Summary of Key Points

- •

Sonography is the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of the myometrium, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reserved as a problem-solving technique.

- •

Many müllerian duct anomalies can be accurately diagnosed with sonography, and three-dimensional (3D) imaging of the fundal contour is diagnostic in differentiating the bicornuate uterus (>1 cm fundal cleft between the two horns) and the septate uterus.

- •

Adenomyosis presents most commonly in middle-aged multiparous women with uterine tenderness, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia and most commonly appears on ultrasound images as an ill-defined or poorly marginated area within the myometrium or thickening of the hypoechoic subendometrial halo. The most specific findings are myometrial cysts and echogenic linear or nodular extension of the endometrium into the subjacent myometrium.

- •

Leiomyoma is the most common uterine neoplasm. Symptoms are primarily related to location and size. Although most leiomyomas are sharply marginated, well-circumscribed hypoechoic masses, leiomyomas may be isoechoic or echogenic relative to the myometrium.

- •

There is overlap in the sonographic and MRI appearance of leiomyomas and adenomyosis/adenomyomas, and the entities may coexist.

- •

Lipoleiomyomas are typically extremely echogenic and sharply marginated with posterior attenuation.

- •

Leiomyosarcomas may be difficult to differentiate from degenerating leiomyomas on both sonography and MRI.

- •

Patients with gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) most commonly present with an echogenic endometrial mass containing numerous small cysts and demonstrating increased vascularity. Fetal parts may be seen in partial moles or coexistent twin pregnancy. Myometrial invasion can be seen with persistent disease or choriocarcinomas, but on imaging may be difficult to differentiate from increased vascularity and “pseudoinvasion” from the placental bed, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), or retained products of conception (RPOC).

- •

Uterine AVMs are most often traumatic in origin but may also be congenital or diagnosed in the setting of persistent GTD and RPOC.

- •

Sonography may be helpful in the diagnosis of endocervical polyps. However, the sonographic appearances of cervical leiomyoma and carcinoma overlap.

Sonography is clearly the modality of choice for imaging the female pelvis, including the uterus and adnexal structures. In our clinical laboratory, a combination of transabdominal pelvic scanning as well as transvaginal examination is performed in most patients. This approach allows the examiner to evaluate the true pelvis in its entirety with a wide field of view on transabdominal imaging, as well as to assess specific structures using high-resolution images obtained on transvaginal scanning. Primary evaluation with ultrasound in conjunction with clinical information is often sufficient for diagnosis and patient management and will help optimize recommendations for further imaging as necessary. When ultrasound evaluation fails to provide adequate information or does not answer the clinical question, further evaluation with MRI, computed tomography (CT) scanning, hysterography, or saline infusion sonography (SIS) can be performed. MRI of the uterus is discussed in detail in Chapter 36 .

In this chapter, we discuss ultrasound evaluation of the normal uterus, anatomic variants, and benign and malignant conditions. A discussion of the normal and abnormal endometrium in the patient who presents with abnormal uterine bleeding is presented in Chapter 27 .

Imaging

Guidelines

The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) guidelines for imaging of the uterus have been developed to assist physicians in performing sonographic studies of the female pelvis. Knowing the potential, but also the limitations, of ultrasound helps us to maximize the probability of detecting most significant abnormalities. As with any clinical test, ultrasound examination of the pelvis should be performed only if there is a valid clinical reason. Following the AIUM guidelines, the indications for pelvic sonography include, but are not limited to, the following:

- 1.

Evaluation of pelvic pain

- 2.

Evaluation of pelvic masses

- 3.

Evaluation of endocrine abnormalities, including polycystic ovaries

- 4.

Evaluation of dysmenorrhea (painful menses)

- 5.

Evaluation of amenorrhea

- 6.

Evaluation of abnormal bleeding

- 7.

Evaluation of delayed menses

- 8.

Follow-up of a previously detected abnormality

- 9.

Evaluation, monitoring, and/or treatment of infertility patients

- 10.

Evaluation in the presence of a limited clinical examination of the pelvis

- 11.

Evaluation for signs or symptoms of pelvic infection

- 12.

Further characterization of a pelvic abnormality noted on another imaging study

- 13.

Evaluation of congenital uterine and lower genital tract anomalies

- 14.

Evaluation of excessive bleeding, pain, or signs of infection after pelvic surgery, delivery, or abortion

- 15.

Localization of an intrauterine contraceptive device

- 16.

Screening for malignancy in high-risk patients

- 17.

Evaluation of incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse

- 18.

Guidance for interventional or surgical procedures; and

- 19.

Preoperative and postoperative evaluation of pelvic structures

Techniques

All relevant anatomic structures in the pelvis should be identified first by transabdominal technique, and then more detailed evaluation of the deep pelvic structures should be performed using the transvaginal technique. In specific situations when transvaginal evaluation cannot be performed or tolerated, transrectal or transperineal evaluation can be very useful.

The transducer should be selected to operate at the highest clinically appropriate frequency that will allow adequate visualization of deep pelvic structures. For transabdominal evaluation, a 3.5-MHz or higher transducer is employed. Curved linear array transducers, as well as sector transducers with a smaller footprint, are most often employed. For transabdominal evaluation, the bladder should be adequately distended to displace bowel superiorly out of the true pelvis and to provide an acoustic window to visualize the uterus and adnexa ( Fig. 28-1 ).

For transvaginal evaluation, the urinary bladder should be emptied and the patient placed in a comfortable position but with her pelvis tilted either with the use of stirrups or by the placement of padding under the patient to elevate the hips. The patient or the sonographer, depending upon the patient’s preference, may introduce the vaginal transducer with real-time monitoring. For transvaginal evaluation, the AIUM recommends using probe frequencies of 5 MHz or higher ( Fig. 28-2 ). If a male sonologist is performing the examination, a female member of the staff should be present as a chaperone. However, in some clinical situations, a chaperone is helpful and recommended even for a female sonologist.

The vagina, uterus, and the urinary bladder are used as reference points for identification of the remaining normal and abnormal pelvic structures. The uterine size, shape, and orientation should be assessed and documented in both sagittal (long-axis) and transverse (axial or short-axis) planes. The endometrium, myometrium, and cervix should be carefully evaluated, and their appearance documented. The uterine length is measured in long axis from the fundus to the external os of the cervix, and the anteroposterior dimension is measured on the same image perpendicular to the long axis. The width is measured on either a transaxial or coronal imaging plane. If the volume of the uterine corpus is assessed, the cervical component should be excluded. Myometrial masses and contour abnormalities should be recorded in two different planes and their locations recorded. Assessment of the endometrium is performed primarily in the sagittal (or sometimes coronal) plane. Variations of the normal appearance of the endometrium during different phases of the menstrual cycle and with hormonal supplementation should be considered ( Fig. 28-3 ) and have been described in detail in preceding chapters. Doppler evaluation of the uterus and endometrium can be of added value. 3D imaging is increasingly available and can also provide valuable additional information, particularly by providing a coronal image of the fundal contour of the uterus in women with suspected uterine congenital malformations and to localize leiomyomas.

SIS, or as it is often referred to, sonohysterography, is an innovative technique used to evaluate a variety of endometrial and myometrial processes that involve the endometrial canal. The most common indications for SIS include, but are not limited to, evaluation of the following:

- 1.

Abnormal uterine bleeding

- 2.

Uterine cavity, especially with regard to uterine leiomyomas, polyps, and synechiae

- 3.

Abnormalities detected on transvaginal sonography, including focal or diffuse endometrial or intracavitary abnormalities

- 4.

Congenital abnormalities of the uterus

- 5.

Infertility

- 6.

Recurrent pregnancy loss

At our institution, we perform a preliminary transabdominal and transvaginal sonogram before SIS. After the procedure is explained to the patient, the external os is cleansed before catheterization of the cervical canal using aseptic technique. A sonohysterography catheter (flushed with saline to remove any air bubbles) is then advanced into the endometrial canal. Once in the endometrial canal, the balloon is inflated (preferably with saline rather than air to avoid shadowing) so that the catheter does not become dislodged. However, some clinicians prefer to use a catheter without a balloon. The speculum is removed, and the transvaginal probe is reinserted adjacent to the catheter. Under ultrasound guidance, the balloon is gently retracted to occlude the internal os. Sterile saline should be administered under real-time sonography. The amount of saline introduced is variable, often between 5 and 30 mL. Normal anatomy and abnormal findings should be documented in two separate imaging planes using a high-frequency transvaginal probe, and the endometrium should be fully evaluated from one cornua to the other ( Fig. 28-4 ). Additional techniques such as color Doppler and 3D imaging may be helpful in evaluating both normal and abnormal findings.

Anatomy

The uterus is a hollow organ in which the myometrium is firmly adherent to a thin internal layer of endometrium. Externally the uterus is embedded between the two layers of the broad ligament. Anatomically, the uterus lies between the bladder anteriorly and the rectosigmoid colon posteriorly. The uterus is divided into two major parts, the body or corpus and the cervix. The most superior aspect of the uterus is referred to as the fundus and the area where the fallopian tubes enter into the uterus is referred to as the cornua. Anterior to the fallopian tubes are the round ligaments, one on each side, which extend anterolaterally, coursing through the inguinal canals and inserting onto the fascia of the labia majora. The uterus has a dual arterial blood supply. The majority of the blood supply comes from the uterine arteries, which arise from the internal iliac arteries, and a minor source of blood supply is the ovarian arteries.

The uterus is most often anteverted and anteflexed ( Fig. 28-5 ), but it may also be retroflexed ( Fig. 28-6 ) or retroverted ( Fig. 28-7 ). Descriptions of flexion refer to the relationship of the body of the uterus to the cervix at the level of the internal os (usually the angle is about 270 degrees), whereas version refers to the cervical relationship to the vagina. The cervix of the uterus is fixed in the midline. However, the body of the uterus can be mobile, and uterine position and orientation may change with varying degrees of bladder and rectal distention. Retroversion and retroflexion are not infrequent in the nongravid state. In such cases the fundus of the uterus is positioned in the sacral hollow. During pregnancy the uterus enlarges and physiologically undergoes reduction by the 14th to 16th weeks of gestation. The fundus of the uterus then rises into the false pelvis. If this fails to happen, the uterus becomes “trapped” in the sacral hollow, often referred to as “incarcerated.” In cases of incarceration of the uterus, the cervix is drawn upward either against or above the symphysis pubis, resulting in distortion of the bladder and urethra as the gestation progresses. The posteriorly positioned fundus can cause pressure on the rectum. Typically, patients present between the 13th to 17th weeks of pregnancy with symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction. A history of multiple trips to the emergency room for bladder outlet obstruction should raise suspicion.

A constellation of three findings on sonography is diagnostic of an incarcerated uterus:

- 1.

The pregnancy is deep within the cul-de-sac.

- 2.

The maternal urinary bladder lies anterior rather than inferior to the uterine corpus and marked bladder distention is noted.

- 3.

A soft tissue structure (the cervix) is seen between the bladder and pregnancy. This appearance can be misconstrued as an empty uterus associated with an ectopic or abdominal pregnancy.

The shape and size of the uterus vary throughout life, affected mostly by hormonal status. The mean measurement of the prepubertal uterus is 2.8 cm in length and 0.8 cm in maximum anteroposterior dimension, with the cervix accounting for two thirds of the total length and contributing to the pear-shaped appearance ( Fig. 28-9 ). It is important to remember that in the immediate postdelivery state, the neonatal uterus can be slightly larger owing to the effects of residual maternal hormones. For the same reason, the echogenic endometrium is well seen and a small amount of fluid can be present in the endometrial cavity.

From birth until 4 years of age, the uterus decreases in size. At approximately 8 years of age, the uterus starts to grow preferentially in the fundus. The uterus continues to grow for several years after menarche until it reaches the mean dimensions of a reproductive age uterus, which are approximately 7 cm long and 4 cm wide. Parity increases the size of the uterus, with a multiparous uterus measuring approximately 8.5 cm by 5.5 cm.

Following menopause, the uterus decreases in size. The decrease in size is related to the number of years since menopause, although the reduction in size is believed to be most rapid during the first decade following menopause. The length of the normal postmenopausal uterus has been reported to range from 3.5 to 6.5 cm and the anteroposterior dimension from 1.2 to 1.8 cm.

The normal myometrium is composed of three layers. The innermost layer, immediately subjacent to the endometrium, is the thinnest and is relatively compact histologically. This layer is also both hypovascular and hypoechoic when compared to the echogenic endometrium and surrounding middle layer of the myometrium. This layer is often referred to as the subendometrial halo and may not always be visualized sonographically. Sometimes, small extremely echogenic foci, usually less than a few millimeters in size and without posterior shadowing, are seen in the inner myometrium at the endometrial/myometrial interface. These foci are thought to represent dystrophic calcifications due to previous intrauterine instrumentation and have no clinical significance. The middle or intermediate layer lies between the subendometrial halo and the arcuate vessels. This is the thickest myometrial layer and is normally uniform and intermediate in echogenicity. The outer layer lies peripheral to or above the arcuate vessels. This layer is relatively thin and slightly less echogenic compared to the intermediate layer in most patients. The cervix is measured from the internal os, identified by narrowing or “waisting” of the uterus at the junction of the lower uterine segment with the cervix to the lips of the external os, which can be seen to project into the lumen of the vagina. The central endocervical canal is echogenic and continuous with the endometrium. The surrounding fibrous cervical stroma is quite hypoechoic and is continuous with the subendometrial halo, if present. The outer cervical muscular layer is continuous with and similar in echogenicity to the intermediate layer of the myometrium ( Fig. 28-10 ).

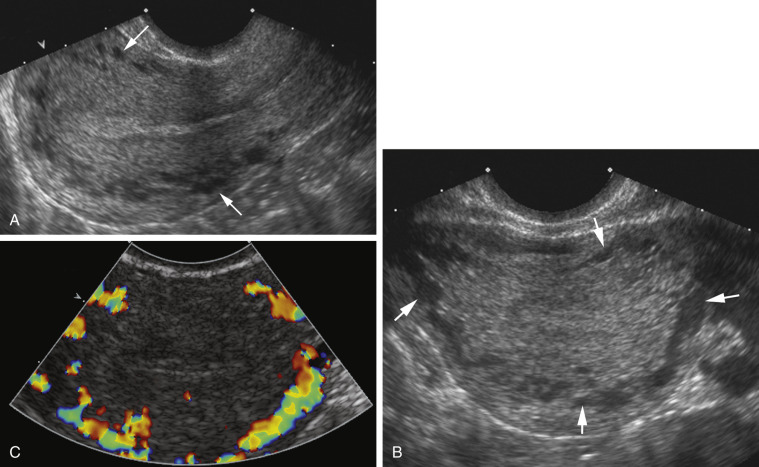

The arcuate vessels separate the outer layer from the intermediate layer of the myometrium. The arcuate veins are larger than the arcuate arteries and are potentially compressible with excessive probe or manual pressure. The arcuate vessels (particularly the veins) can be prominent and mimic cystic changes. This potential misinterpretation can easily be clarified by using color Doppler imaging ( Fig. 28-11 ). The arcuate arteries branch into radial arteries that penetrate the intermediate layer and reach the level of the inner layer. The arcuate arteries may calcify in postmenopausal women, and this process can be seen earlier in diabetic patients. This change is considered part of the normal aging process ( Fig. 28-12 ).

Congenital Malformations

The incidence of congenital müllerian duct anomalies is estimated to be approximately 0.5% in the general population. However, they are more often diagnosed during workup for infertility, frequent miscarriages, or menstrual disorders. Embryologically, the two paired müllerian ducts ultimately develop into the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and the upper two thirds to four fifths of the vagina. The lower one fifth to one third of the vagina and the ovaries have a separate embryologic origin. Uterine malformations arise from three different causes: failure of development of the müllerian ducts, failure of fusion of the müllerian ducts, or failure of resorption of the median septum ( Fig. 28-13 ). There is a strong association of upper urinary tract anomalies with congenital uterine malformations. These anomalies have been reported to be most common in patients with hypoplasia or agenesis, occurring in as many as 30% to 40% of patients. Ispilateral renal agenesis and ectopic pelvic kidney are most common.

Early developmental failure of the müllerian ducts can result in agenesis or hypoplasia of the proximal two thirds of the vagina, cervix, and uterus, being part of the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. This syndrome is an extreme form of müllerian duct anomaly with complete agenesis of the proximal vagina and anomalous cervix and uterus, and patients usually present in early puberty with primary amenorrhea. The ovaries are normal but the fallopian tubes may be closed and the uterus is often anomalous. The vaginal aplasia can vary from complete absence to a blind-ending pouch. Associated renal anomalies are common, in particular absence or ectopia of the kidney. Because there can be subtypes of MRKH syndrome as well as overlap with other rare müllerian duct hypoplasia/aplasia syndromes, it is important to describe findings rather than trying to fit them into a strict category. MRI is usually the most helpful imaging modality for diagnosis of this entity given the complex spectrum of findings. Most important is communication with the clinical team regarding the relevance of findings and preoperative planning.

Arrested development of the müllerian ducts can also cause uterine agenesis or hypoplasia. This abnormality may present as vaginal, cervical, fundal, tubal, or combined agenesis or hypoplasia.

Complete or partial agenesis of a unilateral müllerian duct leads to development of a unicornuate uterus with a single fallopian tube ( Fig. 28-13 ). The unicornuate uterus accounts for approximately 20% of all müllerian duct anomalies. In some cases, a rudimentary horn on the opposite side can be seen. This rudimentary horn may or may not communicate with the endometrial cavity in the normal side. If there is no communication between the endometrial cavities of the rudimentary and normal horns, retrograde menstruation may occur, leading to the development of endometriosis. Ectopic pregnancies may also rarely occur in the rudimentary horn. Such ectopic pregnancies can lead to massive hemorrhage as they can grow to relatively large size before rupturing. Therefore, if a rudimentary horn is documented, surgical resection is usually recommended. The poorest fetal survival among all müllerian duct anomalies has been reported with the unicornuate uterus. Spontaneous abortion has been reported to occur in 34%, preterm labor in 20%, and intrauterine demise in 10%. The live birth rate is estimated to be only 50%. The unicornuate uterus seems to be the most difficult müllerian duct anomaly to confidently diagnose on sonography because it can be confused and misdiagnosed as a small uterus. Looking for the contralateral rudimentary horn, which can be filled with blood, may sometimes help. The rudimentary horn may have a distended and dystrophic appearance and should not be mistaken for an adnexal mass. MRI is considered the study of choice in resolving these complicated situations. Recently 3D ultrasound has been reported to be useful in diagnosis, allowing visualization on the coronal imaging plane of a single asymmetric endometrial cavity that is laterally deviated, with or without a rudimentary horn. Forty percent of cases are reported to have renal anomalies, typically ipsilateral to the rudimentary horn, most often renal agenesis or pelvic kidney.

Complete failure of fusion of the müllerian ducts leads to development of two separate uteri, each with its own cervix, termed uterus didelphys ( Fig. 28-13 ). This is a relatively rare anomaly accounting for fewer than 5% of all müllerian duct anomalies. The endometrial cavities of each hemiuterus do not communicate. A longitudinal or oblique vaginal septum is common, but not always present. An oblique septum may be obstructive and such patients will present with hematocolpos, dysmenorrhea, pelvic mass, vaginal discharge, or pelvic pain. The vaginal septum may also lead to dyspareunia and even rarely vaginal dystocia during vaginal delivery. If no obstruction is present, most patients are asymptomatic and uterus didelphys is an incidental finding. Patients with uterus didelphys usually successfully carry pregnancies to term, and infertility is an uncommon presentation. On ultrasound images, the two widely separated fundal horns with a deep fundal cleft, two uterine cavities, and two separate cervices can be identified. However, the vaginal septum is better evaluated on physical examination and with MRI or CT ( Fig. 28-14 ), although occasionally 3D ultrasound imaging may be helpful. Unilateral renal agenesis is often present, particularly in the setting of obstructed uterus didelphys.

A rare syndrome that can be seen in the setting of uterus didelphys is obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA); some cases do not fit the classic definition. An absent kidney in the expected anatomic location should trigger a search for an ectopic or possibly a dysplastic/atrophic kidney. If obstructed hemivagina is seen, this finding should also trigger a search for possible ectopic insertion of a ureter. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis syndrome should be redefined as ipsilateral renal anomalies: cases of symptomatic atrophic and dysplastic kidney with ectopic ureter to obstructed hemivagina.

Partial fusion of the two müllerian ducts with incomplete fusion at the fundus leads to formation of a bicornuate uterus and a single cervix ( Fig. 28-13 ). The bicornuate uterus is estimated to account for approximately 10% of all müllerian duct anomalies. The fundal contour of the bicornuate uterus is concave, and the two horns are divergent. MRI criteria based on this appearance are an intercornual distance greater than 4 cm and a fundal cleft depth 1 cm or more between the horns. Patients with bicornuate uterus have few reported obstetric problems, and most cases are discovered incidentally. However, an increased incidence of cervical incompetence has been reported. Decreased size of the uterine cavity has also been reported to be associated with poor fetal outcome. Sonographically, in a bicornuate uterus, the endometrial cavities are widely separated, and a deep indentation in the fundal contour is obvious. Imaging of the fundal contour requires obtaining an image in a coronal plane, which is often easiest with transabdominal pelvic ultrasound if the uterus is anteverted and anteflexed or with 3D transvaginal imaging. MRI is often recommended for definitive diagnosis. The bicornuate uterus should be distinguished from a uterine didelphys, and a single cervix should be documented to confirm the diagnosis of a bicornuate uterus ( Fig. 28-15 ). However, if two endocervical canals are present, such as in the bicornuate bicollis uterus, identification of a vaginal septum can be the only way to discriminate between a bicornuate bicollis and didelphys uterus. Unfortunately, one fourth of bicornuate uterus cases have been reported to have a vaginal septum as well, which makes them indistinguishable from didelphys. MRI is the optimal imaging technique for evaluation of vaginal septa. Often in these complex cases with overlapping appearances, it is best to describe what is seen on MRI rather than to attempt to categorize.

Failure of resorption of the septum after complete fusion of the müllerian ducts leads to formation of a septate uterus ( Fig. 28-13 ), which is the most common type of müllerian duct anomaly, accounting for close to 55%. The fundal contour between the two endometrial cavities is convex, flat, or indented less than 1 cm. The septum may be partial (if partial resorption has occurred) or complete, extending to the internal cervical os and sometimes through the cervix to the external os. The septum can contain fibrous or myometrial tissue. The endometrial cavities are typically symmetric. Many women with a septate uterus experience repeated miscarriages, usually in the first trimester, with a reported incidence of miscarriage of 65% and an incidence of premature birth of nearly 20%. Confirming this type of anomaly is clinically important because metroplasty is reported to improve fetal survival. Metroplasty may be performed hysteroscopically in women with a septate uterus, whereas surgical repair/resection in a patient with a bicornuate uterus must be performed transabdominally, although surgical correction is less often required. On sonography, the smooth fundal contour (either convex, flat, or indented <1 cm) is diagnostic, but requires obtaining an image of the fundus in the coronal plane, which can be difficult on transvaginal imaging and is more easily accomplished with 3D imaging or occasionally with transabdominal imaging if the uterus is anteverted and anteflexed. There is less divergence between the two endometrial cavities, which are usually separated by a very thin septum ( Fig. 28-16 ). The septum can extend all the way to the external os or even upper vagina. If the septum does not extend to the internal cervical os, it should be described as a partial septate uterus. Because of superior multiplanar imaging capability, MRI is generally considered the most definitive imaging modality for distinguishing a septate from a bicornuate uterus as obtaining a true coronal image through the uterine fundus is routinely possible on MRI. It is the depth of the fundal notch between the two uterine horns that is the primary diagnostic criterion rather than the composition of the septum. Evaluation of associated renal anomalies and for the presence of a vaginal septum is also easily accomplished with MRI. However, advances in the use of 3D ultrasound have made it possible to visualize the fundal contour in many patients, and 3D sonography is replacing MRI in some centers for at least initial evaluation of uterine congenital anomalies.