and Jurgen J. Fütterer2, 3

(1)

Department of Radiological Sciences, Oncology and Pathology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

(2)

Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

(3)

MIRA Institute for Biomedical Technology and Technical Medicine, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

Ureter, Circumcaval

Occasionally, an abnormally positioned IVC or a periureteric venous ring at the level of the third or fourth lumbar vertebral body medially displaces the right ureter. This abnormality, termed the circumcaval (or retrocaval) ureter, occurs with a frequency of approximately 0.1 %.

It results from anomalous development of the infrarenal vena cava.

In general, patients are asymptomatic. Symptoms (secondary to obstruction), when present, usually appear late.

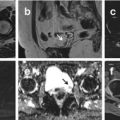

CT and MRI can be used to identify a circumcaval ureter if the right ureter partially encircles the inferior cava, passing first posteriorly and then medially to the IVC. Lateral positioning of the upper abdominal IVC in relation to the right ureter without an identifiable retrocaval component of the ureter, although seen in all patients with circumcaval ureters, is usually a normal variant (6 % of the general population).

Ureter, Ectopic

The incidence of ureteral ectopia is 1:1,900. It is most common in female with a marked prevalence (female:male of 5–6:1). Around 10 % of ureteral ectopias are bilateral.

An ectopic ureter is one that drains in an abnormal location (outside the posterolateral angle of the trigone) either within the bladder (intravesical) or extravesically. Vesicoureteric reflux is often associated, although the condition may be asymptomatic. Ectopic ureter, however, more commonly refers to the extravesical form and is clinically more important than the intravesical type.

Extravesical ureteral ectopia in females is associated with a duplicated system in at least 85 % of cases and affects the upper pole ureter in practically all cases. The ectopic ureter may end in the urethra or in the vestibule or, less commonly, in the vagina.

Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice and often is diagnostic, particularly when the anomalous ureter is dilated. The course of this ureter often may be followed down to and beyond the bladder.

Diagnosis can be even more difficult when the kidney itself is ectopic. MR urography is indicated in the nonfunctioning kidney. Delayed contrast-enhanced CT with thin sections through the kidneys, coronal T1-weighted MRI, and MR urography are the most sensitive modalities for identifying an occult ectopic ureter.

Ureter, Neoplasm of

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) accounts for about 93 % of ureteral neoplasms. Ureteral TCC, like bladder cancer, is more common in men than in women (male–female ratio, 2:1), and the incidence peaks in the seventh decade of life. TCCs of the ureter are most frequently found in the distal ureter (±70 %).

Upper tract TCCs are histologically and cytologically similar to bladder TCCs.

Hematuria is present at diagnosis in 70–95 % of patients. Obstruction of the ureter or ureteropelvic junction due to a tumor mass causes flank pain in 8–40 % of cases. Other urinary tract symptoms, such as those associated with bladder irritation, and constitutional symptoms occur in less than 10 % of cases. The physical examination is usually unremarkable. In rare cases, a flank mass, caused either by the tumor or associated hydronephrosis, may be palpated.

Hydroureteronephrosis is a common finding in CT. In some cases, the tumor can manifest as a mass of solid tissue (≥5 cm) with an attenuation value above urine in baseline images or more commonly as a filling defect or wall thickening in the excretory phase. Other useful CT findings for the identification of ureteric tumors are eccentric or concentric thickening of the ureteric walls, lumen stricture, and invasion of the adjacent structures (wall thickening and enhancement together with periureteric fat stranding are especially indicative of extramural tumor spread).

On MR urography, the lesion appears as an intraluminal filling defect (with consequent dilatation of the collecting system proximally) or nonobstructive. This is useful in differential diagnosis with obstructive calculi. In addition, TCC typically appears as an irregular intraluminal defect, whereas a calculus displays regular and well-defined margins. The differential diagnosis between a tumor and a small stone can nonetheless be challenging. In baseline sequences indeed, TCC has signal intensity similar to that of the psoas muscle in T1-weighted images and slightly higher in T2. In this case, paramagnetic contrast medium, which should produce at least slight enhancement of TCC, is not always helpful.

Ureteral Bud, Atresia of

Atresia of the ureteral bud at or below the ureteropelvic junction results in a severely dysplastic, nonfunctioning, cystic kidney.

The diagnosis is usually easily established on the basis of characteristic imaging findings at ultrasound and renal diuretic or cortical scintigraphy of a nonfunctioning kidney that is replaced by multiple noncommunicating cysts with no residual normal-appearing parenchyma.

At CT and MRI, the kidney is shown to be entirely replaced by multiple cysts of different sizes that are separated by a small amount of nonfunctioning, dysplastic parenchyma. In most patients with a multicystic dysplastic kidney, the fluid within the cysts is gradually absorbed and the kidney progressively decreases in size until it is no longer identifiable at ultrasound. In patients who have severe hypertension or other signs or symptoms suggestive of an occult, dysplastic kidney, MRI has been used to identify the tiny offending dysplastic remnant.

Urinoma

Continued leakage of urine from the collecting system in the presence of urinary obstruction may lead to an encapsulated retroperitoneal urine collection called a urinoma. Urinomas may be associated with ureteropelvic junction obstruction; retroperitoneal fibrosis; retroperitoneal malignancy; cancer of the renal pelvis, ureter, or bladder; and a variety of conditions that cause bladder outlet obstruction. Urinomas may also occur in patients who have experienced blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma, renal surgery, or percutaneous procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree