CHAPTER 26 Vascular Injury and Parenchymal Changes

The spectrum of cerebrovascular trauma includes arterial occlusion, dissection, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, vasospasm, and venous thrombosis. Vascular trauma is the most common cause of stroke in individuals younger than 45 years of age1 and often has devastating consequences. Fortunately, newer diagnostic modalities such as CT angiography (CTA) have facilitated rapid diagnosis and treatment.

EXTRACRANIAL VASCULAR TRAUMA

Blunt Trauma

Epidemiology

Blunt injury to the carotid and vertebral arteries is reported in fewer than 1% of motor vehicle collisions.2 The injury may lead to disabling or lethal infarcts, especially in younger individuals. The true frequency of vascular injury is likely to be higher than reported, because 23% of patients with carotid or vertebral injury have no related symptoms at the time of presentation3 and the diagnosis is often overlooked in the presence of concurrent severe head injuries.

Clinical Presentation

Vertebral artery dissections may present acutely or first become evident hours to weeks later.4 Physical findings include neck hematoma, bruit, palpable thrill, and Horner’s syndrome.5 However, as many as 50% of patients with blunt carotid injury show no external evidence of neck trauma.6 Damage to the intimal surface of the vessel can lead to platelet aggregation and subsequent embolization, so antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs may be administered, provided there are no contraindications.2 Frank dissections and occlusions may lead to embolism/infarction of the brain stem, cerebellum, and posterior cerebral artery territory.

Pathophysiology

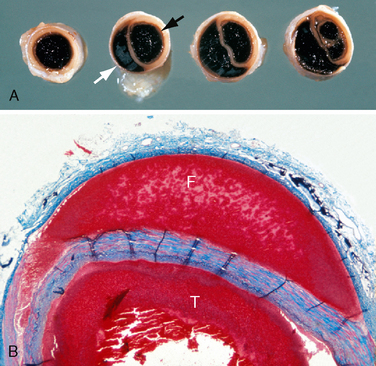

The internal carotid artery is vulnerable to intimal tearing, dissection, and subsequent occlusion as a result of rapid acceleration/deceleration of the head (Fig. 26-1). Intimal tears tend to occur where the internal carotid artery becomes stretched over the transverse processes of the upper cervical vertebrae or where the artery enters the skull base. Traumatic intimal tears may heal spontaneously or progress to dissection/occlusion.

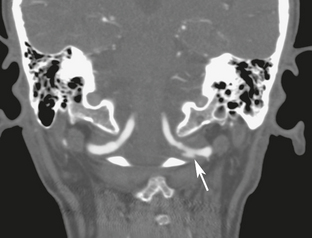

FIGURE 26-1 Autopsy specimens. Dissecting hematoma of the internal carotid artery. A, Gross specimen cut in cross section. Black arrow indicates the true lumen. White arrow indicates the false lumen. B, Histologic section. The plane of dissection advances between the media and the adventitia. (Masson trichrome stain). T, true lumen; F, false lumen.

(Courtesy of John Deck, MD.)

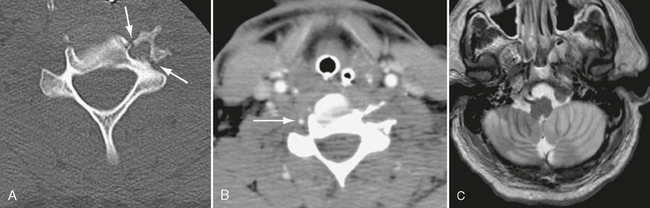

The long course of the vertebral artery through the foramen transversarium from C6 to C1 makes this vessel prone to traumatic dissection from motor vehicle accidents, sports injuries, and chiropractic neck manipulation. The C1-C2 articulation is the most mobile segment of the cervical spine, so C1-C2 is also the most common site of vertebral dissection. From C2 to C6, fracture-dislocation may injure the vertebral artery within the foramen transversarium, resulting in dissection or occlusion (Fig. 26-2).

FIGURE 26-2 A 39-year-old man presented with fracture-rotary subluxation at C6. A, Axial CT demonstrates fracture through the foramen transversarium of C6 (arrows). B, CTA shows occlusion of left vertebral artery at same level. Right vertebral artery is patent (arrow). C, T2W MR image demonstrates extensive cerebellar infarction, most likely due to anoxia, because it is bilateral.

Imaging

CT Angiography

Multidetector CT angiography (MDCTA) is highly accurate for detecting blunt cerebrovascular injury, with sensitivities of 97.7% and specificities of 100%.7,8 Therefore, MDCTA has replaced catheter angiography as a screening tool for blunt cerebrovascular injury at many level I trauma centers. Duplex ultrasonography, although accurate, cannot evaluate the carotid arteries at and above the skull base. Screening by MR angiography (MRA) presents logistical problems in the patient with multiple trauma, such as immediate MRI availability, lengthy examination time, patient motion, and incompatibility of many life support devices with MRI.

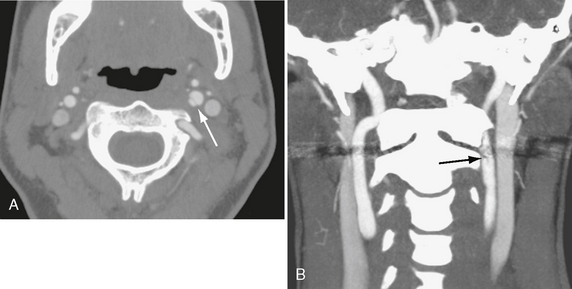

On contrast-enhanced CT, arterial injuries have varied appearances. With dissections, an intimal flap may be seen (Fig. 26-3), followed distally by tapering of the vessel. Maximum intensity pixel projection (MIPP) images confirm the abnormal morphology of the vessel lumen (Fig. 26-4). Pseudoaneurysms appear as collections of contrast material outside the wall of the injured artery (Fig. 26-5). Occlusions often present as a smoothly tapered artery that ends in a point. Thrombus may be seen as a filling defect within the artery (see Fig. 26-4C).

FIGURE 26-3 Traumatic internal carotid dissection in a 32-year-old woman. A, Axial CTA shows intimal flap (arrow). False lumen is on the medial side. B, Coronal MIP image. Arrow indicates flap.

FIGURE 26-4 Bilateral carotid dissection from a motor vehicle accident. A, Left internal carotid artery (white arrow) is markedly narrowed, as is right internal carotid artery (black arrow). B, Sagittal MIP image shows marked narrowing and irregularity of right carotid lumen (arrows). C, Higher slice shows thrombus (white arrow) in right petrous carotid and marked narrowing of left petrous carotid (black arrow).

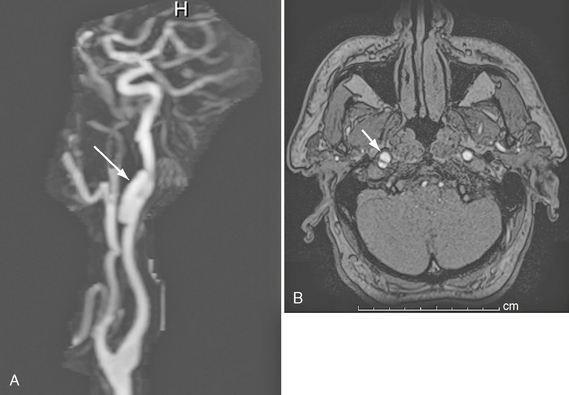

MR Angiography

Levy and associates showed that MRA has a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 99% for diagnosing carotid artery dissection.9 However, the sensitivity was only 20% and specificity 100% for diagnosing vertebral artery dissection. The best MRA indicator of dissection was an apparent increase in the external diameter of the artery (Fig. 26-6). Additional helpful MRI signs were narrowing of the luminal flow void and detection of intramural hematoma (Fig. 26-7).

FIGURE 26-6 Right internal carotid dissection in a 54-year-old man. A, Gadolinium-enhanced MRA. Arrow indicates pseudoaneurysm. B, Axial source image demonstrates true and false (arrow) lumina.

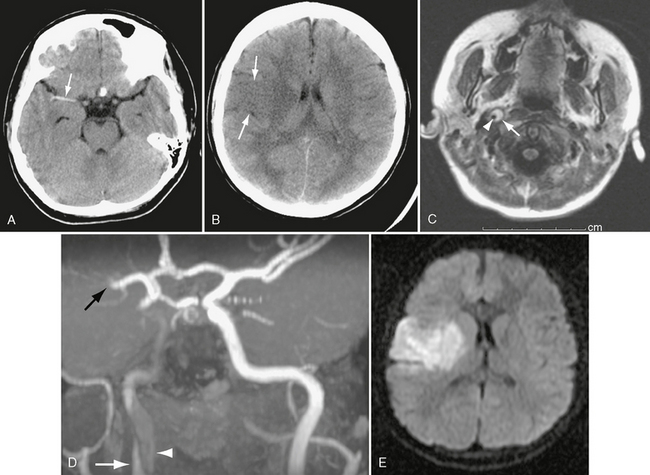

FIGURE 26-7 Right internal carotid dissection in a 12-year-old girl. A, Unenhanced CT shows dense right middle cerebral artery, consistent with thrombosis (arrow). B, CT a day later shows right frontal transcortical infarct (arrows). C, Axial FLAIR MR image on day 8 demonstrates intramural thrombus (arrow) surrounding lumen of internal carotid (arrowhead). D, Coronal oblique MRA shows clot in false lumen (white arrow), slow flow in true lumen (arrowhead), and occlusion of middle cerebral artery (black arrow). E, Diffusion-weighted MRI demonstrates extent of infarct.

Penetrating Trauma

Epidemiology

Injury to the great vessels of the neck is much more common with penetrating wounds than with blunt trauma, with an incidence approaching 25%.10 Gunshot and stab wounds are the most common mechanisms of penetrating injury. Blunt trauma and penetrating trauma cause similar lesions, including intimal flaps, dissection, occlusion, pseudoaneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula.

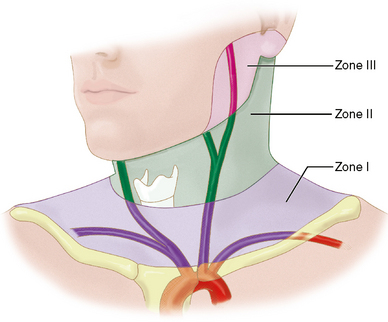

Clinical Presentation

For surgical purposes, penetrating neck wounds are divided into three zones, based on specific anatomic landmarks (Fig. 26-8). Zone I extends from the suprasternal notch to the cricoid cartilage. Zone II is the area from the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible. Zone III extends from the angle of the mandible to the skull base.11 Zone II injuries are the most amenable to surgical exploration, so surgery has been the preferred management of zone II injuries, until very recently, when feasible, endovascular therapies are increasingly replacing surgical exploration.

Imaging

CT Angiography

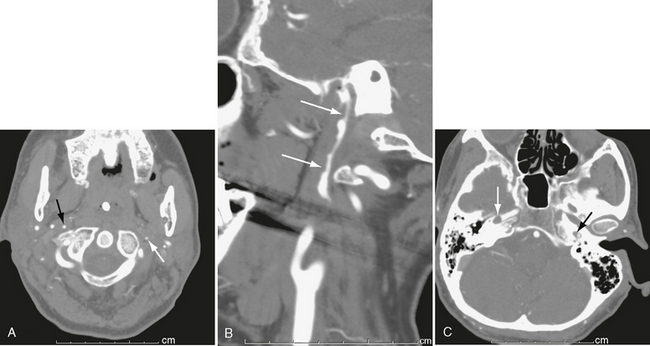

MDCTA provides information on the status of the vascular structures, the trajectory of the missile, the integrity of the aerodigestive tract and other soft tissues, and the osseous structures (Figs. 26-9 and 26-10). Patients who are hemodynamically unstable require surgical exploration, regardless of the entry zone. MDCTA data, however, may reduce the number of negative neck explorations of penetrating injuries.

FIGURE 26-9 Stab wound to left anterior neck in a 29-year-old man. A, Axial CTA demonstrates dissection flap in left common carotid (arrow). Arrowhead indicates air in soft tissues. B, Coronal MIP CTA shows small intimal flap (arrow) in common carotid artery.

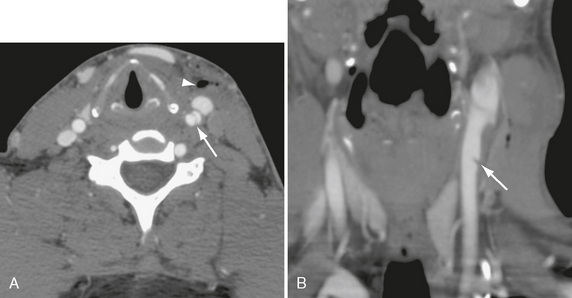

FIGURE 26-10 Gunshot wound with left vertebral occlusion. A, CTA shows shattered left C4 lamina (white arrow) and no flow in left vertebral artery (black arrow). B, Coronal CTA shows occlusion of left vertebral artery at C6 (arrow). C, Coronal MRA demonstrates no flow in cervical left vertebral artery. Note normal right vertebral artery (arrow). Left vertebral eventually reconstitutes at skull base (arrowhead).

INTRACRANIAL VASCULAR TRAUMA

Epidemiology

Intracranial arterial injuries most commonly result from penetrating trauma or fractures of the skull base. The artery most commonly injured is the internal carotid artery. This may be affected at its entrance to the carotid canal or at its exit from the cavernous sinus beneath the anterior clinoid process.12 Potential injuries include dissection, occlusion, pseudoaneurysm, and carotid-cavernous fistula.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation

Dissection

Intracranial carotid dissection may extend up the supraclinoid segment to the carotid bifurcation and then into the proximal anterior and middle cerebral arteries. This subintimal lesion causes significant luminal narrowing. It may lead to infarction and/or subarachnoid hemorrhage (see Fig. 26-7).

Fistula

A tear in the cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery can cause a high-flow arteriovenous communication between the artery and the cavernous sinus: a carotid-cavernous fistula. Such tears usually result from fracture of the sphenoid bone in the region of the sella turcica or the anterior clinoid process. Nontraumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas can develop from rupture of a cavernous-carotid aneurysm. The consequent increase in venous pressure and retrograde venous outflow through the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins can cause severe ipsilateral proptosis and chemosis, with a bruit that can be heard over the eye. Increased intraocular pressure and decreased retinal perfusion may cause vision loss.

Pseudoaneurysm

When injury disrupts all three layers of an arterial wall the resulting hemorrhage may become contained by the surrounding soft tissue. The blood within the hematoma remains in contact with turbulent flow in the parent artery.5 With time, the wall of the hematoma organizes, becomes lined with fibrous tissue, and forms a pseudocapsule around the pseudoaneurysm. Pseudoaneurysms are unstable lesions that can rupture and present as sudden intracranial hemorrhage. They often rupture at 2 to 8 weeks after the traumatic event (Fig. 26-11) but may not rupture until years after the injury. Mortality after pseudoaneurysm rupture is 30% to 40%.13 Treatment usually consists of occlusion of the lumen with detachable coils or trapping of the parent artery. Covered stents are a promising future alternative.

Imaging

Dissection

On conventional angiography or CTA the dissected segment is narrowed and irregular, sometimes tapering to occlusion. There may be intraluminal thrombus and/or pseudoaneurysm. MRI and MRA are also quite useful for demonstrating dissection. On T1-weighted (T1W) imaging, hemorrhage in the wall of the artery is frequently seen as increased signal intensity outside the narrowed lumen (subacute blood) (see Fig. 26-7C).

Fistula

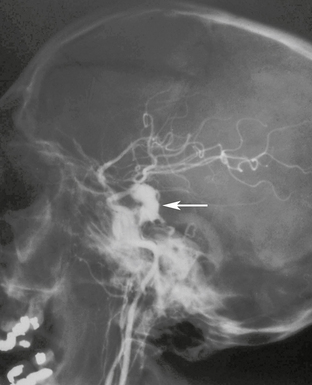

In patients with carotid-cavernous fistula, contrast-enhanced CT may show dilatation of the ipsilateral superior ophthalmic vein (>4 mm), outward convexity of the cavernous sinus, engorgement of the extraocular muscles, proptosis, and preseptal soft tissue swelling. CTA may demonstrate irregularity of the cavernous carotid artery (Fig. 26-12). If the fistula has very high flow, CTA may also show involvement of both orbits. MRI and MRA more clearly depict the patterns of venous outflow, including the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses, emissary veins to the pterygoid plexus, and sphenoparietal sinuses. Despite the recent advances in noninvasive imaging, catheter angiography with rapid filming rates is still required to demonstrate the location and size of the fistula definitively (see Fig. 26-12D) and to plan interventional therapy. Currently, the treatment of choice is transarterial occlusion of the fistula with detachable balloons. Advances in covered stent technology may allow for bridging the tear in the carotid artery while preserving vessel patency.14,15

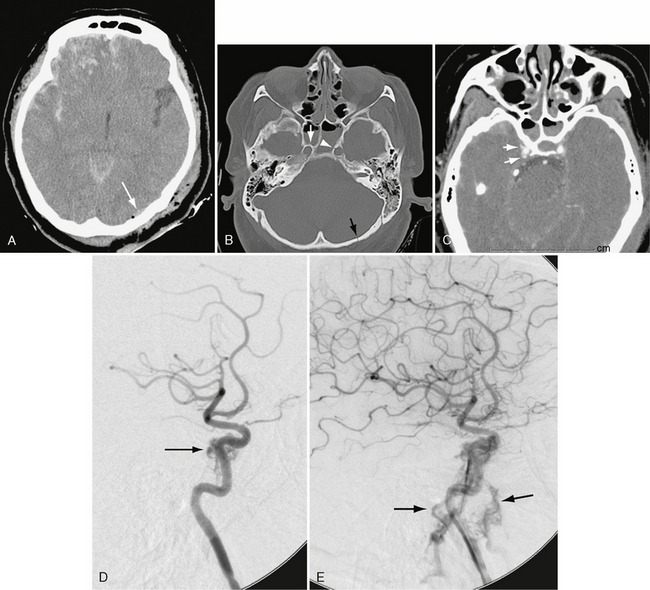

FIGURE 26-12 Traumatic carotid-cavernous sinus fistula in a 45-year-old woman. A, Unenhanced CT demonstrates extensive right frontal hemorrhagic contusion and a small left occipital epidural hematoma (arrow) with air. B, Bone window CT demonstrates right (white arrow) and left (arrowhead) carotid canal fractures and left occipital fracture (black arrow). C, CTA shows indistinctness of right cavernous carotid and early opacification of cavernous sinus (arrows). D, Lateral right carotid angiogram, early arterial phase, shows early opacification of cavernous sinus (arrow). E, Later image shows filling of inferior petrosal sinuses during arterial phase (arrows).

ACUTE PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGES IN TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

The normal adult ICP is 0 to 15 mm Hg. The adult intracranial volume is approximately 1500 mL. Intracranial compliance is defined as the change in intracranial volume divided by the change in ICP.16 Treatment of head injury is based on how the treatment affects ICP and compliance.16

Cerebral perfusion pressure is the difference between the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the intracranial pressure (ICP): CPP = MAP − ICP. Stated differently, CPP is the net pressure at which blood perfuses the brain. In a healthy individual with a normal MAP of 50 to 150 mm Hg, CBF is held constant through autoregulation by brain arterioles. When MAP falls below 50 mm Hg, compensatory mechanisms are no longer adequate. The CBF decreases, and ischemic injury is possible. Conversely, when MAP exceeds 160 mm Hg, excessive CBF may occur and lead to increased ICP. Autoregulation works well in the noninjured brain but is often impaired in the traumatized brain,16 so ICP rises with intracranial injury. The brain has very limited tolerance for increases in ICP, especially rapid increases. Uncontrollable rise in ICP is the single most frequent cause of death in traumatic brain injury. The elevated ICP poses two dangers. First, increased ICP can lead to decreased CPP and ischemic infarction; indeed, 80% to 90% of patients who die of traumatic brain injury have evidence of ischemic injury at autopsy.17 Second, very elevated ICP can lead to brain herniation.

CEREBRAL EDEMA

Cerebral edema is an increase in brain tissue volume resulting from an increase in tissue water content.18 It may be focal or diffuse.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of brain swelling after traumatic brain injury is unclear. Conventional wisdom held that vascular engorgement caused an increase in CBV that then elevated the ICP. However, the vascular engorgement “etiology” has not been substantiated in animal studies.19 Until recently it had not been possible to measure brain water content or CBV in the living brain-injured patient. Brain tissue water content can now be calculated using phase-sensitive inversion recovery slices, from which a pure T1W image can be calculated.20,21 The calculated T1W image is then converted into a brain water image. CBV is measured using a combination of stable xenon CT and contrast-enhanced CT.22 The xenon CT scan is used to obtain CBF. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT is used to determine mean transit time. CBV is then calculated from these two parameters using the equation: CBV = mean transit time × CBF.

Marmarou and colleagues studied 31 patients with severe traumatic brain injury who had determinations of both brain tissue water and CBV. They found that brain water was increased but CBV was actually decreased.23 They concluded that the brain swelling associated with traumatic brain injury is caused by brain edema not increased CBV. An increase of only 1% in brain water content causes an increase in brain volume of 4.4%, which can elevate the ICP above 20 mm Hg.24

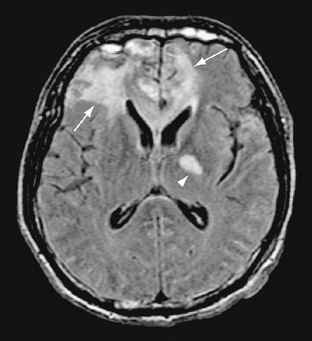

Imaging

The cerebral edema associated with severe traumatic brain injury is both intracellular (cytotoxic edema) and extracellular (vasogenic edema) (Fig. 26-13). MRI study of patients with diffuse brain injury showed restricted diffusion and decreased ADC values, indicating intracellular edema.24 The CBF values of the study patients were all well above the ischemic threshold, eliminating ischemia as the cause of restricted diffusion.24 Alternatively, in a case with focal brain injury, the core of a contusion and the area immediately surrounding it showed increased apparent diffusion coefficient, indicating vasogenic edema (Fig. 26-14). The brain more distant from the contusion showed decreased apparent diffusion coefficient, indicating cytotoxic edema. Thus, the cerebral edema seen in traumatic brain injury is both intracellular and extracellular, with cytotoxic edema predominating.

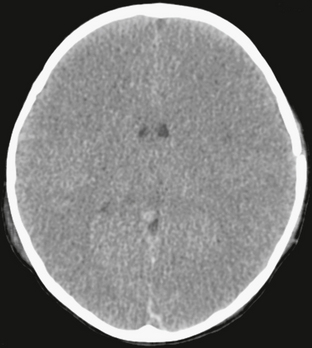

FIGURE 26-13 Diffuse cerebral edema after closed-head injury in a 2-year-old boy. Unenhanced CT shows loss of gray matter/white matter discrimination, as well as small ventricles.

FIGURE 26-14 Severe frontal contusions in a 36-year-old man. FLAIR MR image demonstrates vasogenic edema surrounding contusions (arrows). A diffuse axonal injury is seen in the left internal capsule (arrowhead).

The mechanism by which the cytotoxic edema forms remains unknown but may be related to mitochondrial dysfunction.24 The cellular edema develops slowly and becomes dominant at 1 or 2 weeks after injury.25 The vasogenic edema is thought to result from breakdown in the blood-brain barrier immediately after traumatic brain injury. It predominates in the first hour or so after injury. Animal studies show that the blood-brain barrier is usually reestablished within 30 minutes after the trauma.25 The type of edema present in traumatized brains therefore also varies with the time after injury.

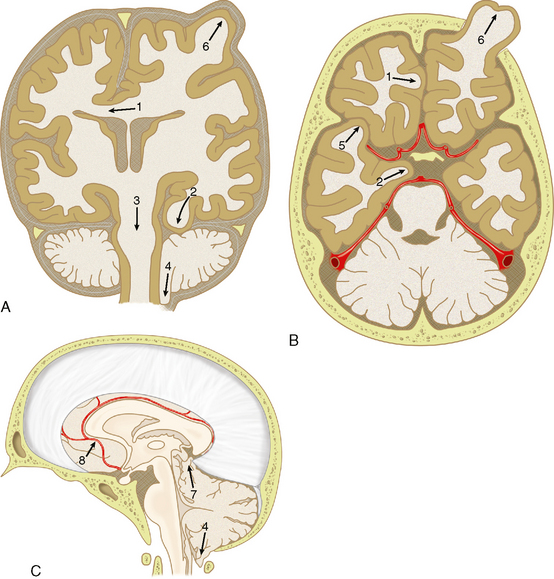

ACQUIRED CEREBRAL HERNIATIONS

Herniation is displacement of brain tissue from one compartment into another. It is a dreaded complication of mass effect, regardless of the cause, because it may result in infarction, coma, or death. The major types of brain herniation include subfalcine, transtentorial, and tonsillar (Fig. 26-15). Transtentorial herniation is subdivided into lateral (uncal, hippocampal) and central types and then described as descending or ascending in accordance with the direction of brain shift. Most central transtentorial herniation is directed inferiorly, but significant ascending central herniation can result from masses situated inferior to the tentorium. Herniations are readily detected by both CT and MRI and must be recognized to prevent or limit serious neurologic sequelae (Table 26-1).

FIGURE 26-15 Patterns of cerebral herniation. A, Coronal. B, Axial. C, Sagittal representations of the skull, dural portions, and brain. 1, Subfalcine; 2, uncal; 3, descending transtentorial; 4, tonsillar; 5, transalar; 6, external; 7, ascending transtentorial; 8, anterior cerebral artery branches (pericallosal and callosomarginal arteries. Vascular structures are shown in red.

(From Johnson PL, Eckard DA, Chason DP, et al. Imaging of acquired cerebral herniations. Neuroimag Clin North Am 2002; 12:217-228.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree