, other healthcare professionals and hospice services, and provision of information from local or general resources, such as Cancer BACUP (http://www.cancerbacup.org.uk/Home). For some patients, especially those with gliomas, financial benefits may be available.

Driving after a diagnosis of CNS tumour

Decisions about licensing are made by the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA), though with information provided from the clinical teams. In general, the DVLA will help patients to regain a license, and will provide an individualized decision in unusual circumstances. The DVLA provides information on the guidelines for return of licenses for medical practitioners which can be obtained from the DVLA website (www.DVLA.gov.uk). It is worth using this on-line facility, since the regulations do change from time to time.

Individual tumour types

High-grade gliomas

Pathology and clinical features

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the commonest primary CNS tumour in adults (see Figure 30.2). GBMs and grade III gliomas are collectively known as high-grade gliomas (HGGs). The major problems with high-grade gliomas are: