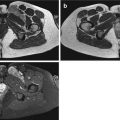

Fig. 19.1

(a, b) Round cell sarcoma (Ewing sarcoma). (a) Pre-chemotherapy axial T2FS MR image. (b) Post-chemotherapy axial T2FS MRI image. These pre- and post-chemotherapy images demonstrate that round cell sarcomas are very chemosensitive. The tumour in (a, black arrow) has significantly reduced as demonstrated in (b, white arrow), after appropriate chemotherapy was given to the patient. This case demonstrates the necessity to subclassify round cell sarcomas if possible

To optimise treatment, USCS should be differentiated from two other spindle-celled sarcomas (monophasic synovial sarcoma and fibrosarcomatous variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP)).

Epithelioid sarcomas can be readily subclassified, and the differential diagnosis of UES is metastatic carcinoma or metastatic melanoma [15]. Once epithelial or melanocytic differentiation has been excluded, diagnosis of an UES can be made.

19.1.1 Epidemiology

USTS accounts for 20 % of all STSs and is the third most common STS subtype [36]. USTSs occur in all ages; however, URCS is more commonly seen in young patients, whereas UPS predominantly occurs in the elderly. USTSs may occur in any location; however, it most commonly occurs in the extremity (lower > upper) [34], followed by the retroperitoneum and trunk. Around 1–5 % of cases have been reported to arise in bone [27]. Male sex predominance (male/female ratio 1.2:1) is reported in literature [25, 27].

The aetiology of USTS is unknown; however, approximately 25 % of USTSs are radiation induced [17, 22]. Two theories have been postulated. The more common is that USTSs represent a common ‘morphologic pattern’, irrespective of its differentiation, rather than a specific type of malignancy. It is suggested that there is a final common pathway of cancer progression, in which tumours become progressively more undifferentiated, resulting in a high-grade USTS [26]. The second theory proposes that undifferentiated sarcomas are the result of transformation of mesenchymal stem cells, rather than the result of the loss of differentiation markers from previously differentiated sarcomas [9, 13, 26].

19.1.2 Clinical Behaviour and Gross Findings

USTS has an aggressive clinical behaviour [18], presenting as a deep-seated, often intramuscular, painless solid mass [30]. Up to 5 % of cases demonstrate extensive haemorrhage, presenting as a fluctuant mass and may be misinterpreted as a haematoma. Tumours can be between 5–15 cm and >20 cm when in the retroperitoneum. Therefore, an underlying malignancy should be excluded in those thought to have spontaneous musculoskeletal haemorrhage or a haematoma out of proportion to the degree of trauma [30]. Macroscopically, USTS has a pseudocapsule and is a pale fleshy mass with internal areas of haemorrhage or necrosis. USTS has a high propensity for local recurrence, with reported rates exceeding 31 % [34] with 30–50 % of patients having metastases at the time of diagnosis [4]. About 90 % of metastases are in the lung [32]. The overall 5-year survival is reported to be between 36 and 50 % [4, 30].

19.1.3 Pathology

USTS can be subdivided according to the cellular morphology into spindle cell morphology, pleomorphic morphology, round cell morphology, epithelioid morphology and not otherwise specified. There is no specific characteristic feature between the subsets apart from their lack of an identifiable line of differentiation [16].

UPS can appear similar to other pleomorphic sarcomas with bizarre multinucleate giant cells [16]. USCS demonstrates a fascicular architecture with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapering nuclei [16]. URCS has a round/oval cellular morphology with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. As mentioned previously, it is important to ensure that a URCS is not in fact an Ewing sarcoma. Little knowledge of UES exists [37], but it closely resembles metastatic carcinoma or melanoma.

In the future, further genomic profiling and identifying chromosomal translocations will enable some of the seemingly undifferentiated sarcomas to be subtyped [3, 5, 6, 28]. Although by definition, a USTS has no reproducible immunophenotype, pattern of protein expression and no line of differentiation.

19.1.4 Genetics

Two different entities have been reported for URCS and USCS, both arising in children and young adults. There are those sarcomas with fusions of EWSR1 to non-ETS transcription factor genes such as SP3, PATZ1, POU5F1, SMARCA5 or NFATC2. These are often classified as URCS rather than an Ewing sarcoma [16]. However, there remains uncertainty whether these tumours represent a distinct entity or a variant of Ewing sarcoma.

There is another group of undifferentiated tumours with reported distinct genetic events. One involving CIC–DUX4 gene fusion resulting from a chromosomal translocation of t(4;19)(q35;q13) or t(10;19)(q26.3;q13). The second genetic abnormality involves a BCOR–CCNB3 gene fusion, as the result of an inversion of the X-chromosome. Studies suggest this may represent a distinct entity [35]. These tumours are clinically treated as an Ewing sarcoma. There have been a number of irreproducible chromosomal aberrations detected in URCS and USCS [1, 2, 21, 38, 39].

19.1.5 Imaging Findings

USTS is a histological diagnosis of exclusion and imaging appearances are non-specific [12].

Radiographs may be normal or reveal a non-specific soft tissue density, which is often greater than 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 19.2). Radiographs can detect periosteal reaction, cortical erosion and pathologic fracture [30]. Calcification or ossification can be detected in 5–20 % of patients [24, 27]. Calcifications within the tumour may be punctate or curvilinear. Peripheral heterotopic bone formation may be present and can mimic myositis ossificans.

Fig. 19.2

Radiograph of biopsy confirmed USCS. The radiograph demonstrates a bulging dense solid mass at the wrist

USTS on ultrasound is non-specific, but typically is a well-defined heterogeneous mass. Hyperechoic areas represent a cellular composition, and hypoechoic regions represent necrotic or haemorrhagic tissue (Fig. 19.3). USTS demonstrates increased Doppler signal (Fig. 19.4). Ultrasound is the modality of choice for image-guided biopsy and can be used to target suitable areas for biopsy, avoiding necrotic components and the feeding vessels.

Fig. 19.3

UPS of the thigh. Longitudinal panoramic ultrasound of a deep soft tissue mass in thigh demonstrates a heterogeneous solid mass with a hypoechoic centre. This represents haemorrhage/necrosis, which is frequently seen in USTSs. Ultrasound is the modality of choice for image-guided biopsy and can be used to target suitable areas for biopsy, avoiding haemorrhagic/necrotic components

Fig. 19.4

(a) and (b) transverse Doppler ultrasound of a solid thigh mass. The tumour in (a) and (b) demonstrates increased Doppler signal. Biopsy of the tumour in (a) confirmed a UPS and in (b) a USCS

On unenhanced CT, USTS is often a large, lobulated, soft tissue mass, hypo- to isodense to muscle. There are intralesional areas of low attenuation (myxoid, haemorrhage or necrosis). Solid portions of the USTS can demonstrate a diffuse heterogenous pattern or a nodular and peripheral pattern of enhancement post-contrast [7, 19] (Fig. 19.5). Fat attenuation is not observed in these tumours, and its presence is suggestive of a liposarcoma. CT may be used to evaluate the internal matrix and assess underlying bony structures for cortical erosion or periosteal reaction. Approximately 10 % of retroperitoneal lesions demonstrate calcification.

Fig. 19.5

Contrast-enhanced axial CT demonstrates a peripheral enhancing (black arrow) soft tissue mass with a non-enhancing necrotic centre (white arrow). Biopsy confirmed a UPS (Color figure online)

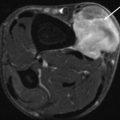

MRI provides the best assessment of the size and extent of the lesion and its relation to the adjacent bones, soft tissues and the neurovascular bundle. As with other modalities, the MRI features are non-specific. USTS is commonly intermediate to low intensity on T1-weighted images (WI) and intermediate to high on T2-WI [31] (Fig. 19.6). The signal intensity heterogeneity is related to the tumour components: fibrous tissue with high collagen content (low signal intensity on all pulse sequences), myxoid tissue (low signal intensity on T1 weighting and high signal intensity on T2 weighting) and haemorrhage (variable signal intensity with or without fluid-fluid levels) [20, 31] (Fig. 19.7). Tumours with extensive necrosis appear cystic. Calcification may present as foci of low signal on both T1-WI and T2-WI. Tumour margins are relatively well defined, often with a low signal intensity margin, representing a pseudocapsule. Aggressive tumours such as USTSs emphasises that the presence of a well-defined margin is a poor radiological indicator of malignancy. As with CT, solid components of USTS typically reveal nodular and peripheral enhancement (Fig. 19.6d, e).