9 Ultrasound of the paediatric abdomen

Introduction

Techniques

Hepato-biliary pathology

Cystic fibrosis

Pancreatic insufficiency, requiring enzyme supplements, is a feature of cystic fibrosis, with gradual fatty replacement and subsequent fibrosis of pancreatic tissue, resulting in increased echogenicity of the pancreatic parenchyma. The pancreas is generally reduced in size. Cysts, calcification and ductal dilatation may also be found.1 Advances in the management of pulmonary problems associated with cystic fibrosis have led to longer survival and a subsequent increase in the prevalence of chronic liver disease. Annual ultrasound examination is recommended as sonographic changes may be identified in the absence of abnormality on biochemical assessment.2 The liver may be hyperechoic and the texture becomes coarse and nodular as fibrosis develops (Fig. 9.1). Increased periportal echogenicity may be demonstrated. Eventually cirrhosis develops, causing portal hypertension. Assessment of the portal venous system with colour and spectral Doppler is useful, providing a baseline with which to compare progression of the disease.

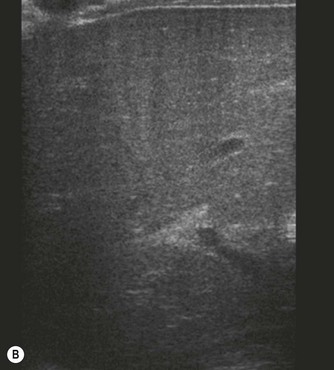

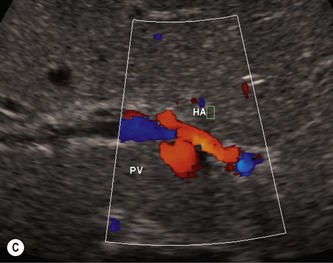

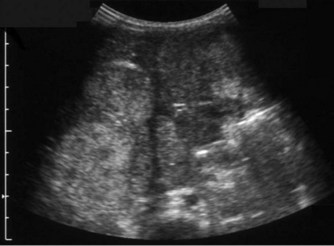

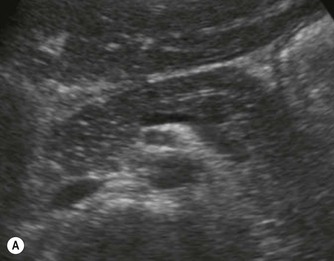

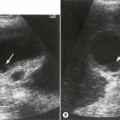

Fig. 9.1 • Cystic fibrosis (CF).

(B) Hyperechoic, coarse pancreas, typical of CF.

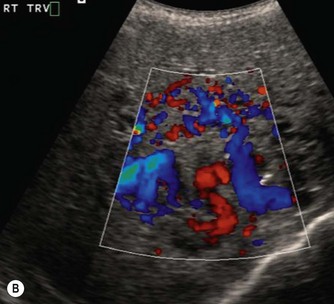

(C) Enlarged spleen caused by portal hypertension in CF.

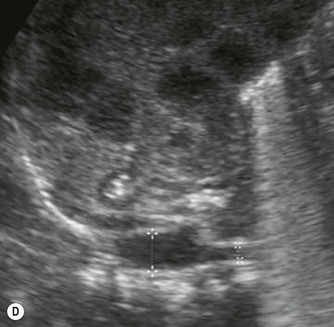

(D) Microgallbladder. The gallbladder is thick walled and small, despite fasting.

The gallbladder is small in up to one third of patients1,3 (Fig. 9.1D). This microgallbladder measures less than 3 × 1 × 1 cm after fasting and is filled with mucus. Up to 10% of patients with cystic fibrosis may have gallstones; cholecystitis and biliary strictures may occur.

Neonatal cholestasis and biliary atresia

Babies who have persistent jaundice beyond 2 weeks of age and any neonate with conjugated jaundice should be investigated to exclude biliary atresia.4 Biliary atresia and neonatal hepatitis are the most common causes of neonatal cholestasis, typically presenting at 1–2 months of age with jaundice, dark urine and pale stools. Early diagnosis of biliary atresia and differentiation from hepatitis and other causes of neonatal cholestasis are crucial to successful treatment. The aetiology of biliary atresia remains unclear but progressive inflammation, destruction and fibrosis of the biliary tree occurs resulting in obliteration of all or part of the bile ducts and gallbladder with the subsequent development biliary cirrhosis.5

The presence or absence of a gallbladder is not a reliable sign of biliary atresia, though detailed ultrasound examination in expert hands has revealed that there are ultrasound features that can help make the diagnosis (Fig. 9.2).6 These include an abnormal gallbladder which may have an irregular wall, abnormal shape or be small. An area of increased echogenicity may be seen anterior to the bifurcation of the portal vein. This is known as the triangular cord sign and represents the fibrotic remnant of the extrahepatic biliary tree. There may be absence of the common bile duct and the intra and extrahepatic biliary tree is not dilated although a cyst is sometimes seen at the porta hepatis. The developing cirrhosis leads rapidly to portal hypertension so there may be hepatosplenomegaly. The hepatic artery can become hypertrophied and appear dominant.

Approximately 10–20% of infants with biliary atresia have associated congenital abnormalities including situs inversus, polysplenia, preduodenal portal vein and interruption of the IVC with azygous continuation, all of which may be detected on sonography. Sonography can also exclude other less frequent causes of neonatal cholestasis such as a congenital choledochal cyst and obstruction to the common bile duct due to bile inspissation where biliary tract dilatation will be noted. The diameter of the normal CBD should not be greater than 2 mm in the infant up to 1-year-old (or 4 mm in children up to 10 years of age).7

Liver biopsy and radioisotope studies are also used to try to differentiate biliary atresia from neonatal hepatitis. Excretion of radionuclide from the liver into the duodenum excludes biliary atresia although a lack of excretion into the duodenum may be seen in both atresia and severe neonatal hepatitis. In some centres MR cholangiography and/or ERCP are used to investigate neonatal jaundice, however, the small duct size and motion sensitivity related to rapid respiratory and heart rate make these investigations challenging.8 In cases where biliary atresia has not been excluded, laparotomy with intraoperative cholangiogram will be necessary to reach a final diagnosis.

Choledochal cyst

Choledochal cysts are congenital dilations of the biliary tree that may present at any age, and can be diagnosed in the fetus during routine obstetric scanning. In the neonate the main presenting feature will be cholestatic jaundice but the classical triad of pain, jaundice and a palpable mass is more likely to be seen in the young adult. Choledochal cysts can be classified into five anatomical types as described by Todani et al.9 The most common form is type 1 which occurs in up to 90% of cases and consists of varying degrees of CBD dilatation over a variable length. In many cases there is an anomalous insertion of the bile duct into the pancreatic duct of Wirsung.

On sonography a well-defined cyst will be identified close to the porta hepatis in continuity with the biliary tree (Fig. 9.3). There may be dilatation of the proximal bile ducts and sludge or calculi may be seen within the cyst. Small choledochal cysts may be seen in association with biliary atresia but in these cases there will be no associated biliary tract dilatation. Further complications of choledochal cysts include: cholangitis, pancreatitis, liver abscess (Fig. 9.3B) and cyst rupture. Definitive diagnosis is made by MR cholangiography although scintigraphy and ERCP may be useful in difficult cases.10

Fig. 9.3 • (A) Large choledochal cyst containing debris seen at the porta hepatis.

(B) Liver abscesses seen in a 10-year-old girl with a choledochal cyst.

Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma

Primary, malignant tumours of the liver are comparatively rare in children and frequently present as a large abdominal mass. Large hepatic tumours may present acutely as a result of haemorrhage. Hepatoblastoma is the commonest primary liver malignancy in childhood, generally occurring in children under 3 years of age and may be associated with predisposing conditions such as Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and children infected with HIV (Fig. 9.4).11 Metastatic spread is most frequent to the lungs, brain and local lymph nodes. HCC is more usually associated with chronic liver disease and tends to develop during the later stage of disease with peak incidences of 4–5 years and 12–14 years. Both tumours are associated with increased levels of serum alpha-fetoprotein.

On ultrasound, these tumours appear solid, heterogeneous and are often large and poorly demarcated from the adjacent liver parenchyma. Areas of necrosis or haemorrhage may be identified in the mass. Occasionally they may be multifocal. Although the two types of tumour are not distinguishable on ultrasound, the clinical history may give a clue and ultrasound guided biopsy can be used to obtain a histological diagnosis. Ultrasound is useful in identifying the extent of the tumour, and when combined with colour flow Doppler imaging, adjacent vascular invasion can be evaluated. CT or MRI complement the ultrasound findings and are essential for staging and assessment of suitability for resection or transplantation.12 Chemotherapy may be used to shrink the tumour prior to surgery.

Other causes of focal liver lesions

Liver metastases may occur from most paediatric malignancies particularly, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and Wilms’ tumour (Fig. 9.13C). Leukaemia and lymphoma may also cause focal defects in the liver. Liver involvement may be manifested by hepatomegaly with normal liver texture, a non-specific sign, or by diffuse coarsened liver texture with or without hepatomegaly.

Haemangioendothelioma and haemangiomas

Vascular tumours account for most benign liver tumours in childhood. Haemangioendotheliomas and haemangiomas are benign tumours whose clinical course, prognosis and treatment are similar. The radiological appearances of these lesions overlap and although there is a histological distinction between them, hepatic tissue is not commonly obtained and either term may be used in clinical practice.13 Infants may be asymptomatic but generally present before the age of 6 months with an abdominal mass, respiratory distress, anaemia and cardiac failure, caused by the shunting of blood from the aorta through the tumour. In rare cases large tumours may bleed spontaneously, resulting in haemoperitoneum. They may present with jaundice and increased transaminase levels and 50% of children also have cutaneous haemangiomas.14

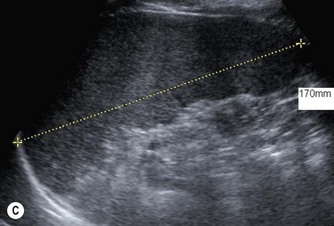

These tumours can be solitary or multiple, of varying echogenicity and may have a complex echotexture due to thrombus, calcifications and internal septations (Fig. 9.5). The vascular nature of these lesions is demonstrated by a large coeliac axis and marked decrease in the size of the aorta below the origin of the coeliac axis (Fig. 9.5D). The main differential diagnosis of multiple haemangioendotheliomas is from metastatic liver disease particularly from disseminated neuroblastoma.

Fig. 9.5 • (A) Large solitary haemangioendothelioma in a 4-week-old girl.

(B) Colour Doppler image demonstrates the highly vascular nature of these lesions.

Pancreas

Normal appearances

The acoustic characteristics of the pancreas vary with age. Pancreatic echogenicity is quite variable and is occasionally hypoechoic in neonates compared with the adult gland. In older children echogenicity is equal to or slightly greater than that of the liver. The pancreas is relatively larger in young children than in adults gradually increasing with age, reaching adult size in late teens.15 The pancreatic duct should not be greater than 2 mm in diameter. The relative hypoechogenicity and relatively larger size of the normal pancreas in childhood should not be misinterpreted as a sign of probable pancreatitis when scanning a child with abdominal pain (Fig. 9.6A).

Pathology of the pancreas

Pancreatic abnormalities are relatively uncommon in childhood. Most ultrasound abnormalities are the result of infiltrative processes associated with other syndromes or diseases (Table 9.1). Focal pancreatic lesions are rare but as with adult practice, the presence of biliary and pancreatic duct dilatation should be treated with suspicion (Fig. 9.6B).

Table 9.1 Paediatric pancreatic abnormalities

| INCREASED ECHOGENICITY | |

|---|---|

| Cystic fibrosis | Fatty replacement of the pancreas, calcifications, ectatic pancreatic duct, coarse texture, cysts |

| Pancreatitis | |

| Haemochromatosis | Pancreatic fibrosis, iron deposition in liver and pancreas |

| FOCAL LESIONS | |

|---|---|

| Cysts | |

| Solid lesions | Primary pancreatic neoplasms are very rare in children |

Urinary tract

Normal appearances

After birth the renal cortex is relatively hyperechoic compared to the adult kidney, in strong contrast to the hypoechoic medullary pyramids. The outline of the kidney is often lobulated due to persistent fetal lobulation. The renal pelvis is relatively hypoechoic, as the fat deposition seen in the adult is not yet present (Fig. 9.7A).

(B) Duplex kidney. The upper moiety is dilated with a thin cortex, the lower moiety is normal.

(D) Renal fusion forming a ‘cake’ shaped solitary kidney in the pelvis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree