Fig. 3.1

Sites of free intraperitoneal air in the abdomen on US examination (Modified from Beyer and Modder [21])

3.2.1 US of Pneumoperitoneum

Free air in abdominal cavity can give direct or indirect signs. The main US signs of the presence of pneumoperitoneum include strong reverberation anterior to the liver surface, the shifting phenomenon, and the enhancement of the peritoneal stripe. The indirect signs are the presence of intraperitoneal free fluid and the decreased bowel motility.

3.2.1.1 Reverberations

Air is a medium posing high resistance and impermeability to ultrasound waves, making it a strong reflector. Free air can be visualized as horizontal or vertical reverberations originating in the peritoneum and extending to the lower edge of the monitor. The reverberation echo, generated by an air structure, was well described by Linchenstein [8]. It consists in a succession of roughly horizontal (or slightly curved) lines that generate a striped pattern, alternating dark and clear lines at regular intervals. They can be large or very narrow. The reverberation echo hides the information below, as does an acoustic shadow. Larger air collections make bright, highly echogenic lines with distal reverberation and shadowing artifacts (Fig. 3.2). Smaller air bubbles can appear as bright punctuate foci with or without ring-down artifacts (Fig. 3.3).

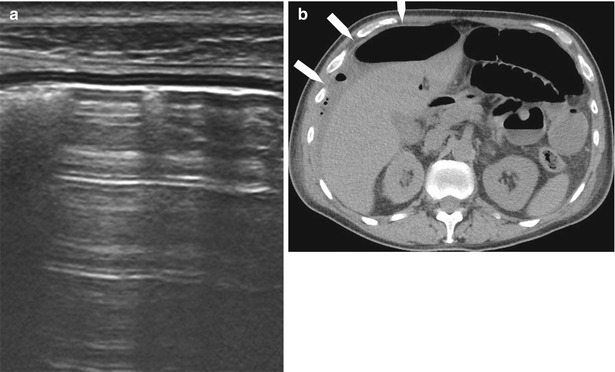

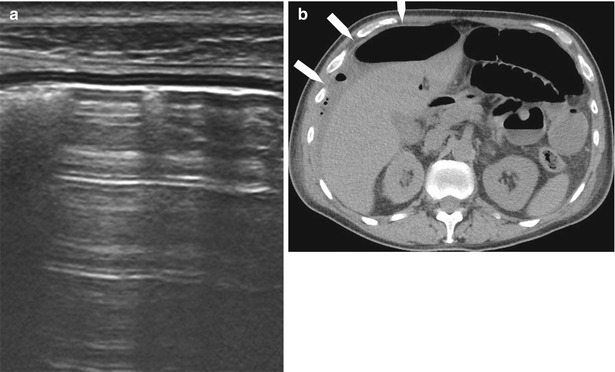

Fig. 3.2

Sagittal sonographic section of the right hypochondrium using a linear probe showing reverberation artifacts which obscure the right lobe of the liver (a). Computed tomography confirms the large amount of air superficial to the liver (b, white arrows). At laparotomy, the patient had perforated peptic ulcer

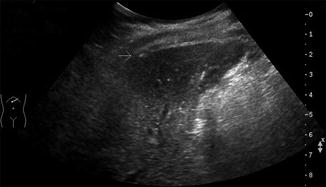

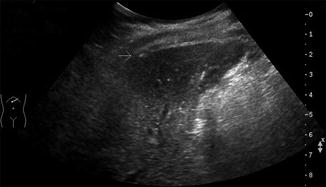

Fig. 3.3

Sagital sonographic section of the right hypochondrium using a curvilinear probe. Small air bubble anterior to the liver causing ring-down artifact (white arrows). This patient presented with normal vital signs had moderate abdominal pain due to perforated diverticulitis.

3.2.1.2 Shifting Phenomenon

Reverberation is not specific for pneumoperitoneum unless it is possible to demonstrate the “shifting” of air in the cavity when the patient was repositioned. It is therefore needed to move the patient on the left semilateral decubitus position observing the shifting of the air in the space between peritoneum and liver or in the hepatorenal space. Excessive gas in an abscess can mimic the shifting phenomenon. For this reason, Karahan and colleagues proposed an original method for the detection of pneumoperitoneum [9]. While the patient is in the supine position, if the reverberation artifact is visible, a slight pressure is applied to the abdominal wall using the probe. During this maneuver, the free intraperitoneal air is expelled from the region anterior to the liver to other parts of the peritoneal cavity, and consequently, the reverberation artifact became much less prominent. Conversely, when the pressure on the probe is released, maintaining the contact with the skin surface, the free gas return to the epigastric region and the artifact echo pattern became more prominent. On real-time US examination, repetition of this maneuver appears like the opening and closing of scissors, leading to the term “scissors maneuver.” The diagnostic accuracy values in the diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum obtained by the authors with the adding of this maneuver was very high, and they reported a sensitivity of 94 %, specificity of 100 %, PPV of 100 %, and NPV of 98 %.

3.2.1.3 Peritoneal Stripe

This finding was first described by Muradali et al. [10], and it was termed the “peritoneal stripe.” Under an animal experimental model, they were able to demonstrate that tiny bubbles of free air produced focal enhancement and apparent thickening of the peritoneal stripe with or without multiple reflection artifacts, depending on the amount of the peritoneal air. In the cases of air within the intestinal bowel, overlying peritoneal stripe was normal, whereas in the cases of extraluminal (intraperitoneal) air, the peritoneal stripe was thickened. The animal model was than demonstrated in nine patients who underwent laparoscopy, and it was documented for all four quadrants of the abdomen. The enhanced peritoneal stripe indicates free intraperitoneal air and permits its differentiation from intraluminal bowel gas (Fig. 3.4). In the US imaging of the abdomen, it is possible to identify a single or a double thin echogenic line between the anterior abdominal wall and the anterior liver surface.

Fig. 3.4

Sagittal sonographic section of the right hypochondrium with curvilinear probe. Enhanced peritoneal stripe (white arrows)

Intraperitoneal free fluid and decreased bowel motility are indirect signs, but in the adequate clinical context can help in the diagnosis [11]. Peritonitis caused by gastrointestinal perforation leads to a paralytic or adynamic ileus, a condition characterized by gas-fluid stasis, with a reduction in intestinal movement [12].

3.3 Causes of Bowel Perforation

The most common causes of gastrointestinal perforation are as follows:

Peptic ulcer

Appendicitis

Sigmoid diverticulitis

Bowel malignancy

Crohn’s disease

Sharp foreign body

One of the hallmarks of bowel perforation useful for identification of the site of the perforation is the inflamed fat, like in appendicitis and diverticulitis. “Inflamed fat” represents the defense mechanism of omentum and mesentery to stop the bowel perforation. Sometimes this mechanism is effective; sometimes it is less effective, and an open perforation can lead to the surgery treatment. Whether this process is going to be successful (and a nonoperative management can be indicated) cannot be judged from the imaging findings alone, and a combination of clinical and imaging findings needs to be considered.

Peptic ulcer. Uncomplicated duodenal ulcer is becoming quite rare, since most symptomatic patients have already been treated with proton pump inhibitors before any test is done. Pneumoperitoneum can sometimes be visualized by US: small amount of air with fluid can be visualized in the falciform ligament or medially to the gallbladder wall (Fig. 3.5).

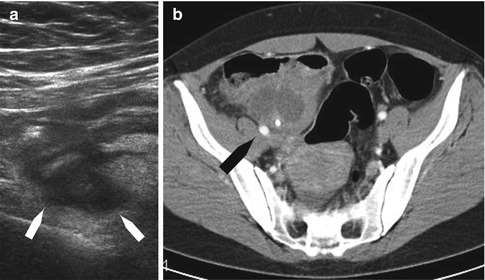

Fig. 3.5

Pneumoperitoneum due to peptic ulcer perforation: small amount of air visualized in the falciform ligament medially to the gallbladder wall (black arrows)

Appendicitis. Appendiceal perforation is a common complication of acute appendicitis. The criteria for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis by sonography are well established: identification of a noncompressible blind-ending structure in the right lower quadrant with an outer diameter of greater than 6 mm. A small quantity of periappendiceal fluid is often present and aspecific. It may be present in both nonperforated and perforated appendicitis and in many other conditions, both surgical and nonsurgical. A large quantity of fluid in the presence of an inflamed appendix may represent pus from perforated appendicitis and then is usually accompanied by paralytic ileus [13]. In case of perforation, an appendiceal abscess can be visible as a circumscribed collection, walled off by omentum, mesentery, and bowel (Fig. 3.6).